Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF), which occurs due to abnormal transport of sodium, chloride, and bicarbonate across epithelial cells, is a multisystemic disorder. The CFTR gene has been found to include over 1,000 mutations that cause CF, with ΔF508 being one of the most severe and common variants. CFTR dysfunction causes mucus retention, persistent infection, and ultimately local airway inflammation, which is detrimental to the lungs. CF is characterised by chronic pulmonary infection and inflammation, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, and gallstones, and might include several comorbidities such as CF-related diabetes or CF-associated hepatobiliary disease. Diagnosis of this autosomal recessive condition can be done as part of newborn screening, or recognition of the documented multiorgan clinical symptoms may also lead to diagnosis. People with CF now have a longer life expectancy thanks to management techniques like increasing mucociliary clearance, bronchodilators, recombinant DNase, and CFTR modulators. With the rise in survival rates and the number of individuals with CF, clinical trial institutes are actively investigating a wide range of alternative strategies, which will become increasingly necessary.

Key Points

1. A recent study indicates that 105,352 individuals across 94 countries have been diagnosed with cystic fibrosis globally, with patient registries accounting for 90% of this population.2. This study aims to examine the evolving dynamics of long-term disease management, encompassing mental health and multisystemic comorbidities, against the context of increasing survival rates and innovative therapeutics.

3. Subsequent to the endorsement of CFTR modulators in 2019, the median survival age markedly increased from 48.5 to 68.0 years during a 5-year span.

INTRODUCTION

Two mutated alleles of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene result in the autosomal recessive hereditary illness known as cystic fibrosis (CF), where the CFTR protein is either absent or deficient. The trans-epithelial passage of the chloride ion via the channel is prevented when the CFTR protein is not functioning.1 Symptoms include dehydration of secretions, intraductal obstruction, inflammation, fibrosis, and ultimately damage to specific organs due to aberrant CFTR protein, which inhibits the production of water, chloride, and other ions.2 Due to a lack of knowledge and difficulty in accessing diagnostic resources, CF is not recognised at many outlying centres. Recent developments in disease treatment, such as multifaceted symptomatic CF care, systematic neonatal screening, and more recently, highly effective CFTR modulators, have had a notable impact on the prognosis of individuals with CF over the past few years. Following their approval in 2019, the median survival age rose significantly from 48.5 to 68 years over a 5-year period.3

In this age, the significance of a review on CF lies in its ability to bridge critical gaps in global understanding. As a condition, it has a much wider prevalence than historically anticipated, thanks in part to improved national data and diagnostic tools. This necessitates a comprehensive understanding of its pathophysiology and clinical management. Clinically, it educates healthcare providers in recognising CF in populations where it is often misdiagnosed, while socially, it advocates for equitable care and policy reform. This review seeks to address the ever-shifting landscape of long-term management of the disease, including mental health and multisystemic comorbidities, amidst the backdrop of improving survival rates and groundbreaking therapies.

METHODOLOGY

The authors conducted an electronic search using various databases, including Medline through Ovid, PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, and Google Scholar, for studies related to the authors’ study that were published after 1st January 2016. The goal was to find articles related to keywords such as “Cystic Fibrosis (CF)”, “CFTR,” and “Mutation,” in conjunction with “Prevalence,” “Diagnosis,” “Pathophysiology,” and “Therapeutic Measures.” This search focused solely on studies involving humans, without any language restrictions. Moreover, the authors manually checked reference lists from relevant studies to see how the information applied to their review and considered 43 papers for this research study. To prevent overlap in patient groups, if authors wrote about the same cohorts in multiple publications, the authors only included the most recent or detailed study in their analysis. To minimise bias during data abstraction, four reviewers independently gathered the required data.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The disease was initially thought to affect only White people, but there is growing awareness that CF is more prevalent than previously thought in other ethnic groups, such as Asian, African, and Hispanic populations.4 The majority of the data that are now available come from national registries, which are present in numerous nations, but vary in their level of comprehensiveness.5 A new study estimates that 105,352 people from 94 countries have received a diagnosis of CF worldwide, with patient registries identifying 90% of this population.6 More than 50,000 individuals with CF from 38 European nations provided data to the European Cystic Fibrosis Patient Registry (ECFSPR) in 2019. In contrast, 33,989 patients with CF were listed in the United States Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry (USCFFPR) in 2024.7 For many years, only North America, Western Europe, and Australia-New Zealand have had data on the epidemiologic state of CF. It has become clear during the last 10 years that CF is also common in other parts of the world, such as Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and Eastern Europe.6

