Abstract

Background: The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has selected 988 as the number for mental health crisis and this came into effect in July 2022. It is not clear how aware psychiatric patients are of this event, and how much impact this will have on outpatient psychiatric care.

Methods: Prior to the introduction of 988, the authors performed a study of patients attending the outpatient psychiatric clinic at the department of psychiatry’s outpatient services. The study comprised of a one-page questionnaire to acquire qualitative and quantitative data on patients’ knowledge and acceptance of the change in the access of the suicide prevention number.

Results: A total of 74 outpatient psychiatric patients were surveyed during the course of the study. Most (87.8%) of surveyed individuals denied memorisation of their local mental health crisis or suicide prevention hotline number. Of the 24 individuals who reported previously having called a crisis hotline, over one-third (37.5%) reported difficulty remembering or finding the number. In response to the introduction of a three-digit crisis hotline number, 63.5% (47) of surveyed individuals reported both increased confidence in receiving prompt, effective psychiatric care, and greater likelihood of seeking help with the three-digit number. Finally, 77.0% (57) stated that a three-digit number would be more easily remembered than current options. The majority (89%) of responders were not aware of the 988 hotline number.

Conclusion: Patients believe the 988 number will be a helpful tool in their care. One year after its introduction, awareness of 988 has barely changed.

Key Points

1. Psychiatric patients believe that the new National Mental Health Hotline Number, 988, is easy to remember and is a good idea.

2. Prior to the release of 988, only 11% of patients were aware of its existence. One year after the release of 988, only 17% know it is active.

3. These data indicate that better advertising of the existence of 988 is necessary for it to be fully successful.

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a significant cause of death globally. Every year, 800,000 people take their own life, making up 1.4% of all global deaths.1,2 Suicide ranks as the 18th leading cause of death across the general population, and the second leading cause of death among people aged 15–29 years.3 In the USA, suicide is the 10th leading cause of death, and has increased by 30% since 1999.4 Veterans and youths are experiencing the greatest increased rates.5-8 Additionally, an estimated 9.3 million adults in the USA annually have thoughts of suicide.4 Key risk factors for suicide include an underlying illness, ongoing stressors, a sense of hopelessness, and other complex personal and biological factors.2,9 Suicide prevention is the goal, and can be achieved through psychological interventions,10 medication,11,12 or physical interventions (e.g., hospitalisation).12,13 However, for any of these interventions to work, at-risk patients must

first be identified.

Suicide hotlines appear to be an effective strategy.14-17 A National Suicide Prevention Lifeline was established in 2005, as part of a country-wide strategy to reduce suicide rates and support individuals in crisis. Until 2022, the national number was 1-800-283-TALK (8255). In 2020, it was accessed by more than 3.5 million callers.18 Nonetheless, over 80% of mental health consumers feel that access to telephone triage services is difficult.19 In August 2018, the Congress of the Federal Government passed HR 2345, the National Suicide Hotline Improvement Act, which directed the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to study adoption of a three-digit number to serve as a single national suicide prevention hotline number.20 In October 2020, Congress passed the National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020 (S2661), which designated 988 as the “universal telephone number for the purpose of the national suicide prevention and mental health crisis hotline system operating through the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and through the Veterans Crisis Line.”21 President Donald Trump signed this into law in October 2020.22 In July 2022, 988 became a nationally available number, and replaced 1-800-283-TALK (8255). It will also be active in Canada in the near future. The original number was immortalised in a song by rapper Logic, which was performed at MTV’s Video Music Awards in 2017, and the Grammy Awards in 2018. Within the 34 days following these performances, calls to the crisis line increased by 6.9% (a significant increase above routine use, P<0.001), and completed suicides decreased by 5.5% (P=0.02).23 This experience highlights two important points for the success of a suicide hotline: suicide awareness, and knowledge of the suicide hotline number. The authors set out to investigate the level of awareness and ease of number recognition in a population of psychiatric patients at risk of developing suicidal ideation.

