Interview Summary

Psoriatic disease is a chronic condition that affects both physical and psychological health. Some patients experience stigmatisation, as well as social and professional limitations. The detrimental impacts of the condition can be summarised under the overall umbrella of wellbeing, with evidence accumulating that psoriasis impacts the wellbeing of both patients and their families. Patients with psoriasis have traditionally been evaluated using the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI), which assesses disease severity, and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), which examines quality of life. Both of these measures fail to adequately evaluate wellbeing.In these interviews with EMJ, Matthias Augustin, Director of the Institute for Health Services Research in Dermatology and Nursing (IVDP), University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany; and Ulrich Mrowietz, Psoriasis Center, Department of Dermatology, University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel, Germany describe the landmark POSITIVE study, the relevance of looking beyond skin lesions and including measures of wellbeing in clinical practice, and how the 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5) can be used to assess wellbeing in patients with psoriasis. They discuss POSITIVE, the first clinical study in dermatology to use patient-reported wellbeing, assessed using the WHO-5, as a primary endpoint to estimate the impact of the IL-23p19 inhibitor, tildrakizumab, on overall wellbeing in a real-world setting. The POSITIVE study is a new landmark for psoriasis management, and demonstrated that treatment with tildrakizumab was associated with improvements in disease severity, and increased wellbeing of patients, recovering back to normal population levels. This is the first time that a biologic treatment for psoriasis has shown these results. The interviewees concluded that wellbeing assessments should be incorporated into daily clinical practice to evaluate treatment response, and provide patients with more holistic management.

INTRODUCTION

Psoriatic disease is a chronic, inflammatory immune condition affecting more than 40 million individuals worldwide.1 In addition to the physical disability associated with the disease, there is increasing evidence demonstrating that it impacts the wellbeing of patients and their families.2-4 New data show how evaluation of patient and family wellbeing could be improved, providing dermatologists with a tool to more comprehensively assess the impact of treatment.5

THE EFFECTS OF PSORIASIS ON WELLBEING

Matthias Augustin

Augustin described the effects of psoriasis on wellbeing, current methods of assessment, how measurement might be improved, and the impact this could have on daily clinical practice.

What Does the Literature Tell Us About How Psoriasis Affects the Wellbeing of Patients and Families?

Psoriasis has a negative impact on the lives of patients, their families, and other people in their social environment.2-4,6 For patients, psoriasis impacts physical appearance, and causes itching and pain.7 However, the effects of the condition are far-reaching, with eight in 10 patients experiencing stigmatisation, as well as social and professional limitations.8 These detrimental impacts can be summarised under the umbrella of wellbeing,6,9 which is a construct that encompasses all areas of life that may be impaired due to the skin disease.

What Do Patients Tell You About Their Wellbeing?

It is multifaceted, and it takes time to understand the full picture of the burden of disease, particularly since some patients do not communicate their problems, and withdraw from life. I have seen many patients who have not received effective treatment, and who have stopped social contact with others. They do not go to the theatre or the swimming pool, and they do not participate in sports because they do not want to experience others staring at them. Some weeks ago, I saw a patient who had been banned from a public sauna because of his skin condition, even though he emphasised that it was not contagious, and therefore no risk to others. This negative treatment happens throughout life, including bullying in children, and stigmatisation at work. I had a patient working in a bank who told me that customers did not want to take money from him because they thought the lesions on his hands were contagious.

Most patients who come to me have lived with their disease for decades. They start with the hope, mostly in adolescence, that they will be cured. Over time there is disillusionment, and sometimes fear that the condition may continue throughout their life. Thus, the long-term course of the disease, and the omnipresence of the feeling on the skin, contributes to their loss of wellbeing.

Is the Psychological and Social Impact of the Condition Generally Underestimated by Healthcare Professionals?

Yes, for some it is surely underestimated, and many do not take the time to ask about this.9 When the skin shows lesions and is inflamed, the reflex of a dermatologist is to address the lesions. Of course, this is one of the tasks, but it is very mechanistic, and there is a lot under the surface that may be even more relevant than the visible skin lesions. It is this aspect that many dermatologists fail to explore on an individual patient level. For patients, this is another negative pressure if they are not permitted to talk about what is burdensome to them. They need relief from the emotional pressure.

What Are the Standard Methods of Psoriasis Assessment in Clinical Practice? Do They Adequately Evaluate Wellbeing?

