Abstract

Introduction and Objectives: There is increasing evidence suggesting the impact of human gut microbiota on digestion and metabolism. It is hypothesized that the microbiome in people who are obese is more efficient than that in people who are lean in absorbing energy from food, thus predisposing them to weight gain. A transformation in gut microbiota has been demonstrated in patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, which has been positively associated with post-surgical weight loss. However, there is a lack of studies investigating the impact of probiotics on weight loss in post-bariatric surgery patients. The authors conducted a pilot clinical trial to investigate the impact of a probiotic, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG), on weight loss and quality of life in patients who have undergone bariatric surgery.

Methods: The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01870544. Participants were randomized to receive either LGG or placebo capsules. Percent total weight loss at their post-operative visits was calculated, and differences between the two groups were tested using a t-test with unequal variances. The effect of LGG on Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) scores was estimated using a mixed model for repeated measures.

Results: The mean rate of change in percent total weight loss at post-operative visit 1 for the placebo and treatment groups was 0.098 and 0.079 (p=0.41), respectively, whereas that at post-operative visit 2 was 0.148 and 0.126 (p=0.18), respectively. The difference in GIQLI scores on 30-day and 90-day visits was 0.5 (-7.1–8.0), p=0.91, and 3.7 (-4.9–12.3), p=0.42, respectively. LGG was recovered from the stools of three out of five participants in the treatment group.

Conclusion: The authors did not appreciate a significant difference in the mean rate of weight loss or GIQLI scores between the groups that received LGG versus placebo. This study demonstrated the survival of Lactobacillus during transit through the gastrointestinal tract.

Key Points

1. Bariatric surgery transforms gut microbiota and drives weight loss, but whether probiotics improve outcomes remains uncertain; clinicians ask if Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) could enhance postoperative weight or quality of life.2. This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial enrolled post-bariatric patients to receive LGG or placebo for 44 days, assessing total weight loss, Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) scores, safety, and stool recovery of LGG.

3. LGG did not significantly change weight loss or GIQLI versus placebo; recovery in three of five stools confirms survival. Probiotics to accelerate weight loss appear unwarranted, pending larger, longer-duration studies.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a major public health problem worldwide. In the USA, 66% of the population is classified as overweight or obese.1

The ‘microbiome revolution’ has, in the last 20 years, brought our attention to the importance of human gut microbiota as a factor affecting health and disease.2 Gut microbiota include a range of microorganisms that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract and have been implicated in digestion and metabolism, protection from pathogens, insulin resistance, and neurologic functioning.3-7 Metagenomics and twin studies have revealed that certain microbial compositions are associated with lean body composition, and alteration of these microbial communities is associated with weight gain and metabolic disease.8,9 In people with obesity, the flora of the gut has been found to be less diverse, less rich, and to have an increased ratio of Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes as compared to normal weight individuals.10 It is hypothesized that the obese microbiome is more efficient than the lean microbiome in absorbing energy from food, thus predisposing to weight gain.8

Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for the achievement of prolonged weight loss and has been associated with improvement in diabetes and hypertension.11,12 Studies suggest that the beneficial health effects of these surgeries are not only explained by procedure-induced food restriction and malabsorption but also by alterations of neuroendocrine and immune signaling pathways.13 An increase in Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria with a decrease in Firmicutes after bariatric surgery has been demonstrated. When the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio after bariatric procedures was used as a surrogate marker for the observed changes in the obese microbiome compared to the lean microbiome, it was positively associated with post-surgical weight loss.14

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) is a widely studied probiotic, especially with regard to its influence on metabolic syndrome. The authors chose the LGG strain because, compared to other strains, it demonstrated the fastest growth while also being stable in stomach acid and bile, capable of surviving the upper gastrointestinal tract to reach the colon, adhering well to intestinal epithelial cells, and producing antimicrobial substances active against various pathogenic and commensal gastrointestinal bacteria.15 A favorable impact on obesity and diabetes has been demonstrated in mice with diet-induced obesity, showing evidence of improvement in insulin resistance with LGG.16,17

Whereas there is increasing evidence to suggest that use of probiotics is linked with lower inflammatory state and weight loss, there is a lack of studies investigating the impact of probiotics on weight loss in patients who have undergone bariatric surgery.18-20

To inform future studies, the authors conducted a pilot trial to investigate the impact of LGG on weight loss in patients who have undergone bariatric surgery.

