Abstract

Within the heterogeneous group of diseases that constitute interstitial lung disease, biomarkers allowing for early disease identification could provide an opportunity for timely and tailored intervention to preserve lung function and quality of life. Tools for accurate forecasting of individual disease behavior, disease activity monitoring, prognosis, expected treatment response, and treatment safety risks from the point of diagnosis would be highly advantageous, yet remain largely elusive. Limitations in reliability, poor reproducibility, and prohibitive costs have been factors impacting the widespread implementation of most candidate biomarkers to date. This review evaluates the current and emerging biomarkers that may enable personalized assessment in patients with interstitial lung disease to augment clinical decision-making. Readily available clinical and physiological parameters are considered, along with emerging AI-assisted, high-resolution CT imaging, and molecular biomarkers found in blood, exhaled breath, and bronchoscopic sampling. The emerging data for multidimensional index or risk scores are also discussed.

Key Points

1. Interstitial lung diseases are often progressive and fatal, with no current therapies able to cure or reverse associated fibrotic processes. Biomarkers to improve diagnostic and prognostic precision, treatment response prediction, and new therapeutic target identification are critical.2. This is a narrative review synthesizing all relevant interstitial lung disease biomarker literature from 2003 onward, with a focus on existing and emerging biomarkers for refining approaches to clinically meaningful endpoints and management guidance.

3. The future of interstitial lung disease biomarker science lies in combining multiple biomarkers into robust, multidimensional risk indices that are likely to outperform single markers for more precise, individualized guidance for clinical decision-making.

INTRODUCTION

Clinically relevant and reliable biomarkers in interstitial lung disease (ILD) have been challenging to identify and validate, with very few translated into clinical practice to support therapeutic decision-making. A panel of robust biomarkers to enable delivery of personalized medicine in patients with ILD remains an important goal, particularly in the setting of early disease, where interventions could be most impactful. Compared with the field of oncology, precision medicine in ILD is still in its infancy. Yet within this complex and heterogeneous group of disorders, a model of individualized treatment strategies based on careful disease classification and behavior is evolving.

Biomarkers can be utilized for diagnosis, prognostication, monitoring, treatment responsiveness, drug safety assessment, and disease susceptibility in unaffected at-risk individuals.1 Those that are already available and applicable at minimal (or no) additional cost to healthcare systems are of greatest utility. For clinical translation, potential biomarkers need to be validated as reliable and reproducible, demonstrate cost-effectiveness, and substantially augment existing clinical options. Importantly, they need to be used in appropriate settings to minimize ambiguity in interpretation. Ideally, biomarker acquisition should pose minimal risk to the patient; however, some obtained through more invasive means may also prove valuable.

