Abstract

Background: Severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCAR) can be traumatic and emotionally distressing for both the patients and their families. However, caregivers must also take care of themselves to prevent burnout. They should seek respite when needed, and prioritise self-care activities that maintain their own wellbeing.

Aim: This study aimed to explore the caregiver’s burden and resilience in patients experiencing SCARs.

Methods: A cross-sectional observational study included patients experiencing SCARs who presented with their caregivers. Patients and their caregivers were enquired about their sociodemographic variables, and were administered the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS). Caregivers were further given the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (BSFC) and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQOL-BREF).

Results: Quality of life assessment suggested diminished physical and psychological health among the caregivers. Burden grade conferred 27.1% of caregivers experiencing severe burden, while 56.5% and 16.5% of caregivers experienced mild and moderate burden, respectively. Furthermore, 85.9% of caregivers showed low resilience. Increase in reaction severity was associated with greater caregiver burden and low resilience (p=0.001). Higher age and lower socioeconomic strata were also associated with increased burden and lesser caregiver resilience (p<0.001).

Conclusion: Providing care for individuals with SCARs can be physically and emotionally demanding, requiring assistance with daily activities, wound care, and medication management. Caregivers may face challenges as they navigate the complexities of the condition; hence, understanding and addressing the challenges faced by caregivers is of utmost importance.

Key Points

1. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCAR) can be traumatic and emotionally distressing for both patients and their families. Alongside the delivery of support and care, it is important that caregivers also look after themselves to prevent burnout.2. This study explored the caregiver burden and resilience in 85 patients experiencing SCARs using relevant questionnaires. The findings showed that 27.1% of caregivers experience severe burden.

3. Besides prioritising patient outcomes, disease management, and treatment efficacy, a compassionate understanding of caregiver burnout and informed communication can help in the holistic management of patients with SCAR.

INTRODUCTION

Severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions (SCAR) are a group of rare but potentially life-threatening conditions that can occur in response to certain medications. These reactions include conditions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and drug reactions with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Resilience, in the context of SCARs, refers to a patient’s ability to cope with and recover from these severe reactions, both physically and emotionally. Knowledge about SCARs, their causes, treatment options, and potential outcomes can empower patients and their families to actively participate in their recovery process.1 Understanding the condition can alleviate fear and anxiety. Adhering to medical treatments, such as wound care, medications, and follow-up appointments, is crucial for recovery. It is important to note that every individual’s experience with SCARs, and their recovery journey, will be unique. Healthcare providers, mental health professionals, and support groups can all play crucial roles in helping patients build resilience, and navigate the challenges posed by SCARs.2 Caregivers play a pivotal role in supporting these patients. These reactions can be physically and emotionally demanding for patients, often requiring significant medical attention and support. Caregivers provide essential assistance, comfort, and advocacy throughout the patient’s recovery process.3

SCARs can be traumatic and emotionally distressing for both patients and their families.4 Caregivers offer emotional support by providing a listening ear, offering words of encouragement, and being empathetic to the patient’s feelings and concerns. They ensure that the patient’s medical needs are met. SCARs can significantly limit a patient’s ability to perform basic activities like bathing, dressing, eating, and mobility.4 Caregivers may provide physical assistance with these tasks, helping the patient maintain their dignity and comfort. They help manage the patient’s medication regimen, ensuring that medications are taken as prescribed, tracking dosages and schedules, and noting any adverse effects or improvements. In severe cases, these reactions can cause extensive skin damage and open wounds. Caregivers may be responsible for assisting with wound care, including cleaning, dressing changes, and following medical instructions for proper care.5 They further ensure that the patient maintains proper nutrition and hydration, as these factors play a crucial role in the healing process. They might prepare meals, provide water, and monitor the patient’s intake; and may be responsible for transporting the patient to medical appointments, follow-up visits, and therapy sessions as needed, helping ensure that the patient receives timely medical care and support.

Caregivers often serve as a bridge of communication between the patient and healthcare providers. They help relay important information, questions, and concerns to the medical team and vice versa. Caregivers also help create a positive and supportive environment that contributes to the patient’s emotional wellbeing. They engage in activities that bring comfort and joy to the patient, and they help manage any anxiety or emotional distress. Caregivers learn about the patient’s condition, treatment plan, and potential complications in order to provide informed care. This education helps them make informed decisions, and offer explanations to the patient and family. However, caregivers must also take care of themselves to prevent burnout.6 They should seek respite when needed, and prioritise self-care activities that maintain their own wellbeing.

