Abstract

Dermatitis artefacta (DA) is a rare psychocutaneous disorder characterised by self-inflicted skin lesions that the patient denies producing. DA poses a complex clinical challenge to clinicians as patients often are resistant to the diagnosis, and can be hesitant to follow up with psychiatric or psychological services. There is a need to understand the optimal approach for management of patients with DA. This systematic review was undertaken to address this gap in knowledge.

A search was conducted on PubMed and Embase using the following search strategy: Dermatitis artefacta OR factitious dermatitis OR factitial dermatitis OR artefactual skin AND treatment OR management OR therapy OR psychotherapy OR pharmacotherapy. Included studies were published from inception to 5ᵗʰ April 2023 in peer-reviewed journals, and discussed the treatment and management of DA. Studies were excluded if they were published in a language other than English.

A total of 11 retrospective or prospective studies were included in this systematic review. They all found DA to be challenging to treat, with every study reporting patients experiencing a comorbid psychiatric condition or associated psychosocial stressor. Overall, there were better reported outcomes among follow-up patients treated in psychodermatology clinics with multidisciplinary teams of dermatologists, psychiatrists, and psychologists.

Medical treatments can help with symptom control and promote wound healing, while psychological and psychiatric treatments can help address underlying psychosocial stressors for the condition. Further research is needed to evaluate optimal management and long-term treatment outcomes in patients with DA.

Key Points

1. Dermatitis artefacta is a complex psychocutaneous condition that poses a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for clinicians. The lesions are bizarre, angular, or geometrical, not conforming to any recognised skin disease.2. In this systematic review, 11 studies were reviewed with the aim of evaluating the treatment of dermatitis artefacta.

3. Clinicians should consider a multidisciplinary approach with a team of dermatologists and mental health professionals in the treatment of dermatitis artefacta.

INTRODUCTION

Dermatitis artefacta (DA), also known as artefactual skin disease, is a rare psychocutaneous disorder characterised by self-inflicted skin lesions that the patient denies producing. DA is considered a primary psychiatric disorder with a dermatological presentation, as patients create lesions on the skin to satisfy an underlying psychological need.1,2 DA occurs more commonly in females, and is mainly seen in older children and adolescents, although all age groups may be affected.2,3

The lesions of DA can mimic recognised skin conditions; however, in most cases, the morphology and distribution of these lesions do not align with conventional dermatological patterns. DA is typically identified by its irregularly shaped lesions with linear or geometric outlines, predominantly found in areas of the body that are easily reachable by the patient.4 Patients with DA typically report the appearance of lesions, but are vague about their condition, and cannot clearly explain how the lesions developed. This is termed a ‘hollow history’, which is characteristic of patients with DA.5,6

In many cases, the onset of DA is associated with the presence of an identifiable psychosocial stressor or a coexisting psychiatric condition. Depression, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and borderline personality disorder are common psychiatric diagnoses in patients with DA. Skin lesions in DA can arise either consciously or during a dissociated state.4,7,8 When patients are unable to recognise their involvement in the development of the skin lesions, this leads to a classic denial of any responsibility for the pathogenesis of DA, and inability or unwillingness to disclose the origin of the lesions. Patients and their families are often resistant to the diagnosis initially, and can be hesitant to follow up with psychiatric or psychological services.9–11 As a result, dermatologists often find it difficult to approach treating patients with this condition.

DA poses a complex clinical challenge to clinicians, and there is a need to determine the optimal approach for management and treatment. Although there are many case reports published on DA, the review of published literature has revealed a limited number of case series, retrospective, or prospective studies on the topic. The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate the treatment and management of this complex condition.

