INTRODUCTION

In the context of increasing healthcare complexity and chronic disease prevalence, patient engagement is gaining recognition as a key driver of successful preventive strategies. This article explores how patient engagement, defined as a multidimensional psychological process involving emotional, cognitive, and behavioural activation, can enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of preventive medicine. Drawing on recent scientific literature, including the Patient Health Engagement (PHE) model and empirical studies by Graffigna and others, this feature highlights how engaged patients are more likely to adopt healthy behaviours, adhere to preventive guidelines, and develop trust in health systems. It also discusses psychological drivers of engagement, the role of digital health tools, the social determinants of health, and the importance of equity in engagement strategies. The findings support the view that fostering patient engagement is essential to move from passive healthcare consumption to active health citizenship.

AN EVOLVING PARADIGM IN PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

In recent years, the concept of patient engagement has gained increasing attention as a key element in improving healthcare outcomes and sustainability. This is particularly true in the field of preventive medicine, where success often depends not only on clinical efficacy but also on individual behaviours, motivation, and trust in health systems. Patient engagement is defined as the active, informed, and sustained involvement of individuals in their health and healthcare decisions. It is a multidimensional process encompassing emotional, cognitive, and behavioural elements that reflect a person’s psychological readiness and motivation to take part in their own care. An engaged patient is more likely to adopt preventive behaviours, seek timely care, and collaborate with providers. In contrast, disengaged individuals may avoid preventive services, exhibit mistrust toward healthcare systems, or feel unable to influence their health outcomes, often due to social or systemic barriers. A growing body of scientific literature emphasises that involving patients as active partners in their care can lead to better adherence to preventive protocols, more efficient health services, and, ultimately, healthier populations. For example, engaged individuals are more likely to participate in vaccination campaigns, attend routine screenings, and follow health-promoting recommendations.1,2 These behaviours are fundamental to reducing the incidence of chronic diseases and lowering long-term healthcare costs. Engagement also plays a protective role against misinformation and vaccine hesitancy. Research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted how engaged citizens were more willing to adopt public health measures and less susceptible to disinformation.3,4 This indicates that engagement fosters a more resilient and cooperative health culture, especially in times of crisis.

The shift toward patient engagement in preventive medicine reflects a broader transformation in healthcare philosophy, from a paternalistic model to one based on partnership and shared responsibility. Patients are no longer seen merely as recipients of care but as co-creators of their health outcomes. This transformation requires not only behavioural change on the part of patients but also cultural and structural change within healthcare systems. By fostering trust, competence,5 and motivation, engagement becomes one of the essential components of effective prevention. It enables people to see health not just as a clinical goal, but as a personal and social project worth investing in.

As research in this field continues to grow, it becomes increasingly clear that preventive medicine cannot succeed without engaging the people it aims to protect. Promoting patient engagement is not solely the responsibility of individual professionals; it requires system-level change. Training healthcare providers in communication and psychological skills is a first step.6 Equally important is designing care pathways that allow time and space for meaningful patient participation. Health systems that invest in engagement strategies may see long-term benefits in terms of cost-effectiveness, quality of care, and health equity. Preventive care, when combined with high engagement levels, can reduce the burden of chronic diseases and increase overall population resilience. In this sense, engagement is not an optional add-on but a fundamental component of sustainable healthcare.

PSYCHOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS OF ENGAGEMENT: THE PATIENT HEALTH ENGAGEMENT MODEL

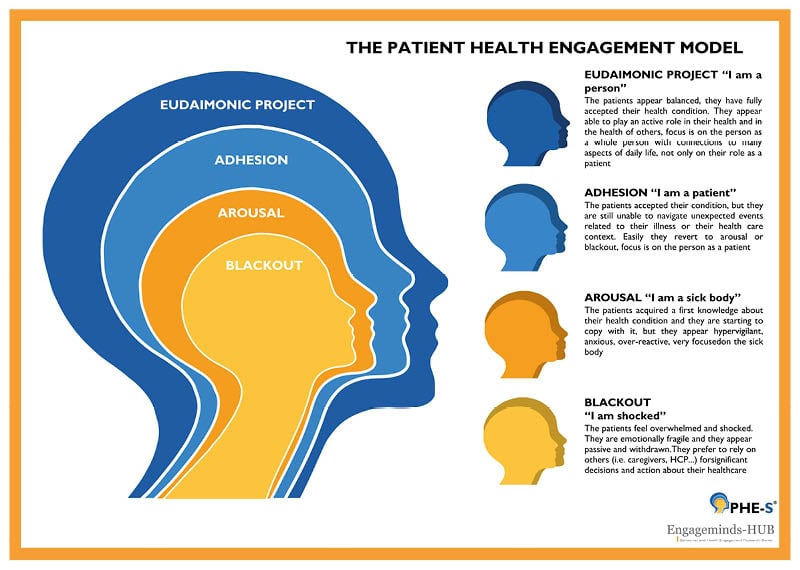

The development of patient engagement relies on specific psychological conditions. According to the literature, key drivers include self-efficacy,5 perceived autonomy, and relational trust with healthcare providers. These findings align with principles from Self-Determination Theory, suggesting that patients are more likely to adopt preventive behaviours when they feel competent, in control, and supported. Therefore, communication strategies that promote preventive care should not only aim to inform but also to empower. Messaging that resonates with individual values, emotional states, and daily realities is more likely to activate and sustain engagement. This implies a shift from didactic, top-down campaigns to personalised, empathic interactions between systems and citizens. Patient engagement is understood as a multidimensional process, encompassing emotional, cognitive, and behavioural components. It goes beyond mere compliance with medical advice, involving a deeper psychological investment in one’s health management. Several models have been proposed to conceptualise this process. Among them, the PHE model, developed and validated in multiple studies,7,8 offers a structured approach that traces individuals’ emotional and motivational responses as they transition from passive subjects to proactive health agents.The PHE model describes patient engagement as a progressive journey based on psychological readiness to take an active role in health (Figure 1). It consists of four distinct phases:

- Blackout (emotional shutdown)

- Arousal (heightened awareness with uncertainty)

- Adhesion (early behavioural alignment)

- Eudaimonic Project (full integration and self-realisation)

Each phase is characterised by a different way of coping with health demands and implies varying degrees of support needs.