METHODS

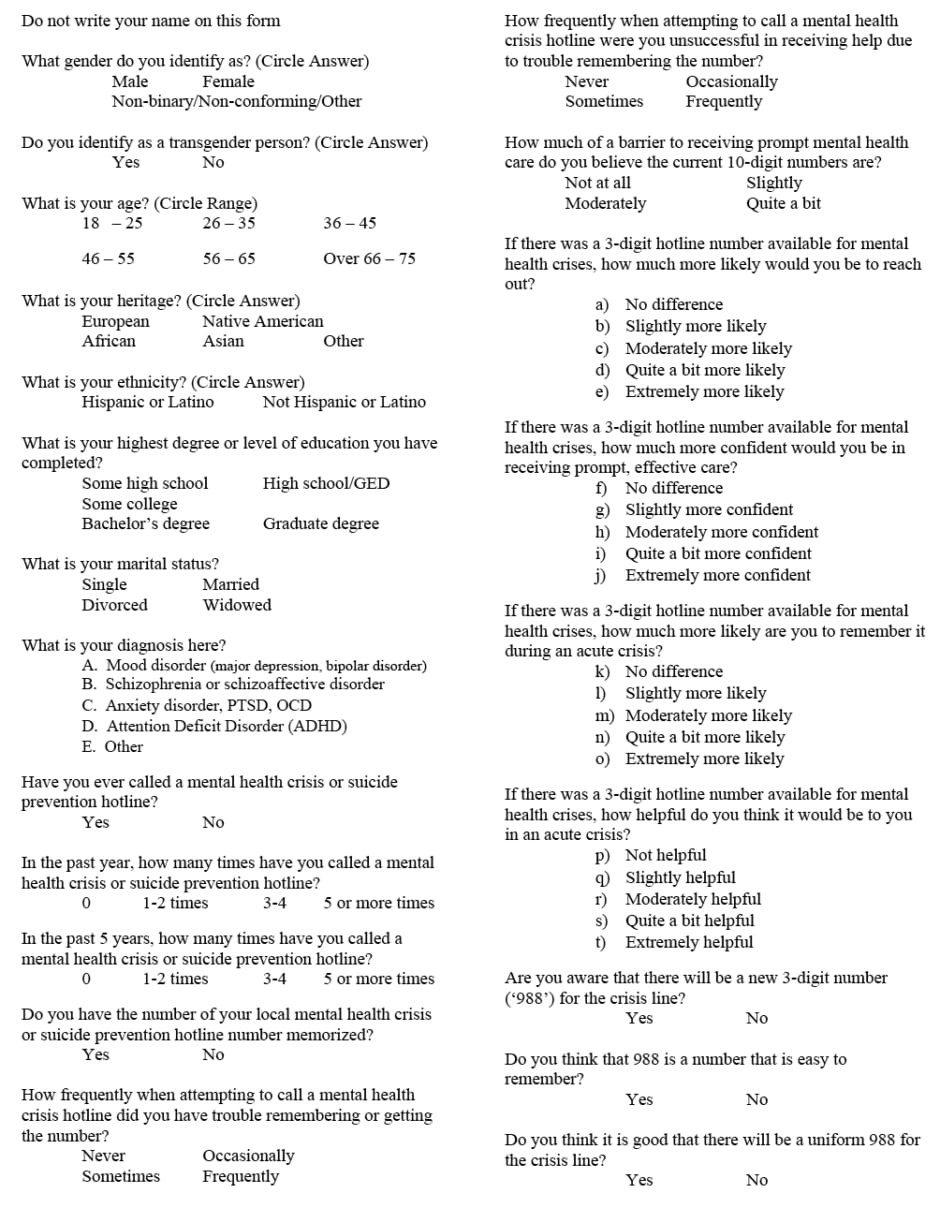

This study was performed prior to the introduction of 988. The authors recruited patients attending the outpatient psychiatric clinic at the Department of Psychiatry’s outpatient services. The majority of these patients had participated in previous studies, and knew that research protocols were frequently performed in the clinic they attended. Most patients had received care at this clinic for over a decade, had a mood disorder, and generally lacked an active substance use disorder. The study comprised of a one-page questionnaire to acquire qualitative and quantitative data on patients’ knowledge and acceptance of the change in the suicide prevention number (Figure 1). The data were evaluated quantitatively and qualitatively. Continuous variables were examined with non-paired, two-tailed t-tests. Categorical data were examined with the χ2-test.

Figure 1: Questionnaire used in the study.

GED: general educational development; OCD: obsessive compulsive disorder; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder.