In clinical practice, psoriasis is typically assessed using the PASI, the Physician Global Assessment (PGA), and the DLQI.10 The PASI and PGA evaluate disease severity, while the DLQI has been used to measure symptoms and their impact on quality of life.6,10

It is clear that we need to measure both the objective phenotype of the disease and the subjective perception of the patient, because one doesn’t replace the other, and they don’t even correlate closely.11 The PASI, for example, has been used for decades as an objective assessment of clinical severity.12 It is also used in most clinical trials, and has become a reference method.12 As for subjective burden, the DLQI is a pragmatic and validated tool,13 and has been widely used in research. However, the DLQI has several shortcomings. One is that it only provides a snapshot of 10 items relating to quality of life,14 without capturing the full spectrum of patient-relevant considerations. Second, the DLQI combines different elements into one question (for example, problems with a partner, close friends, and relatives), making it difficult to interpret the answer.14 Third, the structure of the instrument will lead some patients to respond that a particular question is “not relevant” to them.15,16 For example, there are questions about the impact of the skin condition on sexual life and on work. Patients who do not work or do not have a partner because of their disease typically answer “not relevant,” and receive a score of 0. The DLQI, therefore, underestimates disease severity, and the extent of quality of life lost.15,16 The result is that we need an additional assessment that captures wellbeing.

Why Is the World Health Organization’s Statement on Wellbeing, “Health Is a State of Complete Physical, Mental, and Social Wellbeing and Not Merely the Absence of Disease or Infirmity,” Important for Patients with Psoriasis?

The ambition [of this statement]17 is to normalise patient’s lives, and not just alleviate their symptoms. For patients with psoriasis, one target of treatment is to eliminate the skin lesions. However, we also need to address the psychosocial burden of the disease, including the cumulative life course impairment, which comes from missing things in life. Some people have an accumulation of burden which may seem irreversible, even if the lesions are clear.

What Is the Added Value of the 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index Questionnaire for Assessing Wellbeing?

The WHO-518,19 has three main advantages over the DLQI and other assessment tools. One is the positive wording of the items, which focus on achieving goals, rather than on reducing burden. For example, feeling cheerful, calm and relaxed, active and vigorous, and fresh and rested, as well as having a life filled with interesting things. When I started using the WHO-5, some patients smiled and laughed at the questions, which they found more inspiring than typical assessments about burden.

A second advantage is that the WHO-5 is a generic instrument that applies to all individuals, and all diseases. It, therefore, evaluates wellbeing in the context of comorbidities, which is important for holistic treatment. This is particularly relevant in psoriasis, which is associated with increased risks of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, mood disorders, obesity, and many other conditions.20

Thirdly, the WHO-5 is very sensitive, and superior to DLQI, in detecting early signals of deterioration due to disease.21 This provides an indication to start treatment, improve treatment, or even change treatment.

Why Is Wellbeing Becoming a New Endpoint in Clinical Studies?

Wellbeing is the ultimate goal of treatment for all patients.6 This is the most succinct way of stating what we want to achieve. Of course, there are diseases that are life-threatening, and we want to save lives, but even then, it is not just about saving lives. It needs to be associated with a liveable life. In patients with chronic inflammatory skin diseases, wellbeing is undoubtedly the key goal,6 as well as an assessment aim of the World Health Organization (WHO)17 and national health programmes.10 We, therefore, need further clinical studies to investigate whether new therapies are successful in achieving this aim.

How Might Wellbeing Assessment be Incorporated into Daily Clinical Practice?

The WHO-5 questionnaire is not difficult to adopt; it is a short and intuitive questionnaire, and patients understand how to complete it. However, any outcomes tool needs to have an impact on decision-making. I see the impact of the WHO-5 first of all in its use as a screening tool for psychosocial burden. The WHO-5 total score ranges from 0–100, where 0=absence of wellbeing and 100=maximal wellbeing, with a difference of 10 points being considered the threshold for a clinically relevant change.18 A cut-off of ≤50 is used when screening for depressive symptoms, with ≤28 suggesting moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms.18 In our clinical practice, if a patient has a WHO-5 score of <40, then we know that we need to do something more than just prescribe a drug against psoriasis. The patient may benefit from psychological therapy, for example. It may even be that the losses of wellbeing are independent of the skin condition, and are instead due to other severe diseases or financial difficulties, but this also impacts the skin disease, and so we need to know.