MOLECULAR GENETICS

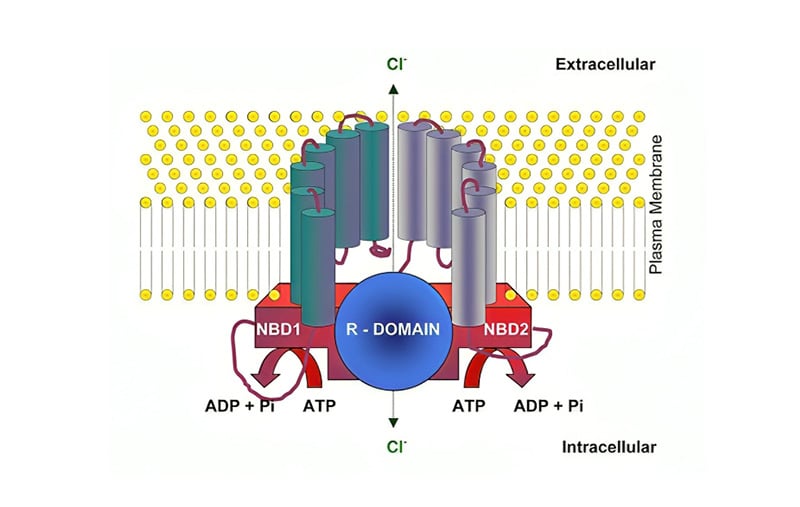

Chromosome 7q31.2 contains the CFTR gene, which codes for the CFTR protein, belonging to the family of membrane transporters known as adenine-binding cassette transporters, or transport ATPases. Two transmembrane domains (each with six α-helices), two cytoplasmic nucleotide binding domains, and a regulatory domain (R domain) that houses protein kinase A and C phosphorylation sites are all present in the 1,480-amino acid polypeptide CFTR. Figure 1 displays the typical CFTR protein.8 The regulatory domain’s cAMP-dependent phosphorylation is controlled by protein kinase A. The chloride channel opens as a result of ATP binding, causing the nucleotide binding domains to dimerise. The dimer is broken, and channel closure is started by ATP hydrolysis.9

Figure 1: CFTR structure.

ADP: adenosine diphosphate; NBD: nucleotide-binding domain; Pi: inorganic phosphate.

Adapted from UK Respiratory Gene Therapy Consortium.8

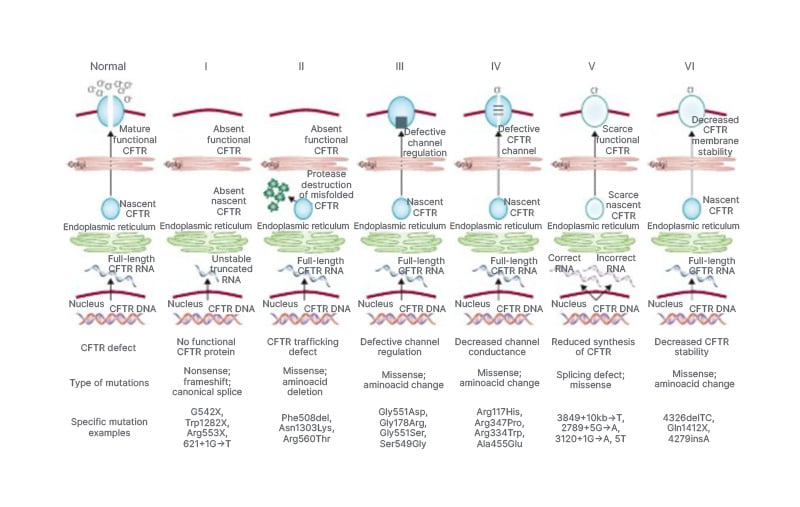

CFTR is a bicarbonate channel as well as an ATP-gated chloride channel. Furthermore, it has been proposed that CF-like disease could result from an accumulation of mutations in the CFTR gene and the gene encoding the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC).10 The level of CFTR content and function is influenced by the particular genetic mutation type, which in turn influences the severity of the disease. Based on their effects on the function of the protein, six types of CFTR mutations have been discovered. Figure 2 illustrates the types of CFTR mutations.5 The deletion of phenylalanine at position 508 (ΔF508) in the CFTR protein is one of the most severe, common, and significant mutations in all populations.11

Figure 2: Classes of CFTR mutations.