RESULTS

The majority of subjects approached agreed to participate, with a small number of patients reporting time constraints as the reason for not participating. The fraction of patients who refused to participate was not tracked. Of the 74 psychiatric outpatients surveyed during the 6-month course of the study, 78.4% had a primary diagnosis of a mood disorder (n=58), 18.9% had schizophrenia or a schizoaffective disorder (n=14), and the remainder did not provide that information. Furthermore, 32.4% of individuals (n=24) reported calling a crisis hotline in the past. Of all surveyed individuals, 87.8% (n=65) denied memorisation of their local mental health crisis or suicide prevention hotline number. Of the 24 individuals who reported having previously called a crisis hotline, over 37.5% reported difficulty remembering or finding the number.

In response to the introduction of a three-digit crisis hotline number, 63.5% of surveyed individuals (n=47) reported increased confidence both in receiving prompt and effective psychiatric care, and a greater likelihood of seeking help when a three-digit number was available. Furthermore, 77% of patients (n=57) stated that a three-digit number would be more easily remembered than current options.

Prior to this study, 89% (n=66) of survey responders were not aware of the new federally approved 988 hotline number. At completion, 100% of participants both reported that 988 is an easy number to remember and approved of its choice for the national crisis line.

DISCUSSION

The current Lifeline number receives over 3.5 million calls annually. With the introduction of 988, a significant fraction of 911 calls are expected to be diverted to 988 to be managed by Lifeline. Vibrant (Vibrant Emotional Health, New York, USA), the non-profit company that runs the Lifeline service, estimates that over the first 5 years of 988 service, there will be approximately 4–5 million additional annual calls to 988, due to this diverted volume. More importantly, the availability of a simpler number is expected to result in an additional 4 million annual calls, exceeding the current use of the 10-digit Lifeline number and 911.18

Over the first year since its release in July 2022, there have been over 5 million contacts with 988, including 3.6 million phone calls, and more than 600,000 texts and 740,000 chats.24 However, a recent poll performed by the National Alliance of the Mentally Ill (NAMI) found that awareness of the availability of the 988 number is still low (17%), although 63% of Americans reported hearing about it.25

In this study, over one-third of people who had previously used a crisis number (37.5%) reported some difficulty in accessing the available 10-digit numbers.18 All participants in this survey believed that a three-digit number was a good idea, and 77% reported that 988 was an easy-to-recall choice.18 The reason for creating a three-digit crisis hotline number is to facilitate access to mental health services; however, patients must be aware of it. The authors’ study was performed prior to the introduction of 988, but after the law had been signed by President Donald Trump; yet, 89% of surveyors were not aware of its existence. One year later, the situation has changed only minimally. The increase in the use of the original Lifeline number following its mediatisation during the performance by Logic demonstrates that advertising of 988 will be necessary for society to fully experience the benefit of this new number.21 Additionally, a public knowledge campaign should persist. It may be reasonable for psychiatric providers, or even general practitioners, to have posters in their offices advertising 988. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has free resources available for all healthcare providers, including magnets, bumper stickers, wallet cards, posters, and other materials.26 However, they may also consider the utility of sponsoring Internet advertisements targeting individuals searching suicide-related items.

This study has some limitations. The sample is small, with a mood disorder overrepresentation (78.4%). Additionally, individuals were sampled during their outpatient psychiatric visit; thus, acute distress was already being addressed in their visit. Individuals in acute distress were not sampled here, and their survey responses may have been somewhat different in that state. Similarly, the study did not examine toxicology laboratory values, with all patients clinically sober at the time of the study. Drug or alcohol use may play a role in the ability to recall a three-digit number. The questionnaire used (Figure 1) was not validated in any way. Furthermore, it was offered to patients as part of their outpatient visit, but was not exhaustive (i.e., the authors did not seek out patients who were not scheduled, which may have altered the generalisability of the study). This may have reduced reliability. Finally, the study was performed prior to the rollout of the 988 number. Given that the survey itself was a way to educate patients regarding 988, a second survey would have been more informative about the implementation of 988. Although the study did not re-examine the patient population, it did compare the pre-rollout data with the recent NAMI study.25 The two samples are not interchangeable, but the similarity in the pre-study non-awareness is alarming, particularly in the NAMI data.

Despite these limitations, the current study finds that all patients were supportive of the creation of a 988 number, and most believed it would ease the use of the crisis Lifeline number. This study was performed prior to the execution of the 988 number, but after the law of its creation was signed by President Donald Trump. Only 11% of patients were aware of its existence, which demonstrates that, for 988 to be effective, advertising is necessary. Although nearly two-thirds of Americans have now heard about 988, only 17% know it is active,25 which is barely greater than the 11% observed 1 year ago. Better public education is therefore needed.