Abstract

Introduction: Antihypertensive drugs effectively reduce chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression, yet research into their effectiveness for individuals with impaired glucose regulation (IGR) is limited. IGR, which refers to intermediate hyperglycaemia, including impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance, represents a high-risk metabolic state associated with both hypertension and accelerated CKD progression. This systematic review evaluates the effectiveness of hypertension treatment in delaying CKD progression in individuals with IGR and aims to provide insights into optimal drug-based treatments for this population.

Methods/Design: The electronic databases CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science, PubMed, Zetoc, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials, and grey literature will be searched for relevant studies from inception to 30th November 2025. Two independent reviewers will screen results, extract data, select studies for inclusion, and assess quality. Inclusion criteria encompass RCTs and non-randomised studies involving adults with IGR and hypertension, using CKD markers like estimated glomerular filtration rate, albumin creatinine ratio, protein creatinine ratio, serum creatinine, and creatinine clearance levels. The authors will estimate between-group and within-group differences, extracting effect measures such as relative risk, hazard ratio, or pre- and post-intervention means and SD, with 95% CIs. If applicable, study results will be pooled for a meta-analysis; high heterogeneity will prompt a narrative synthesis. Evidence quality and risk of bias will be evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) and Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I), respectively. This systematic review protocol is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024529193).

Conclusion: Current evidence supports antihypertensive drugs in slowing CKD progression, but research on individuals with IGR is limited. This review explores effective drug-based treatment strategies for adults with CKD and IGR, enhancing clinical practice and patient outcomes.

Key Points

1. People with impaired glucose regulation and hypertension are at higher risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Treatment decisions should consider kidney function, stage of CKD, blood pressure control, patient preferences, medication side effects, and likelihood of adherence.2. Various antihypertensive drugs have been studied, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, beta-blockers, diuretics, and newer agents such as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, either alone or in combination, with a focus on protecting kidney function.

3. No single treatment works for everyone. The review aims to clarify which drug strategies are most effective in slowing CKD progression in adults with impaired glucose regulation, helping clinicians make personalised treatment decisions.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a significant public health concern that leads to higher mortality, increased illness, and reduced quality of life.1 It is a common, progressive condition that is often asymptomatic and can occur alongside other health issues.2 CKD is a long-term condition characterised by a gradual decline in kidney function lasting more than 3 months, regardless of the presence of kidney damage.3

CKD is classified into five stages based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and markers of kidney damage. Stage 1 reflects normal or high eGFR (≥90 mL/min/1.73m²) with evidence of kidney damage; Stage 2 indicates mildly decreased eGFR (60–89 mL/min/1.73m²); Stage 3 is divided into moderate reduction (3a: 45–59; 3b: 30-44 mL/min/1.73m²); Stage 4 represents severely reduced eGFR (15–29 mL/min/1.73m²); and Stage 5 corresponds to kidney failure (<15 mL/min/1.73m²) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD), with proteinuria or albuminuria used to further characterise severity.4

The estimated annual cost to the NHS for CKD is 1.4 billion GBP.5 The most common method for diagnosing CKD is by using the eGFR derived from serum creatinine. CKD is diagnosed when there are two or more eGFR values of less than 60 mL/min/1.73m2 at least 3 months apart.6 More recent data from the Global Burden of Disease Study (2023) estimate a global age-standardised CKD prevalence of 14.2%, which shows that CKD is still a common condition worldwide.7 Individuals with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes (T2D) are reported to have a significantly higher risk of developing CKD compared to the general population, with a 1.75–5.00 times increased risk.8 The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) found that 29% of patients with newly diagnosed T2D developed renal impairment over a median follow-up period of 15 years.9 Additionally, data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999–2006 showed that the prevalence of CKD was 39.6% in individuals with diagnosed diabetes, 41.7% in those with previously undiagnosed diabetes (fasting plasma glucose [FPG]: ≥126 mg/dL), 17.7% in individuals with pre-diabetes (FPG: ≥100 and <126 mg/dL), and 10.6% in those without any glycaemic abnormalities.10

Hypertension and impaired glucose regulation (IGR) share common underlying mechanisms such as insulin resistance, oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction.11 These factors contribute to the development of hypertension and worsen insulin resistance, leading to IGR. In CKD, the coexistence of hypertension and IGR complicates disease progression. Hypertension can directly damage the kidneys and exacerbate metabolic disturbances associated with IGR, accelerating renal dysfunction.