METHODS

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial to investigate whether weight loss and changes in quality of life differ after bariatric surgery in patients who did and did not receive LGG. The primary outcome is the rate of change of percent total weight loss. Secondary outcomes are the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) on the day of surgery, at post-operative visit 1 and visit 2, adverse event percentages, and recovery of LGG from stool.

Study Population

Participants were recruited from Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, USA, from June 24, 2013–January 31, 2016, if they were scheduled for elective gastric surgery for weight reduction. Patients were eligible for the study if they were at least 18 years of age, were evaluated for surgery as outpatients, and had stable comorbidities. Exclusion criteria included active colitis; recent or planned receipt of radiation or chemotherapy; being on active immunosuppressive medication; known or suspected allergies to probiotics, lactobacillus, milk protein, or microcrystalline cellulose, or allergy to two or more of the rescue antibiotics that might be used to treat Lactobacillus infection (ampicillin, clindamycin, and moxifloxacin) should that become necessary; and positive baseline stool culture for LGG.

Participants included in the study were restricted from consuming certain yogurt; however, since yogurt is a dietary staple after bariatric surgery, to improve enrollment after initial slow accrual, the protocol was later amended to allow for types of yogurts that contained select live cultures that would be expected to have minimal effect on patients’ microbiota, as well as yogurt without cultures. Four commercially available yogurts were permitted.

Patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy were initially planned to be excluded from the study. However, sleeve gastrectomy rapidly became the preferred weight-loss surgery, which resulted in significantly fewer gastric bypass surgeries at xxx Medical Center than at the time of initial study design. Therefore, in order to improve enrollment, the study design was amended to include patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy, in addition to gastric bypass surgery.

Trial Design and Oversight

The trial design is parallel with an allocation ratio of 1:1. Sample size analysis was not conducted since this was a pilot study to inform a future larger-scale trial.21

The random allocation was done by the statistician using a random number generator with the allocation sequence provided directly to the research pharmacy, which labeled the pills with the subject names but without identification of the compound. Study staff, which included investigators and research assistants, enrolled participants and went to the research pharmacy to pick up the study compound already labeled for the subject. Thus, investigators, study staff, and participants were blinded, as were the clinical staff caring for these participants.

Participants were randomized to receive either probiotic capsules of LGG (1×1010 organisms per capsule) or identical appearing placebo capsules provided by Martek Biosciences Corporation (Columbia, Maryland, USA), manufactured by Chr Hansen, Inc. (Hørsholm, Denmark), to be taken twice daily for 44 days, beginning 14 days before surgery. Pill bottles contained 100 capsules. Capsules were collected from each subject prior to initiation of the course and at study completion. One capsule from each time period was cultured to confirm the viability of the organism and organism counts. Ten extra capsules were provided in case of loss of capsules. Remaining capsules were counted at the end of the study period to assess adherence. Stool samples were obtained at baseline (2–4 weeks before surgery), on the day of surgery, and at post-operative visit 1 and post-operative visit 2 to assess for the presence of colonization by LGG.

To monitor for adverse events, participants completed questionnaires about the presence or absence of certain symptoms before and after they began taking the study compound. These questionnaires were completed at the first surgeon visit, first pre-operative visit, and day of surgery in order to establish a baseline, then at the first four weekly post-operative telephone check-ins, and post-operative visit 1 and 2.

All participants received routine pre-operative prophylactic antibiotics to prevent surgical site infection. One subject in the placebo group was receiving azithromycin pre-operatively for suspected bacterial infection and continued it for several days after surgery.

The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01870544, and was approved by the xxx Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was taken from all participants. CONSORT reporting guidelines were used (Supplement Table 1; Appendix 1).22

Data Collection

Demographic information, history of chronic diseases, and medications were collected at screening. Participants were asked to complete the validated GIQLI questionnaire at the pre-operative visit, on the day of surgery, and at post-operative visit 1 and visit 2.23 Study weight measurements were taken at the preoperative visit, the day of surgery, and at post-operative visit 1 and visit 2. Weights were also extracted from the electronic medical record when available from visits not part of the study.