METHODOLOGY

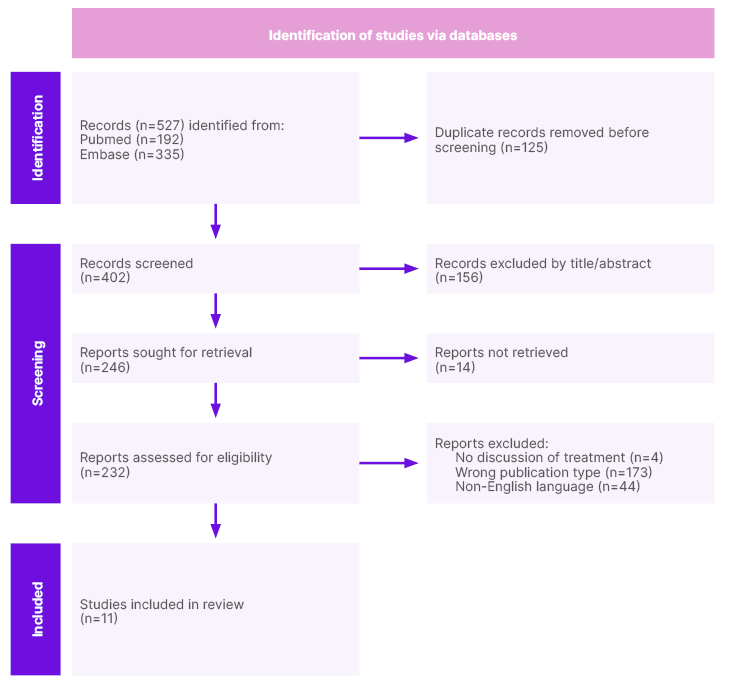

To analyse literature published up until the 5th of April 2023, the following search strategy was used on PubMed and Embase: Dermatitis artefacta OR factitious dermatitis OR factitial dermatitis OR artefactual skin AND treatment OR management OR therapy OR psychotherapy OR pharmacotherapy. Article reference lists were also examined. Studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: discussed the treatment and management of dermatitis artefacta; case series, systematic reviews, cohort studies, randomised controlled trials, cross-sectional studies, or case-controlled studies; and publication in peer-reviewed journals. Studies were excluded if published in a non-English language, or the wrong publication type (for example, case reports or letter to the editor). Included studies discuss the management of dermatitis artefacta, which differs from other types of self-inflicted cutaneous diseases such as excoriation disorder, trichotillomania, delusional parasitosis, and Munchausen syndrome. The initial review of studies was conducted in chronological order by one reviewer. Figure 1 provides a flow diagram illustrating the search process. Table 1 summarises the findings of the included studies.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of search process.

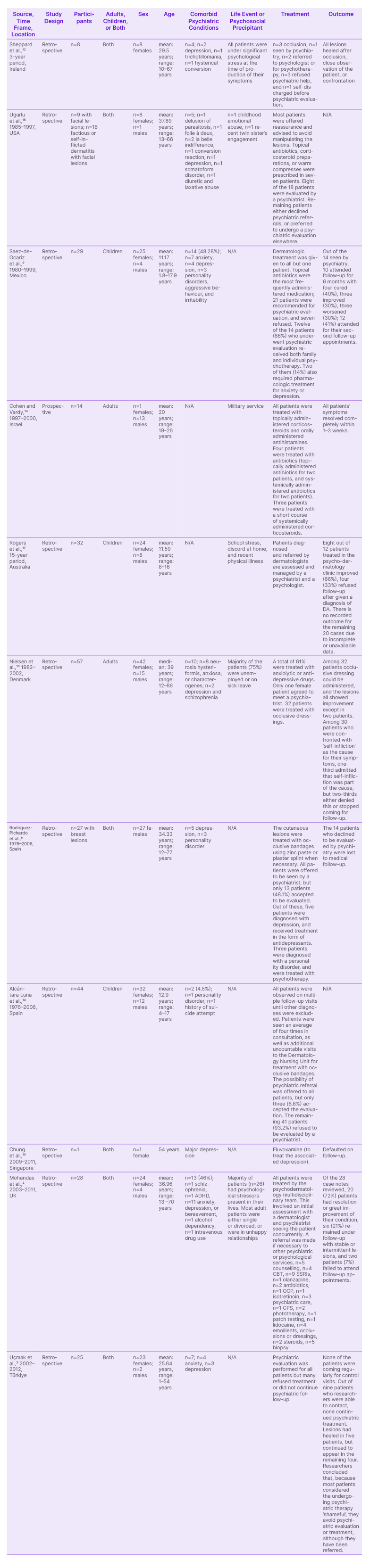

Table 1: Included studies in chronological order.

