INTRODUCTION

TEST In this feature, the authors critically analyse the European standards for Haemophilia Treatment Centres (HTC), examining their applicability across socioeconomic and geographical settings, particularly in regions such as India. The authors explore the disparities in healthcare delivery, and highlight how global variations in resources, infrastructure, and clinical expertise can limit the feasibility of adhering to uniform European benchmarks. To address these challenges, the authors propose an inclusive classification system (a universal stratification model) that accounts for these contextual differences. This model allows for progressive functionality in both clinical and laboratory services, enabling centres to optimise haemophilia care delivery based on available resources. The authors also emphasise the role of quality improvement processes and the establishment of key performance indicators (KPI), which together can pave the way for certification and accreditation pathways, ultimately strengthening patient outcomes and system accountability.

PHILOSOPHY OF HAEMOPHILIA CARE

‘Principle’ is a fundamental truth or proposition that serves as the foundation for a system of belief, behaviour, or reasoning.1 Principles of care are the core values that underpin care delivery, ensuring that individuals are treated with dignity, respect, and compassion while promoting their independence and choice. Standards of care are specific, measurable guidelines and expectations for healthcare providers that define the minimum level of care a patient should receive in particular situations or medical conditions.

In 2008, the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders (EAHAD) published 10 European principles of haemophilia care through the interdisciplinary working group. This gave the provision for elements of haemophilia care that should be available in each European country.2 In 2018, the Asia-Pacific Haemophilia Working Group (APHWG) prepared a document with 12 principles of care relevant to its perspective on the context-specific development of haemophilia care.3 In 2020, the 3rd edition World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) guidelines for the management of haemophilia enumerated 12 principles of care that had some overlap with the previous two principles of care publications.4 The purpose of these publications was for planning, and for them to serve as an advocacy tool to enhance care for people with haemophilia.

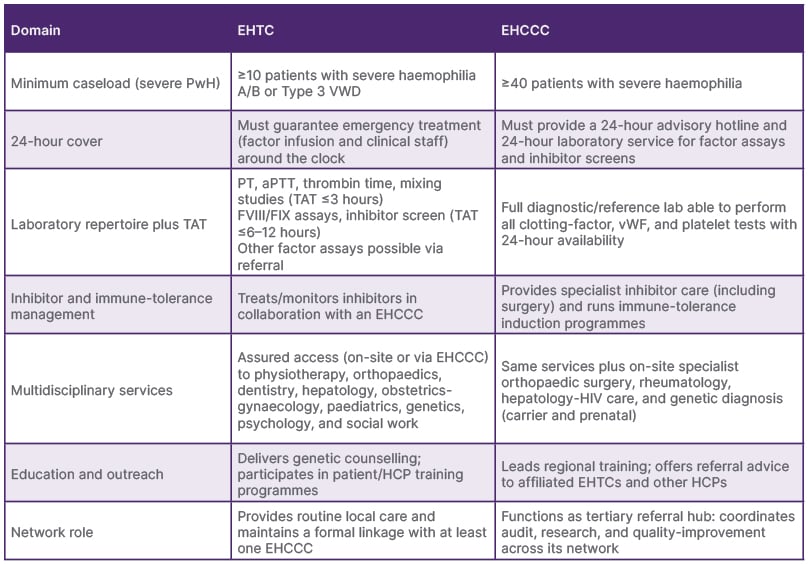

In 2014, the European standards for haemophilia centres5 were established through a consensus process by the European Haemophilia Network (EUHANET) with the help of national health authorities, health professionals, patient organisations, and EUHANET Project Partnership.6 The guidelines defined the standards and criteria of two levels of care delivery: European Haemophilia Treatment Centres (EHTC), providing local routine care, and European Haemophilia Comprehensive Care Centres (EHCCC), providing specialised and multi-disciplinary care, and functioning as tertiary referral centres (Table 1).

Table 1: European Haemophilia Treatment Centre and European Haemophilia Comprehensive Care Centre standards.5

aPTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; EHCCC: European Haemophilia Comprehensive Care Centre; EHTC: European Haemophilia Treatment Centre; FIX: Factor IX; FVIII: Factor VIII; HCP: healthcare professional; PT: prothrombin time; PwH: persons with haemophilia; TAT: turn-around-time; vWF: von Willebrand factor.

The intention was to implement the certification of haemophilia centres, which would contribute to the reduction of health inequalities through the standardisation of the quality of care in EU member states. Today, there are 409 known haemophilia centres in Europe, with 5–350 persons with haemophilia being treated.7 Of those centres, 45 are EHTCs and 128 are EHCCCs among 34 countries, ranging from 1–23 centres per country.

While this is an excellent concept, centres in other parts of the world may find it challenging to meet the same standards due to socioeconomic or geopolitical challenges in many regions. This discrepancy creates a false dichotomy, as it overlooks the diverse range of care levels worldwide, and does not adequately account for the distinct realities that HTCs face in different contexts. A survey on adherence to this classification conducted in 21 centres across 14 European countries revealed that 36% of patients received treatment outside of centres that met the definition of EHTCs or EHCCCs.8 The feasibility of implementing the proposed model is based on only a pilot study, and the authors acknowledge that further validation across other low- and middle-income countries will enhance its scalability.9

In 2017, a pilot study conducted in India assessed the care provided by various HTCs, with a focus on categorising laboratory and clinical services. Among the 52 centres surveyed (85% response rate) across 17 states, only 53% had functional laboratories, despite offering haemophilia care. Only four centres met the criteria for EHTCs, and only two qualified as EHCCCs.

