BACKGROUND

Synesthesia, a condition where stimulation of one sensory pathway involuntarily triggers another (e.g., seeing colors when reading letters), has been a longstanding topic of neurological curiosity. Grapheme-color synesthesia (GCS), where individuals associate letters and numbers with specific colors, is one of the most common forms. This phenomenon, while benign, is believed to provide insight into cortical connectivity and cross-modal sensory processing. Prior studies have suggested associations between synesthesia and specific neurological profiles, including autism spectrum disorder and migraine.1,2 However, little is known about the prevalence and characteristics of synesthesia among patients with epilepsy.

METHODS

This pilot study3 aimed to investigate the occurrence of GCS in individuals with epilepsy and to explore the relationship between synesthetic experience and seizure type. The methodology was straightforward: 40 participants with epilepsy were surveyed regarding subjective GCS experiences.Those affirming these experiences underwent further assessment using a standardized synesthesia battery hosted on The Synesthesia Battery website, which evaluates both consistency (stability of color associations over time) and congruency (accuracy and speed of matching graphemes with colors).4

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

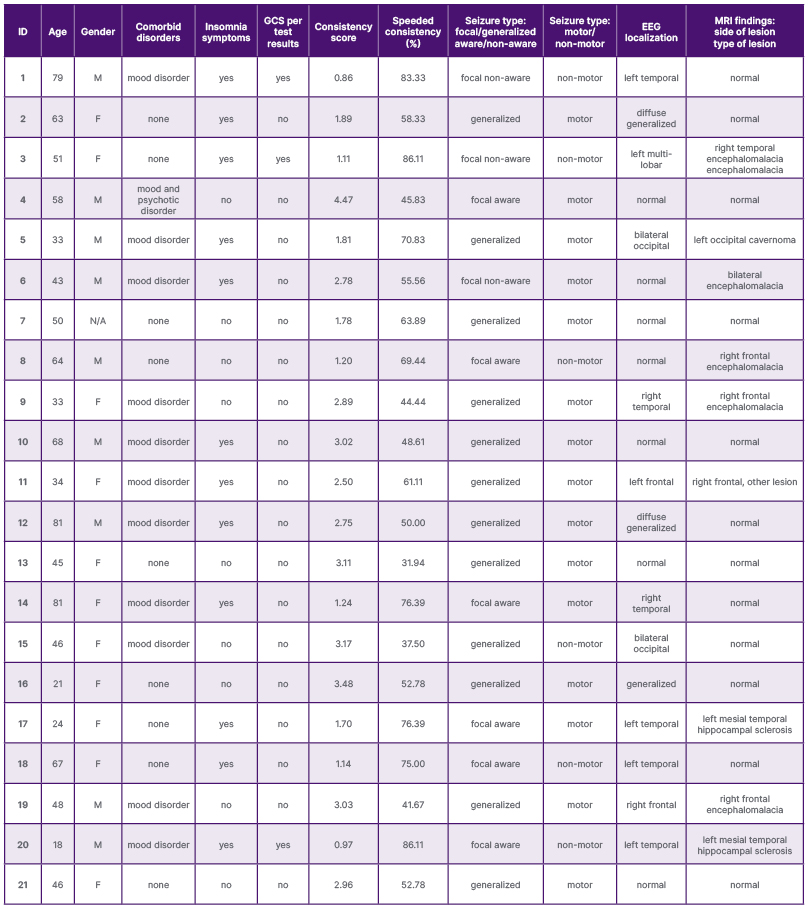

Out of 40 participants, 21 reported subjective GCS experiences, and three (7.5%) met objective criteria for synesthesia based on the battery (Table 1). This prevalence is notably higher than that reported in the general population, estimated between 0.05–4.4%.5,6 A key finding was that individuals with focal seizures exhibited significantly lower consistency scores (median 1.2) and higher congruency scores (76.4), indicating more accurate and quicker color-grapheme responses but less consistency in repeated associations. In contrast, those with generalized-onset seizures had higher consistency scores (2.9) and lower congruency scores (51.4), suggesting more stable associations but slower processing. These differences were statistically significant (p=0.006 for consistency and p=0.001 for congruency).

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics, synesthesia battery results of all tested participants.

EEG: electroencephalogram; GCS: grapheme-color synesthesia; F: female; M: male.

Moreover, participants with non-motor seizures had similar trends: lower consistency (1.1) and higher congruency (79.2) compared to patients with motor seizures (2.8 and 52.8, respectively), again with statistical significance (p=0.011 and p=0.036). These patterns suggest that certain seizure types may influence cross-modal sensory integration and perceptual processing.

The authors hypothesize that the heightened prevalence of GCS in this sample could reflect underlying neural hyperconnectivity or disinhibition in sensory regions, particularly within the temporo-parietal junction, known to be implicated in synesthesia.7,8 Focal seizures, especially those arising from temporal lobe structures, may amplify or uncover latent synesthetic networks by disrupting inhibitory gating mechanisms.8 Similarly, non-motor seizures might affect perception and sensory integration more subtly than motor seizures, thus predisposing to synesthetic traits.

This study adds to a growing body of literature that views synesthesia not merely as a curiosity, but as a window into atypical brain organization. Though limited by sample size and reliance on self-report for initial screening, the findings warrant larger-scale investigations. Future studies should incorporate neuroimaging to explore functional connectivity patterns in synesthetes with epilepsy and investigate whether antiepileptic medications modulate synesthetic experiences.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, GCS may occur more frequently in individuals with epilepsy, particularly those with focal or non-motor seizure types. The observed differences in synesthetic test performance point to potential neural correlates of sensory cross-activation in epilepsy, meriting further investigation.