RESULTS

The authors’ search found 11 retrospective or prospective studies that discussed the treatment of patients with DA. Larger studies analysing the characteristics and management of DA date back to the 1980s. One retrospective case series published in 1986 reviewed the records of patients with psychogenic skin disease, seen in a clinical practice, over a 3-year period. Eight patients with DA were identified. All eight patients were females, with a mean age of 29.5 years (range: 10–67 years). Three of the eight patients were treated with occlusion. One patient was seen by psychiatry, two were referred to psychologists, three refused psychiatric help, and one self-discharged before psychiatric evaluation. All patients were under significant psychological stress at the time their symptoms began. Four patients had a formal comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, two patients had depression, one patient had trichotillomania, and one patient had ‘hysterical conversion’. All lesions healed after occlusion, close observation of the patient, or confrontation.12

A retrospective chart review from a 19-year period between 1980–1999 was conducted at the National Institute of Paediatrics in Mexico City, Mexico. There were 29 patients (25 females and four males) with a mean age of 11.17 years (range: 1.8–17.9). Out of these patients, 21 were recommended for psychiatric evaluation, but seven of them refused. Fourteen patients received a psychiatric diagnosis (seven had anxiety; four had depression; and three had personality disorders, aggressive behaviour, and irritability). Twelve of these patients were treated with psychotherapy, and two received pharmacologic treatment for their comorbid depression and anxiety disorders. Of the 14 patients who underwent psychiatric evaluation, only 10 patients were followed up for a period of 6 months. Of these 10 patients at follow-up, four (40%) were considered cured, three (30%) showed improvement, and three (30%) had worsening of their condition. The most commonly prescribed dermatologic treatment was topical antibiotics. Additionally, two patients treated with occlusion showed improvement in their lesions.9

There have been two retrospective studies published looking at subsets of 201 patients with DA, treated over a 30-year period, from 1976–2006, at the Department of Dermatology of the Virgen Macarena Hospital in Seville, Spain. The first study by Rodríguez-Pichardo et al.11 reviewed patients diagnosed with DA of the breast. Out of 201 patients diagnosed with DA, 27 had lesions affecting the breast. These patients were all female, with a mean age of 34.33 years. The skin lesions were treated with occlusive bandages, at times utilising zinc paste or plaster splints. Every patient was offered psychiatric evaluation, but only 13 patients (48.1%) agreed to be seen by a psychiatrist. Out of these patients, five received a diagnosis of depression treated with antidepressants, and three received a diagnosis of a personality disorder treated with psychotherapy. The other 14 patients (51.9%) declined psychiatric evaluation and were subsequently lost to follow-up.11

In the second study looking at a subset of the 201 patients with DA, Alcántara Luna et al.13 identified paediatric patients diagnosed with DA over the same 30-year time period. There were 44 children and adolescents, with a mean age of 12.9 years. On average, patients were evaluated four times before receiving a diagnosis of DA, and were also seen at numerous nursing visits for bandage treatments. All patients were given the opportunity for psychiatric referral; however, 41 patients (93.2%), the vast majority, declined to undergo psychiatric evaluation. Only three patients (6.8%) agreed to undergo evaluation. Out of these patients, two had psychiatric diagnoses, including a personality disorder and history of suicide attempt.13

A prospective study was carried out to investigate DA among members of the Israel Defence Force (IDF). Over a 3-year period, from 1997–2000, 14 soldiers were treated. There were 13 males and one female between the ages of 19–26 included in this study. For all patients, DA was characterised by an acute rash that was distributed in a linear pattern on the limbs and abdomen, and was associated with fever and systemic symptoms. The patients all denied deliberately causing the lesions, although eight patients acknowledged exposure to possible inflicting factors. All patients received topically administered corticosteroids, and orally administered antihistamines. Antibiotics were administered to four patients (two topically and two systemically). Three patients were given a short course of corticosteroids, administered systemically. In all cases, the rash resolved completely within a span of 1–3 weeks.14