Adapted from Bell SC et al.5

Generally speaking, pancreatic insufficiency and increased rates of pulmonary infections are linked to mutations of Classes 1–3 (classified as severe mutations) that result in a total or nearly total lack of CFTR function. On the other hand, modest mutations of Classes 4–6 are associated with better nutritional status and less severe lung disease, and they are also likely to have greater residual CFTR function.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In their natural state, the epithelial tissues affected in CF perform distinct roles. Some, like those in the airways and distal intestinal epithelium, are volume-absorbing, where fluid balance is maintained through the absorption of sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻), with water following via the ENaC. Others, like the sweat duct epithelium, are salt-absorbing but not volume-absorbing, where CFTR mediates Cl⁻ absorption, which in turn enables Na⁺ absorption via ENaC, without accompanying water reabsorption. In CF, CFTR dysfunction disrupts these processes. In volume-absorbing epithelia, this leads to dehydration of the airway surface liquid, resulting in viscous mucus that adheres to the epithelium. This promotes bacterial colonisation and infection, which triggers inflammation. The inflammatory response further increases mucus production and obstruction, establishing a vicious cycle of infection, inflammation, and mucus plugging.

Lung

The primary theory of airway pathology is that the airway surfaces are ‘dehydrated’ due to improper regulation of Na⁺ absorption and an inability to release Cl⁻ via CFTR.12 Mucus adheres to the airway surface because of both thickening and periciliary liquid depletion; hence, both ciliary and airflow-dependent (cough) processes fail to remove mucus. CF airways are characterised by infections that affect the mucus layer instead of the airway wall or epithelium. Failure to remove mucus is consistent with the airways of people with CF being more susceptible to long-term infections by Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.13 Recent research indicates that the mucus of people with CF has extremely low O₂ tension.14 The tendency of Pseudomonas species to form biofilm colonies inside mucus plaques adhering to CF airway surfaces may be influenced by both mucus hypoxia and mucus stasis.15,16

The inflammatory process is also influenced by a protease-antiprotease imbalance created even in the absence of organisms.17 The prolonged presence of inflammation causes the release of proteases from the neutrophil and bacteria, if present. The common serine proteases include elastase, cathepsin G, proteinase III, collagenase, gelatinase, and plasminogen activator. These, along with bacterial proteases, cause structural damage, impair ciliary damage, and reduce immunity. The antiprotease production is normal but is outnumbered by proteases and is also inactivated in the presence of bacterial protease.

Pancreas

The secretion of bicarbonate and Na⁺ ions into the pancreatic ducts via an apical chloride-bicarbonate exchanger is impaired in CF, primarily due to mutations in the CFTR chloride channel. Dysfunctional or absent CFTR leads to the production of thick, dehydrated secretions, causing enzyme retention and progressive destruction of pancreatic tissue.18 This mechanism is responsible for pancreatic insufficiency, which commonly affects individuals with Class I, II, III, and VI CFTR mutations, mutations that result in little to no functional CFTR protein. In contrast, individuals with Class IV and V mutations retain partial CFTR function. This allows for more effective ion and fluid secretion, reducing the risk of ductal obstruction and preserving exocrine pancreatic function. These individuals are considered pancreatic sufficient and typically experience milder gastrointestinal symptoms. However, even pancreatic sufficient individuals remain at risk for progressive pancreatic deterioration over time, underscoring the need for ongoing monitoring.

