Abstract

This cross-sectional study aimed to assess the knowledge and attitudes of students at Kabul University, Afghanistan, regarding antibiotics and their use. A total of 1,073 validated self-administered questionnaires were distributed at Kabul University. The questionnaire included questions about accessibility, attitudes, effectiveness, and antibiotic resistance. Students’ knowledge levels were measured by counting correct answers and categorized into poor, medium, and high. Results showed that 81% of respondents were aware of antibiotics, and 52.1% used antibiotics only with a doctor’s prescription, but 77.2% stopped taking antibiotics once they felt better. Only 24% knew that amoxicillin is an antibiotic, and 63% had poor overall knowledge about antibiotics. The study revealed negative attitudes, many misconceptions, and insufficient knowledge among students, highlighting the need for community education campaigns at the start of each university semester to properly inform students about the proper use, effectiveness, and antibiotic resistance issues.

2. Validated self-administered questionnaires were disseminated across 22 faculties and revealed that only 24% knew that amoxicillin is an antibiotic, amongst other widespread misconceptions.

3. Nearly half of respondents accessed antibiotics without prescriptions and 44% shared them, supporting university-level education for students about the proper use, effectiveness, and antibiotic resistance issues.

INTRODUCTION

Medicines play a crucial role in healthcare by reducing illness and death from various diseases. However, when misused, they can cause harmful health effects. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than half of all medicines worldwide are either prescribed, dispensed, or used incorrectly, and half of the patients do not follow their medication properly. This issue is especially serious with antibiotics because their inappropriate and excessive use leads to antimicrobial resistance, which is rapidly increasing worldwide. Rational use of medicines means that patients receive the right medication, in the correct dose, for an appropriate period, and at the lowest cost to both themselves and the community.1-9

A lack of public knowledge about antibiotics often results in their irrational use, such as taking incorrect doses, stopping treatment early, and self-medicating. These behaviors can cause treatment failure, reduce trust in the healthcare system, and lead to adverse effects, including antibiotic resistance and gastrointestinal problems. Although healthcare providers have an important role in promoting proper use, the knowledge, attitudes, and cultural context of the community also significantly influence how antibiotics are used.10,11

There has been no previous research on the knowledge and attitudes of students toward antibiotics in Afghanistan, making this the first study of its kind in medical students. Some studies from neighboring countries show similar concerns. For example, a study in Pakistan found many students confused antibiotics with other medicines, and more than half practiced self-medication.12 Similar findings have been reported in Pakistan, where public knowledge about antibiotic use was insufficient and self-medication was common.13 In Iran, nearly 50% of students self-medicate, and only a small percentage understand the connection between improper antibiotic use and resistance.14-16 In other countries like Uzbekistan, Yemen,17 and Saudi Arabia, a large portion of people and university students use antibiotics without prescriptions and have poor knowledge about antibiotic effectiveness and resistance. These findings reveal widespread misconceptions and negative attitudes that contribute to the irrational use of antibiotics.

The WHO recommends raising public awareness and running educational campaigns as simple and effective ways to promote the rational use of antibiotics.9,18 Therefore, this study aims to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to antibiotic use among students at Kabul University, Afghanistan, to help design appropriate antibiotic education and awareness programs for them.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the knowledge and attitudes of Kabul University students regarding antibiotics. It included students from 22 faculties, divided into two groups: natural sciences and social sciences. The study took place between September 2019–December 2019.

Population and Sampling Size

The study population consisted of Kabul University students in 2019, with a total of 25,000 students that year. The sample size was calculated using Cochran’s formula, considering a p-value of 0.05 based on online data. Ultimately, the final sample included 1,073 students. The sample size for each faculty was determined, and participants were then randomly selected. A stratified random sampling technique was used. Kabul University consists of several faculties, and to ensure representation from all academic disciplines, a specific number of participants were randomly selected from each faculty. Questionnaires were distributed by trained volunteer data collectors to students in different classes and were recollected after completion. The data collected were then entered and analyzed by the research team. All Kabul University students were included, but graduated students were excluded.