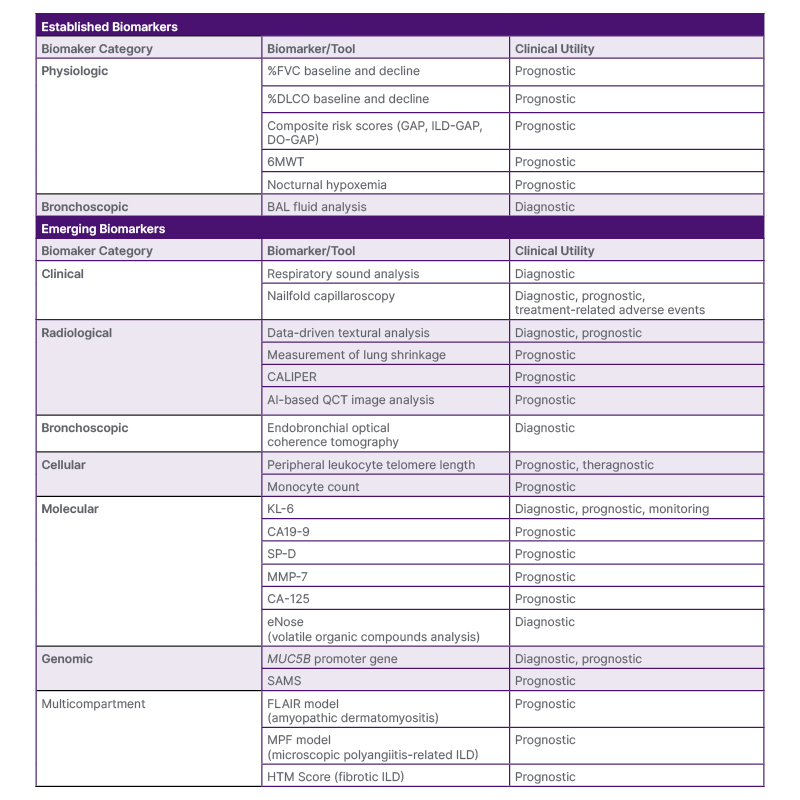

Disease-specific biomarkers needed for precision management in ILD remain largely in the research domain. Future alignment of clinical and preclinical biomarkers may further aid therapeutic development. Several well-established biomarkers are in current clinical practice, derived from high-resolution CT (HRCT) imaging, serology, physiologic testing, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid.2-7 Emerging techniques such as AI-supported HRCT analysis, eNose breath analysis, and peripheral blood leukocyte telomere length quantification are increasingly available in specialized centers, requiring further validation ahead of broader implementation (Table 1). This narrative review evaluates current and incipient biomarkers that could be feasibly incorporated into the personalized assessment of adult patients with ILD, based on evolving data.

Table 1: Summary of established and emerging biomarkers in interstitial lung disease.

6MWT: 6-minute walk test; %DLCO: percentage predicted diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide; %FVC: percentage predicted forced vital capacity; BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; CA 19-9: carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CA-125: cancer antigen 125; CALIPER: Computer-Aided Lung Informatics for Pathology Evaluation and Rating; DO-GAP: distance-oxygen-GAP index; GAP: Gender-Age-Physiology score; FLAIR model: serum ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase, antimelanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody (MDA5), HRCT imaging scores, and presence of rapid disease progression; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; HTM score: honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and peripheral blood monocyte count; ILD-GAP: interstitial lung disease GAP; KL-6: Krebs von den Lungen-6; MMP-7: matrix metalloproteinase 7; MPF model: %FVC, %DLCO, and presence of honeycombing on chest HRCT; QCT: quantitative computed tomography; SAMS: Scoring Algorithm for Molecular Sub-phenotypes; SP-D: surfactant protein D.

METHODS AND DEFINITIONS

A pragmatic narrative literature review was performed by the authors using PubMed to search MEDLINE for English language articles related to ILD biomarkers from January 2003–March 2025. Core search terms included “interstitial lung disease” OR “pulmonary fibrosis” AND “biomarkers,” with additional search terms selected as appropriate for the clinical question (e.g., AND “diagnosis”). Relevant publications involving adult patients were selected by the authors, with screening of publication bibliographies for additional evidence sources. Standardised definitions developed by the FDA and National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the 2016 Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools (BEST) framework are used within this review.1 The BEST framework distinguishes biomarkers (measured indicators of normal biological and pathogenic processes or responses to an exposure or intervention) from clinical outcome assessments (how someone feels, functions, or survives), noting the importance of both types of tools, often used simultaneously in clinical research.1

Clinical outcome assessments with demonstrated prognostic value include clinician-assessed prediction of survival, and several disease-specific symptom and functional status evaluation tools (e.g., the King’s Brief ILD [K-BILD] health status questionnaire).3 These clinician and patient-related outcome measures address important components of holistic care but are outside of the scope of this review.

VALIDATED PHYSIOLOGIC BIOMARKERS IN INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE

Several physiologic biomarkers are well established for severity assessment and monitoring of ILD, although they have limited diagnostic utility. Of multiple indices generated through comprehensive lung function testing, percentage predicted forced vital capacity (%FVC) and diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide (%DLCO) are the most robust for predicting outcomes.4 Lung function measures combined with other variables in composite risk prediction models have also been validated in various ILD populations.

