INTRODUCTION

Cancer evolves through layers of change: mutations in DNA, shifts in gene regulation, altered cell behaviour, and dynamic interactions with the immune system. Each tumour follows its own trajectory through this landscape. Computational models are beginning to capture parts of this complexity, identifying how cancers progress and respond to therapy. These tools, however, remain narrow: one analyses DNA, another reads pathology slides, and another predicts immune recognition. They are designed in isolation and form a patchwork of insights that falls short of explaining the full architecture of cancer biology.

Progress now depends on systems capable of learning across biological scales. Foundation models present one such opportunity. Trained on extensive and heterogeneous datasets, they may connect a single molecular change to its downstream effects. Realising this potential requires computational capacity beyond conventional research clusters, which makes access to national supercomputing infrastructure decisive.

The UK is building this capacity. Facilities such as Dawn, a national research supercomputer in Cambridge, UK, and Isambard-AI in Bristol, UK, represent strategic investments in computational power, meant to enable biomedical foundation models that operate at breadth and depth.1 With these resources, researchers can move beyond predicting one event in isolation to tracing how a genetic mutation cascades through a cell, into a tissue, and ultimately shapes an immune response.

A compelling test case is the concept of personalised cancer vaccines. Their design depends on predicting which tumour fragments can be recognised by T cells. Right now, those pipelines often focus on modelling specific components of cancer immunity, and this results in a small fraction of predicted vaccine targets inducing measurable responses in patients.2 A foundation model could change this by training on richer data that could capture the full cascade from mutation to immune activation.

This feature makes the case for such an approach. The claim is not that computation alone will solve the challenge of cancer vaccines; rather, supercomputing-scale models offer the integration necessary for faster and more reliable progress. To realise the potential of personalised immunotherapy, the field will need to build models that reflect the complexity of cancer biology and, at a scale, commensurate with the challenge.

PROGRESS IN TASK-SPECIFIC TOOLS HAS SET THE STAGE FOR CROSS-CANCER, CROSS-MODALITY MODELLING

Over the past decade, task-specific tools have been designed that show that cancer leaves patterns that algorithms can detect. In pathology, deep learning models trained on lung and colorectal cancer slides have matched expert pathologists in classifying tumours.3 Significantly, they can infer genetic features, detecting microsatellite instability, a sign of defective DNA repair that guides treatment, or predicting the likelihood of an EGFR mutation, which indicates potential benefit from targeted drugs.3 In genomics, similar models have helped predict patient prognosis and shown which early-stage patients can safely avoid chemotherapy.4 These cases highlight that information from one level of cancer biology can identify information about another.

Immuno-oncology poses an even tougher challenge: predicting which tumour fragments (peptides) displayed on the cell surface the immune system will recognise. Tools have improved our ability to predict whether a mutated peptide will bind to a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecule, a key step for personalised vaccine design.5 Yet, these models expose the limits of narrow design: in early-phase trials, approximately one in five predicted that peptides generate measurable T cell responses.2 Many ‘strong’ binders never elicit immunity, while some lower-ranked peptides prove unexpectedly effective. Still, the fact that vaccines can be designed this way shows that computational tools can capture part of an immensely complex process once thought beyond prediction.

When predictions are made in isolation, they overlook how molecular change, tissue context, and immune activity depend on each other. In today’s vaccine pipelines, this separation means that mutations that appear promising at one stage may fail for different reasons, and thus uncertainty compounds. Task-specific tools suggest that cancers leave reproducible signatures, and that those signatures can be extracted with sufficient accuracy to influence patient care. They also imply that improvements within single-modality, single-function predictors will reach a ceiling, because no one data type contains enough context to explain outcomes on its own. To overcome this, models can learn from multiple kinds of information at once.

MULTI-MODAL APPROACHES MAKE IT POSSIBLE TO CONNECT MOLECULAR FEATURES WITH OUTCOMES

A foundation model is a system trained on large and diverse datasets to learn patterns that can be adapted across many tasks. In cancer research, this refers to a model that can simultaneously take in DNA sequences, gene expression profiles, protein maps, tissue images, and immune responses. Instead of treating each separately, the model builds a shared representation that links them, mirroring cancer biology as an interconnected system.