A second use for the questionnaire is that when we see no gain in wellbeing according to the WHO-5, then at some point we need to change treatment. In my clinical practice, we have set this point at 4 months. If there is no improvement in wellbeing after 4 months of taking a particular medication, then we discuss treatment change. Thus, information on wellbeing is more than just a ‘nice to have’; it should also have a real impact on decisions about treatment and management.

ASSESSMENT OF WELLBEING IN THE POSITIVE STUDY

Ulrich Mrowietz

Mrowietz discussed the first clinical study in dermatology to use patient-reported wellbeing (as assessed by the WHO-5) as a primary endpoint to estimate the impact of the IL-23p19 inhibitor, tildrakizumab, in a real-world setting. POSITIVE is an ongoing 24-month, Phase IV observational multinational study in adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis treated with tildrakizumab.6

What Was Innovative About the POSITIVE Study?

There are several aspects of the POSITIVE study that are innovative. Indeed, we tend to call this a groundbreaking study because we have implemented a completely different way of assessing the benefit of a treatment for patients. In virtually all studies that have been performed so far, measures of psoriasis disease severity, such as the PASI and PGA, have been used as a primary endpoint. In some cases, these measures were used together with a non-psoriasis-specific patient-reported outcome, such as the DLQI, as a co-primary endpoint. The aim of this type of study is to assess the efficacy and safety of a given drug in a patient population. However, we think that this does not adequately capture the patient’s perspective.

Our assessment in the POSITIVE study reflects an initiative introduced in 2007 by the WHO, called ‘people-centred healthcare’.22 This initiative states that “the essence of people-centred health care and health systems involves a balanced consideration of the values, needs, expectations, preferences, capacities, and health and wellbeing of all the constituents and stakeholders, and encompasses the ill and those who are well. Transforming the current health care system towards a people-centred orientation requires comprehensive and positive changes spanning four key policy and action domains: individuals, families, and communities; health practitioners; health care organisations; and health systems.”23

A key element of this initiative is that we should no longer ask patients, “What is the matter with you?”, but should ask, “What matters to you?” I always mention this when I give presentations about rethinking psoriatic disease, because this puts the patient at the centre again. The WHO-5 questionnaire was introduced to assess the overarching principle of wellbeing.19 In general medicine, the WHO-5 questionnaire has primarily been used in psychiatry and in diabetology.18 In our research, we have previously shown that the WHO-5 is more effective than the DLQI at assessing wellbeing in patients with psoriasis.21 So, the most important novel aspect of POSITIVE is that it was the first clinical study in dermatology to use patient-reported wellbeing as the primary endpoint in the context of a global, people-centred healthcare approach.6

A second innovative aspect of POSITIVE was that we wanted to encompass the entire environment of the patient. That includes partners and family, as well as treating physicians. In the study, we used the FamilyPso questionnaire to assess the burden that the disease of a partner brings to family members.24 The questionnaire has 15 items divided into five domains: perceived strain by social reactions to the partner’s psoriasis; strain caused by cleaning; acute emotional strain attributed directly to the psoriasis; restrictions of social life; and general emotional strain. The items are scaled in a five-point Likert format: 0=not true; 1=somewhat true; 2=moderately true; 3=quite true; and 4=very true, with the supplementary option of “does not apply to me.” The Physician’s Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ), which was created for this study based on the compassion subscale of the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) questionnaire, was used to evaluate the long-term benefit of tildrakizumab on physician satisfaction with treatment.6,25

What Are the Latest Findings of the POSITIVE Study?

An interim 28-week analysis of the POSITIVE study was presented for the first time at the 32nd European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) conference in October 2023 in Berlin, Germany.5 The objective of this study is to assess the effectiveness of tildrakizumab on the overall wellbeing of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated with tildrakizumab in routine care. A total of 263 patients were enrolled in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and the UK. The mean age was 46.3 years, 65.8% were male, the mean BMI was 28.2 kg/m2, and 34.2% were current smokers. At baseline, the mean WHO-5 score was 53.9. To put this into context, the mean WHO-5 score was 63.9 in the general population of the countries participating in the POSITIVE study, 52.2 among females with breast cancer, and 56.0 in patients with Type 2 diabetes.

The mean WHO-5 score significantly increased from 53.9 at baseline to 67.1 at Week 16 (p<0.001; mean change from baseline of 12.4), and to 67.3 at Week 28 (p<0.001; mean change from baseline of 12.7).5 At baseline, 41.2% of patients had a WHO-5 score ≤50 (17.6% of patients ≤28), decreasing to 20.2% (5.2% of patients ≤28) and 20.6% (5.7% of patients ≤28) at Week 16 and Week 28, respectively. After just 16 weeks of treatment with tildrakizumab, wellbeing scores had significantly increased compared with baseline, and were similar to the general population. This benefit was maintained up to Week 28.