CKD in individuals with prediabetes is less investigated compared with T2D, despite the similar aetiology, including insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and early β-cell dysfunction, and the common progression of prediabetes into T2D. Insulin resistance, a hallmark of IGR, has been independently associated with the development and progression of CKD, even in individuals without diabetes.12-15 This provides a rationale for specifically reviewing the effectiveness of antihypertensive interventions in this population. Pre-diabetes refers to impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and IGT, collectively known as IGR. People with IGR have blood glucose levels that are higher than normal, but not high enough to be diagnosed with diabetes.16 The International Expert Committee (IEC) recommends using the HbA1c assay for diagnosing diabetes, with a threshold of ≥6.5% (≥48 mmol/mol). Prediabetes/IGR is defined as an HbA1c of 6.0–6.4% (42–47 mmol/mol), an FPG of 6.1–6.9 mmol/L (WHO) or 5.6–6.9 mmol/L (American Diabetes Association [ADA]), or a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) plasma glucose of 7.8–11.0 mmol/L. Individuals meeting any of these criteria are considered at high risk of developing diabetes.17,18

According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) in 2021, an estimated 10.6% (541 million) of adults worldwide have IGT, which is projected to increase to 11.4% (730 million) by 2045. Conversely, an estimated 6.2% (319 million) have IFG, which is projected to rise to 6.9% (441 million) by 2045.19 Furthermore, a study conducted in England revealed a significant increase in pre-diabetes prevalence from 11.6% in 2003 to 35.3% in 2011 among adults aged 16 years and older.20 These data highlight the growing burden of IGR on a global scale, and the need to understand the treatment options for IGR and associated CKD-related risks and treatments.

Diabetes and hypertension are significant risk factors for the development and progression of CKD. CKD caused by these conditions affects nearly 5–7% of the global population.1 The coexistence of diabetes and hypertension, when not well controlled, significantly increases the risk of CKD and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. While current treatments can slow the progression of diabetic-hypertensive nephropathy, many patients still develop ESRD.9,21

A comprehensive meta-analysis conducted by Casas et al.22 examined 127 clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of various classes of antihypertensive drugs in patients with high-risk hypertension, including patients who are diabetic and non-diabetic. The study found that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) slightly reduced the incidence of ESRD in patients with nondiabetic nephropathy compared to other antihypertensive drugs. However, this effect was less significant in larger studies with ≥500 participants.

In patients with diabetic nephropathy, ACE inhibitors and ARBs were not more effective in slowing renal disease progression compared to other antihypertensive drugs. The researchers cautioned that the results should be interpreted carefully due to potential bias from smaller studies. Since then, additional analyses have been published, including Xie et al.23 and Zhang et al.,24 which further examined the effects of ACE inhibitors and ARBs on CKD progression. Overall, these studies support a modest benefit of renin-angiotensin system blockade in reducing the incidence of ESRD in both diabetic and non-diabetic populations, though effect sizes vary according to study design and patient characteristics.

In a separate study, the ROADMAP trial examined whether the ARB olmesartan could delay the onset of microalbuminuria in patients with T2D and hypertension. Although many ARB studies have demonstrated renoprotective effects, ROADMAP is notable because it evaluated early renal outcomes and included individuals at the stage of dysglycaemia prior to advanced kidney damage. The trial reported that olmesartan delayed the development of microalbuminuria by 25% compared with placebo over a median follow-up of 3.2 years, independent of baseline blood pressure (BP) levels and the degree of BP reduction.25 In contrast, a meta-analysis of 11 RCTs comparing the effectiveness of antihypertensive regimens containing ACE inhibitors in patients who are non-diabetic with renal disease compared to placebo found that regimens containing ACE inhibitors were more effective in slowing the progression of kidney disease compared to regimens without ACE inhibitors, after adjusting for patient and study characteristics.26

However, a Cochrane review concluded that there was insufficient evidence to determine whether ACE inhibitors and ARBs, either alone or in combination, were more effective in preventing the progressive decline of kidney function or reducing urinary protein and creatinine clearance in patients who are non-diabetic. More recent evidence provides additional clarity: a Cochrane review by Cooper et al.27 evaluated ACE inhibitors and ARBs in adults with Stage 1–3 non-diabetic CKD and reported benefits, including slower progression of kidney function decline and reductions in albuminuria.