Intestine

The intestinal epithelium is unable to clear off produced mucins and other products from intestinal crypts due to defective Cl⁻ and water secretion. Excessive liquid absorption, which reflects anomalies in CFTR-regulated Na⁺ absorption, may worsen the reduced CFTR-mediated secretion of liquid. Dysfunctions lead to the desiccation of intraluminal contents and obstruction of both the small and large intestines.19

Hepatobiliary

Bile duct proliferation, localised biliary cirrhosis, and thicker biliary secretions are all consequences of defective hepatic ductal salt (Cl⁻) and water secretion. Cholelithiasis and chronic cholecystitis can result from the CF gallbladder epithelium’s incapacity to produce water and salt.20 The European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) recommend the use of the term CF hepatobiliary involvement (CFHBI) to refer to “all liver and biliary tract-related signs, clinical and/or biochemical diagnostic findings” in patients with CF. The proposed CFHBI classification is based on:21

- Elevation in liver enzymes (AST/ALT/GGT 1.5-times the upper limit of normal)

- Liver imaging

- Histopathology of the liver

- Stiffness of the liver

- Portal hypertension

- Biliary manifestations

- Malignancies of the liver and biliary tract

Patients with evidence of liver disease are categorised as having either advanced CF-associated liver disease (CFLD) or CFHBI. Any patients with CF having evidence of cirrhosis with or without portal hypertension are defined as having advanced CFLD. The European criteria were outlined by Debray et al.22 in 2011, which suggests that the diagnosis of CFLD should be taken into consideration if at least two of the four categories (liver function tests, ultrasound, liver biopsy, and physical examination) show significant abnormalities.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATION

Though most individuals with CF come to the doctor with respiratory and gastrointestinal complaints along with malnutrition, respiratory symptoms are still observed in most cases of CF.23,24 Patients with respiratory system involvement often present with airway obstruction, bronchiectasis, pneumothorax, or haemoptysis. Other than the previously stated clinical conditions, patients do come with distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS), insulin-dependent diabetes, gallstones, and acute salt depletion.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

The following simplifies the diagnosis of CF in suspected individuals.25

- ANY ONE OF

- One or more of distinctive phenotypic traits, OR

- A history of CF in a sibling, OR

- A positive newborn screening test result

- AND ANY ONE OF

- An elevated concentration of Cl⁻ in sweat on ≥2 instances, OR

- Presence of 2 CFTR mutations, OR

- Demonstration of irregular epithelial ion transport

INVESTIGATIONS

Testing for Carrier

Testing for the presence of the abnormal gene associated with CF can be advantageous under specific circumstances. This includes situations where an individual has a family member who is a confirmed carrier of the gene, such as a parent, sibling, or child. Additionally, if an individual has a close relative diagnosed with CF, testing may provide valuable insights. Furthermore, if an individual’s spouse is known to carry the CF gene, undergoing genetic testing can facilitate informed decision-making regarding family planning and health management. A blood test or, occasionally, a specific mouthwash can be used to obtain a sample of cells for this kind of genetic testing. After that, the sample is sent to a lab to be examined for the defective gene. A person is considered a carrier of CF when they inherit a normal CFTR gene from one parent and a pathogenic variant CFTR gene from the other. Although they are usually healthy, CF carriers might pass on the mutated CFTR gene to their offspring. In order to identify potential carriers of CF, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommended a panel of 23 core mutations (including ΔF508, G551D, R553X, and 1717-G>A) that will help in diagnosing 49–98% of carriers depending on ethnicity (Ashkenazi Jewish, Caucasian, Hispanic American, African American, and Asian American).26 The ACMG panel includes known CF-causing mutations with an allele frequency of ≥0.1% in patients with CF. Additional testing should be done to confirm the diagnosis following a positive screening test.

Prenatal Screening

Chromosomal abnormalities can be detected via amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling. Amniocentesis between 15–20 weeks and chorionic villus sampling between 10–13 weeks can be performed to detect CFTR variants.27

Newborn Screening

A medical practitioner will prick the baby’s heel when they are 2–3 days old and gather blood droplets on a Guthrie card or the blood spot card. After that, the blood is transported to a lab to be examined for anomalies that might point to CF. By the time the child is 6–8 weeks old, the results should be available. The immunoreactive trypsinogen test is used for screening. All current newborn screening procedures primarily utilise functional detection of immunoreactive trypsinogen, a pancreatic exocrine biomarker elevated in the bloodstream of the majority of patients with either partial or nonfunctional CFTR mutations.228 Although it is an early screening test, the diagnosis should be confirmed by additional testing.

