THE PANDEMIC OF SOCIAL DISCONNECTION

I was working as a consultant paediatrician in the emergency department of a large children’s hospital in the Northwest of England during the COVID-19 pandemic. When the general public began to seek healthcare in person again after the various lockdowns, there were some notable differences. It wasn’t just what the patients were coming in with, such as delayed presentations of diabetes, cancers, and all forms of neglect and abuse. It wasn’t just that we were seeing an exponential increase in non-specific symptoms with no clear organic cause. It was also as if society had had an acute personality change, with increased anger, sadness, and despondence.

Users that were previously co-operative became more demanding, and incivility and abuse against frontline staff rose. We received a significant increase in the number of complaints about our clinical service. Patients and families seemed more confused, more entitled, and less grateful.

It was clear that something was wrong, but neither the service users themselves nor we as the service providers trying to help them knew exactly what. Both parties felt generally frustrated but couldn’t quite pinpoint why. Had the lockdown eroded our collective resilience? What had lockdowns and the pandemic done to society?

I didn’t realise it at the time, but what we were witnessing was not solely symptoms of poor physical health. They were not just signs of poor mental health. It was also an indication of poor social health.1 An entire primate species physically kept apart by social distancing meant that humankind was more isolated than ever before. This was a different type of public health crisis: a pandemic of disconnect.

THE MISSING PILLAR OF SOCIAL HEALTH

Social health is our ability to form and maintain positive relationships. A relationship is a connection, bond, or interaction between two or more people. Relationships can be with family, friends, neighbours, work colleagues, a partner, and so many others.2 The inaugural report of the WHO Commission on Social Connection describes social health (human connections/relationships) as the third ‘missing’ pillar of health, alongside physical health (body) and mental health (mind).2 The lockdown undoubtedly affected all three pillars, but disproportionately affected a pillar that we normally take for granted when we are not socially distanced or in full-scale lockdown.

Good social health includes positive relationships that are healthy and meaningful. Good social engagement means that we interact harmoniously with our environment, including the humans in it. Quality relationships positively affect our wellbeing, mental health, community, and sense of belonging. The skills needed to build such relationships include curiosity, empathy, adaptability, and of course, listening. Ultimately, good social health is built on quality relationships and human connection.1

In this world of great disconnect, the WHO highlights social isolation as the greatest public health challenge of our post-pandemic society.2 Loneliness is the perceived absence of social connection. Adolescents, young adults, and those over 60 years of age are at the greatest risk of loneliness. It directly affects both our physical (e.g., cardiovascular disease) and mental (e.g., depression) health. Vulnerable and marginalised groups (e.g., those with disabilities) also have higher rates of social isolation. With ever-growing remote and hybrid workforces, one in five remote workers report feeling lonely.2 How many more were not reporting their loneliness? Our unmet human need for social connection is the new public health crisis.

Whilst the pandemic was unquestionably an accelerator of social disconnection, it did not create the social health crisis. The 21st century society was already riddled with loneliness, the gradual breakdown of traditional family units and communities, and an increasing polarisation of opinion, well before COVID-19.1 However, the pandemic certainly amplified our reliance on digital technology to keep us connected during lockdowns. This will be a legacy that affects our interpersonal relationships both socially and professionally, particularly for younger generations that matured and developed during lockdowns.1

STORYTELLING FOR SOCIAL HEALTH

Much of current healthcare focuses on physical and mental health while neglecting their powerful relationship with social health. It must be made clear that these three pillars can both drive and be driven by each other.2 A deterioration in social health, as illustrated by the healthcare presentations post-lockdown, clearly impacted both physical and mental health. A significant injury (physical health) that significantly limits mobility can lead to social isolation. The stigma of depression (mental health) can lead to previously well-connected individuals becoming excluded from their social network.1

Social connection is based on having people understand you. This, in turn, gives you a sense of purpose, and ultimately, belonging. The ancient art of sharing true, personal stories is a powerful way to connect with other human beings on an emotional level. Recognising the commonalities of our lived experiences whilst celebrating our differences strengthens bonds. Storytelling could therefore be considered as one strategy to improve our social health.3

Social prescribing connects people with non-medical support through personalised activities in their local community. Prescriptions could include volunteering, art classes, or gardening.4 When it comes to connection, yoga is a way to connect with oneself, while taking a walk in a park is a way to connect with nature. Could storytelling, including the safe reflective spaces where personal stories can be shared, be included on the social prescribing list to bolster our connection with other humans?

