INTRODUCTION

Histoplasmosis is a fungal infection caused by Histoplasma capsulatum,1-3 a dimorphic fungus1,3-6 belonging to the family Ajellomycetaceae,7 also known as Darling’s disease.4 It most frequently affects people living with HIV (PLWH).2,3,6

New hyperendemic areas have emerged in the Po River basin in Italy and various parts of India, where the prevalence of HIV among patients with histoplasmosis ranges from 2–29%.8-10 Reports from South Asia, including Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, also highlight a growing disease burden owing to improved healthcare access and diagnostics.10-12 Although globally distributed, H. capsulatum is most prevalent in Africa and the Americas.3,6,13-15 In recent years, cases have increasingly been reported in non-endemic regions, a trend attributed to enhanced diagnostic capabilities, increased physician awareness, climate change, and the global spread of HIV.8,16-18

Among PLWH in endemic areas, the annual incidence of progressive disseminated histoplasmosis is approximately 5%, with persistently high mortality despite widespread availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART).2,10,11 A USA-based retrospective study (2002–2017) revealed a 37% overall mortality among PLWH diagnosed with histoplasmosis,11,19 underscoring the critical need for timely recognition and intervention.

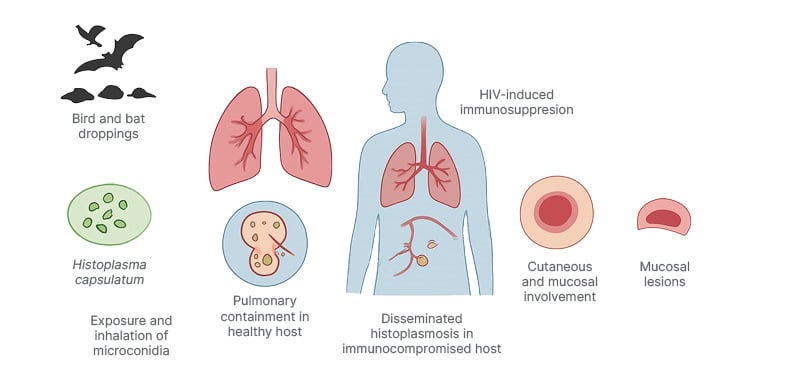

Cutaneous histoplasmosis, while infrequent, serves as a meaningful indicator of disseminated disease in patients who are immunocompromised.6,9,20 The fungus thrives in soils contaminated with avian and chiropteran excreta,7,21-25 commonly found in old buildings, caves, and humid environments. Inhaled spores are phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages, initiating infection. While healthy individuals mount an adaptive immune response that limits disease progression, PLWH lack sufficient cellular immunity, allowing for fungal proliferation and hematogenous dissemination to various organs, including the skin.

This article provides an overview of cutaneous histoplasmosis in PLWH, highlighting its occurrence in non-endemic areas and the challenges in diagnosis.

REVIEW

H. capsulatum includes human-specific variants such as H. capsulatum var. capsulatum and H. capsulatum var. duboisii, as well as recently described species like H. suramericanum and H. mississippiensis. This fungus thrives in environments such as soil contaminated with bat or bird feces, old buildings, and humid areas with high rainfall. The primary mode of entry into the host is inhalation of microconidia.1,2,7,11,22,23,25

Once inhaled, microconidia are phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages. Bats serve as primary reservoirs and dispersers of Histoplasma, although the fungus is also found in other wild and domestic animals.25-28 Climate change is expanding the geographic range of Histoplasma and its vectors, raising concerns about new endemic zones and evolving disease patterns.29-33

In immunocompetent individuals, infection is often asymptomatic or presents as self-limited pneumonia.34-38 Conversely, patients who are immunocompromised, especially those with HIV, are at higher risk for hematogenous dissemination with multi-organ involvement, including spleen, liver, bone marrow, central nervous system (CNS), and skin (Figure 1).2,3,6,8,9,15,18,19,20,35

Figure 1: Schematic overview of the pathogenesis and clinical features of cutaneous histoplasmosis in people living with HIV.

Histoplasma capsulatum spores from contaminated soil are inhaled and phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages. In immunocompetent hosts, infection remains localized, and in individuals infected by HIV, impaired cellular immunity

allows hematogenous dissemination to multiple organs, including the skin and mucous membranes. Cutaneous

lesions may present as papules, nodules, ulcers, or plaques, frequently indicating systemic disease.