In a prospective study of 652 non-diabetic individuals aged ≥65 years from Taiwan, the impact of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance on the progression of CKD and decline in renal function was assessed. The presence of individual components, such as high BP, serum triglycerides, fasting plasma glucose, waist circumference, and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, was linked to a higher prevalence of CKD. Individuals with elevated BP (≥130/85 mmHg) were found to be twice as likely to develop CKD, with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.0 (95% CI: 1.4–2.9; p<0.001). After adjusting for factors like body weight, systolic BP, fasting blood glucose, and serum creatinine, the risk of developing CKD was attenuated, but remained statistically significant (OR: 1.8; 95% CI: 1.2–2.5; p=0.004).28

Treatments of hypertension in individuals with IGR are crucial for controlling CKD progression and mitigating associated metabolic risks. Drug-based interventions using antihypertensive medications have a dual role in improving BP as well as glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and renal function outcomes. However, current treatments primarily centre around managing individuals who are diabetic with CKD through hypertensive medications and present inconclusive results, with the majority of studies having small sample sizes.29-31 Comparable interventions in individuals with IGR are lacking. A systematic review is necessary for assessing the effectiveness of antihypertensive drug interventions for CKD stages and IGR. This review aims to fill knowledge gaps and provide recommendations for personalised interventions in this underrepresented population.

RESEARCH QUESTION

To test whether and how antihypertensive drugs are effective in slowing CKD progression at different stages in adults with IGR.

AIMS

To systematically review and evaluate both RCTs and non-RCTs that examine the impact of hypertension treatment in delaying/slowing the progression of CKD in individuals with IGR.

To investigate different drug treatment approaches, such as comparing the effectiveness of various hypertensive medications/treatments in delaying/slowing the progression of CKD in individuals aged 18 years and older with IGR.

METHODS

This review protocol adheres to the reporting guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P)32 (Appendix 1), and follows the methodological recommendations for conducting systematic reviews as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for diagnostic test accuracy.33 This systematic review protocol is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024529193).

Search Strategy

The following citation databases, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, ZETOC, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials, PubMed, and Google Scholar, along with database-specific filters for RCTs (where available), and key journals/grey literature, will be searched from inception to 30th November 2025. An optimum search strategy (Appendix 2) has been developed to identify relevant articles focusing on key terms such as CKD, prediabetes, IGT, IFG, metabolic syndrome, IGR, hypertension treatment, including interventions such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics, beta-blockers for hypertension, RCTs, and clinical trials. Only articles published in English will be included.

Inclusion criteria

Studies that have been published in peer-reviewed journals as well as grey literature will be considered for inclusion. Both RCT and non-RCT studies focusing on BP-lowering treatment will be included, together with CKD defined by a validated measure at baseline. As Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria3 for CKD were introduced in 2002, studies conducted before this may use different definitions of CKD. These differences will be considered a potential source of heterogeneity, and pre-2002 studies will be assessed as higher risk of bias in the selection domain of Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) due to the possible misclassification of CKD. The studies will be followed up in individuals with IGR/prediabetes and hypertension or on an anti-hypertensive drug. The selection criteria for including or excluding studies will adhere to the participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design framework.34

Population

The review population consists of individuals with IGR and hypertension who also have baseline kidney damage. Adults (≥18 years) diagnosed with IGR, also known as ‘pre-diabetes’ or ‘pre-diabetic state’. Pre-diabetes can refer to either IGT or IFG,35 or metabolic syndrome, where IGR is part of the metabolic syndrome. For the purposes of this review, IGR will be defined as an FPG level <7 mmol/L or an OGTT result ≥7.8 mmol/L and <11.1 mmol/L, or an HbA1c level of 6.0–6.4% (42–47 mmol/mol).36 The authors will also consider studies using alternative definitions for prediabetes according to the ADA, which defines HbA1c as 5.7–6.4% (39–47 mmol/mol) and FPG as 5.6–6.9 mmol/L. Where studies report differing definitions, sensitivity analyses will be conducted to explore the impact of these variations on outcomes.18 The second requirement is a diagnosis of hypertension, indicated by a systolic BP of 140 mmHg or higher, a diastolic BP of 90 mmHg or higher, or the use of anti-hypertensive medication.37 The third requirement is evidence of kidney damage, indicated by markers such as proteinuria, abnormal findings on imaging, reduced eGFR, or histological abnormalities identified on biopsy.