Scandinavia was pioneering in the use of true, personal stories to build deeper human connections. The Human Library concept creates a safe space for dialogue where topics are discussed openly through stories provided by human ‘books’.5 These human books are volunteers with lived experience of a topic who can be ‘borrowed’ by readers/listeners. Listening to or ‘reading’ a human book kickstarts dialogue, which fosters social connection.6

STORYTELLING AS A DIGITAL CONNECTOR

During the pandemic, I used my skills as a Schwartz Round facilitator to create reflective spaces where healthcare staff could share stories about the social and emotional impact of their work. An online adaptation of the traditionally in-person Schwartz Rounds, ‘Team Time’, was created to support staff remotely.7 Following the pilot sessions for emergency department staff, I went on to use ‘Team Time’ to support non-clinical teams at the same children’s hospital, including the Executive Board. The shift from in-person Schwartz Rounds to virtual ‘Team Time’ seemed seismic.

The feedback from the online ‘Team Time’ sessions revealed that through sharing and listening to each other’s lived experiences, staff felt they could drop their professional mask and be their authentic selves. They could express their true emotions, be heard, and receive support and compassion from their colleagues.7 Being present and sharing stories had fostered human connection in a time of crisis and adversity when staff were, for the most part, physically separated and disconnected from their colleagues.

I applied for a wellbeing grant called ‘Perform At Your Peak’, offered through the UK’s NHS to identify the ‘energisers’ and ‘drainers’ that could be affecting employee performance. The grant provided funding for a cohort of emergency department staff to wear Firstbeat Life™ monitors (Firstbeat, Jyväskylä, Finland) used by elite athletes to identify and understand periods of stress and recovery at home and at work.8

I wore a monitor for 72 hours, which captured my heart rate, heart rate variability, and movement. These factors were then used by Firstbeat’s algorithms to determine intra-individual changes in sympathetic and parasympathetic tone. Whilst wearing the monitor, I kept a digital diary to marry the objective physiological data with the context of what I was doing at the time.

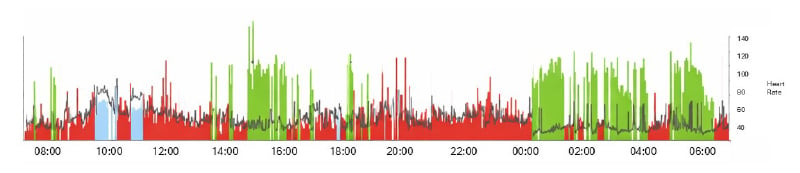

When I received my report, there was one day when I was in stress (red) mode throughout most of my working day, except for an hour between 3 pm and 4 pm when I was in recovery (green) mode (Figure 1). When the person analysing my results asked me what I had been doing during that time (i.e., a potential energiser), the answer was surprising but not surprising. I had been facilitating an online ‘Team Time’ session, listening to and amplifying the true, personal stories of my colleagues. I knew that storytelling was good for my mental health, but I had not fully recognised the impact on my physical health. Storytelling was undoubtedly improving my social health too, another example of the interconnected triangulation between the three pillars of health.

Figure 1: Physiological impact of storytelling on heart rate variability.

Firstbeat Life™ (Firstbeat, Jyväskylä, Finland) Lifestyle Assessment, personal record of author.