The prevalence of SCARs varies widely depending on the specific type of reaction and the population studied. The annual incidence of SJS and TEN7 combined is estimated to be between one and six cases per million people worldwide, and DRESS syndrome is estimated to occur in one in 1,000 to one in 10,000 drug exposures.8 Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis, considered a rare occurrence, has an estimated incidence of one to five cases per million people per year.9 However, these incidences can be higher in certain populations with specific drug exposures. Healthcare research often prioritises patient outcomes, disease management, and treatment efficacy. While these are crucial, there is a growing recognition of the importance of understanding and addressing the challenges faced by caregivers. Despite having a significant prevalence with a known impact of SCARs on the physical and emotional wellbeing of the patient, research on the aspects of caregiver burden has not been explored. The present study thus tried to address this dearth, and explore the caregiver burden and resilience in patients experiencing SCARs.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

The study had a cross-sectional observational design. It was carried out for a period of 2 years, in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Eastern India. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the School of Tropical Medicine, Kolkata, India (Approval No: CREC-STM/385). All the patients provided written informed consent after a full explanation of the protocol design, and the study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

The study included patients experiencing SCARs who presented with their caregivers on the first follow-up post-discharge, and who consented to be a part of the study. Consenting caregivers, as well as the patient, were required to provide written informed consent before participation. Patients with documented psychiatric comorbidities, or any other psychological conditions that could potentially impede their understanding of the questionnaire and accurate responses, were excluded from the study.

Variables and Data Measurement

Patients and their caregivers were enquired about their sociodemographic variables, and were given brief resilience scale (BRS) questionnaires.10 Caregivers were given assessment scales, namely the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (BSFC),11 and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQOL-BREF).12

The BRS10 is a self-report assessment tool used to measure an individual’s ability to bounce back from stress and adversity. It is designed to assess resilience, which is the capacity to adapt and recover from challenging situations. The BRS is a short and simple questionnaire, often used in research and clinical settings to quickly evaluate an individual’s resilience level. It typically consists of six items, and respondents rate their agreement with each item on a scale, such as a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree). The questions on the BRS are meant to capture various aspects of resilience, including the ability to cope with stress, adapt to change, and maintain a positive outlook in the face of adversity. The scoring is obtained by adding the responses, and then dividing the total sum by the total number of questions answered. A score of 1.00–2.99 suggests low resilience, 3.00–4.30 suggests normal, and 4.30–5.00 suggests high resilience.

BSFC11 is a 28-item scale measuring subjective burden, with 4 points on scale, from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The BSFC helps assess the emotional, physical, and social burden experienced by family caregivers, providing insights into the challenges they face. This information can be valuable in healthcare settings for care planning, and in research studies to understand the impact of caregiving on family caregivers’ wellbeing. A cumulative score of 0–41 suggests no to mild burden, 42–55 suggests moderate burden, and 56–84 suggests severe-to-very-severe burden.11 Quality of life was adjudged using WHOQOL-BREF,12 a self-administered questionnaire comprising 26 questions on the individual’s perceptions of their health and wellbeing. The WHOQOL-BREF covers four domains, each with specific facets: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. There are also two separate questions which ask specifically about the individual’s overall perception of their health and quality of life.

Each of these generic instruments were pilot-tested in a representative population that was not included in the final study. Each instrument was used in the study population only if it yielded acceptable reliability measures. Caregivers were interviewed during their facility visit along with the patient for the scheduled (first) follow-up post-discharge.

Study Size

Considering the prevalence of cutaneous adverse drug reactions among hospitalised patients was 5% as reported,13 with a 5% allowable margin of error and a 95% confidence interval (CI), the estimated sample size of the study was 73. However, the study included a total of 85 patients, and analysed the data collected statistically.

Statistical Methods

Data collected were statistically analysed. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data, and the results were represented as mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentages, as applicable. p<0.05 was considered significant. The normality test using Shapiro–Wilk test showed that the measures were normally distributed; hence, a parametric approach was undertaken. Multiple linear logistic regression analyses were performed to find predictors for burden and resilience. The variables with variance inflation factor greater than 10 were omitted from the analysis to avoid multi-collinearity. All statistical tests were conducted on standard statistical software like SPSS Windows version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA).

