Abstract

Renal artery angioplasty and stenting remain controversial in managing atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Landmark trials (ASTRAL and CORAL) failed to show superiority over optimal medical therapy, yet design limitations, including the exclusion of high-risk patients, the employment of variable imaging modalities, and the utilisation of non-standardised protocols, undermined both studies and limited their applicability. Since these trials, the RADAR trial was prematurely terminated, echoing prior findings, but in a small cohort of patients. Of six major RCTs since 1998, most excluded patients with flash pulmonary oedema, refractory hypertension, or rapidly declining renal function. Meta-analyses report reduced antihypertensive burden after renal artery revascularisation, particularly in those with severe or resistant hypertension, but without clear benefit for mortality, renal function, or adverse events. Lower-level evidence from case series highlights success in select high-risk situations (recurrent pulmonary oedema, progressive renal decline, or complex anatomy). Current American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/American Heart Association (AHA) and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines endorse revascularisation in specific contexts (Level B–C evidence). Given the limitations of past RCTs, there is a need for robust new RCTs in appropriate patient populations to conclusively determine the role of renal angioplasty and stenting in atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis.

Key Points

1. Both the ASTRAL and CORAL RCTs excluded high-risk patient cohorts (flash pulmonary oedema, refractory hypertension, rapidly declining renal function), underrepresented patients with severe renal artery stenosis (RAS), relied on variable imaging modalities for RAS diagnosis, and lacked procedural consistency, reducing broad applicability in real-world clinical practice.2. Despite being a relatively common condition, the role of RAS revascularisation remains highly debated. High-risk subgroups remain underrepresented in the current evidence base, with limited low-level recommendations for offering treatment from the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/American Heart Association (AHA) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines (Level B–C).

3. A robustly powered, multicentre RCT targeting severe RAS (>70% stenosis, ideally confirmed by pressure gradients and with core lab adjudication) and including patients who are high-risk with flash pulmonary oedema and rapid decline in renal function, is important to definitively assess the clinical benefit of angioplasty and stenting in RAS.

INTRODUCTION

Renal artery stenosis (RAS), which is most often atherosclerotic in aetiology (90% of cases), remains a contentious indication for endovascular therapy. Its prevalence varies from approximately 1% in mild hypertension to 14–24% in resistant hypertension,1 and it accounts for 2–5% of cases of secondary hypertension.2 In advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) populations, rates may reach 5–22%.1 Beyond hypertension, atherosclerotic RAS contributes to flash pulmonary oedema and acute coronary syndromes.2 Fibromuscular dysplasia and rarer vasculopathies make up the remaining 10% of RAS encountered in clinical practice.1This review outlines current evidence for renal angioplasty and stenting in atherosclerotic RAS, critically appraises landmark trials, and highlights knowledge gaps to guide future research.

KEY TRIALS IN RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS ANGIOPLASTY AND STENTING

The ASTRAL trial was a multicentre, randomised, and unblinded trial comparing angioplasty ± stenting versus medical therapy in atherosclerotic RAS (N=806).3 No difference was seen in renal function, blood pressure (BP), or survival at a median follow-up of 33.6 months. However, nearly 41% of participants had <70% stenosis, and those most likely to benefit, such as patients with flash pulmonary oedema, refractory hypertension, or rapidly declining renal function, were largely excluded.3-6 Patient inclusion required ‘clinical uncertainty’ about benefit, undermining ‘investigator equipoise’.5,6 There was no central core laboratory to validate RAS diagnosis or severity,4,5 and imaging modalities, including digital subtraction angiography, CT, magnetic resonance angiography, and duplex renal ultrasonography, varied and lacked standardisation amongst recruitment sites. Operator technique and variability in angioplasty and stenting further compounded the lack of standardisation.7 In August 2024, long-term follow-up data (median: 56.4 months) again showed no overall advantage of revascularisation, though lower risk enrolment likely underpowered the detection of subgroup benefits, with the authors suggesting further trials in high-risk populations.6