Is my physiological response to storytelling generalisable? A member of the emergency department admin staff, who was averse to public speaking, also happened to be wearing a Firstbeat monitor during a storytelling session. Furthermore, it was a session where they shared a personal story at the start. Right before the session and for the first 15 minutes, they were in a strong stress (red) mode. For the remaining 45 minutes, they were in a strong recovery (green) mode until the end of the session, when they returned to low-level stress (red) mode.

THE PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSE TO STORIES

The paediatrician in me has to illustrate our need for human connection using babies. The smell from a baby’s head activates the same receptors in our brain as opioid receptors. The sensation of a baby’s mouth on a nipple elicits a reflex that raises oxytocin and prolactin.1 Listening to stories can similarly impact our neural pathways and induce hormonal responses.9

The neurotransmitter dopamine is released as part of our response to an emotionally charged event. Hearing a story where there is a conflict with resolution, or where there is a recognition of a pattern, can be a powerful trigger for release. Not only does dopamine provide us with a pleasurable response, but it also activates neural pathways, which makes a story easier to remember with greater accuracy.3

When we hear about relatable characters in a story, this stimulates the release of oxytocin. This hormone increases empathy, compassion, trust, and ultimately shared emotional connection through stepping into another’s shoes.6 A listener may begin to personalise the story they are hearing, integrating their own ideas and experiences into the narrative. This process of synchronicity between storyteller and listener is called neural coupling, creating an even deeper, shared connection.10

Mirror neurons are brain cells that activate when we feel characters’ emotions and actions as if they were our own. This mirroring helps us deeply connect with the story at a motor and sensory level, turning what we are seeing and hearing into somatic ‘felt’ experiences.10 Stories of vulnerability and overcoming challenges help us process our own experiences through connecting with the journeys of others.6 Neuroscientists believe that this can be particularly helpful in carving new neural pathways to help with our post-traumatic growth.10

STORYTELLING AS A PUBLIC HEALTH INTERVENTION

From an anthropological perspective, humans need each other. We truly are social animals. Social connection is essential for health, strength, and resilience at both the micro (individual) and macro (societal) levels.4 The consequences of social disconnection are severe: reduced life expectancy, poorer cardiovascular and mental health, lower educational attainment, less productive workforces, and weaker economies. The WHO Commission on Social Connection inaugural report calls for the availability of practical and scalable solutions to strengthen social connections.2

Scaling up storytelling, as with so many public health interventions, needs a coordinated approach from how we build our physical environment (e.g., storytelling spaces in communal areas) to learning and development (e.g., more investment and availability of qualifications/apprenticeships in the humanities). Another challenge is to develop more robust methods of measuring social health.2 These are needed before we can start evaluating the societal impact of interventions such as storytelling on our human connections.It is important to acknowledge that storytelling and facilitated reflective spaces, whether in-person or online, may not be equally accessible to everyone. Within communities, there will not uncommonly be those who are in or on the border of digital poverty.2 It can also be easy to inadvertently exclude marginalised groups, such as those with hearing impairments, from storytelling exchanges without relevant targeted support such as closed captioning.

When we share our stories, we unleash a powerful symphony of neurochemistry that bonds, heals, and empowers both the storyteller and the listener.3 I feel so strongly about this power of storytelling for human connection that I have had a career pivot. I now work full-time in coaching and empowering people to share their personal stories. I also facilitate the spaces where these stories can be shared. Storytelling is my modality to promote good social health for all, but it is by no means the only approach. In addition to the other items on the menu of social prescribing that include connecting group-based activities, we also need to think about how we design and create both our physical and digital communities to unlock the power of social health across different populations.

The future may seem to be dominated by AI, but as we delegate increasing amounts of modern life to machines and computational learning, Homo sapiens need to tap into the sapiens (wisdom, knowing) that distinguishes us from our Neanderthal ancestors: complex language and abstract thinking. Stories and storytelling, capitalising on those frontal cortex functions that define our species, can guide us towards a new age of emotional intelligence. Being more aligned to our evolutionary biology in this way may be an effective and organic way to address the public health crisis of social disconnection.