Data Collection Method

The study’s purpose was explained to the respondents by volunteer data collectors. The authors developed an appropriate questionnaire by reviewing those used in previous studies. Originally in English, the questionnaire was translated into Dari, and both versions were provided. Respondents selected their answers from multiple-choice options: ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Unsure’. The questionnaire included 18 questions divided into three parts: accessibility of antibiotics, attitudes toward antibiotic use, and antibiotic efficacy and resistance.

Questionnaire Structure

The questionnaire comprised two sections. The first section collected demographic information including faculty, academic year, gender, age, and place of residence. The second section contained 17 items assessing knowledge, attitudes, and practices relating to antibiotic use. The instrument was adapted from previously used surveys in Pakistan, China, Türkiye, and Saudi Arabia, and was translated into Dari for clarity. Items covered recognition of antibiotics, sources of recommendation, self-medication, early discontinuation of treatment, preference for injectable formulations, perceptions of antibiotic strength, understanding of resistance, and awareness of correct antibiotic use. All questions were multiple-choice (‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Unsure’). Participation was voluntary, responses were anonymous, and data were used only for research purposes.

Data Analysis Method

The respondents’ answers were analyzed using the χ2 test with SPSS version 25.0 statistical software (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). P-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. Attitudes and behaviors regarding antibiotic use and resistance were evaluated by counting the correct answers from Parts 2 and 3 of the questionnaire. Each correct answer was given one point, while incorrect or unsure responses received no points. The total scores were then categorized into three groups: poor, moderate, and high.

RESULTS

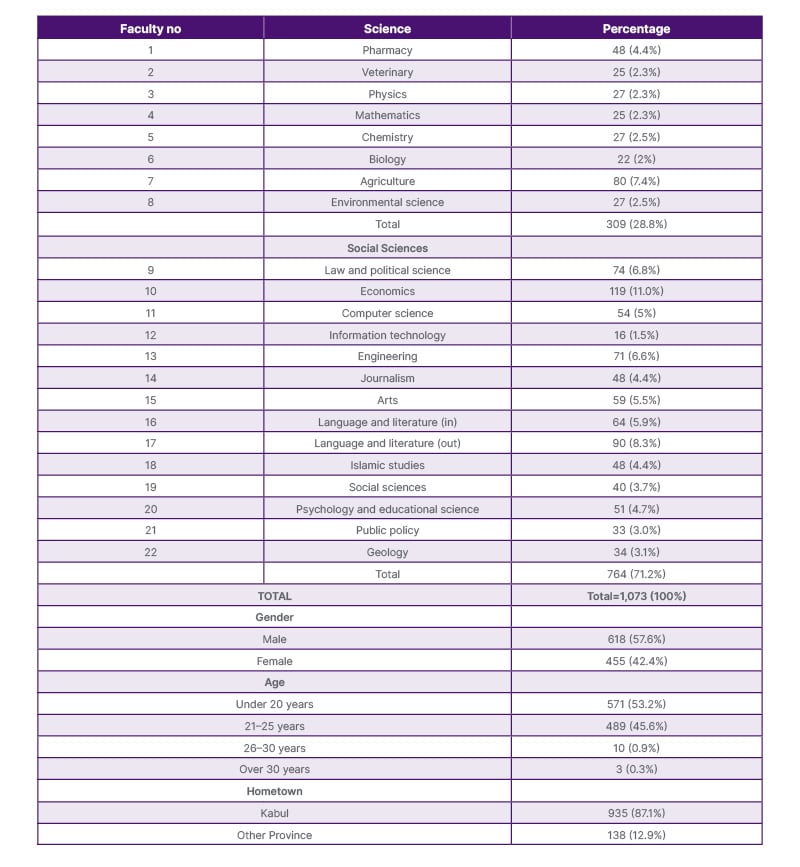

The study included 1,073 respondents, of whom 764 were from social science faculties and 309 from natural science faculties. The students’ ages were grouped into four categories: under 20 years, 20–25 years, 25–30 years, and over 30 years. Among the participants, 57.5% were male and 42.5% female (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographic properties.