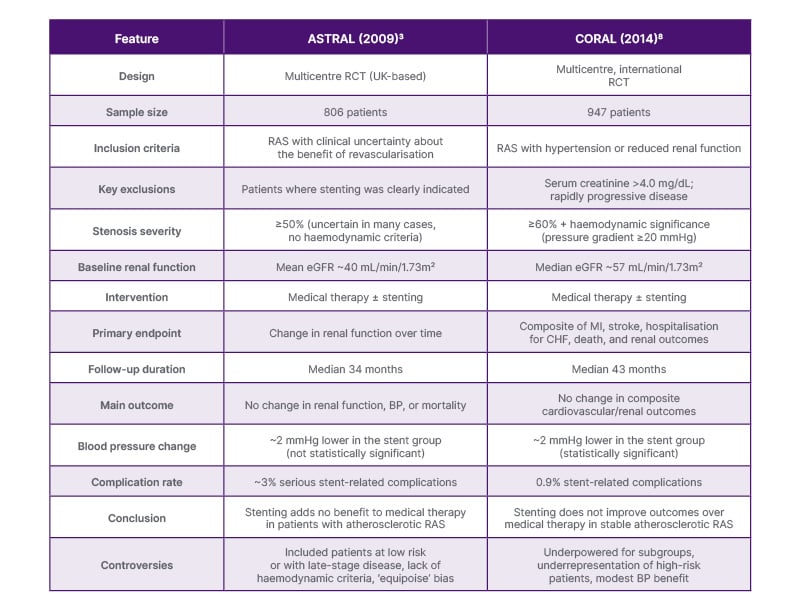

Following this, the CORAL trial randomised 947 patients with atherosclerotic RAS and hypertension or CKD to stenting plus medical therapy versus medical therapy alone, finding no difference in major cardiovascular or renal outcomes over a median of 43 months.8 Critics note that by excluding fibromuscular dysplasia, non-ischaemic CKD, and lesions unsuitable for a single stent, and by altering systolic BP targets mid-trial,9 it underrepresented the highest-risk patients. Although a modest 2 mmHg greater BP reduction was seen in the stenting arm,8 aggressive background therapy and inconsistent pressure-gradient measurements (only 53% of the stent arm versus 34% of the medical arm) likely blunted any real-world benefit.10 Imaging modalities varied despite core laboratory oversight,7,11 and a 2023 subgroup analysis suggested improved event-free survival in those with renal function gains post-stenting.12 Together with ASTRAL’s limitations, these findings underscore the need for new RCTs targeting high-risk RAS cohorts. Table 1 summarises the key highlights of the ASTRAL and CORAL trials.

Table 1: Summary of the ASTRAL and CORAL trials.3,8

BP: blood pressure; CHF: congestive heart failure; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; MI: myocardial infarction; RAS: renal artery stenosis.

Two earlier RCTs, DRASTIC13 and STAR,14 also failed to demonstrate a clear benefit in revascularisation. In DRASTIC, primarily balloon angioplasty (without routine stenting) reduced antihypertensive use (mean of two versus three drugs), but saw high crossover (approximately 44%) from medical to angioplasty arms due to refractory hypertension. A post-hoc review found 10 patients with mild <50% stenosis, calling into question the diagnosis of renovascular hypertension15 in many participants, and thus, the conclusion that angioplasty has little advantage over antihypertensive-drug therapy.13 Similarly, the STAR trial enrolled mostly moderate stenoses and excluded high-risk patients, finding no significant preservation of renal function with stenting plus medical therapy versus medical therapy alone.14,16

The HERCULES study was a single‐arm, prospective, multicentre trial of the Herculink Elite® (Abbott, Santa Clara, Illinois, USA) stent for the treatment of RAS. HERCULES enrolled 202 patients with ≥70% RAS and uncontrolled hypertension. At 9 months, the mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) decreased from 162±18 mmHg to 145±21 mmHg (p<0.0001) in 77.5% of patients, with restenosis rates of 10.5%.17 At 36 months, SBP reductions persisted (146±21 mmHg; p<0.001), with low restenosis (<10%) and periprocedural complication rates (<4%). The majority (74.3%) maintained SBP improvement, particularly those with baseline SBP ≥180 mmHg (mean: −46 mmHg).18 Although limited by its non-randomised design and predominantly White cohort, HERCULES suggests durable BP benefit in severe RAS and supports the need for a rigorously controlled RCT in high‐risk patients.17