Forced Vital Capacity, Diffusing Lung Capacity for Carbon Monoxide, and Composite Risk ScoresWhilst baseline FVC and DLCO consistently predict mortality and disease progression in ILD cohorts, longitudinal changes in these parameters appear to be better prognostic biomarkers. Even small relative declines in %FVC over 3–6 months have been linked with poorer survival,5 with one study reporting a minimally important difference of 3–6% decline over 24 weeks.6 A 12-month decline in FVC of ≥10% appears to be the most consistent predictor of increased mortality in fibrotic ILD subgroups, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), non-specific interstitial pneumonia, connective tissue disease-associated ILD (CTD-ILD), and fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP).4,7-10 Due to its relationship with disease progression and mortality, change in %FVC has been used as the primary endpoint in most IPF and progressive fibrosing ILD clinical trials.11-13

Decline in %DLCO is also predictive of increased mortality in ILD cohorts; however, measurement variability due to technical and disease-related factors has limited its reliability as a clinical trial endpoint.14 Lung function measurements also become less robust where there is mixed obstructive and restrictive physiology, as seen with the syndrome of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. In combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, spirometry and lung volumes appear relatively preserved and are not reliable disease severity indices.15 DLCO is disproportionately reduced with concomitant emphysema and/or pulmonary hypertension.

Additionally, an absolute FVC decline of 5–9%, a ≥10% absolute DLCO decline, radiological progression of fibrosis, or worsening symptoms as stand-alone or in combination criteria have also been shown to predict prognosis in non-IPF ILD cohorts.2

Several clinical risk prediction models have been developed to evaluate mortality risk, incorporating physiologic and demographic variables. The Gender-Age-Physiology (GAP) score (including baseline %FVC and %DLCO) was derived for mortality prediction in IPF but has been validated in other ILD subtypes (HP, CT-ILD, idiopathic non-specific interstitial pneumonia, and unclassifiable ILD) at different stages of disease (ILD-GAP).16,17

Various GAP model iterations have been studied to improve its predictive value.18,19 The distance-oxygen-GAP index (DO-GAP), incorporating 6-minute walk distance <250 m and exertional hypoxemia (peripheral oxygen saturation [SpO2] falling below 88%), was shown to outperform the traditional GAP model for all-cause mortality prediction (C-statistic: 0.756 versus 0.683; p=0.014).18

Exercise and Sleep Biomarkers

Lung physiology assessed in exercise and sleep can reveal key prognostic information. SpO2 <88% during baseline 6-minute walk test (6MWT) or cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) is strongly predictive of mortality in IPF and other ILD populations.20 The 6MWT also more closely correlates with health-related quality of life than FVC, noting that concomitant comorbidities such as pulmonary hypertension may impact test performance.21,22

Supine posture and reduced ventilatory drive during sleep also exacerbate oxygen desaturation relating to impaired respiratory function in patients with ILD.23 Nocturnal desaturation indices have been shown to predict mortality and the development of pulmonary hypertension in several studies utilizing polysomnography or overnight pulse oximetry. Nocturnal hypoxemia, measured as total sleep time with SpO2 <90% (total sleep time <90), was predictive of overall and progression-free survival in patients with ILD who were fibrotic.24 In a similar population, nocturnal hypoxemia was observed frequently in the absence of resting and exertional hypoxemia, with desaturation index (number of desaturation events >4% per hour overnight) found to be independently predictive of mortality.25

NOVEL CLINICAL BIOMARKERS

Detailed clinical assessment, including thorough history taking and examination, remains the cornerstone of ILD diagnosis. Through an iterative process, clinicians develop a probability for a specific diagnosis. The degree of confidence in the working diagnosis is modified by new data from supplementary testing. This Bayesian approach generates a likelihood or clinical “pre-test probability” for specific disease classification, an important determinant of performance characteristics of any subsequent diagnostic tests. Whilst many clinical examination findings are subjective and non-specific, some are quantifiable and appear to align with distinct diagnoses and clinical outcomes.