Figure 1: The PHE-s® model.

Copyright Graffigna et al.7 2015.

Blackout

This phase typically arises in moments of psychological vulnerability, such as after a difficult diagnosis, a major health scare, or even a preventive screening result that triggers fear. Individuals feel overwhelmed and disconnected from their ability to take care of themselves. Health behaviours may feel incompatible with one’s lifestyle or identity, leading to inaction, sadness, or denial. These individuals often rely heavily on formal and informal caregivers.

Arousal

Here, individuals begin to acknowledge their health condition or risk. However, their knowledge and skills are still limited, and they may experience anxiety and hypervigilance. Preventive messages can be confusing or overwhelming. Support is needed to help them organise information, build self-efficacy, and develop positive expectations about their ability to act.

Adhesion

People in this phase show good acceptance and awareness of their condition or health risks. They comply with recommendations but still view them as external obligations rather than integrated habits. Health behaviours are not yet part of daily routine, and unusual events may trigger non-adherence. These individuals benefit from structured routines, simple self-management tools, and encouragement to act autonomously.

Eudaimonic Project

From the Greek εὐδαιμονία (eudaimonia, ‘good spirit’), this phase reflects a full integration of health into one’s identity and purpose. Preventive behaviours become part of the person’s lifestyle and long-term goals. However, even in this phase, setbacks (e.g., new stressors, illness, life changes) may require renewed support and re-engagement. Peer networks, empowerment tools, and continuity of care are key to maintaining engagement.

Although the PHE model was originally developed for patients with chronic illness, it is argued that its principles can also apply to preventive medicine. Even individuals without a diagnosis can move through these psychological stages in response to perceived risk, medical advice, or health communications. For example, someone at high risk of diabetes or cardiovascular disease may initially reject preventive messages (blackout), feel confused about recommendations (arousal), begin adopting changes (adhesion), and eventually internalise a new lifestyle (Eudaimonic Project). Thus, the model offers valuable insight into how people psychologically engage with preventive care.

However, poverty, housing, employment, and education intersect with patient engagement and preventive behaviours. Thus, engagement cannot be considered purely an individual matter but socially mediated. Promoting engagement needs a process-like, systemic vision, in order to enable changes and participation at the micro level (direct care), the meso-level (healthcare organisation and management) and the macro-level (policy making) of the healthcare system.9

IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH SYSTEMS AND POLICY

This framework has particular relevance for preventive care, where individuals are often asked to take action in the absence of immediate symptoms. Whether it’s undergoing screenings, adopting healthier lifestyles, or getting vaccinated, these decisions require a degree of engagement that goes beyond information, they require conviction, trust, and a sense of personal responsibility. Despite its promise, not all individuals engage equally with preventive services. Socioeconomic status, cultural background, health literacy, and past experiences with the healthcare system all influence the degree to which people feel capable and willing to participate. We recognise that engagement is strongly influenced by structural inequalities. Broader social policies are needed to enable universal access, community networks, and workplace protections, which are key to nurturing health engagement and participation. Digital inequality also impacts on the ability to get engaged. There is thus an urgent need for equitable strategies that adapt to diverse needs, particularly among vulnerable or marginalised populations. Inclusive communication strategies, co-design practices, professional training, and integration of digital tools tailored to diverse populations are needed. Examples include the use of multilingual communication, community-based outreach, and inclusive digital solutions designed for people with limited access or digital literacy. Without such considerations, engagement efforts risk widening health disparities rather than closing them. Digital health technologies are increasingly used to support patient engagement in prevention. Mobile apps, wearable trackers, telemedicine, and AI-based decision aids offer opportunities to monitor health behaviours and deliver tailored feedback. However, research emphasises that the effectiveness of these tools depends largely on their design and user experience. If implemented without regard for user engagement, such tools risk being ignored or misused. Scholars argue for a human-centred and co-design approach, involving users early in the development process to ensure the tools align with their motivational and emotional needs.10 Furthermore, digital technologies should be integrated with, not replace, the human aspects of care, such as empathy, continuity, and trust.

CONCLUSION

Patient engagement is increasingly recognised not as a marginal aspect of care, but as a core element of effective preventive medicine. The evidence suggests that when individuals are supported in becoming emotionally and cognitively involved in their health decisions, their capacity to act preventively increases. This shift requires a transformation in how healthcare systems communicate, design services, and interact with their populations, moving from information delivery to genuine activation and empowerment. To make engagement a tangible lever for prevention, health institutions must invest in personalised communication, inclusive technologies, and a culture that values the patient’s voice. Moreover, attention to equity is critical: engagement strategies must reach beyond the “already engaged” and include marginalised groups, reducing barriers to participation.

In a healthcare era increasingly defined by chronic disease, pandemics, and resource constraints, the proactive role of the patient is not optional, it is indispensable. Engagement transforms prevention from a policy goal into a lived, shared responsibility. When patients are seen, and see themselves, as active partners, preventive medicine becomes not only more effective, but more humane and sustainable.