Meeting Summary

During this symposium, leading international epileptologists discussed the key challenges and opportunities that currently exist within the evolving global landscape of epilepsy diagnosis and management. Experts reflected on the challenges that environmental factors pose to epilepsy management worldwide, and considered how personalised medicine, new therapeutic advances, and AI are helping to reshape epilepsy care. Practical insights were also provided into the delivery of specialised epilepsy care at different resource levels and care settings.

Introduction

The meeting began with a selection of videos from patients with epilepsy (PWE) from around the world. In these, PWE shared their lived experiences of the condition and highlighted important issues that are common across the epilepsy space, such as stigmatisation and marginalisation. These videos emphasised some of the disparities currently existing in global epilepsy care, while also highlighting recent positive developments, including advances in telemedicine fuelled by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Epilepsy and the Environment

Climate change has pervasive effects on health, explained Medine Gulcebi, Professor of Clinical Pharmacology at Marmara University School of Medicine, Istanbul, Türkiye. New global temperature records continue to be set, and approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year are predicted between 2030–2050, attributable to the indirect effects of climate change.1 A recent review paper examining the impact of adverse weather events on neurological disorders found a bimodal relationship between epilepsy and extreme temperatures.2 Unfortunately, a global disparity exists between regions most affected by climate change and the countries conducting most of the research, which are also major contributors to its causes.2 Low-income countries carry the highest burden of epilepsy, more than double that of high-income nations, plus they are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change.3 They also have the largest treatment gap for epilepsy, with limited availability and access to newer antiseizure medications (ASM), coupled with issues around medication quality and storage conditions.3 Therapeutic drug monitoring is not in widespread use, and the inappropriate transport of blood samples over long distances without a cold chain can result in misleading drug levels. The treatment gap in low-income countries is also accompanied by reduced adaptive capacity indicators required to counter climate-induced weather changes, such as malnutrition or loss of electricity.3

Gulcebi explained that people with epilepsy are vulnerable to adverse weather events due to several disease-related factors. The resulting negative consequences can include deterioration of seizure control (particularly in extreme temperatures), aggravation of comorbidities, and an increase in sudden unexplained death in epilepsy risk.4-6 Adverse weather has two main impacts: enhancing known seizure precipitants, such as sleep deprivation and stress, and increasing medication-related problems.7 Climate change can also affect the tropical causes of epilepsy, notably infections caused by vector-borne diseases.2 One example is the West Nile virus transmitted via the Culex mosquito, which, due to increases in global average temperatures, is now responsible for annual neuroinvasive disease outbreaks in Europe.8,9

Climate change can also cause medication-related problems due to the disruption of drug delivery or healthcare systems and the displacement of people.10,11 For example, during recent winter storms in the USA, around two-thirds of children with epilepsy experienced difficulties in obtaining their medications. This is important, Gulcebi stressed, because an adequate supply of and adherence to ASMs is key to seizure control and treatment success in epilepsy. In addition to access, storage and stability of ASMs are important considerations. Prolonged exposure to extreme temperatures or humidity (outside the recommended 15–25 oC storage range) can impair both the potency and bioavailability of ASMs. In particular, changes in pharmacokinetics may reduce clinical efficacy due to decreased blood levels. ASMs also have a narrow therapeutic window and are subject to potential drug–drug interactions and therapeutic resistance. Very recently, the melting of sodium valproate tablets has been reported in the Philippines for the first time, and similar case reports have also been reported for carbamazepine.3,7

Another key focus area for studying climate change effects in epilepsy is adverse events. Gulcebi referenced a recently published paper from her own group showing high rates of hyponatraemia-related hospitalisations linked to carbamazepine and its derivatives during the summer months in Southern Italy.12 Some ASMs, notably topiramate and zonisamide, can also predispose individuals to heatstroke through impaired thermoregulation and reduced sweating. Described risk factors include young age, high doses, poor hydration, and environmental/occupational exposure to heat.7 Finally, Gulcebi explained that there have also been case reports indicating a link between climatic factors and cutaneous adverse drug reactions induced by ASMs, particularly lamotrigine-induced photosensitivity and phenytoin-related rash.