Respiratory Sound Analysis for Classification and Severity

Fine ‘velcro-like’ crackles auscultated with a traditional stethoscope are independently associated with the presence of the usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern characteristic of IPF, on HRCT, which in turn independently confers a worse prognosis.26,27 Digitally recorded velcro crackles similarly predict the extent of various fibrotic features on HRCT and the presence of UIP.28 This biomarker may be particularly valuable in early detection of ILD, and with assistance from digital recording stethoscopes, may feasibly improve remote patient assessment. Machine learning-based quantification of fine crackles has shown promise for ILD identification, severity scoring, and detection of image-based fibrotic features in a recent proof-of-concept study.29

Nailfold Capillaroscopy for Diagnosis, Prognostication, and Treatment-Related Adverse Events

Nailfold capillaroscopy (NFC) may be used as an adjunct to diagnose CTD-ILD where other established criteria for CTD diagnosis are not met.30 The non-invasive technique uses conventional microscopy or a smartphone dermatoscope to assess nailbed vascular patterns, where abnormalities are prevalent in scleroderma, dermatomyositis, and other CTDs.

While ILD-specific validation is limited, NFC has shown promise as a biomarker in scleroderma disease monitoring and prognostication.31 In 334 patients with scleroderma enrolled in the European Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) registry, baseline NFC patterns were associated with new or progressive organ dysfunction (including lung fibrosis).32 Associations were not established for individual organ systems, due to small subgroup numbers. A single-center study of 79 patients with scleroderma found NFC features were independently associated with lower baseline %DLCO and %FVC but did not predict longitudinal disease progression.33

Emerging Radiologic Biomarkers

The HRCT is recognized as highly reliable for evaluating suspected IPF in international guidelines.15 The discriminatory power of HRCT for identifying UIP has been convincingly demonstrated in studies using comparative histopathologic specimens. Where key features of UIP are all or mostly present, and pre-test probability of IPF is high, HRCT is sufficiently sensitive and specific to negate the need for lung biopsy.2 For patients with lower pre-test probability (e.g., female, non-smoker, younger age), HRCT reliability diminishes.34 Furthermore, HRCT analysis is affected by inter-observer variability. To address these limitations, more objective and reproducible imaging biomarkers for ILD screening, diagnosis, and prognosis have been developed. Automated HRCT scoring provides a quantitative measurement of fibrosis and can detect subtle disease progression.35 Different models with applied machine learning are summarized below.

AI for Radiologic Pattern Recognition, Fibrosis Quantification, and Prognosis

The utilization of AI for ILD classification has been explored. Deep learning (DL), an AI subset, employs multi-layer neural networks for extraction of high-level image data.36 By training with different ILD cohort images, DL allows for automated detection and classification of various patterns and quantification of disease extent. Data-driven textural analysis (DTA) is a DL technique employing convolutional neural network algorithms to quantify the extent of fibrosis. DTA fibrosis extent assessment in patients with IPF predicts mortality and decline in pulmonary function tests.37 Measurement of lung shrinkage, a method that uses elastic registration combined with DL classifiers, has been shown to correlate with morphological and functional disease progression.38

Computer-aided lung informatics for pathology evaluation and rating (CALIPER; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA) is a widely used machine learning algorithm for texture analysis, demonstrating strong correlation with pulmonary function tests, survival, and lung function decline in fibrotic ILD.35,39 AI-based quantitative CT image analysis for lung volume quantification has been found to independently predict prognosis in patients with IPF.40

DL algorithms trained with radiologist UIP categorizations can help to classify and predict outcomes in fibrotic lung disease.41,42 AI detection of early disease, or interstitial lung abnormalities (ILA), has also been studied across several platforms. Using an ensemble of convolutional neural networks, researchers identified eight distinct ILA patterns preceding the development of ILD, with a reported sensitivity of 91.4% and specificity of 98.1%.43

For routine integration of AI-based HRCT imaging analysis into clinical practice, several limitations need to be addressed.44 Accuracy of AI-derived outcomes is largely dependent on the quality and quantity of input data. Furthermore, validation of results in large and diverse population cohorts is essential.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Biomarkers

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid analysis can be a valuable adjunctive diagnostic biomarker for certain ILD subtypes. It is particularly useful in diagnosing chronic eosinophilic pneumonia and pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, or for excluding differential diagnoses such as infection.45