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Characteristics

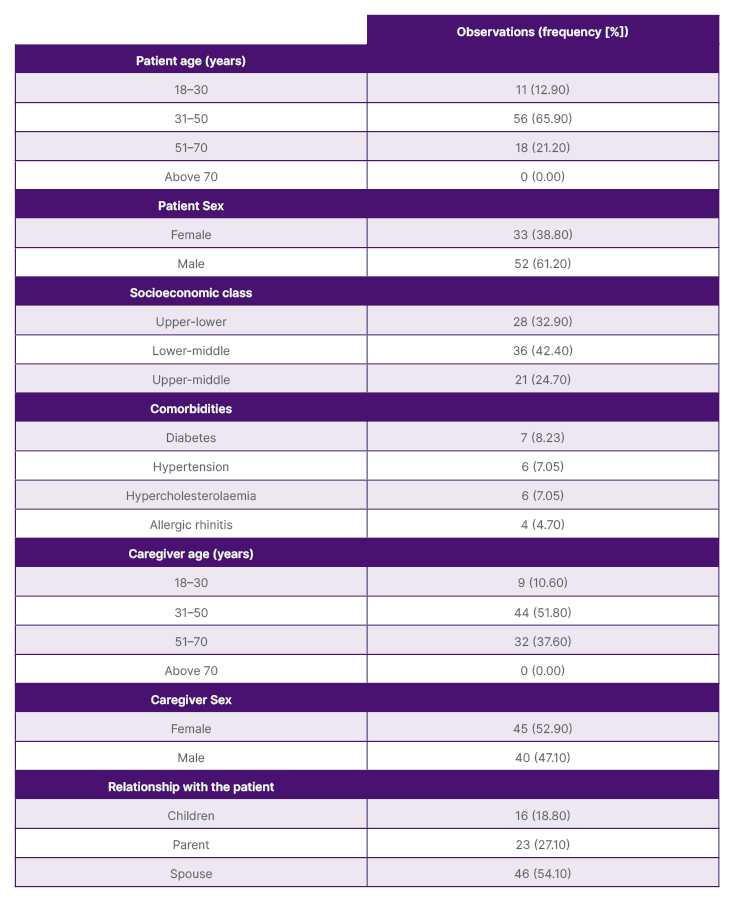

The study included a total of 85 patients with SCARs, whose caregivers were interviewed. Of the 85 patients, the majority were males (61.2%). The most represented age group was that of 31–50 years, followed by 51–70 years, and 18–30 years. The mean age of the patients was recorded as 41.85±8.90 (95% CI: 39.93–43.77). A total of 42.4% of patients belonged to the lower-middle class of socioeconomic strata, followed by 32.9% belonging to the upper-lower strata, and 24.7% belonging to the upper-middle socioeconomic class. Only 23 patients (27.05%) had comorbidities.

Among the 85 caregivers interviewed for this study, the majority belonged to the age group of 31–50 years, followed by 51–70 years. The mean caregiver age was 45.64±11.96 (95% CI: 43.06–48.22). A total of 52.9% of caregivers were females. Caregivers were mostly spouses (54.1%), followed by parents (27.1%) and children (18.8%; Table 1)

Table 1: Patient and caregiver characteristics.