AlphaGenome (Google DeepMind, London, UK) demonstrates this approach.6 Traditional genomic models tackle one narrow task at a time, such as predicting gene splicing or RNA levels, without showing how one change affects another. AlphaGenome instead reads raw DNA and is trained to predict many biological readouts at once. In doing so, it learns dependencies: how a single mutation might alter splicing or change RNA abundance. In head-to-head comparison, AlphaGenome appears to consistently outperform specialised tools by learning these connections across layers of biology.6

Foundation models are not magic bullets. They can be expensive to train, difficult to interpret, and require infrastructures that most cancer centres do not yet have.7 Just as importantly, their biological scope is incomplete: models like AlphaGenome miss long-range interactions and tissue-specific effects, which are important in cancer. There are areas where narrow tools remain highly effective; predictors of binding affinity, for example, already approach the limits of lab precision.8 The value of foundation models lies in linking molecular features to functional outcomes that matter for patients.

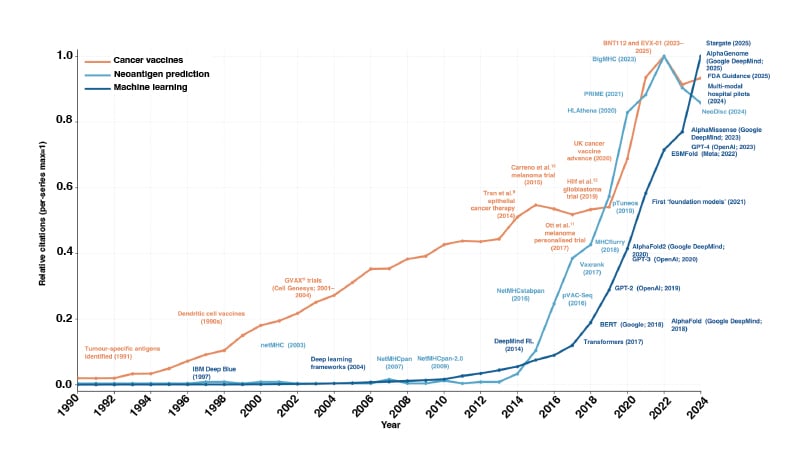

Cancer vaccines highlight the need for this. Current pipelines assess whether a mutated peptide binds to an HLA molecule, is presented by tumour cells, and elicits an immune response. These steps reflect decades of immunology, and the models that implement them have advanced rapidly.2 What has changed is the convergence of vaccine development, neoantigen research, and machine learning, which now makes integrated modelling feasible (Figure 1).

Figure 1: PubMed citation trends from 1990–2024 across three domains: cancer vaccines (orange), neoantigen prediction (teal), and machine learning (blue).

Counts of indexed publications were retrieved separately for each domain and normalised to the maximum annual value within that series, allowing direct comparison of relative growth over time. Representative methodological advances are annotated.

Cell Genesys (now acquired by Genzyme): Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA; Google DeepMind: London, UK; Google: Mountain View, California, USA; IBM: Armonk, New York, USA; Meta: Menlo Park, California, USA; OpenAI: San Francisco, California, USA; pVAC-Seq: personalised Variant Antigens by Cancer Sequencing; RL: reinforcement learning.

Foundation models can be trained from multi-modal data, including immunopeptidomics, T cell recognition, and clinical outcomes. By embedding peptides in their biological context, such as how much they are expressed, whether tumour cells develop strategies to stop displaying them, and what the microenvironment looks like, models could learn why the same peptide would work in one patient, yet fail in another. This creates the opportunity to move beyond ranking individual binders, towards selecting sets of peptides that work together to drive durable immune responses, and to adapt as tumours evolve across sites and microenvironments.

Single-function models will remain important as clear benchmarks, and foundation models can allow the field to move from fragments to systems. In cancer vaccines, where current tools explain only part of the clinical signal, this transition may be the most promising way to build predictions that align with what patients need.

SUPERCOMPUTING EXTENDS THE REACH OF INDIVIDUAL CLUSTERS

If foundation models offer a way to move from fragments to systems, supercomputing provides the infrastructure to make that transition feasible. Linking genetic changes, protein expression, tissue structure, and immune outcomes requires significantly more capacity than conventional bioinformatics clusters were built to deliver. That capacity is now arriving. In the UK, new national facilities, including Dawn, Isambard-AI, and the forthcoming Stargate UK infrastructure partnership, offer the scale to train foundation models.