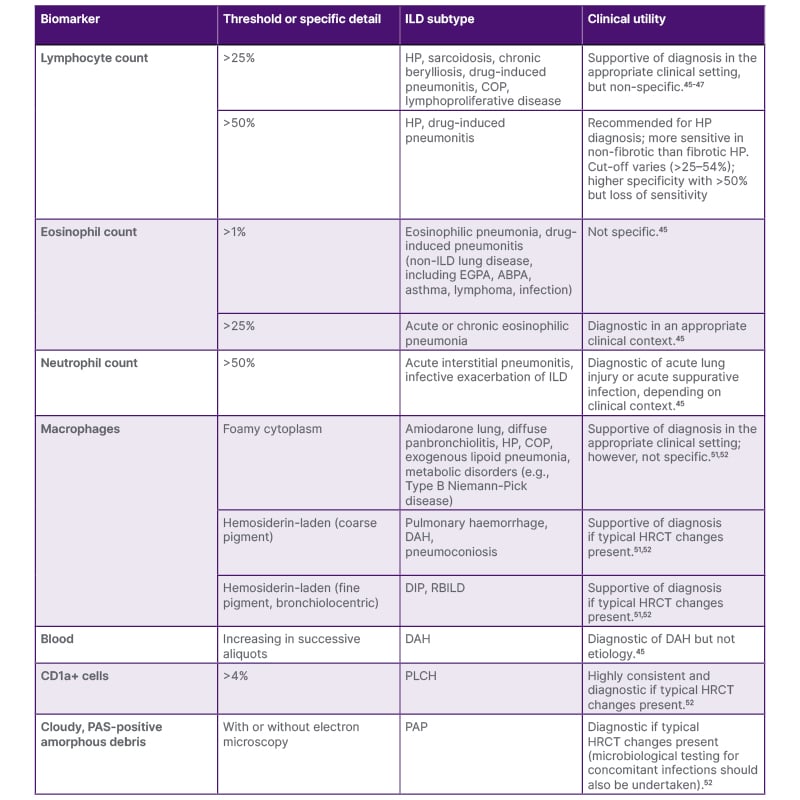

International guidelines recommend BAL fluid cellular analysis in the diagnostic work-up of suspected fibrotic and non-fibrotic HP.46 Various BAL fluid lymphocytosis thresholds have been reported in HP populations, with a pooled estimate of 43% (95% CI: 37–48%) in meta-analysis.47 Whilst this threshold could discriminate between IPF and chronic HP, HP and sarcoidosis were not distinguishable, with a mean lymphocyte count of 31% observed for sarcoidosis. Lower cutoffs resulted in lower specificity for HP, necessitating consideration of other causes of BAL lymphocytosis.47 Notably, elevated BAL lymphocyte counts are more likely to be present in non-fibrotic versus fibrotic HP, making this diagnostic biomarker less useful for the latter.47 Limited data suggest that high BAL neutrophil count may correlate with more severe disease,48 and worse prognosis,49 particularly during acute exacerbations of ILD.49,50 Diagnostic utility, however, is more limited to identifying lower respiratory tract infection, aspiration, or acute lung injury.45 Similarly, BAL macrophage profile may be supportive of various conditions relevant to ILD, but not of sufficient specificity to provide a definitive diagnosis.51,52 Specific BAL biomarkers are summarized in Table 2; however, validated BAL biomarkers for prognosis and treatment responsiveness are lacking.

Table 2: Diagnostic utility of bronchoalveolar fluid analysis in interstitial lung disease.

ABPA: allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; CD1a: cluster of differentiation 1a; COP: cryptogenic organizing pneumonia; DAH: diffuse alveolar hemorrhage; DIP: desquamative interstitial pneumonia; EGPA: eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; HP: hypersensitivity pneumonitis; ILD: interstitial lung disease; PAP: pulmonary alveolar proteinosis; PAS: periodic acid–Schiff staining; PLCH: pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis; RBILD: respiratory bronchiolitis–associated interstitial lung disease.