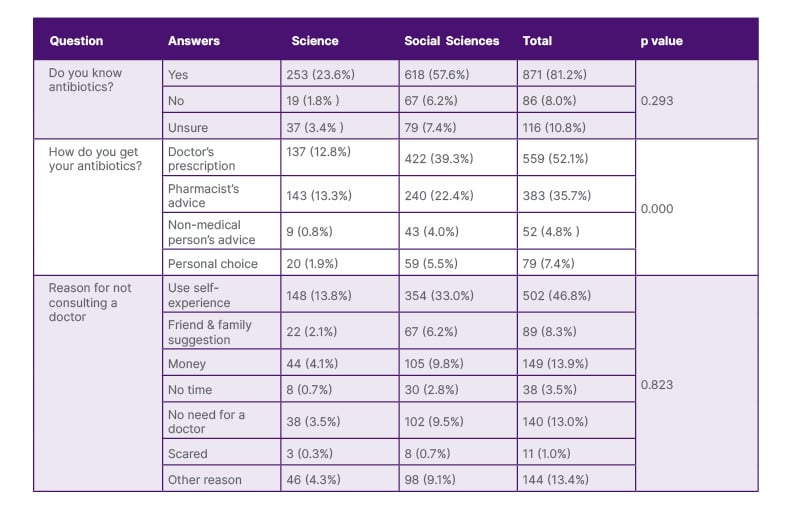

The first part of the questionnaire focused on ‘Access to antibiotics’ (Table 2). Frequency tests were performed for both the Faculty of Natural Sciences and the Faculty of Social Sciences to present the distribution of responses within each group. Additionally, an independent samples t-test was conducted to compare the mean differences between the two faculties.

Table 2: Accessibility of antibiotics.

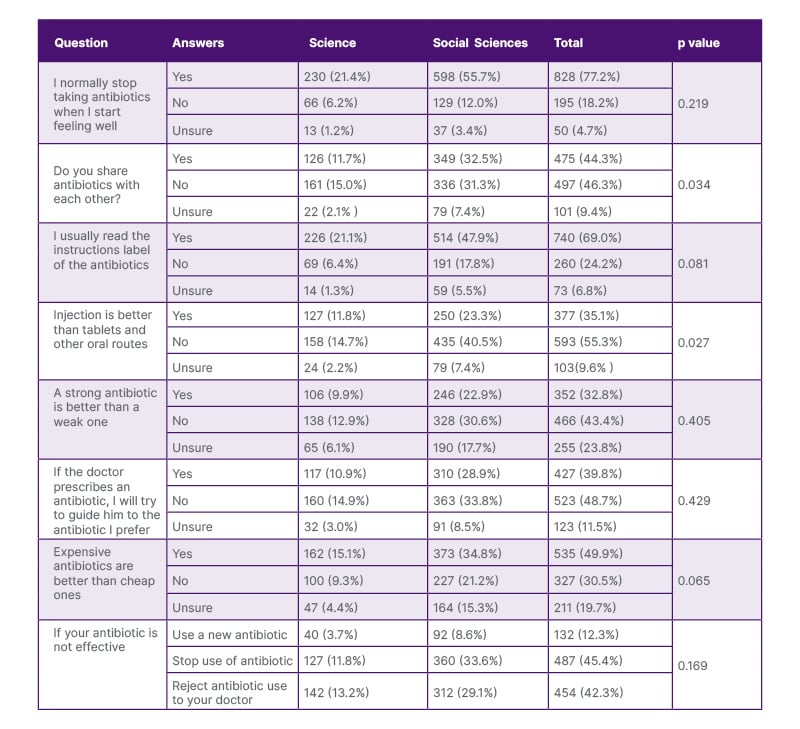

More than half of the respondents (52.1%) obtained antibiotics through a doctor’s prescription, with a significant difference between the two groups (P=0.000). Meanwhile, 46.8% relied on their own experience without consulting a doctor. Additionally, 81.2% of respondents said they knew what antibiotics are. However, 77.2% admitted to stopping antibiotic treatment once they felt better, and 44.3% reported sharing their antibiotics with others. The full percentages for this section are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3: Attitude toward the use of antibiotics.