Main Results

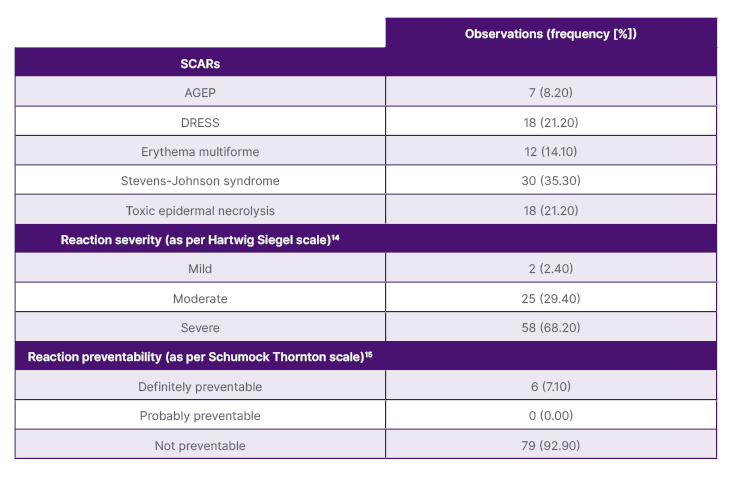

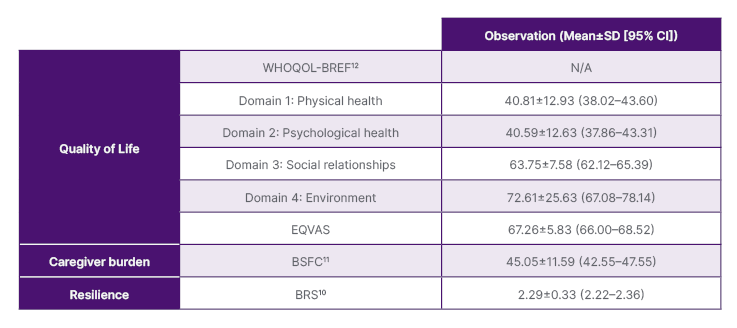

A total of 35.3% of patients experienced SJS, followed by 21.2% of patients experiencing DRESS and TEN. Erythema multiforme was experienced by 18 (21.25%) patients, and 8.20% of patients experienced acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis. No cases of SJS-TEN overlap were encountered. As per the Hartwig Siegel scale,14 68.2% of cases were assessed to be ‘severe’, followed by 29.4% moderate cases, and 2.4% mild cases. A total of 92.9% of SCARs were non-preventable as per Schumock Thornton Preventability Scale (Table 2).15 Post-SCAR sequelae were noted in two patients with TEN, and one patient with SJS. The noted sequelae in all three cases were ocular complaints, including eye pain and photophobia. Conjunctival hyperaemia was noted in one case of TEN. Quality of life was assessed using WHOQOL-BREF and EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQVAS). Mean domain scores of WHOQOL-BREF revealed diminished physical and psychological health among caregivers of patients with SCAR. Burden grade using the BSFC scale estimated that 27.1% (n=23) of the caregivers experienced severe burden, and 56.5% (n=48) and 16.5% (n=14) experienced mild and moderate burden, respectively. Using the BRS measure, 85.9% (n=73) showed low resilience, with the rest exhibiting normal resilience (Table 3).

Table 2: Characteristics of severe cutaneous adverse reactions.

AGEP: acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis; DRESS: drug reactions with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; SCAR: severe cutaneous adverse reaction.

Furthermore, the severity of the SCARs was correlated with the burden and resilience score. A significant association was observed with both measures, suggesting that the increase in reaction severity was associated with greater caregiver burden and low resilience among patients (p=0.001). Other factors, like age and socioeconomic class, were also probed for association. Higher age and lower socioeconomic strata were associated with increased caregiver burden and lesser resilience among patients (p<0.001). However, no significant association of caregiver burden was noted with the patient’s age (p=0.326) and comorbidities (p=0.214).

Table 3: Quality of life, burden, and resilience in severe cutaneous adverse reaction cases.

BRS: Brief Resilience Scale; BSFC: Burden Scale for Family Caregivers; EQVAS: EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale; N/A: not applicable; SCAR: severe cutaneous adverse reaction; WHOQOL-BREF: World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief.

Multivariable linear regression was conducted to examine the best combination of factors for predicting caregiver burden and resilience. Multivariate linear regression analysis showed that BRS score in SCAR cases was negatively affected by severity of adverse drug reaction (β: -5.588; standard error [SE]: 0.527; p=0.000; 95% CI: -6.623–-4.553) and patient’s age (β: -1.246; SE: 0.225; p=0.000; 95% CI: -1.688–-0.805). BSFC score was positively affected by the adverse drug reaction severity (β: 0.468; SE: 0.579; p=0.000; 95% CI: -0.669–1.605), and caregiver’s age (β: 0.178; SE: 0.207; p=0.000; 95% CI: -0.061–0.132). Age and reaction severity were the only strong predictors for both higher caregiver burden and lower resilience.

DISCUSSION

The impact of SCARs extends beyond the immediate medical consequences. Besides affecting mental health, quality of life, and economic wellbeing of the individual, it can also affect interpersonal relationships. SCARs can strain personal relationships as individuals cope with the physical and emotional aftermath of the condition. Family members and caregivers may also experience stress and emotional burden while providing support; therefore, a comprehensive and holistic approach to care, including medical, psychological, and social support, is essential for individuals affected by SCARs.16

The present study tried to assess the quality of life, burden, and resilience among caregivers of patients affected by SCARs. Quality of life assessment suggested diminished physical and psychological health among the caregivers. Burden grade conferred 27.1% of caregivers experiencing severe burden, while 56.5% and 16.5% of caregivers experienced mild and moderate burden, respectively, and 85.9% of patients showed low resilience. An increase in reaction severity was associated with greater caregiver burden and low resilience. Also, higher age and lower socioeconomic strata were associated with increased burden and lesser caregiver resilience.