In Vivo, Real-Time, Near-Histologic Imaging

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a novel cross-sectional imaging technique showing promise as an adjunct to HRCT for diagnostic discrimination and utility for therapeutic and monitoring strategies, without the need for invasive tissue biopsy. OCT uses light interference to generate real-time 3D images with resolution <10 µm.53 Endobronchial OCT is performed by passing a narrow probe through a bronchoscope to the lung periphery and pulling back to identify near-histologic UIP features such as microscopic honeycombing, airway-centered fibrosis, and traction bronchiectasis. In one study, the technique demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity in differentiating UIP and non-UIP ILD.54 High agreement with traditional surgical lung biopsy for specific fibrotic ILD subtypes was also found. Polarisation applied to conventional OCT enables detection of collagen birefringence for in vivo fibrosis quantification. Increased birefringence was shown to correlate with greater fibrosis in comparative histologic samples, highlighting a potential non-invasive biomarker for future utility.55

CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR BIOMARKERS

Molecular biomarkers for ILD have been identified in serum, exhaled breath, tissue, and BAL. These biomarkers are usually non-invasively obtained, ideal for large-scale evaluation.

Single Protein Biomarkers

The epithelial glycoprotein Krebs von de Lungen-6 (KL-6) has been extensively studied as a candidate diagnostic, prognostic, and monitoring serum biomarker. Elevated KL-6 concentrations have shown high sensitivity and specificity for identifying patients with ILD compared to controls in several populations.56,57 KL-6 has also been associated with IPF mortality or progression, although findings have been inconsistent.57 Serial KL-6 measurement is used particularly in the Asia-region ILD clinics, with evidence for predicting disease progression, prognosis, and occurrence of acute IPF exacerbations.58 Considerable heterogeneity across studies and lack of a standardized cut-off or global assay method have limited the broader applicability of this biomarker.57

Other protein biomarkers, including matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP7), surfactant protein D (SP-D), and chemokine ligand 18 (CCL18), have been proposed, alone or in combination, to distinguish IPF from other ILD.58 With insufficient validation, they are not yet recommended for IPF diagnosis in international guidelines.

The landmark PROFILE study examined epithelial-derived serum biomarkers (CA19-9, CA-125, MMP7, SP-D), measured both at baseline and serially in treatment-naïve patients with IPF.59 Baseline SP-D and CA19-9 values were higher in patients with progressive phenotype versus those with stable disease. Increased MMP7 concentrations were associated with worse survival, and increased CA-125 concentrations over 3 months predicted mortality in patients with IPF. These results are confirmed in other cohorts where elevated SP-D, MMP7, and CA-125 were associated with increased mortality in both treatment-naïve and antifibrotic-treated patients with IPF and non-IPF ILD cohorts.60-62

Leukocyte Telomere Length

Peripheral blood leukocyte telomere length and telomere dysfunction markers are genetic biomarkers with increasing potential for guiding ILD treatment and prognostication. Post-hoc analysis of the PANTHER-IPF trial found that immunosuppressive therapy was associated with higher mortality and disease progression in those with telomere lengths <10th centile.63 Similarly, a retrospective study in patients with HP found worse outcomes in those with the shortest telomere lengths when treated with mycophenolate mofetil.64 Variable reliability and availability of platforms for measuring telomere length have limited widespread uptake of this testing to date.

Monocyte Count

Higher baseline blood monocyte counts (i.e., >0.6 K/μL) have been found to be predictive of disease progression, hospitalization, and mortality in several IPF cohorts.65 Levels, however, were not found to change over time with the introduction of antifibrotic therapy, limiting the utility of this inexpensive and widely available biomarker.

COMPOSITE MOLECULAR BIOMARKERS

Composite Protein Biomarkers

Composite protein biomarker signatures may more accurately reflect the heterogeneity of ILD subtypes and strengthen the individual protein performance characteristics. Accordingly, a composite three-biomarker index has been studied in patients with scleroderma to identify those at high risk of developing ILD.66 Another exploratory study in patients with fibrotic ILD found that a derived 12-biomarker proteomic signature from blood drawn at diagnosis could predict disease progression across different subtypes with a sensitivity of 90% in the validation cohort.67 Most of the proteins were of epithelial and mesenchymal cell origin.

eNose Technology

Breath-print assessment with electronic nose technology (eNose) involves non-invasive analysis of volatile organic compounds (VOC) in exhaled breath. VOC composition identified by eNose has been studied for identifying ILD versus healthy controls, and for phenotyping ILD subclasses.68 In a study of 322 patients with ILD, eNose could accurately identify distinct VOCs for IPF, interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF), and CTD-ILD with high sensitivity and specificity.69 This emerging composite molecular biomarker may have a role in rapid non-invasive diagnosis, particularly in early undifferentiated ILD.