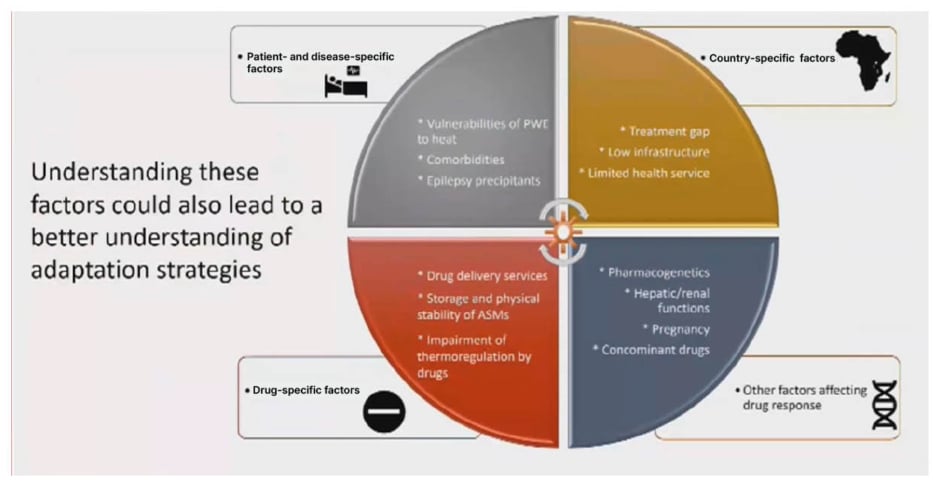

Ultimately, the relationship between extreme temperatures and seizure control is complex due to the numerous factors at play, Gulcebi concluded (Figure 1). However, as adverse weather events and temperature fluctuations become more frequent and severe, improved adaptation and mitigation strategies are needed. It is important to provide practical recommendations to people with epilepsy, including information about climate change effects, guidance on medication storage, and advice on maintaining a healthy diet, adequate fluid intake, and good quality sleep. Specific vulnerabilities to climate change effects need to be identified, and certain medications may need to be avoided or more closely monitored. There is also an urgent need for multidisciplinary research to delve deeper into this increasingly relevant topic and address key research priorities, including the impact of comorbidities and co-medications, as well as adverse events associated with disrupted thermoregulation.2,7,13,14

Figure 1: The relationship between extreme temperatures and seizure control.

ASM: antiseizure medication; PWE: patients with epilepsy.

Precision Medicine: The Changing Face of Epilepsy Diagnosis and Management Through Genetics

Rikke Moller, Professor at the Danish Epilepsy Centre in Filadelfia, Denmark, began her talk on precision medicine in epilepsy by defining the broader concept of precision health. This refers to the optimal treatment or prevention of disease states through targeted treatment of an underlying health condition, while considering the whole biological, psychological, and sociocultural context of the affected individual.15 Precision health encompasses two key components: precision diagnosis and precision management.15

Access to genetic testing is crucial for the precision diagnosis of a child with suspected genetic epilepsy, emphasised Moller. Currently, the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) recommends genetic testing in early-onset epilepsies, epilepsy with intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorder and/or other comorbidities, progressive myoclonus epilepsies, and non-lesional focal epilepsies in specific familial syndromes.16 Genetic diagnosis is important because it ends the diagnostic odyssey for patients and their families, Moller explained. It also informs a range of other factors, including clinical management, prognostication, and recurrence risk counselling, while opening up access to vital resources and support.16 In the international pilot study Gene-STEPs, use of rapid genome sequencing in a cohort of patients with early seizure onset (<12 months) was able to identify a genetic cause in 43% of cases, and this genetic diagnosis had immediate clinical utility.17

More than 900 genes have been identified as monogenic causes of epilepsy, and many different biological mechanisms have been implicated in the underlying pathophysiology, including ion channels, transporters, synaptic proteins, cell signalling and metabolism, and epigenetic regulation.18 As new treatments for epilepsy are developed, Moller highlighted two important principles that require close collaboration between laboratory and clinical researchers. Firstly, one gene does not always equal one disease, and both gain-of-function (GOF) and loss-of-function (LOF) variants can lead to a spectrum of different disorders.19 Secondly, phenotypic heterogeneity must be understood in order to predict patient outcomes and inform therapeutic decision-making.