Statistical Analysis of Clinical Outcomes

Compared to other metrics such as excess weight loss and change in BMI, percent total weight loss (%TWL) has been found to have the least variability when stratified by preoperative patient characteristics, and therefore, is the metric used in this study.24 Subject weights were measured during post-operative visits. Percent total weight loss at X days (%TWL_X) was calculated as (weight at surgery – weight at visit)/weight at surgery x X/(delta day), where delta day was the difference in days between the date of surgery and the date of visit. Differences in %TWL_X between the two groups were tested using a t-test with unequal variances.

Sample Collection

Participants were given stool collection kits consisting of a toilet hat, gloves, tongue depressors, specimen cups, and paper bags, and asked to produce and save a stool sample in their freezer within 24 hours of their appointment date and to bring the sample to their scheduled visit. Samples were then aliquoted and frozen at –80 °C.Isolation of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG from Capsule and Stool Samples Stool samples and capsules were serially diluted and plated in duplicate onto Lactobacilli selective agar supplemented with tomato juice and glacial acetic acid. Plates were incubated for 48 hours in an anaerobic chamber (5%CO2, 10%H2, 85% N2) at 35 +/- 2 oC and were then observed for characteristic growth and colonial morphology. Presumptive LGG colonies, appearing as white and creamy with a distinct buttery smell, were enumerated. The palisading appearance of LGG colonies on Gram stain was used to distinguish it from other Lactobacillus species. All strains presumptively identified were run through the APIZYM® (Biomerieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France), an identification kit that differentiates between the Lactobacillus species on the basis of enzymatic reactions. Isolates that were consistent with LGG by APIZYM® were additionally run through the API CH-50® (Biomerieux) system, which differentiates between different species of Lactobacillus on the basis of carbohydrate fermentation.

Statistical Analysis of Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) Scores

The effect of LGG on the continuous GIQLI scores was estimated using a mixed model for repeated measures. The outcome for each subject consisted of all follow-up measurements, including the baseline measurement. All variables included in the model were treated as fixed effects, and included categorical time, randomization, and their interaction. The authors performed sensitivity analyses to account for missing data in follow-up using pattern mixture models (PMM). They used the core functionality available in SAS PROC MI and MIANALYZE procedures to implement two types of PMM: standard PMM and control-based PMM.