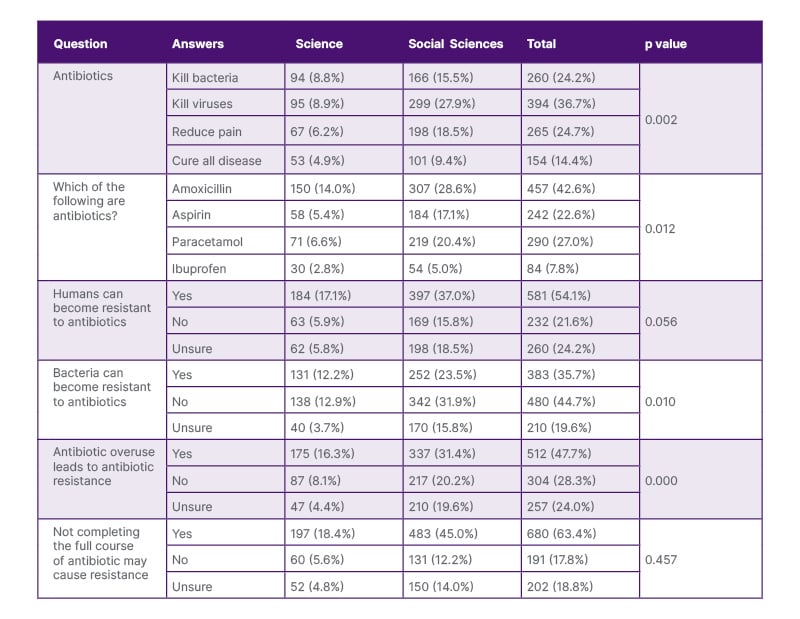

Knowledge about antibiotic efficacy and resistance was also assessed (Table 4). Only 24% correctly identified that antibiotics kill bacteria, while others thought antibiotics targeted different types of microorganisms. Also, 42% recognized amoxicillin as an antibiotic. Overall, 63% of respondents had poor knowledge scores related to antibiotic efficacy, use, and resistance. Students from the natural science faculties scored significantly higher than those from social science faculties, with this difference confirmed by an independent samples t test (p=0.000).

Table 4: Antibiotics efficacy and resistance.

DISCUSSION

There is no previous study related to the knowledge and attitudes of the public and students regarding antibiotics and their usage. The authors’ study is the first of its kind in Afghanistan in medical students. This study of different faculties at Kabul University is based on understanding the awareness of this sector of the community. Proper educational campaigns can be conducted to correct misconceptions and negative attitudes. In this study, the questionnaire was based on those used in previous studies in other countries, such as Pakistan (Karachi), China, Türkiye (Adana), and Saudi Arabia (Riyadh, Jeddah).14,15,19-22

Access to Antibiotics

In the authors’ study, 18% of participants did not know or were unsure about antibiotics. This percentage is higher than the findings reported among students in Pakistan (11%), India (4%), and Nigeria (9%),21,23,24 indicating a greater level of unawareness among the authors’ students. This result (17%) is, however, comparable to studies conducted among the general public in Pakistan.25

More than half of the respondents (52.1%) reported using antibiotics based on a doctor’s prescription. While this is encouraging, it is still lower than the 77.8% reported in a study at Riyadh University in Saudi Arabia.20 In the authors’ study, 35.5% of participants stated that they accessed antibiotics through pharmacist advice, highlighting the crucial role pharmacists play in guiding patients toward the rational use of antibiotics. In comparison, pharmacist advice was reported at 44.1% in another study20 and 39.2% in the study by Mouhieddine et al.26

The most common reason for taking antibiotics without a doctor’s prescription was self-experience (46.8%), reflecting a concerning attitude toward medicine, as people tend to rely on their previous experiences and repeatedly self-medicate. Financial problems (13.3%) and suggestions from family or friends (8.3%) were also cited as reasons. If we combine the 46.8% who used antibiotics based on self-experience with the 8.3% who followed advice from family or friends, more than half of the respondents practiced self-medication. This highlights the widespread tendency toward irrational antibiotic use. Regarding the type of antibiotic, 43% of respondents selected amoxicillin. Further details are presented in Table 2.