CURRENT DATA SINCE THESE TRIALS

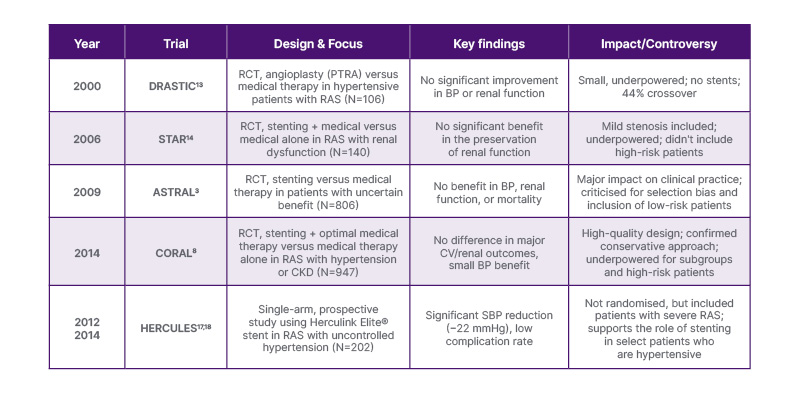

Since CORAL,8 no new RCTs have definitively assessed revascularisation in atherosclerotic RAS. The RADAR trial19 was halted in 2017 after enrolling only 86 of the 300 planned patients with ≥70% de novo RAS. It showed no benefit of stenting plus medical therapy over medical therapy alone, but is likely to have been underpowered given the low number of participants recruited. Slow patient enrolment was likely reflective of its stringent inclusion criteria.19 Thus, the contemporary evidence base remains confined to seven trials from 1998–2014 (Table 2): EMMA,20 Scottish and Newcastle Renal Artery Stenosis Group study,21 DRASTIC,13 STAR,14 ASTRAL,3 CORAL,8 and HERCULES.17 No further major trials have been identified at the time of this review.

Table 2: Timeline of key renal artery stenosis trials and studies.

BP: blood pressure; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CV: cardiovascular; Herculink Elite®: Abbott, Santa Clara, Illinois, USA; PTRA: percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty; RAS: renal artery stenosis; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Meta-analyses of ASTRAL and CORAL data suggest stenting may modestly lower BP or reduce antihypertensive requirements, especially in severe or refractory hypertension, within 2 years, but without a clear impact on mortality, renal decline, or serious adverse events.22,23 Numerous case reports24-29 and small cohort studies30 document successful outcomes in high-risk lesions excluded from these major RCTs. Early innovations, such as intra-procedural elamipretide infusion, have shown promise in improving the estimated glomerular filtration rate and lowering BP in a small Phase IIa trial,31 underpinning the potential for evolving techniques to reshape future study outcomes.

CURRENT INDICATIONS

The 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/American Heart Association (AHA) Peripheral Artery Disease guidelines32 grade all RAS revascularisation recommendations as Level B or C evidence. The guideline suggests percutaneous angioplasty ± stenting may be considered in asymptomatic bilateral or solitary-kidney RAS with haemodynamic significance (Level C), but is unproven in asymptomatic unilateral disease. Revascularisation is supported (Level B) for progressive kidney disease, bilateral RAS, or RAS in a solitary functioning kidney.32 It is also a reasonable treatment (Level B) for recurrent pulmonary oedema, unstable angina with significant RAS, and recurrent, unexplained congestive heart failure. The 2017 ESC/ESVS Peripheral Artery Disease guidelines advise against routine revascularisation in atherosclerotic RAS (Level A) but support angioplasty ± stenting for recurrent cardiac failure or flash pulmonary oedema (Level C).33 Both ACC/AHA and ESC stress individualised clinical judgement on a case-by-case basis.

Case reports highlight successful interventions in high-risk scenarios such as recurrent pulmonary oedema,34 including Pickering syndrome35 and progressive renal decline.36 Such cases highlight that it would be remiss not to reiterate the criticisms of ASTRAL and CORAL and their lack of inclusion of such patients. Importantly, it should be noted that guidelines often lag behind available evidence, and indeed, both guidelines are derived from data pre-2017.

GAPS IN KNOWLEDGE

Despite extensive study, the authors lack RCT data in the highest-risk RAS subgroups: >70% stenosis or haemodynamically confirmed stenosis with pressure measurements, bilateral disease, rapidly declining renal function, and flash pulmonary oedema. HERCULES suggests promising long-term BP control and safety data in patients with severe RAS, but its findings require confirmation in a rigorously controlled trial targeting these high-risk cohorts.

CONCLUSION

More than 10 years after ASTRAL and CORAL, the role of renal angioplasty and stenting for atherosclerotic RAS remains uncertain. Existing RCTs suffer from selection bias and variable lesion grading, and they exclude patients most likely to benefit from revascularisation. However, limited evidence does exist and suggests benefit in appropriate patients (HERCULES, subgroup analysis of CORAL). There is a need for a contemporary, high-quality RCT, free of the issues above, to reach a definitive conclusion regarding renal artery revascularisation for the treatment of atherosclerotic RAS in properly defined patient populations.