Though the above-mentioned procedure can be performed to confirm the diagnosis of CF, the pilocarpine sweat test is still considered the gold standard test for diagnosis. Sweat test is generally considered after a positive newborn screening test and performed as soon as 72 hours after birth.29 These infants, with a presumptive diagnosis, should undergo a repeat sweat test after 2–4 weeks of treatment.29 Possible results obtained from the sweat test can be classified into three groups: diagnostic, borderline, and unlikely.24 CF is diagnosed when sweat Cl⁻ concentration is more than 60 mmol/L, and the test should be repeated when sweat concentration is between 30–59 mmol/L.

Nasal Potential Difference Test

To evaluate the intake or secretion of Na⁺ and Cl⁻, the assay essentially entails dripping tiny amounts of the test solutions into the anterior nostril.

Other tests, including X-ray of the chest, ultrasound of the abdomen, spirometry, sputum cultures, and CT and MRI of the chest, abdomen, and sinuses can all support the diagnosis of CF.

COMPLICATIONS

Pulmonary Complications

Pneumothorax

Though in recent years the number of pneumothorax occurring due to CF has decreased, a study estimated pneumothorax to occur in one in 167 patients suffering from CF every year.30 Infection with P. aeruginosa or Burkholderia cepacia, a projected FEV₁ of less than 30%, a history of severe haemoptysis, and Aspergillus colonisation are risk factors for pneumothorax.

Pulmonary exacerbation

Common signs and symptoms suggesting pulmonary exacerbation in patients with CF are increased cough, voluminous cough, appetite loss, weight loss, and respiratory rate changes.31 Mild pulmonary exacerbation tends to present as a precursor of severe exacerbation, and studies suggest that early aggressive treatment improves disease outcome in the long run.32,33

Haemoptysis

Haemoptysis related to CF is usually associated with chronic inflammation and can also present as a part of pulmonary exacerbation, presenting in 3% of patients with CF each year.34-36 Romàn et al.37 found that 31 out of 132 patients with CF did experience haemoptysis.

Non-Pulmonary Complications

Distal intestinal obstruction syndrome

DIOS is the most common complication of CF and occurs due to stagnation of viscous faecal material in the bowel lumen along with thick mucus, which gets adherent to the distal ileum.38,39 Patients with DIOS often present with abdominal mass, pain in the right lower quadrant, distension, and vomiting.39 Patients with CF with genotypes associated with severe loss of function variants usually present with DIOS.40

Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes

The pancreas gets damaged by CF because of its thick secretions, which cause fatty infiltration and islet cell remodelling, ultimately leading to diabetes.41 Usually identified in individuals with pancreatic insufficiency, CFRD has been linked to higher morbidity and mortality rates due to poorer pulmonary function and nutritional condition.42 Since CFRD is frequently asymptomatic, latent CFRD may be the cause of unexpected declines in weight, growth, or lung function.43

Gallstones

Gallstones are commonly found in patients with CF.44 For a long time, it was believed that patients with CF had cholesterol stones, but over time, it was discovered that black pigmented stones were more frequently observed than cholesterol stones.20,45 In fact, it is believed that aberrant bile acidification, a mechanistic flaw caused by the absence of CFTR in the biliary epithelium itself, is the cause of black, distinctly coloured stones.

Psychological symptoms

TIDES, a multinational psychological screening study conducted across nine countries, showed that depression and anxiety are 2–3 times more prevalent in patients with CF, and recommended annual screening for psychological symptoms.46 There is growing apprehension regarding the incidence of anxiety, procedural-related anxiety/trauma, depression, and behavioural difficulties among children with CF, and their effects on health and health behaviours.47 The influence of social deprivation, food poverty, and family dynamics on health outcomes is evident early in life with CF, underscoring childhood as a pivotal phase where psychosocial interventions could enhance future health trajectories.48 Therefore, when a caregiver notices clinically heightened symptoms of anxiety among children aged 7–10 years, a clinical evaluation is advised.34 Depressive symptoms are common in adults with CF and correlate with diminished health-related quality of life.49

Osteoporosis

Low bone density and a higher risk of fractures are features of CF-associated bone disease, another consequence of CF. The persistent inflammatory condition of these individuals, along with episodes of infectious exacerbations, stimulates osteoclastogenesis and results in bone resorption.50 In addition to inadequate dietary status, malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin D and K is probably the cause of poor bone health.