Attitude Toward the Use of Antibiotics

In the authors’ study, 77.2% of respondents reported that they stop taking antibiotics once they feel better. This inappropriate practice increases the risk of developing resistant bacterial strains. Unfortunately, this result is even higher than the rate reported among the general public in Pakistan (73.9%).15 Although respondents were generally aware of the emergence of bacterial resistance, the inadequate level of knowledge appears to contribute to this poor behavior. Improving awareness could lead to better antibiotic practices.

Additionally, 44% of respondents admitted to sharing antibiotics, which is another form of self-medication. The authors’ finding is consistent with that of Kerman University in Iran (45.1%), further highlighting the high prevalence of self-medication. This is a critical concern, as it can lead to serious health consequences.16

On a positive note, 69% of respondents reported reading the instructions on antibiotic labels, a higher rate than the 57% observed in a study conducted by Abu-Mostafa et al.20 in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. However, some participants mentioned that they do not read the labels because the instructions are often written in English. This underscores the importance of ensuring that antibiotic labels are written in the native language of each country, which is the responsibility of the manufacturing companies. Regarding dosage forms, 35% of respondents expressed a preference for injectable antibiotics over oral ones. This reflects a misconception, as many believe the injectable form is more effective. In reality, oral antibiotics are generally safer and more convenient. The misuse of injections can increase the risk of infections transmitted through syringes and may result in irreversible adverse effects. Encouragingly, 39% of respondents reported that they never attempt to guide doctors toward prescribing a specific antibiotic, instead relying on the physician’s judgment. This is similar to the 37% observed in Riyadh by Neda et al.20

Finally, 49.9% of respondents believed that more expensive antibiotics are more effective than cheaper ones. However, 30.4% stated that price is not related to efficacy. Research conducted by Naimi et al.27 at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Kabul University, supports the latter view, confirming that cost does not determine the effectiveness of antibiotics.

Antibiotics Efficacy and Resistance

In the authors’ first question, 81% of respondents reported that they were familiar with antibiotics. However, only 24.2% correctly identified antibiotics as drugs that kill bacteria. Alarmingly, 24.7% believed antibiotics reduce pain, while 36% thought they kill viruses. This confusion between antibiotics and painkillers may lead to inappropriate drug choices when patients suffer from pain or infection. For example, 43% of respondents selected amoxicillin as an antibiotic, which shows that while many know the name of an antibiotic, misconceptions and poor attitudes toward its use remain widespread.

Antibiotic resistance is recognized as a major public health issue. In the authors’ study, 54% of respondents believed that humans become resistant to antibiotics, whereas only 35% correctly recognized that bacteria develop resistance. This finding indicates that more than half of the respondents hold misconceptions. Furthermore, 47% agreed that antibiotic overuse contributes to resistance, which is lower than the 61.8% reported among the general public in Pakistan.15

Regarding adherence, 63% of respondents understood that not completing the full course of antibiotics may cause resistance, a result similar to that of a study among students in Riyadh (64%).20 Overall, the authors’ findings suggest that knowledge about antibiotic resistance among their participants is inadequate compared to the seriousness of the issue in this region.

Knowledge Scores

Overall, 63% of respondents demonstrated poor knowledge, 33% had moderate knowledge, and only 4% showed good knowledge. Participants from science faculties scored significantly higher in knowledge compared to those from non-science backgrounds. This difference can be attributed to the greater exposure of students in faculties such as Pharmacy and Biology, where education provides them with a deeper understanding of microorganisms and related subjects.

CONCLUSION

According to the results of this study, Kabul University students exhibited a negative attitude toward antibiotic use, marked by many misconceptions and poor knowledge. Therefore, it is essential to conduct awareness campaigns to promote the rational use of antibiotics. As the first study of its kind in Afghanistan involving medical students, the authors recommend that similar research be carried out in other educational settings, such as schools, to further enrich our understanding. Additionally, community awareness campaigns should be launched at the start of each university semester to educate students about the appropriate use of antibiotics and the risks of resistance. Pharmacists and other healthcare professionals should actively participate in patient education. Increasing understanding of complications like antibiotic resistance may motivate individuals to change harmful behaviors.