GENOMIC BIOMARKERS AND POLYGENIC RISK SCORES

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS), chiefly performed in IPF and familial PF cohorts, have identified independent sequences associated with diagnosis, disease behavior, and survival.70 Polymorphisms in the MUC5B promoter gene have been found to be strongly associated with IPF, with >50% carrying the high-risk allele, rs35705950.71 More recently, this has been applied to at-risk populations and identified as an independent risk factor for ILD development in rheumatoid arthritis,72 and the presence and progression of ILAs are often described as ‘pre-clinical ILD’ in general populations.73 Using blood samples from IPF and ILA populations, polygenic risk scores (PRS) have been developed, both with and without inclusion of the MUC5B region due to its effect size.74 Whilst the PRS with MUC5B was more strongly predictive of IPF and ILA than the PRS without MUC5B, associations were strongest when clinical indices (age, sex, smoking history) were incorporated with either PRS. The PRS without MUC5B was also associated with ILA progression.

Separately, a 52-gene signature from peripheral blood was shown to be predictive of transplant-free survival in IPF.75 A PRS system ‘Scoring Algorithm for Molecular Sub-phenotypes’ (SAMS) incorporating this signature, was tested in multiple populations.76 The SAMS algorithm could discriminate patients with IPF into high and low-risk mortality groups after adjusting for clinical covariates. When combined with the GAP index, prognostic accuracy significantly improved over GAP alone.75 Temporal change in SAMS scores was associated with FVC changes in some but not all cohorts, with the use of this tool in disease monitoring yet to be established.

MULTI-COMPARTMENT BIOMARKERS FOR ILD SUB-TYPE RISK PREDICTION

To date, novel biomarkers have fallen short of established physiologic measures for the prediction of ILD outcomes, and few have achieved general clinical application. Models incorporating multi-compartment biomarkers may be more useful for risk prediction for this heterogeneous disease group. For example, baseline monocyte count has been integrated into GAP models for IPF, showing modest improvements in predictive power.19

The FLAIR Model, combining serum ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), antimelanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody (MDA5), HRCT imaging scores, and presence of rapid disease progression, predicted 1-year mortality in amyopathic dermatomyositis-associated ILD.77 In 51 patients with MDA5 dermatomyositis, automated quantitative CT scoring combined with serum Ro-52 could predict the 6-month risk of developing severe ILD.78 Similarly, the MPF model portended respiratory mortality in microscopic polyangiitis-related ILD, combining physiological biomarker thresholds FVC <79.6%, DLCO <34.9%, and HRCT honeycombing.79 An easily-applied algorithm incorporating thresholds of HRCT fibrosis extent of 20% and FVC 70%, was strongly predictive of mortality in scleroderma-ILD.80

While many models are tailored to specific diseases, the HTM score, combining honeycombing and traction bronchiectasis scores with monocyte count (>0.65K/μL), was developed to assess risk of progression in fibrotic ILD of any subtype.81 In a retrospective, registry-based evaluation and validation study, the model showed sensitivity of 70.6% and specificity of 67.9% for HTM scores ≥2 in identifying patients at higher risk of progression and requiring antifibrotic treatment.81 Multi-compartment biomarker models may overcome the failings of single biomarkers; however, require further validation in larger prospective cohorts ahead of widespread implementation.

CONCLUSION

The field of ILD biomarker science has made important advances through the integration of well-established and widely available measures with novel and emerging technologies. AI-assisted imaging techniques and molecular risk signatures show promise for addressing limitations of previous candidate biomarkers. Future integration of multiple biomarkers into comprehensive multidimensional indices or risk scores is likely to enhance the effectiveness of individual biomarkers and better guide clinical decision-making, ultimately improving outcomes.