In a study, Ugurlu et al.15 identified patients with factitious dermatitis at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA, treated between 1985–1997. Eighteen patients were seen for factitious dermatitis involving the periocular skin and face. Nine of these patients had received the specific diagnosis of DA. The majority of patients were provided reassurance, and received advice to avoid manipulating the lesions. Seven of the 18 patients were prescribed topical antibiotics, corticosteroids, or warm compressions. Eight of the 18 patients were seen by psychiatry at Mayo Clinic, but the rest turned down a referral for psychiatric evaluation, or expressed a preference to seek psychiatric care outside of Mayo Clinic.15

A retrospective study reviewed the records of 57 patients, over 20 years, from 1982–2002, in Denmark. DA was found to be 2.8 times more common in females compared to males, with 42 (74%) patients being female. The median age was 39 years (range: 12–86 years). A total of 61% of patients were treated with either anxiolytic or anti-depressive drugs. Ten patients (18%) had a psychiatric diagnosis. For patients who received occlusive dressings, lesions demonstrated improvement in 30 out of 32 patients. Among 30 patients where ‘self-infliction’ of the lesions was addressed with the patient, one-third acknowledged involvement in the development of the lesions. The rest of the patients either denied it, or discontinued the follow-up. Only a single patient agreed to be evaluated by psychiatry. The researchers concluded that psychological intervention appeared unhelpful because of the patient denying their involvement in creating the lesions.16

Recently, a retrospective study in Türkiye was performed to review the records of patients diagnosed with DA during a 10-year time period, from 2002–2012. Out of the 25 patients, there were 23 females and two males, with a mean age of 25.64 years (range: 11–54 years). Psychiatric evaluation was performed for all patients, and seven patients were found to have additional psychiatric conditions (four with anxiety disorders and three with depression). Nine of the 25 patients were able to be contacted by phone for follow-up. Five patients had resolution of lesions, while four continued to have lesions. Despite referral for treatment and further psychiatric evaluation, all of the patients avoided follow-up. The authors concluded that their patients perceived engaging in psychiatric treatment as ‘shameful’, and thus avoided follow-up and treatment.3

There were three studies included in this systematic review where patients were treated at a formal psychodermatology clinic or conference. Chung et al.10 performed a retrospective case series to review the records of patients seen in a bi-monthly psychodermatology conference jointly conducted by the Departments of Dermatology and Psychological Medicine at Changi General Hospital, Singapore, from November 2009–July 2011. The majority of patients were diagnosed with either a psychophysiologic disorder or a primary psychiatric disorder. One patient diagnosed with DA had comorbid major depression. The patient was started on fluvoxamine to treat the associated depression, but was lost to follow-up.10

A retrospective study by Rogers et al.17 reviewed patients referred to paediatric dermatologists at the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children in Sydney, Australia, over a 15-year period. Thirty-two paediatric patients diagnosed with DA were identified, including 24 females and eight males, ranging from 8–16 years in age. Most patients were treated at the hospital’s formal psychodermatology clinic that had opened 3 years prior. Patient data were incomplete or unavailable for many patients prior to this time. For the 12 cases of patients treated at the psychodermatology clinic, eight cases showed symptom resolution or improved functioning. Four patients declined to be evaluated by psychiatry or to follow up with dermatology, after being diagnosed with DA. The researchers suspected that DA in these patients were secondary to life difficulties such as medical illness, or stress at home or school. Most parents were hesitant to pursue additional psychological care once there was an improvement in the symptoms, suggesting that patients can have notable improvement due to changes in life situations, or the development of maturation, instead of directly from treatment directly.17

Similarly, Mohandas et al.2 performed a retrospective study to review charts of 28 patients diagnosed with DA, who had received care at a formal psychodermatology clinic in England, from 2003–2011. Most patients seen were female (24 female and four male), and ages ranged from 13–70 years. The vast majority of patients (n=26) endorsed psychosocial stressors. Thirteen patients (46%) presented with comorbid psychiatric conditions, which included diagnoses of anxiety, depression, and personality disorders. Patients were seen in the clinic by a multidisciplinary team with a dermatologist and psychiatrist, both evaluating the patient at the same visit. This collaborative approach also involved psychologists, nurses, and social workers. Twenty-six patients (93%) were considered successfully managed (defined as DA resolved or in remission), with only two patients lost to follow-up.2