Supercomputing allows researchers to work with larger datasets, as well as tackle more ambitious objectives: predicting peptide stability, immune recognition, and functional outcomes. Supercomputing also enables iteration at the pace of real-world medicine. A personalised vaccine cannot wait months for a model to be retrained; national facilities make it possible to adapt quickly as new data emerges, keeping timelines aligned with clinical need.

National supercomputing offers capabilities that are hard to achieve through other approaches. Cloud services can scale, though at unsustainable cost and with uneasy questions about data sovereignty. Federated approaches are elegant in theory, yet fragile when faced with the messy, multi-modal datasets that cancer research depends on. While more efficient model designs will help, they cannot replace the force generally needed to capture biology across scales. National facilities provide predictable access to compute.

This scale brings challenges. Training large models requires data to be linked across hospitals, protected appropriately, and made available in formats that can support large-scale training. Concentrating compute in few national facilities raises practical questions of access and prioritisation, such as who gets to run which experiments, and on what timescales? These concerns are real, yet surmountable. Facilities are experimenting with allocation models that balance fairness with clinical urgency and creating training programmes so that biomedical researchers can design and run workloads.1 In practice, the challenges are less barriers than design constraints.

Beyond computation, NHS data sit across trusts with distinct governance arrangements. The UK is addressing this through Trusted Research Environments (TRE), which allow analysis without data leaving institutional control. Programmes such as the Federated Research Infrastructure by Data Governance Extension (FRIDGE) programme deploy NHS-compliant TREs directly onto national supercomputers, enabling large-scale training while preserving local governance.13 Public trust underpins this work, with patient involvement built in and all outputs treated as decision-support tools requiring validation before clinical use.

THE UK CAN PROVIDE A TEMPLATE FOR HOW SUPERCOMPUTING ADVANCES DELIVER PATIENT BENEFIT

The UK Cancer AI & Supercompute Project is a clinical research consortium that has received national supercomputing access from the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. Its purpose is to evaluate whether national-scale computing can help direct the immune system to recognise and eliminate cancer to make safer, more precise, and more effective treatments. Using Dawn, the consortium is training foundation models on data from tens of thousands of tumours to model whole-patient immune responses rather than isolated peptide interactions. This brings together researchers, physicians, patients, and policymakers to test whether coordinated infrastructure can accelerate discovery in cancer immunotherapy.

The consortium approaches this through three priorities. First, integrating genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and immunopeptidomic data within a single model, so that predictions follow the cascade from mutation to immune recognition. Second, treating vaccines as multi-peptide systems, reflecting how immune responses arise from interactions among sets of peptides. Third, benchmarking performance across diverse HLA alleles, addressing the overrepresentation of European populations in existing datasets. Evidence from longitudinal pan-cancer cohorts on immunotherapy shows why this matters, as predictive models can only improve when trained on data that reflect authentic patient trajectories.14

Looking ahead, strong models are necessary but not sufficient. The bigger challenge is making them usable at a national scale. That means enabling patient data to be linked across NHS trusts in ways that are technically workable and trusted in practice. Much of the work sits in the details: aligning data standards, handling consent for identifiable samples, and ensuring governance processes function smoothly rather than as obstacles. If these foundations are in place, national supercomputing can be paired with TREs and clinical oversight to support safe, fair deployment and real clinical impact.

This work sits within the UK’s AI Research Resource programme, which is investing over one billion GBP to expand national compute capacity by a factor of 20 by 2030. Through this programme, the consortium received 10,000 graphics processing unit hours on Dawn, providing the scale needed to train models on large tumour datasets within clinically relevant timelines.

This project is a test case for aligning national-scale infrastructure with a specific therapeutic objective. Similar efforts are emerging elsewhere, including the USA’s Genesis Mission, which brings together federal datasets and supercomputing to support AI-driven work in health. The outcomes of these projects will indicate whether foundation models can improve candidate selection, accelerate vaccine design, and extend therapeutic benefits across patient groups, with potential impacts on survival, the pace of development, and the precision of treatment. Beyond vaccines, these lessons will help clarify both the potential and the limitations of supercomputing in translational research, and highlight where alternative strategies or complementary investments may be necessary.

CONCLUSION

The next frontier in cancer care will not be won by drugs or datasets alone, but rather by the ability to connect them through systems powerful enough to reflect the reality of human biology. The UK has placed itself at the centre of this by bringing together supercomputing and clinical ambition.