Study type and intervention

RCTs and non-RCTs investigating interventions for lowering BP, involving a range of pharmacological interventions, including ACE inhibitors, ARBs, diuretics, and beta-blockers. These include comparing BP-lowering drugs with placebos, assessing the effectiveness of different BP-lowering medications, and examining different BP-lowering targets. Studies in which participants are receiving glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists or sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors will also be included; however, their independent effects on renal function will be extracted and considered in sensitivity analyses as potential confounders. If studies do not report stratification by these medications, this will be noted as a potential source of bias in the risk of bias assessment. In trials with multiple active groups, including those comparing different drug classes, the group with the greater reduction in BP will be considered the intervention, while the other treatment group(s) will be considered comparators. Trials comparing more intense versus less intense treatments will be categorised as intervention and comparator groups, respectively.

Comparator

In the case of RCTs, individuals may receive no hypertension/BP lowering treatment. Comparator groups can include true controls (i.e., no intervention provided or standard care) or groups receiving alternative hypertension/BP lowering treatments. In non-RCTs, individuals in the comparator groups may receive either standard care (i.e., routine clinical practice without specific intervention) or alternative hypertension/BP-lowering treatments.

Outcome measures

Studies will need to define CKD using various measures, such as eGFR Stages 3A, 3B, 4, and 5; albuminuria; albumin creatinine ratio (≥2.5 mg/mmol or ≥30 mg/g), protein creatinine ratio (≥45 mg/mmol or ≥300 mg/g), serum creatinine (1.0 mg/dL or ≥50 μmol/L), and creatinine clearance (≥60 mL/min),38 or other relevant markers of CKD progression.

Follow-up

To reduce the potential impact of small study effects, all RCTs investigating BP/hypertension treatment must include at least 1,000 person-years of follow-up in each study arm.39 If some studies do not reach 1,000 person-years of follow-up, sensitivity analysis will be performed, and a meta-analysis will be considered if feasible. A meta-analysis will only be conducted if there are sufficient studies with comparable interventions, populations, and outcome measures, and if statistical heterogeneity is low (I² <50%). If the included studies are too few, too heterogeneous, or report outcomes are in incompatible formats, a narrative synthesis will be performed instead.

Measures of effect

For RCTs, differences between groups at the end of the intervention will be assessed, while within-group differences will be analysed for non-randomised study interventions. Effect measures such as relative risk (RR) or hazard ratio (HR) and their corresponding 95% CIs will be extracted. HR was included as it considers time-to-event data and accounts for censoring.40 To account for the competing risk of death from cardiovascular disease, particularly in non-ACE inhibitor/ARB comparator groups, studies reporting cause-specific hazards or accounting for competing events will be extracted separately. Where competing risks are not addressed, this will be noted and considered in sensitivity analyses, as it may mask differences in CKD outcomes between intervention and comparator groups. Studies reporting mean difference or standardised mean difference (SMD) for changes in kidney function or biomarker levels over time will be extracted along with 95% CI and p values if available or calculable from raw data. For this review, only guideline-endorsed biomarkers such as eGFR (based on serum creatinine or cystatin C) and albuminuria will be considered as primary outcomes. Other biomarkers will only be extracted if they are reported consistently and are relevant to CKD progression, but they will be analysed separately and considered exploratory. Group effect size will also be extracted and reported.

Exclusion criteria

- Aged <18 years.

- Studies that do not focus on individuals with IGR.

- Studies focusing solely on Type 1 diabetes or T2D.

- Studies that do not assess the effectiveness of hypertension treatment in preventing CKD or slowing progression in individuals with baseline CKD Stages 3–4 (eGFR: 15–59 mL/min/1.73 m²) will be excluded.

- Studies with insufficient data or inadequate reporting of the outcome of interest.

- Review articles, single case studies, case reports, letters, editorials, studies with only abstracts, and any other literature with no full-text availability, as well as articles not published in the English language, will be excluded.

- Severe medical or psychiatric conditions.

- Drug or alcohol abuse.

- Specialist CKD care, including dialysis.

ELIGIBILITY SCREENING PREPARATION

Prior to starting the eligibility screening process, the search results from the specified databases will be compiled into a digital library and organised by database using EndNote V.20 software (Clarivate Analytics, London, UK), a reference management tool. Duplicate articles will be identified and removed in this phase.