MANAGEMENT

CF affects multiple organs, thereby making its treatment difficult. A comprehensive multidisciplinary treatment team is, therefore, beneficial to diagnose the complications of the disease early and provide proper treatment so as to improve quality of life. The team should consist of paediatricians or adult physicians, nurses, dieticians, physiotherapists, clinical psychologists, and social workers, coordinated by a specialist physician.51 Patients with CF should preferably be treated in a regional ‘cystic fibrosis centre’ equipped with such a multidisciplinary team.52 Current guidelines recommend centre-based treatment, as this has been shown to have improved life expectancy and better health outcomes.53-55 Up until very recently, the treatment was primarily symptomatic, correcting the anomalies as a result of the loss of function of CFTR. But before treating, we also need to prevent the pulmonary infections that cause the exacerbations. Prevention of pulmonary exacerbation is the most practical application of preventive therapy, which prevents decline in lung function, decline in quality of life, hospitalisations, and decreased survival.30 Multiple strategies are employed to attain this objective, including enhancing nutrition and managing diabetes effectively.30 Inhaled colistin combined with oral ciprofloxacin has effectively prevented P. aeruginosa infections, a well-documented infection among patients with CF.56 Routine bronchoscopy may be performed to acquire airway cultures, facilitating early diagnosis and preventing potential infection dissemination, if applicable.

Pulmonary

Mucolytics

Both hypertonic saline 3% or 7% and mannitol as a dry powder by metered-dose inhaler have been shown to enhance mucociliary clearance.57,58

Bronchodilators

These are used to reduce the narrowing of bronchioles. Despite the widespread and regular use of short-acting inhaled bronchodilators in patients with CF, there is no strong evidence to support such use. Nevertheless, they are often given before airway clearance to open the airways and allow better expectoration of mucus.59

Inhaled corticosteroids

Corticosteroids in CF are used to improve lung function and quality of life, and reduce pulmonary exacerbations. Multiple studies have failed to demonstrate any statistical or clinical benefits of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) use in CF.60 The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) currently discourages the regular use in patients ≥6 years of age without asthma or allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.61 Use of ICS poses a theoretical risk of growth impairment. A retrospective study conducted by Balfour-Lynn et al.62 revealed that ICS therapy was linked with a significant reduction in the lung function decline but decreased linear growth.62,63 A review by Sheikh et al.,64 however, failed to demonstrate any substantial benefit and concluded that the risks related to use of inhaled CS exceed the benefits.

Antibiotics

Since persistent infection and inflammation are key factors in the course of lung illness, studies have shown that people with CF benefit from the prudent use of antibiotics.65 Common antibiotics used in patients with CF are amoxicillin, dicloxacillin, cephalexin, flucloxacillin, co-trimoxazole, vancomycin, linezolid, and rifampin.65,66

Airway clearance techniques

This includes interventions like:56

- Conventional chest physiotherapy (postural drainage, percussion, and vibration)

- Positive expiratory pressure (10–25 cm of H₂O) or high-pressure positive expiratory pressure therapy (40–140 cm of H₂O)

- Autogenic drainage

- Airway oscillating devices

- Active Cycle Breathing Technique67

Dietary and Nutritional Advice

A systematic review by Thornton et al.68 found dietary intake of adult patients with CF to be less than optimal. The 2021 updated European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism – European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition – European Cystic Fibrosis Society (ESPEN-ESPGHAN-ECFS) guidelines recognise a shift from high-fat diet to healthy eating, attributed to the new class of highly effective drugs, CFTR modulators:69

- Fat-soluble vitamin supplementation

- Oral nutritional supplements for patients who fail to achieve optimal nutritional status with dietary intake and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy

- Trace elements

- a) Calcium (assessed annually, at least)

- b) Zinc, for those with proven or at risk of deficiency

- c) Iron, to be given for deficiency persisting even after resolution of underlying inflammation

- d) Fractional excretion of sodium, to be used for determining the need for sodium supplementation

- No recommendations are made pertaining to glutathione, essential fatty acid and the use of appetite stimulants.

