Interview Summary

In this patient-focused interview, EMJ spoke to Jean-Philippe Plançon, a patient with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) and the current President of the European Patients Organization for Dysimmune & Inflammatory Neuropathies (EPODIN). Plançon has lived with CIDP for 25 years and, in his role as patient advocate, acts as a voice for patients with CIDP and other immune-mediated peripheral neuropathies at the European level.INTRODUCTION

CIDP is a rare, progressive, immune-mediated neurological disorder characterised by limb weakness. It can lead to functional disability or sensory deficits, with patients often reporting problems with mobility, balance, fatigue, and pain. As a result, CIDP is associated with a substantial clinical burden, impacting patients’ daily activities, work productivity, and health-related quality of life.1-5

JOURNEY TO DIAGNOSIS

Plançon described how he was first diagnosed with CIDP at 30 years old while working as a registered nurse in the ICU: “The initial symptom was that I lost the ability to use my left arm and I’m left-handed.” A lumbar puncture proved negative, and at that point in time “no further attempt was made to dig deep into the diagnosis, so life restarted more or less normally,” he explained.

However, several months later, Plançon began experiencing paraesthesia and was referred to a neurologist who suspected some type of peripheral neuropathy. “That was the entry for me into the disease, and [a] few months after I had the precise diagnosis of CIDP,” he explained. “However, even as a registered nurse, I didn’t understand. If a doctor says you have breast or prostate cancer, it’s terrible of course, but it generates some images in your head, whereas I had nothing to work with.”

Describing his emotional response to the diagnosis, Plançon confessed that: “The beginning of the disease was difficult. I struggled to accept I had CIDP, and felt angry sometimes. This is a process akin to losing someone you love. I loved the 30-year-old young man that I was, and I had to learn to lose this image.”

In terms of the diagnostic journey, Plançon described himself as “pretty lucky” to have received a relatively quick diagnosis. “It was evident from the fact that I couldn’t feel my fingers that it was something neurological, so it was a more typical presentation,” he explained. “If you consider the first acute symptoms to the diagnosis itself, it probably took 2 years.”

Real-world evidence shows that CIDP is often associated with an extended time to diagnosis, with over one-third of patients initially misdiagnosed.2 “Mine is not the worst story that I’ve heard,” Plançon confirmed. “For other patients, the diagnostic journey can be much longer, it can take 10 or even 15 years.”

IMPACTS ON DAILY LIFE AND WORK

“As a nurse, I needed my hands for very technical procedures in the ICU, so I decided to be proactive and change my work, becoming a healthcare manager and, after that, a teacher in a high school. The CIDP pushed me to change; I had to rethink my entire life,” Plançon explained.

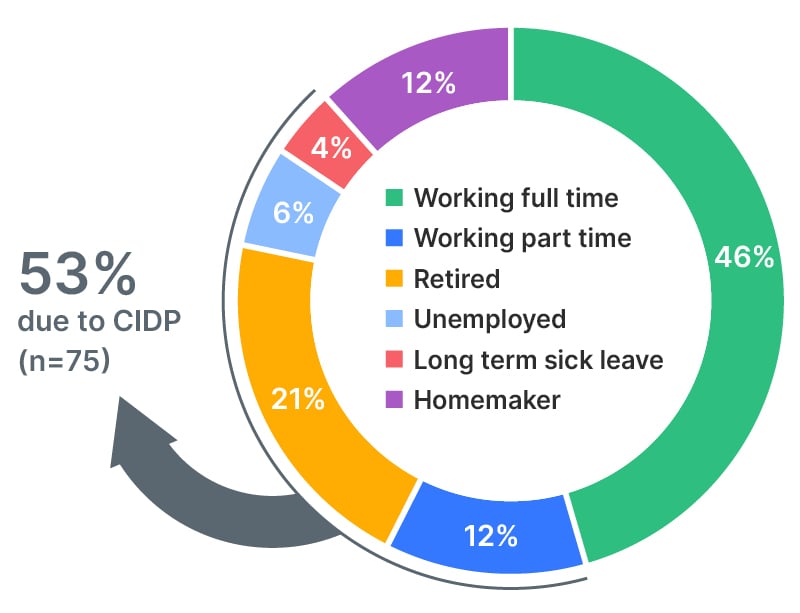

He confirmed that, for many patients with CIDP, the diagnosis leads to a decrease in productivity, and this depends on the severity and burden of the disease, availability/access to therapies, and the support and care provided by the health and social care system. “Sometimes you have to step back to be treated because you’re tired or because you’re too ill to work,” he noted. This impact on productivity is also reflected in real-world surveys, where CIDP has been shown to substantially affect patients’ employment, often hindering or completely preventing them from working.5 Many patients with CIDP are unemployed, retired, on long-term sick leave, or are working part time, with 53% citing CIDP as the key reason (Figure 1).2

Figure 1: Employment status (% of patients).