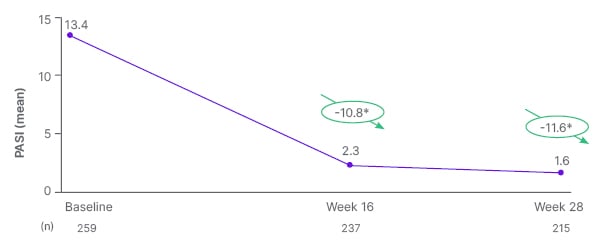

The improvement in wellbeing occurred in parallel with improvements in disease severity. Mean PASI score decreased from 13.4 at baseline to 1.6 after 28 weeks of treatment with tildrakizumab (p<0.001), a mean change from baseline of −11.6 (Figure 1).26 At Week 28, 92.6%, 85.1%, and 55.3% of patients achieved PASI ≤5, PASI ≤3, and PASI ≤1 responses, respectively. Taken together, we see the benefit of tildrakizumab to patients not only through the WHO-5 score, but also through the somatic PASI score, which indicates that a high proportion of patients are virtually clear of skin lesions after 28 weeks of treatment. Furthermore, no new safety signals were observed, and 28-week interim safety data, also presented at the EADV conference,27 was consistent with previous studies.28,29

Figure 1: Absolute PASI score up to week 28.26

*Mean change from baseline (p<0.001). PASI range: 0–72, no disease to maximal disease.

PASI: Psoriasis Area Severity Index.

At the conference, 28-week interim data on the impact of psoriasis on the wellbeing of partners of patients included in the POSITIVE study were also presented.30 The wellbeing of partners was assessed using the FamilyPso questionnaire. Of 263 patients included in the study, 162 (61.6%) had a partner. The questionnaire was completed by 113 partners at baseline, and 64 partners after 28 weeks of patient treatment with tildrakizumab. The mean total FamilyPso score decreased from 1.3 at baseline to 0.8 at week 28 (p<0.001), with a mean change from baseline of −0.4. The mean FamilyPso scores for each domain at baseline and Week 28, respectively, were 1.1 and 0.7 for “perceived strain by social reactions to the partner’s psoriasis,” 1.4 and 1.0 for “strain caused by cleaning,” 1.2 and 0.7 for “acute emotional strain attributed directly to the psoriasis,” 0.9 and 0.4 for “restrictions of social life,” and 1.9 and 1.3 for “general emotional strain.”

Why Are the Findings of the POSITIVE Study Important?

The POSITIVE study is a new landmark for wellbeing in psoriasis. The study demonstrated that treatment with tildrakizumab was associated not only with improvements in disease severity, but also with improvements in the wellbeing of both patients and their partners. This is the first time that a biologic treatment for psoriasis has shown these results.

What Would You Like to See Happen in Future as a Result of the POSITIVE Study?

We think that it is more appropriate to use a patient-centric endpoint, such as the WHO-5, as well as the term wellbeing, instead of simply measuring PASI, PGA, and DLQI. Otherwise, we miss what the disease, and the treatment of the disease, really mean to patients and families.

There is a need to spread the knowledge that psoriasis can be managed by assessing lesion severity (for example, with PGA or PASI), as well as assessing wellbeing with the WHO-5. After a period of treatment, the assessments should be repeated to see if there is improvement. Our ultimate goal is for patients and their partners to be happy. In the scenario of shared decision-making, where patients are informed about the disease and potential treatments, we could also include input from the partner of the patient. The investigators of the POSITIVE study hope to communicate our ambitions for wellbeing assessment on a global scale, by embedding the concept into a renewed WHO global report on psoriasis.31

CONCLUSION

Psoriasis has wide-ranging physical and psychological effects on patients and their families. Current assessment methods fail to adequately evaluate the full impact of the disease. The WHO-5 questionnaire is a practical measure for examining patient wellbeing in clinical trials, and in clinical practice. The POSITIVE study demonstrated that tildrakizumab, was associated with improvements in disease severity, and with increased wellbeing in patients and their partners. Incorporating wellbeing assessment into daily clinical practice would lead to more holistic management of patients with psoriasis.