RESULTS

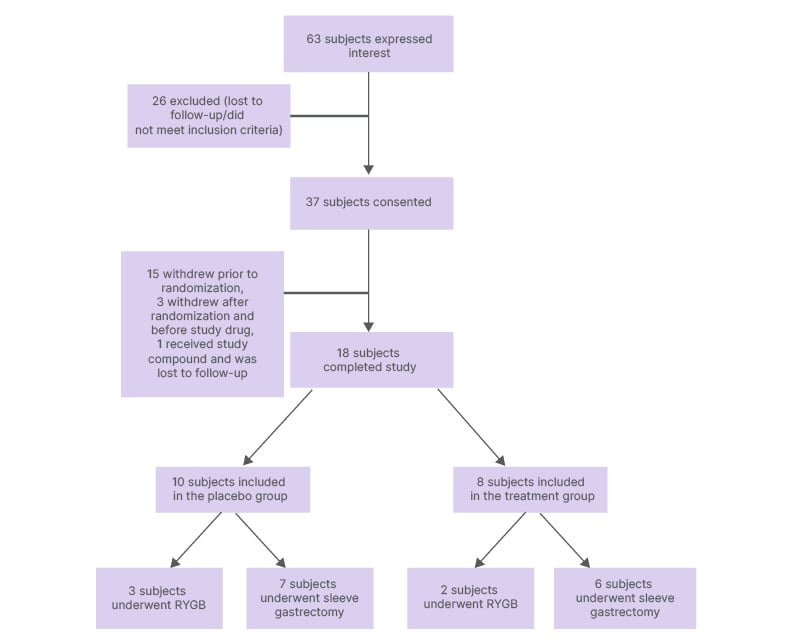

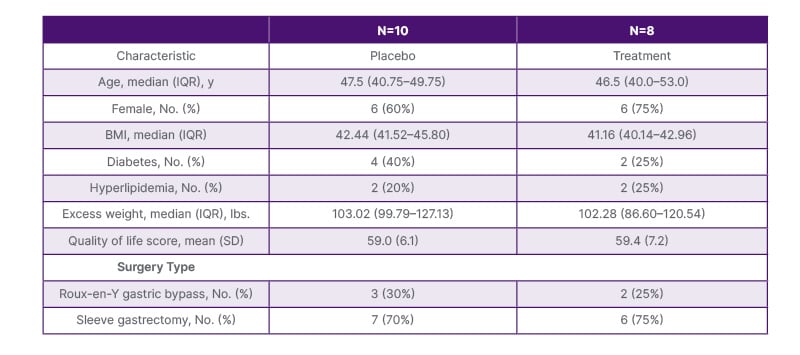

A total of 37 bariatric surgery candidates were recruited and followed up through April 2016. Of these, 15 participants withdrew prior to randomization, three after randomization and before study drug was administered, and one received the study drug but was lost to follow-up, with 18 participants completing follow-up (Figure 1). Ten participants received oral placebo, and eight received oral LGG. Table 1 compares the characteristics of participants by study group. The median age of the placebo group and the treatment group was 47.5 and 46.5, respectively. Out of 18 participants, 12 were female, comprising 60% of the placebo group and 75% of the treatment group. Of those who received LGG, compliance was variable: in the treatment group, the median of doses missed was 5.5 (interquartile range: 0–9), and that in the placebo group was 3 (interquartile range: 0–19). Baseline median BMI and excess weight of the placebo group (42.44 and 103.02 lbs, respectively) were comparable to the baseline median BMI and excess weight of the treatment group (41.16 and 102.28 lbs). The placebo group, as compared to the treatment group, had a higher percentage of patients with diabetes (40% versus 25%, respectively) and a lower percentage of patients with hyperlipidemia (20% versus 25%, respectively). Most participants underwent sleeve gastrectomy (70% and 75% for placebo and treatment groups, respectively) while the rest underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Figure 1: Flowchart of subject selection.

RYGB: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Table 1: Characteristics of the study population.

IQR: interquartile range.

At baseline, mean (SD) GIQLI scores for treatment and placebo groups were 59.0 (6.1) and 59.4 (7.2), respectively. On the day of surgery, the GIQLI score was 61.1 (6.3) for the treatment group, as compared to 57.4 (9.2) for the placebo group, with a mean difference (95% CI) of 3.7 (–3.8–11.2), p=0.35. At post-operative visit 1, the GIQLI score was 55.1 (8.5) for the treatment group, as compared to 55.5 (4.0) for the placebo group, with a difference of 0.5 (–7.1–8.0), p=0.91. At post-operative visit 2, the GIQLI score was 60.7 (4.9) for the treatment group, as compared to 56.5 (6.8) for the placebo group, with a difference of 3.7 (–4.9–12.3), p=0.42.

The mean time between surgery and post-operative visit 1 for the treatment and placebo groups was 34 and 54 days, with a median of 38 and 48 days, respectively. The mean time between surgery and post-operative visit 2 for the treatment and placebo groups was 105 and 125 days, with a median of 107 and 111 days, respectively. The mean rate of change in %TWL at post-operative visit 1 for the placebo and treatment groups was 0.098 and 0.079 (p=0.41), respectively, whereas that at the post-operative visit 2 was 0.148 and 0.126 (p=0.18), respectively.

LGG was not recovered from any stool samples from participants belonging to the placebo group. Among participants in the treatment group, no samples were successfully obtained after completion of the course of treatment. All samples were taken during the treatment course. Stool samples were collected from only five of the eight participants in the treatment group after the start of the course of treatment. Of the five, LGG was recovered from the stool samples of three participants. One of the participants from whom LGG was not recovered was later found to have missed 19 doses, and the other four doses.