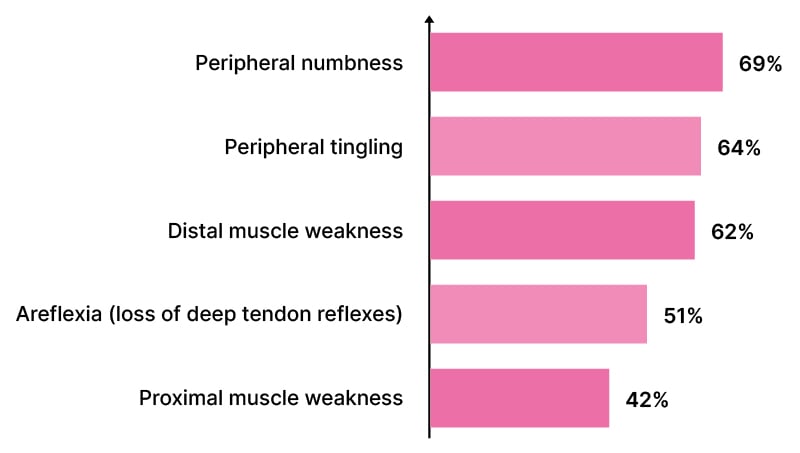

Fortunately, Plançon responded positively to treatment with polyvalent immunoglobulin therapy, so his physical function has been more or less preserved. “I still have now some persistent symptoms, mainly weakness in my left hand, which can lead to difficulty doing usual daily things like writing, shaving, and doing up buttons,” he acknowledged. He also described some gait issues and impaired balance, and noted that “it’s always a little bit painful”. Plançon’s experience resonates with the wider CIDP community, where around half of all patients reported experiencing moderate-to-severe symptoms, despite many receiving treatment (Figure 2).2 As a consequence, 47% of patients rely on one or more mobility aids, most commonly canes or walking sticks.2

Figure 2: Top five symptoms (% of patients).3

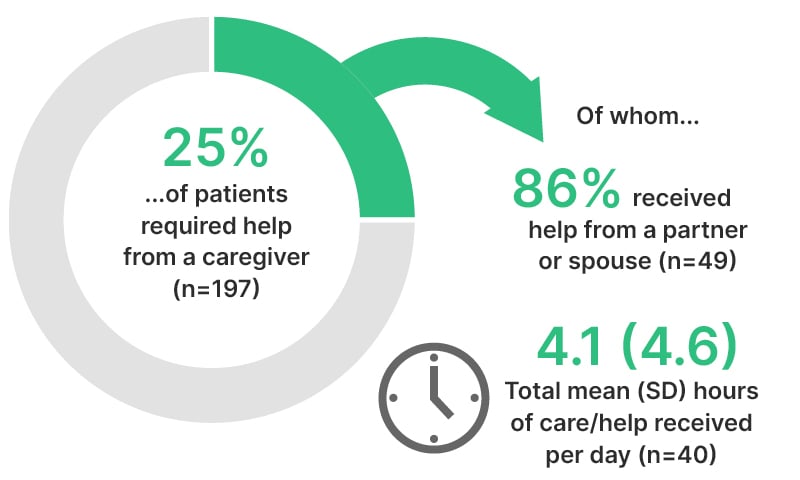

Plançon’s wife has been his main pillar of support in the 20 years since diagnosis, and he confirmed that CIDP can place a burden on both caregivers and wider family members. Real-world surveys have shown that over a quarter of patients with CIDP require assistance from a caregiver, and in many cases, this can have a reciprocal impact on the latter’s ability to work (Figure 3).2,4 Plançon explained that this impact on caregivers depends on the severity of the CIDP and the patient’s level of disability, as well as their overall ability to cope with the disease. He pointed out: “Someone in a wheelchair has to cope differently than someone like me on his own two feet and generally autonomous, so the burden is less.”

