Abstract

Background: Spontaneous pneumomediastinum is an uncommon cause of chest pain and breathlessness, often seen in young adults with asthma. Its symptoms may mimic asthma exacerbations or chest infections, leading to a diagnostic delay.

Case Presentation: The author reports the case of a 30-year-old man with asthma who initially presented to an out-of-hours service with cough, sputum, and shortness of breath. He was treated for a chest infection, but subsequently developed pleuritic chest pain and worsening breathlessness. On arrival at the emergency department, he was tachypnoeic with palpable neck crepitus. Chest X-ray and CT thorax confirmed pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema, and a small apical pneumothorax.

Management and Outcomes: The patient was admitted under the cardiothoracic team and managed conservatively with O2, bronchodilators, and corticosteroids. A chest tube was not required as the pneumothorax was small and stable. He was discharged after 3 days, with complete radiological resolution at 2 weeks and no recurrence.

Conclusion: Spontaneous pneumomediastinum should be considered in young adults with asthma presenting with acute chest pain and breathlessness. Clinical examination and imaging are essential for diagnosis, and most cases resolve with supportive treatment. Increased awareness can prevent unnecessary antibiotics or invasive interventions.

Key Points

1. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum is a rare cause of chest pain and breathlessness in patients with asthma. Increased awareness of this condition can improve diagnostic accuracy and prevent inappropriate treatments, such as unnecessary antibiotics or invasive procedures.2. Clinical examination remains essential. In this case, neck crepitus on palpation prompted early imaging. CT thorax confirmed the diagnosis and ruled out life-threatening complications, such as Boerhaave syndrome.

3. Most cases of spontaneous pneumomediastinum resolve with supportive management alone. This case highlights that careful inpatient monitoring, patient education, and planned outpatient follow-up are important components of optimal care to ensure complete recovery.

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) refers to the presence of free air in the mediastinum without preceding trauma or iatrogenic cause. It is uncommon, with an estimated incidence ranging from one in 14,000 to one in 25,000 emergency presentations, and is particularly associated with young adult males and patients with underlying lung disease, such as asthma.1,2 The mechanism is explained by the Macklin effect, whereby alveolar rupture secondary to sudden rises in intrathoracic pressure results in air dissecting along bronchovascular sheaths into the mediastinum.3 Clinical manifestations are often non-specific, overlapping with asthma exacerbations, chest infection, or cardiac conditions, making diagnosis challenging.

Here, the author presents a case of SPM in a young man with asthma, initially misdiagnosed as a chest infection, to highlight the importance of clinical suspicion, careful examination, and appropriate imaging.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 30-year-old man with a history of asthma contacted an out-of-hours general practitioner with cough, green sputum, and shortness of breath. He was diagnosed with a chest infection and prescribed antibiotics. Over the following 48 hours, his symptoms worsened, with pleuritic chest pain and progressive breathlessness despite the use of inhaled bronchodilators.

EXAMINATION

On arrival, he was alert but tachypnoeic and complained of sharp central chest pain. His heart rate was 120 beats per minute, blood pressure was 132/87 mmHg, respiratory rate was 22 per minute, and O2 saturation was 96% on room air. Examination revealed a mild wheeze on auscultation, with palpable neck crepitus. The trachea was central, and there was no stridor.

INVESTIGATIONS

Blood tests were unremarkable (normal white cell count, C-reactive protein, and renal and liver profiles). ECG showed sinus tachycardia. Viral swabs, including SARS-CoV-2, were negative.

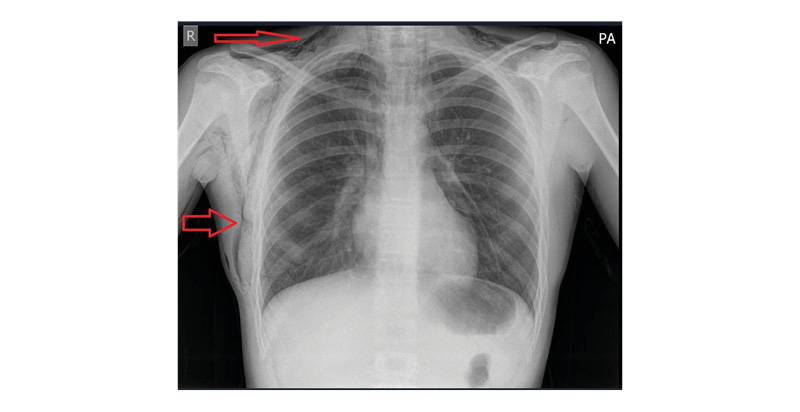

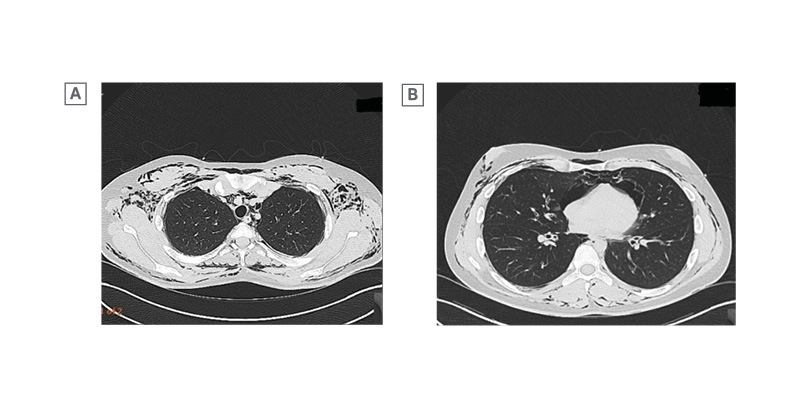

Chest X-ray demonstrated extensive pneumomediastinum with subcutaneous emphysema extending into the neck (Figure 1). CT thorax with contrast confirmed widespread mediastinal air, subcutaneous emphysema, and a small apical pneumothorax (Figure 2A and 2B). No oesophageal or tracheobronchial injury was evident.