Study Selection

Two reviewers (Jadhakhan and Safi) will independently review titles and abstracts in the digital library to identify studies that potentially meet the predetermined inclusion criteria. They will then independently screen full-text articles and apply eligibility criteria to select studies for inclusion in the review. Any disagreements over eligibility will be resolved through consensus, with a third reviewer (Alkhatib) available to arbitrate if needed. An inclusion criteria checklist (Table 1) has been developed to ensure that studies are classified and interpreted correctly. A PRISMA-P flow diagram will be included to outline the selection process and reasons for exclusions.

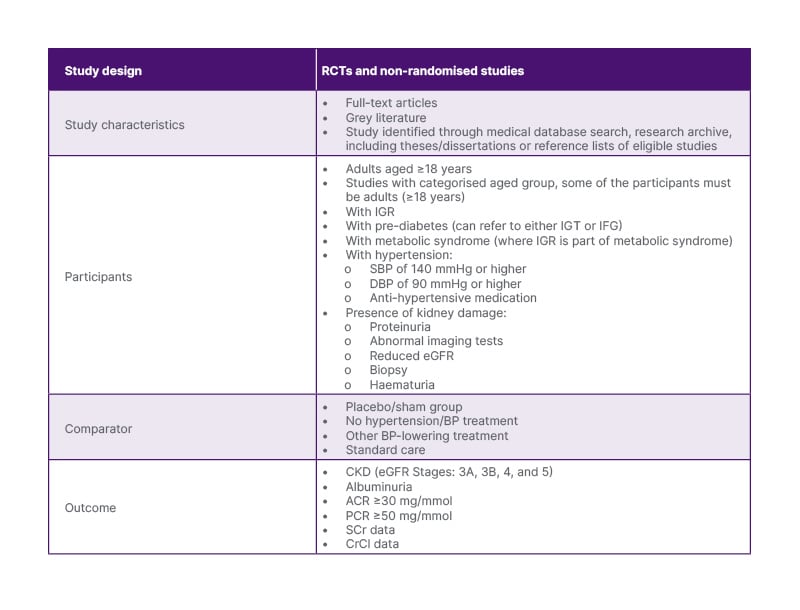

Table 1: Review eligibility criteria checklist.

The table details the study design, characteristics, participant criteria, comparator groups, and outcome measures specified in the systematic review protocol. It includes specific criteria for selecting RCTs and non-RCTs that assess the efficacy of antihypertensive medications in delaying the progression of CKD in adults with IGR.

ACR: albumin creatinine ratio; BP: blood pressure; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CrCl: creatinine clearance; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; IFG: impaired fasting glucose; IGR: impaired glucose regulation; IGT: impaired glucose tolerance; PCR: protein creatinine ratio; SCr: serum creatinine; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

PATIENT AND PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT

No patients or members of the public were directly engaged in the design, writing, or editing of this systematic review protocol.

DATA EXTRACTION

Data will be organised using EndNote V.20 software (Clarivate Analytics) to facilitate reviewers’ access, eliminate duplicates, create groups by database, and store full texts and abstracts efficiently. Data from the studies will be extracted by two reviewers independently. Any disagreements regarding study eligibility will be resolved by engaging in discussions with a third reviewer. Efforts will be made to contact study authors at least twice via email and/or phone to obtain additional information for any missing data. The following information will be extracted from each study: authors and year of publication, study location, study design, participant characteristics, outcomes of interest (markers of CKD), sample size, duration of follow-up, study setting, items related to risk of bias, summary statistics, and statistical analysis methods. Details of the intervention, including BP-lowering/anti-hypertensive treatment, types, duration, frequency, and control/comparison group where applicable, as well as study methodology, outcomes, and measurement/follow-up, will be extracted and reported. Two reviewers will independently carry out data extraction from each study using a predetermined data extraction form. Extracted outcome data will consist of pre-intervention and post-intervention mean and SD, as well as RR and HR where applicable. Between-group differences will be assessed at the end of the intervention, with within-group differences analysed for non-randomised study interventions. Data presented as medians or other measures of spread will be converted to mean and SD. If only figures are provided without numerical data in the text, the data will be extracted and analysed where possible using software tool such as Web Plot Digitizer (Webplot Digital Services LLP, Gurugram, India).41

RISK OF BIAS ASSESSMENT

The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool V.2 (RoB 2; Cochrane Bias Methods Group, London, UK)42 will be used to assess the risk of bias in each of the randomised trials. Potential biases may include selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of patients/research team), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete or missing outcome data), and reporting bias (selective reporting of outcome data). The ROBINS-I tool will be used to assess bias in non-randomised intervention studies.43 The quality assessment of the studies will be done by two reviewers (Jadhakhan and Safi), with any disagreements resolved by a third reviewer (Alkhatib). This review will use the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology to evaluate the quality of the pooled evidence.44