Figure 3: The caregiver burden in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy.3

EMOTIONAL ASPECTS

In terms of the impact of CIDP on health and emotional well-being, Plançon said this was most pronounced at the beginning of the disease. “One of the very difficult things with the CIDP is you can’t predict the evolution of the disease. My wife was pregnant, I was 30, and I didn’t know what would happen to me nor my baby: if I was going to die, be in a wheelchair, [or] whether my baby was going to inherit the same disease. It was very complicated at that moment. In reality, to my knowledge CIDP has not been shown to have any impact on patient mortality, nor is it an inherited condition.”6

Surveys have shown that up to 24% of patients with CIDP are dealing with concomitant depression and anxiety, and that these psychological comorbidities are closely linked to symptom severity.2 Plançon added that how patients are affected psychologically by CIDP is very individualised. “Of course, there is a huge impact on your life,” Plançon acknowledged, “but it also depends on patient factors such as age, if they live alone, have family, or are in a lot of pain.”

After his diagnosis, Plançon described how, “psychologically speaking, I went from being a young man who was very sporty to a person with a chronic disease. What I didn’t realise at first was the ‘C’ of CIDP. It took a long time to really understand that the chronic nature of the disease meant I would have to live with it my entire life.”

SUPPORT AND UNMET NEEDS

Continuing on this subject, Plançon said he had received very little ongoing support from healthcare professionals (HCP) during his CIDP journey, and attributed this mainly to short consultation times and infrequent visits. Now, for example, he only sees a neurologist once every year for routine tests and follow-up. “I don’t mean there is no support, I’m just not sure it’s the role of a neurologist to provide it,” he clarified. “My expectation is for a neurologist to be an expert in the disease. Of course, I expect them to understand my needs, but the main thing is to be able to refer patients to extra support in the form, for example, of psychologists and physiotherapists as required.”

Some analysis of medical and non-medical resources required by patients with CIDP showed that the mean number of HCP types involved in disease management was only 2.4. Patients most often saw a neurologist (81%), followed by a physical therapist (41%), and a family doctor/general practitioner (38%).4 “The problem is we are talking here about a rare disease. This means there is little knowledge of the disease and few HCPs with professional expertise in CIDP,” Plançon noted.

Plançon stressed that there are “many unmet needs” within existing care pathways for CIDP. Particularly at the time of diagnosis, he emphasised the importance of ensuring patients fully understand the disease and its management, as unanswered questions can lead to anxiety. Ideally, additional support and education should be provided by a dedicated nurse or team, and follow-up should be with the same neurologist in order for “patients to build a relationship with their clinician.”

EDUCATING PATIENTS AND RAISING AWARENESS

Plançon stressed that the most important step for those newly diagnosed with CIDP is to engage with their local patient organisation, or other local patient groups, who can support them in understanding and accepting their diagnosis. “I’ve heard the same questions for 20 years: what will happen tomorrow? How is CIDP going to impact my daily life? Is there any treatment able to cure me?”

“These are complex questions with no clear answers,” he continued, “so the best way we can support patients is to outline the state of play in CIDP: this is what we know, and this is what we don’t know. This will avoid patients seeking information from inaccurate sources or looking for a ‘magic pill’ to treat the condition.”

Moving forward, Plançon highlighted the importance of increasing understanding and raising awareness of CIDP, because the “invisible symptoms” mean the condition is often overlooked. “If we met tomorrow, you would just see a normal man,” he pointed out. The recent ‘Dare to Care’ webinar series developed by argenx (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) is one such measure, designed to help bring the patients’ perspective into focus and raise awareness among HCPs of the impact and everyday reality of living with CIDP.7 This platform brings together patients, caregivers, and experts to share experiences, explore real-world data, and foster meaningful discussions around CIDP.7

HOPES FOR THE FUTURE

Looking ahead, Plançon highlighted the need for more investment in fundamental CIDP research in the hope that this will lead to new treatment options for patients. He also emphasised the need to adopt a more integrative view of health in patients with CIDP. “It would be much more powerful if we were considered in a broader, integrative, and more holistic way,” Plançon concluded.

EU-EFG-25-00032 | July 2025