Providing care for individuals with SCARs can be physically demanding, requiring assistance with daily activities, wound care, and medication management. The need for specialised care, including hospitalisation and frequent medical appointments, can disrupt caregivers’ daily routines and responsibilities. The economic burden of SCARs may also affect caregivers, especially if they need to take time off work, or incur additional expenses related to medical care and support.17 Balancing caregiving responsibilities with other family or work commitments can create tension and stress. Caregivers often take on the responsibility of learning about the condition, treatment options, and potential complications. They may need to advocate for the patient’s needs within the healthcare system, ensuring they receive appropriate and timely care.18

Supporting a patient through SCARs can be emotionally challenging, and caregivers may face challenges as they navigate the complexities of the condition. Caregivers need to have access to resources, support groups, and healthcare professionals who can offer guidance and assistance. Open communication, collaboration with the medical team, and a strong support network are all key components of a successful caregiving role in patients with SCARs.19 Caregiver burden can vary significantly depending on the specific disease or condition being cared for. A study by Cheng et al.20 examined caregiver burden and depression in dementia caregivers. Neuropsychiatric symptoms were found to be most predictive of caregiver burden and depression, regardless of the specific dementia diagnosis. Disruptive behaviours (such as agitation, aggression, and disinhibition) had a significant impact on caregivers’ emotional wellbeing. These symptoms strain the emotional connection between caregivers and care recipients. A study by Mwinbam et al.21 highlighted family caregivers’ experience and barriers in caregiving children with cerebral palsy, in a resource-limited context, in Northern Ghana. Caregiving in the context of chronic diseases has also been researched. Luttik et al.22 explored the determinants of caregivers’ burden in cases of patients with heart failure. They commented that the burden assessment should focus on the mental strength of the partners, and highlighted the challenges caregivers face in managing complex medication regimens, symptom monitoring, and lifestyle modifications. According to a study by Onyeneho et al.23 on family carers for patients with cancer, providing care has an impact on the patients’ social, physical, psychological, and financial spheres of life. The majority of carers, the study found, were only somewhat burdened. This is easily explained by the fact that, despite the burden being there, most people are reluctant to voice their opinions due to their relationship with the care recipient. The authors’ results support this opinion.

The concept of a caregiver support system is evolving, with a growing recognition of the importance of supporting caregivers, to ensure the wellbeing of both the care recipients and the caregivers themselves.24, 25 Primarily, family plays a significant role in caregiving in culture. In many cases, family members, especially spouses, children, or extended family, take on the responsibility of caregiving. This support can include emotional, physical, and financial assistance. Apart from this, community support networks, such as religious or community groups, can provide valuable assistance to caregivers, and may offer respite care, support groups, educational resources, and counselling services.26 Several non-governmental organisations in India focus on providing support and services to caregivers. These organisations often offer training programmes, counselling, support groups, and advocacy efforts to raise awareness about caregiver needs and challenges. The Indian government has various schemes and programmes aimed at supporting caregivers, especially for elderly care and persons with disabilities.

These initiatives may include financial assistance, caregiver training, and access to healthcare services. Hospitals, clinics, and healthcare providers also offer caregivers’ education, counselling services, and respite care options to alleviate caregiver burden. With the advancement of technology, digital platforms, mobile applications, and telehealth services are increasingly being used to provide support and resources to caregivers. These platforms offer information, communication tools, and virtual support groups.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study highlighting the caregiver’s health when handling patients with SCARs. This study definitely has its own limitation of being a single-centre, small sample study, but it undoubtedly paves the path for caregiver-related research works in this domain. Due to the cross-sectional design of this study, the authors were unable to evaluate the longitudinal effects on caregiver burden and resilience. Therefore, a longitudinal impact assessment is necessary to address this gap in understanding.

CONCLUSION

SCARs have a physical, mental, and social toil on the patient as well their caregivers. Besides prioritising patient outcomes, disease management, and treatment efficacy, a compassionate understanding of caregiver burnout, and informed communications can help in the holistic management of the patient with better patient outcomes.