DATA ANALYSIS AND SYNTHESIS

A random-effects meta-analysis will be performed, taking into account the effect measures presented in the studies and the similarities among individual studies regarding interventions and outcomes.45 Statistical heterogeneity will be assessed following guidelines by Higgins et al.46 Meta-analysis will be conducted if there is low heterogeneity between the studies (I² <50%). The variability in study outcomes will be evaluated through the I² statistical analysis. Individual study HRs and RR with 95% CIs will be extracted for each outcome before pooling. For the continuous measurement of CKD markers, SMD and 95% CIs will be extracted and reported as effect estimates. SMD and corresponding Cohen’s D values, where available, will be extracted and reported or calculated using the Cohen’s D formula. Effect size will be categorised as small (0.0–0.2), medium (0.3–0.7), and large (>0.8), with a corresponding 95% CI calculated where possible. If there is significant heterogeneity and bias present in the studies, preventing a pooled analysis, a narrative summary of the outcomes from selected studies will be conducted and included in the final review. The analysis will be carried out using Stata V.17.0 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA).

Heterogeneity Assessment

Univariate and multivariate meta-regression will be conducted to examine sources of variation between studies. Statistical significance will be set at p<0.05. Covariates such as sample size, country, study setting, duration of hypertension/CKD, medication adherence, baseline renal function/IGR, comorbidities, BMI/obesity, age, lipid profiles, smoking status, and diversity of outcome measures will be examined to explore sources of heterogeneity. Significant covariates from univariate models will be included in a multivariate meta-regression model. The meta-regression analysis will be carried out in Stata using the ‘metareg’ command.47

Sensitivity Analysis

Various sensitivity analyses will be performed to assess the methodological rigour and address potential sources of heterogeneity among the included studies. Factors such as the assessment tools for hypertension, CKD, and IGR, duration of follow-up, baseline renal function, type of hypertension treatment, comorbidities, BMI/obesity, age, lipid profiles, smoking status, sampling strategies, and response rates to treatment will be considered. These factors will be stratified, and separate sensitivity analyses will be carried out to examine their potential influence on the outcomes. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis will be conducted by excluding studies with a high risk of bias to ensure the reliability of the results.

Narrative Synthesis

If there is a high level of heterogeneity between studies that prevents pooling the data, a narrative summary of the outcomes from the selected studies will be provided in the final review. This detailed analysis will explain the reasons for the results reported in each study.

Publication Bias and Overall Quality of the Evidence

Publication bias will be evaluated through visual examination of the inverted funnel plot technique, as well as using the Begg rank test48 and the Egger regression test.49 The extent of publication bias will be assessed using the trim and fill method,50 which estimates the number of missing studies due to publication bias and imputes missing effect sizes until the funnel plot is symmetrical. The effect size will be recalculated using the standard meta-analysis approach. The Stata command metatrim51 will be utilised for the non-parametric trim and fill method. The GRADE framework44 will be applied to assess the quality and consistency of studies, considering factors such as publication bias, imprecision, inconsistency, and indirectness of study results. The quality of the summary evidence will be evaluated as high, moderate, low, or very low in accordance with GRADE. It is recommended to include a minimum of 10 studies when assessing publication bias.52

DISCUSSION

The proposed systematic review aims to fill a gap in current research by investigating the effectiveness of hypertension treatment in individuals with IGR in preventing CKD. Existing studies have primarily focused on individuals with T2D, leading to inconclusive findings and limitations such as small sample sizes. This review will specifically examine which antihypertensive regimens are beneficial for individuals with IGR. The review will employ a comprehensive search strategy tailored to each database, rigorous quality appraisal, and heterogeneity assessment methods. Potential limitations include variations in diagnostic methods, study settings, and publication bias. A narrative summary of study outcomes will be provided to address any discrepancies. While no prior reviews have explored this specific research question, relevant existing reviews will be considered, and a meta-analysis may be conducted if feasible, dependent on the number of studies analysed.

CONCLUSION

In summary, this systematic review protocol outlines a comprehensive approach to assess the efficacy of antihypertensive drugs in slowing CKD progression in adults with IGR. By synthesising data from various studies, the goal is to provide insights for evidence-based interventions in hypertension treatment for the management of CKD in this specific population.