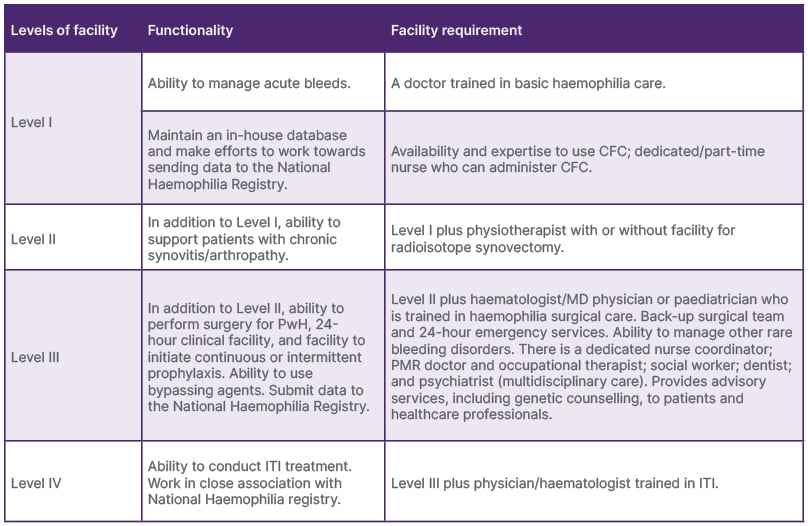

While all centres managed acute bleeds, only half addressed chronic joint disease (Level III), and 16% performed surgeries (Level II). Only one-third of the laboratories also adhered to quality control standards and conducted factor assays9 (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2: The levels of clinical services in Haemophilia Treatment Centres.

CFC: factor concentrate; HTC: Haemophilia Treatment Centre; ITI: immune tolerance induction; MD: Doctor of Medicine; PMR: Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: PwH: persons with haemophilia.

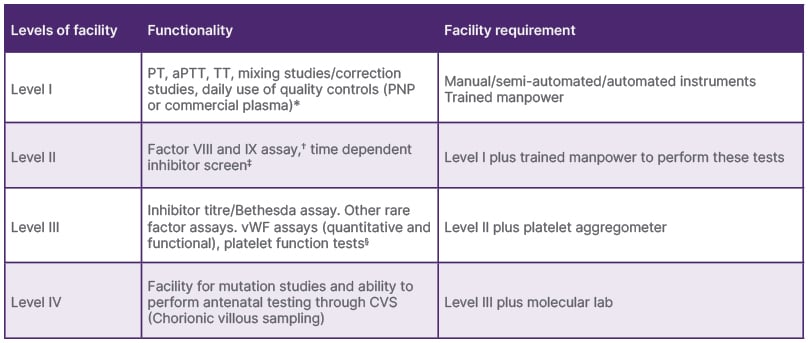

Table 3: The levels of diagnostic/laboratory services in Haemophilia Treatment Centres.

*TAT: within 3 hours.

?All routine assays should be performed at least once every 2 weeks.

‡The inhibitor screen is an aPTT-based test that evaluates the effect of mixing test plasma with control plasma after incubation for 1–2 hours. A positive inhibitor screen indicates the presence of an inhibitor and necessitates an inhibitor assay (Bethesda or Nijmegen modifications10).

§Should be able to perform in case of emergency whenever required.

aPTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; PNP: pooled normal plasma; PT: prothrombin time; TAT: turn-around-time; TT: thrombin time.

Due to the lack of availability of both clinical and laboratories services in most centres, it would be pragmatic to adopt a dichotomised approach, separating both the clinical and laboratory levels based on facility and functionality criteria. The Donabedian approach emphasises the importance of structure (facilities) and processes determining the outcomes of a service.11

The proposed stratified model addresses this by introducing a flexible, multi-tier system comprising four clinical and four laboratory levels, allowing for stepwise development and decoupling of clinical services from laboratory services. This approach facilitates gradual capacity-building, context-specific scaling of multidisciplinary care, and alignment with national priorities through KPIs, rather than centralised certification. The model promotes inclusivity, accommodates variable caseloads, and supports phased upgrades, making it better suited to diverse healthcare ecosystems, particularly in LMICs.

Incorporating clear quality improvement processes and establishing KPIs specific to clinical and laboratory services is essential for advancing haemophilia care. An evaluation framework that includes these elements will not only help monitor and assess the effectiveness of treatment, but also provide a structured path for haemophilia centres to achieve certification and accreditation. These standards act as benchmarks for care delivery, ensuring that centres meet minimum quality criteria while striving for continuous improvement. The establishment of such an evaluation framework is crucial, as it guides centres in identifying gaps in care, optimising resource use, and aligning services with international best practices. Furthermore, it empowers healthcare providers to track performance, set goals, and implement evidence-based practices, ultimately improving patient outcomes and fostering a culture of excellence in haemophilia care.

CONCLUSION

The European model of haemophilia care, structured around the EHTC and EHCCC designations, has significantly advanced comprehensive care in high-resource settings through standardised criteria such as caseload thresholds, 24-hour coverage, and full multidisciplinary teams.

However, these rigid standards may be difficult to implement in low- and middle-income countries due to disparities in infrastructure, staffing, and laboratory capabilities. In response, the proposed stratified model introduces graded levels (I–IV) for both clinical and laboratory services, enabling centres to develop progressively based on their available resources and local realities.

Unlike the centralised and prescriptive European approach, the stratified model supports flexible growth by emphasising quality improvement, institutional self-assessment, and linkage to national registries. It can incorporate KPIs aligned with the Donabedian model, evaluating structure, process, and outcome, to drive service enhancement. This context-sensitive framework empowers haemophilia centres to evolve without being penalised for not meeting uniform benchmarks, offering a practical and scalable pathway towards certification and improved patient care in diverse global settings.