CUTANEOUS MANIFESTATIONS

Cutaneous histoplasmosis occurs in 10–25% of patients with AIDS with disseminated histoplasmosis.39-41 Lesions are categorized as primary or secondary. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis is rare and results from direct inoculation of the fungus into the skin, often through trauma, leading to localized lesions such as nodules, ulcers, or verrucous plaques.6,20,36,37 Secondary cutaneous histoplasmosis occurs in up to 17% of patients with disseminated disease, particularly among individuals who are immunocompromised (e.g., those with HIV/AIDS, organ transplant recipients, or those on immunosuppressive therapy).42-45

Manifestations include generalized skin lesions such as maculopapular eruptions, nodules, plaques, ulcers, or crusted papules. These lesions are often non-pruritic but may ulcerate or become painful in chronic cases. They typically affect the face, trunk, and extremities, but can appear anywhere. Mucosal involvement (e.g., oral or nasal ulcers) often indicatessystemic dissemination.6,20,36-38,40,44-46

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis relies on histopathological examination, which typically reveals intracellular yeast forms within macrophages.6,33,39,40,45,47 Although direct microscopy or skin scraping can provide rapid preliminary information, over-reliance on these methods is discouraged due to their low specificity and potential for misidentification. Confirmatory testing using culture, histopathology, or antigen detection remains essential for accurate diagnosis. Cultures confirm the diagnosis, though results may take weeks.6,48-50 Molecular diagnostics and antigen detection, as claims, have improved sensitivity, particularly in endemic areas.50-52

Histoplasmin skin tests are available but lack specificity.15,53 Urine antigen detection is under study.54,55 Presence of cutaneous lesions in patients who are immunocompromised warrants a high index of suspicion for disseminated histoplasmosis, underscoring the importance of early diagnosis and treatment to reduce mortality.

MANAGEMENT

In patients with HIV, management of cutaneous histoplasmosis aligns with that of disseminated histoplasmosis. Treatment is generally divided into induction and maintenance phases.

• Induction therapy: for severe or disseminated histoplasmosis, especially in patients who are immunocompromised, liposomal amphotericin B is the preferred agent, and is administered intravenously at 3 (AI)–5 (AIII) mg/kg/day for 2 weeks.3,6,16,49,56-58

• Maintenance therapy: this phase aims to rapidly reduce fungal burden. When amphotericin B is not tolerated, itraconazole is used as an alternative, although it is less effective in severe cases. Standard dosing consists of 200 mg every 8 hours for the first 3 days, followed by 200 mg every 12 hours for 12 weeks.59-61 If itraconazole is not tolerated, fluconazole or posaconazole may be considered, although these agents are less potent.3,6,57,59-62

For PLWH, initiation of ART is essential to restore immune function, enhancing antifungal treatment efficacy and preventing relapse. In cases of severe inflammatory response, corticosteroids may be used temporarily alongside antifungal therapy to manage symptoms such as edema and erythema. Surgical excision may be considered for refractory or localized lesions as adjunctive therapy. Regular monitoring of fungal antigen levels (e.g., H. capsulatum polysaccharide antigen) is critical to assess treatment efficacy. Itraconazole has limited effectiveness in CNS involvement due to poor cerebrospinal fluid penetration. Suspected CNS histoplasmosis requires alternative therapeutic strategies.14,20,62

CONCLUSION

Cutaneous histoplasmosis is a frequent manifestation of disseminated disease in PLWH, signaling systemic involvement with high morbidity and mortality if untreated. Early diagnosis using histopathology, culture, and antigen detection is critical.

Treatment involves initial liposomal amphotericin B followed by prolonged itraconazole maintenance alongside timely antiretroviral therapy to restore immunity. Management of complications and monitoring of fungal antigen levels improve outcomes. With expanding geographic distribution, increased awareness and prompt intervention are essential to reduce mortality.

KEY HIGHLIGHTS

- Cutaneous histoplasmosis occurs in 10–25% of patients with HIV with disseminated disease.

- Lesions include nodules, plaques, ulcers, and maculopapular eruptions, often indicating systemic spread.

- Diagnosis relies on histopathology, culture, molecular assays, and antigen detection.

- Liposomal amphotericin B is the preferred induction therapy. Itraconazole is used for maintenance.

- ART initiation is crucial for immune recovery and treatment success.

- Itraconazole has limited efficacy in CNS involvement. Alternative treatments are necessary.

- Climate change and HIV spread are expanding histoplasmosis to new geographic areas, requiring heightened clinical awareness.