Molecular Therapy

Recombinant DNase

The purified form of recombinant DNase present natively in humans is produced industrially through bacterial synthesis and administered in humans through inhalation route. Dornase alfa, which is a recombinant DNase, reduces mucous viscosity in the respiratory tract and helps in mucous clearance.70-72 DNase is currently the only mucus-degrading drug that has been shown to be effective in CF, and it is frequently used in combination with conventional medications to treat and control CF.73

CFTR Modulators

Ivacaftor is a potentiator that was the first CFTR modulator to be sold commercially. Research on individuals with Class III gating mutations showed notable improvements in weight, sweat chloride, occurrence of exacerbations, and FEV1.74 A corrector called lumacaftor was created to help cure CFTR misfolding caused by Class II mutations, such as F508del, the most prevalent CFTR mutation.75 However, in patients homozygous for the F508del mutation, lumacaftor/ivacaftor combo has been demonstrated to benefit lung function and exacerbations.76 In 2019, a new corrector called tezacaftor was authorised for use in conjunction with ivacaftor in patients who had at least one of 26 additional mutations and F508del homozygotes. Alyftrek (vanzacaftor/tezacaftor/deutivacaftor) has been approved by the US FDA in 2024 for use in patients aged more than 6 years and having at least one F508del mutation.77

Treatment for Associated Problems

Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy is administered in capsule form to aid digestion.78 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen, are utilised to reduce inflammation. Proton pump inhibitors are prescribed to diminish acid secretion, thereby enhancing the efficacy of pancreatic enzymes. Enemas may be employed to manage gastrointestinal obstructions, while stool softeners are recommended to prevent bowel obstructions. Insulin therapy is essential for managing CFRD, and bisphosphonates are indicated for the treatment of osteoporosis. Routine vaccinations are crucial in preventing superinfections.79 Psychological interventions like cognitive behavioural therapy, motivational interviewing, and counselling are reported to be effective in helping patients cope with the disease, improve adherence to therapy, and improve their quality of life.80

RECENT UPDATES

In 16 different countries, a European study known as HIT-Cystic Fibrosis is currently underway.81 By examining the mini-guts (organoids) of patients with (ultra)-rare mutations in vitro, the initiative aims to predict clinical treatment response and provide modulator medicines to these patients.81

The forskolin-induced swelling assay is a preclinical functional assay on patient derived intestinal organoids used to assess CFTR function.82 It is a repeatable and reproducible in vitro biomarker of CFTR function, thereby being potentially used to better evaluate individual disease expression, progression, and potential benefit of CFTR modulators.83

Currently, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, USA, is conducting an experiment on mRNA treatment, in which a nebulising device delivers normal CFTR-encoded mRNA to the lungs.84 MRT5005, a biosynthetic, codon-optimised mRNA, delivered by aerosol in lipid nanoparticles, failed to show any beneficial effects on FEV1 in clinical trials.85 Translate Bio (Lexington, Massachusetts, USA) has since discontinued the development of the drug.86 By attaching itself to the decoding location in the ribosome’s small subunit, Elx-02, an experimental read-through agent undergoing Phase II clinical trials, can cause translational read-through.87

Recently, the RNA editing tool, RESTORE (recruiting endogenous adenosine deaminase acting on RNA to specific transcripts for oligonucleotide-mediated RNA editing) has been able to modify the UGA nonsense codon of CFTR-G542X into a sense codon, allowing for synthesis of a full-length CFTR protein, offering a potential novel treatment strategy.88

CONCLUSION

Worldwide, people of all nations, races, and ethnicities are aware of the multisystem, life-limiting genetic disease known as CF. When making a differential diagnosis for children who have persistent or recurring respiratory infections, chronic malabsorption, and/or failure to thrive, CF should be considered as a differential because it is not as uncommon as previously believed. Research and treatment for CF has advanced significantly since its discovery, and nowadays an individual born with the condition can anticipate a moderately long and reasonably pleasant life. The issues surrounding screening, early identification, timely diagnosis, proper care, and enough follow-up continue to be a challenge that physicians and the national health system as a whole must accept. The development of medical centres and diagnostic facilities for the treatment of people with CF, as well as a management strategy for these patients based on locally accessible resources, is urgently needed.