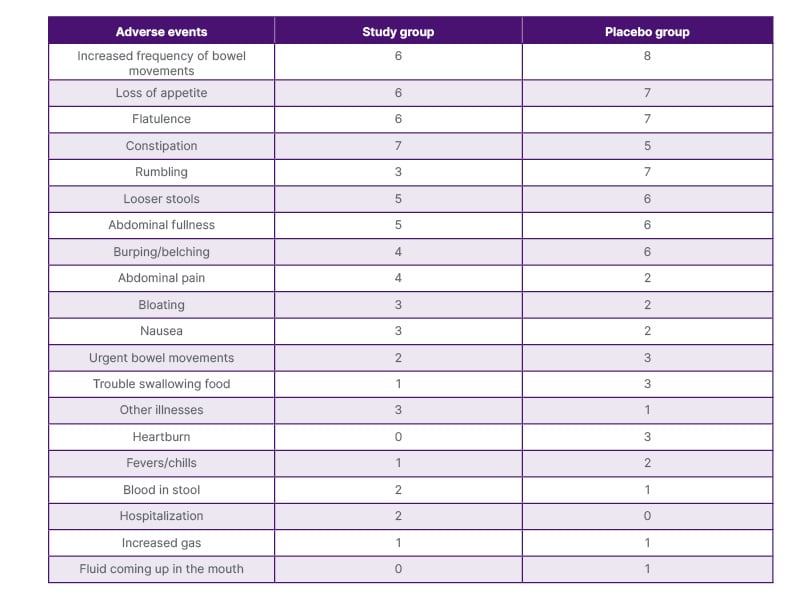

The most common adverse events experienced by the study and placebo groups while taking the study compound were increased frequency of bowel movements, loss in appetite, flatulence, constipation, rumbling, looser stools, and abdominal fullness (Table 2).

Table 2: Adverse events reported by participants while taking the study compound.

DISCUSSION

In the authors’ pilot study of patients who underwent bariatric surgery, they did not appreciate a clinical or statistically significant difference in the mean rate of weight loss between the groups who received LGG versus placebo. Their study findings are consistent with results demonstrated by a systematic review and meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials, including a total of 279 patients after bariatric surgery, in which no significant difference in percent excess weight loss at 3 months, change in BMI, waist circumference change, or fat mass change was noted between the probiotic and placebo groups.25 However, it should be noted that if there were some minor impact of oral probiotics on weight loss, this may be masked by the substantial effect of bariatric surgery on weight loss, resulting in no measurable difference between the two groups.

This is the first study, to the authors’ knowledge, to evaluate whether probiotics can be recovered in the stool of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery. To exert its beneficial properties, probiotics must survive during their transit through the low pH environment of the stomach and the lytic enzymes present in the small intestine. In the authors’ study, LGG was recovered from three of the five participants in the treatment group, demonstrating survival, though inconsistent, of the Lactobacillus during transit through the gastrointestinal tract. Several factors may have contributed to the lack of recovery of LGG from two participants in the treatment group who were still in the treatment phase, including adherence, the constituents of the participants’ diet, which can affect survival and growth of the bacteria, the stability of the culture, and the size of the inoculum, which affects the survival of probiotic bacteria.

There was no significant difference in the GIQLI scores within the follow-up period between the study and placebo groups.

In the authors’ pilot study of patients undergoing bariatric surgery, LGG was found to be safe. Adverse event rates were similar in the two groups and consistent with what would be expected in patients who have undergone gastrointestinal surgery.

Growing evidence supports that weightloss interventions, whether dietary or surgical, lead to changes in the composition of the gastrointestinal microbiome.26 However, there are conflicting data regarding the impact of probiotics on weight loss. Whereas Kadooka et al.27 demonstrated a significant decrease in weight and body fat in participants who received fermented milk with Lactobacillus compared to a control group. A meta-analysis by Mohammadi et al.28 of nine RCTs, including 410 participants, showed no significant difference in BMI or percentage of excess weightloss between the probiotic and control groups.28

The authors study had several limitations. It was a pilot study and, therefore, not intended to be fully powered to detect statistically significant differences in outcomes between groups. Though the follow-up outpatient visits were intended to be at 1 and 3 months post-surgery, there was significant variability in the number of days after surgery at which participants were evaluated. The 3-month duration of follow-up may not have been long enough to demonstrate a clinically significant difference in weight loss or quality of life scores between the two groups.

Future trials should investigate approaches to enhance LGG colonization, including the use of higher probiotic doses, evaluation of alternative or complementary strains, and optimization of delivery methods such as sustained-release formulations or co-administration with prebiotics to improve bacterial survival and engraftment in the gastrointestinal tract.