Figure 1: Chest X-ray at presentation showing extensive pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema extending into the neck (arrows).

A) Axial view at the thoracic inlet, showing mediastinal air with extensive subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and chest wall. B) Axial view at mid-chest level, showing mediastinal air with subcutaneous emphysema. A small apical pneumothorax was present on more superior slices, not shown.

MANAGEMENT AND OUTCOMES

The patient was admitted under the cardiothoracic team and managed conservatively with high-flow O2, nebulised bronchodilators, and systemic corticosteroids. A chest tube was not inserted, as the pneumothorax was small, stable, and did not impair oxygenation.

He remained clinically stable and was discharged after 3 days. At the 2-week outpatient review, a repeat chest X-ray showed near-complete resolution of pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 3). His symptoms had fully resolved, with no recurrence.

Figure 3: Follow-up chest X-ray at 2 weeks demonstrating near-complete resolution of pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema.

DISCUSSION

SPM is an uncommon but recognised complication of asthma exacerbations. It occurs more frequently in young men and is associated with underlying lung disease, smoking, drug inhalation, or vigorous Valsalva manoeuvres.1,2,4,5 Recent reviews report asthma in about 20–25% of cases.2,6

The underlying mechanism of SPM is best explained by the Macklin effect, first described in 1944. A sudden rise in intra-alveolar pressure, typically triggered by coughing, forced expiration, vomiting, or an asthma flare, can cause alveolar rupture. The released air dissects along the perivascular interstitium towards the mediastinum and may extend into the neck and subcutaneous tissues. On CT, this appears as air tracking along the bronchovascular bundles, a classic but often under-recognised sign.3,7

Various other risk factors have been described in the literature, including recreational drug inhalation, blunt chest trauma, or infections such as H1N1 influenza. Cases linked to severe asthma exacerbation, as in the author’s patient, are well documented. A series by Panigrahi et al.8 highlighted the role of underlying lung disease in complicating the course of SPM. Published case reports (Elmoqaddem et al.9 and Lee et al.10) also demonstrate that early diagnosis, supportive management, and avoidance of unnecessary interventions result in favourable outcomes.

Clinical features most commonly include acute chest pain, dyspnoea, and subcutaneous emphysema. Careful examination is essential; in the author’s case, palpable neck crepitus was the key clue. Hamman’s sign, a crunching sound synchronous with the heartbeat, is described but uncommon.1

Chest radiography detects many cases, but CT is preferred because it detects small pneumothoraces or pneumopericardium and helps exclude secondary causes such as oesophageal rupture.7,11

Conservative treatment is usually sufficient. O2 can accelerate reabsorption of mediastinal air, and bronchodilators and corticosteroids are used to treat the underlying asthma.1,5,11 Antibiotics are not required unless there is clinical concern about infection or risk of mediastinitis.11

SPM is generally self-limiting with excellent outcomes. Most patients recover within days to weeks. Recurrence is uncommon but more likely in people with asthma or other chronic lung disease.6,12

This case reinforces the need to consider SPM in patients with asthma who present with atypical chest pain, particularly when standard therapy does not help, as early recognition avoids unnecessary investigations, antibiotics, or invasive procedures.

LEARNING POINTS

This case report highlights a few practical lessons for everyday clinical practice. Careful examination is still invaluable. In this patient, the finding of neck crepitus was the key clue that something more than asthma was going on. In young people with asthma who present with unusual chest pain, spontaneous pneumomediastinum should be kept in mind. Imaging is essential: a chest X-ray may suggest the diagnosis, but CT is more sensitive and will also show small pneumothoraces or exclude more serious problems. Most cases can be managed without invasive treatment, and even a small, stable pneumothorax can be safely observed. Recognising the condition early avoids unnecessary antibiotics or procedures and usually leads to a quick and complete recovery.

PATIENT PERSPECTIVE

“When I first became unwell, I thought it was just another asthma flare or a chest infection. The pain in my chest came on suddenly and was very worrying. I had never heard of this condition before and was frightened when the doctors told me that air had leaked into my chest and neck. They explained it clearly, which helped me to understand and feel reassured. I was relieved that I didn’t need any procedures, and with oxygen and my usual asthma treatment, I quickly felt better. I have made a full recovery, and I am thankful for the care I received.”

CONCLUSION

SPM is a rare but important differential in young adults with asthma presenting with acute chest pain. Prompt recognition, clinical examination, and imaging are essential for accurate diagnosis. Conservative management is usually sufficient, with an excellent prognosis.