DISCUSSION

The main strategies for DA management include building strong patient relationships, addressing skin symptoms, and providing extended psychiatric care with consideration of any relevant underlying psychosocial factors. The preferred initial treatment for patients is cognitive behavioural therapy or psychotherapy.6 Medical management of DA focuses on wound healing, preventing infection, and symptom control. The use of emollients, antibiotics, antifungals, and analgesia paired with suitable dressings or bandaging can promote the healing of lesions. Psychopharmacological treatment options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and antipsychotics.6 Most patients do not require surgery, although debridement may be beneficial in some cases of wound colonisation or abscess formation.18

Management should be personalised to each patient, with an emphasis on exploring any psychosocial stressors that may be contributing to the development of DA. Direct confrontation of the patient behaviours that led to the formation of the lesions is counterproductive, often leading to patients disengaging with medical care, and becoming lost to follow-up.

One approach to addressing the patient’s problems could be avoiding discussion of the exact mechanisms behind the development of the lesions, and instead emphasising the impact of stress on the development of the condition, as this may be more easily accepted by the patient. It also may be beneficial to acknowledge that the condition can create stress for the patient, and this can be used as a justification for introducing psychological therapy as a treatment option. Regardless of the approach, it remains crucial to address both treatment of the skin and the psychological aspects of DA.

The use of a multidisciplinary psychodermatology team for DA is important because many patients require psychological intervention to address the underlying cause of their behaviour, and psychiatric evaluation to manage any comorbid psychiatric conditions. The opening of formal psychodermatology clinics has allowed dermatologists to play a crucial role in diagnosing DA, excluding other diseases, and establishing effective communication with mental health providers. This approach is essential for building and maintaining patient trust because it minimises the likelihood of losing patients to follow-up, and allows for continuity of building and maintaining patient trust.

The prognosis of DA is influenced by various factors, such as the age of presentation, identification of any triggering stressors, pre-existing state of health, and any underlying psychological disorders. Positive long-term outcomes are seen in paediatric patients, who were diagnosed and treated at an early stage.9 In contrast, older patients, or those with significant comorbid psychological or medical conditions, may experience a more relapsing clinical course. To achieve sustained remission, ongoing follow-up is important for patients with DA, particularly among those who experience a pattern of relapse. The establishment of psychodermatology multidisciplinary teams can play a vital role in streamlining care for patients with DA.

LIMITATIONS

This review is subject to some important limitations. Despite some of the included retrospective studies having larger sample sizes, examining a rare psychiatric disorder with a low prevalence can be challenging. DA is diagnosed clinically without well-defined diagnostic criteria. In some cases, clinicians who diagnosed DA may not have excluded similar conditions, such as skin-picking disorder, malingering, or intentional self-harm. All included studies relied on either clinician interviews or medical chart reviews, without standardisation in patient evaluations. It is possible that certain comorbid psychiatric diagnoses may have been missed. Some studies included in this review have limited detail on treatments provided or patient outcomes. In particular, limited retrospective studies focused on psychopharmacology. In some studies, a significant number of patients were lost to follow-up, or had short follow-up intervals, giving limited data on long-term treatment outcomes for patients with DA. Finally, each study included in this review differs in design and outcome measures, which makes it challenging to establish definitive statistical conclusions.

CONCLUSION

DA is a complex psychocutaneous condition that can be challenging for clinicians to diagnose and manage. This is the first systematic review published on DA that highlights the treatment and management of this condition. The cornerstone of DA management is creating a safe and trusting atmosphere during the patient visit, where clinicians can focus on understanding why a patient has the condition, rather than delving into the mechanisms of how the lesions were created by the patient. A non-judgmental and non-confrontational attitude on the part of the physician is warranted in seeing these patients.

Medical treatments can promote the healing of skin lesions, and facilitate the management of symptoms. Psychological and psychiatric treatments can help address underlying psychosocial stressors for the condition. This systematic review found better reported outcomes among follow-up patients treated in psychodermatology clinics. This suggests that multidisciplinary teams comprised of dermatologists, psychiatrists, and psychologists working together can offer optimal care for patients. Further research is needed to better evaluate the management options and long-term treatment outcomes for patients with DA.