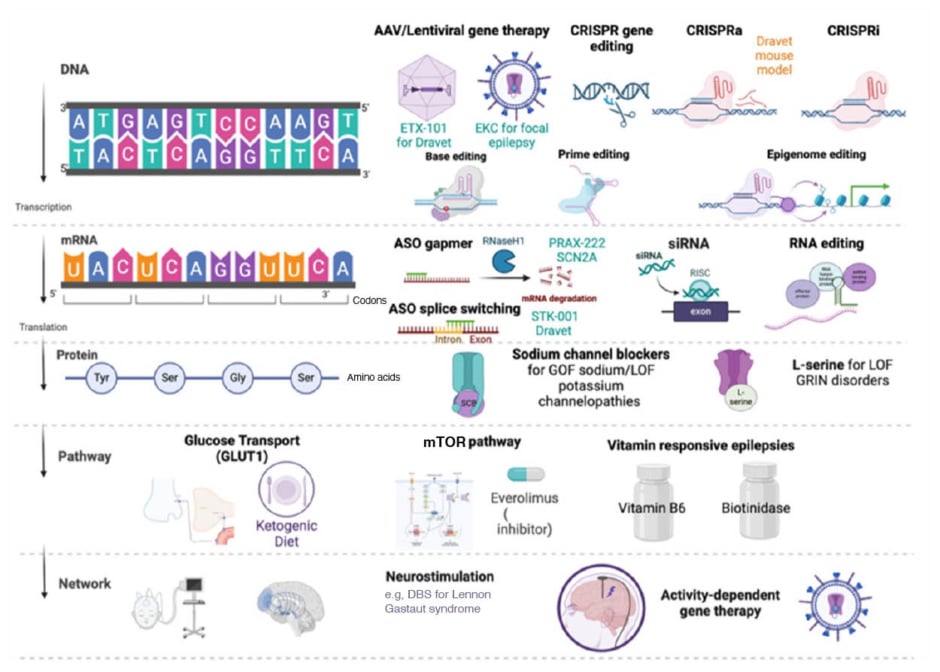

Moller reviewed some of the current and future opportunities for precision treatment in childhood epilepsy, targeting DNA, mRNA, and proteins, as well as underlying signalling pathways and neural networks (Figure 2).15 Understanding the phenotype-genotype correlation is key to advancing these precision therapies and maximising their clinical utility, Moller explained, as exemplified by decision trees for patients with identified SCN1A and SCN2A mutations. Patients within the genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus/Dravet spectrum with a GOF mutation in SCN1A can receive precision therapy with sodium channel blockers, whereas this treatment approach should be avoided in those with LOF variants.15 Similarly, in SCN2A-related disorders, neonatal seizure onset before 3 months indicates a GOF amenable to sodium channel blockers, while onset at >3 months of age suggests a LOF variant.20

Figure 2: Current and future opportunities for precision treatment in childhood epilepsy.15

AAV: adeno-associated virus; ASO: antisense oligonucleotides; CRISPR: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; CRISPRa: CRISPR activation; CRISPRi: CRISPR interference; DBS: deep brain stimulation; EKC: Engineered Potassium Channel; GLUT1: glucose transporter Type 1 protein; Gly: glycine; GOF: gain-of-function; GRIN: Glutamate Receptor, Ionotropic, N-Methyl D-Aspartate; LOF: loss-of-function; RISC: RNA-induced silencing complex; Ser: serine; siRNA: small interfering RNA; Tyr: tyrosine.

Several new precision medicine approaches for epilepsy have shown success in recently published clinical trials. In open-label extension studies, the antisense oligonucleotide zorevunersen plus standard of care led to reductions in convulsive seizure frequency, coupled with improvements in cognition and behaviour, in patients with Dravet syndrome that were maintained through 3 years of treatment.21 These results suggest that zorevunersen may not only be an effective ASM, but also a disease-modifying therapy, noted Moller. Another investigational antisense oligonucleotide, elsunersen, led to a 60% reduction in seizure frequency in a recently published proof-of-concept study in a preterm infant, with early-onset developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE).22 The EMBRAVE trial of elsunersen in early-onset SCN2A DEE is currently ongoing, and initial results from four treated patients indicate a positive effect on both seizure frequency (43% reduction) and seizure-free days (48% increase).23 Relutrigine (PRAX-562) is a first-in-class, small-molecule, differentiated sodium channel modulator with superior selectivity for disease-state sodium channel hyperexcitability, which is currently undergoing clinical development in DEE. Results from Cohort 1 of the EMBOLD study of relutrigine showed short- and long-term improvements in motor seizure frequency, alongside marked seizure freedom; enrolment into the EMBOLD Cohort 2 and the EMERALD registrational studies is continuing.24 Moller described drug repurposing as another “hot topic in the epilepsy field,” although the supporting evidence stems mainly from case reports rather than RCTs.25 Nevertheless, she advocated this as an approach worth considering for patients with intractable genetic epilepsies.

Despite the many advances, Moller acknowledged that multiple barriers exist to accelerating the development and translation of promising novel therapies and getting “precision medicine to more patients.”26 Genetic diagnosis is a key precursor to the implementation of precision medicine, yet access to genetic testing and novel therapeutics remains unequal across the globe. Both GOF and LOF phenotypes can occur, and different disease subgroups require different molecularly targeted treatments. Moller stressed that multidisciplinary collaboration is also crucial to understand underlying pathological mechanisms and phenotypes, delineate disease natural history, and establish optimal care pathways.26

Monogenic epilepsies are key targets for precision medicine, and this marks “a very exciting time with lots of promising therapies on the horizon,” Moller concluded. Ultimately, the aim is to improve care for people with rare epilepsies and reduce inequalities in access to the best diagnostic tools, treatment practices, and investigational drugs.26

The Role of AI in the Diagnosis and Management of Epilepsy

Arjune Sen, Professor of Global Epilepsy at the University of Oxford, UK, began by outlining the ultimate vision for the use of AI in epilepsy. The hope is that better data management facilitates quicker and more accurate diagnosis, leading to shortened hospital stays and cost savings that in turn fuel research and therapeutic advances that translate into improved outcomes for patients. However, epilepsy is a clinical diagnosis, and description of seizures is very nuanced, with marked differences across regions and cultures, plus stigmatisation remains profound. The use of AI in diagnosis would therefore require the accurate capture, transcription, and summary of patients’ voices in their own words, which would generate huge volumes of data, Sen explained. It would also require training and the use of large language models that are themselves subject to bias.

Sen described a recent study to develop and validate a diagnostic aid for convulsive epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa.27 This process involved the creation of a large data training set for modelling, which was then tested against both internal and external data validation sets. The result was eight key questions that could be utilised to identify convulsive epilepsy. In logistic regression modelling, the area under the curve, a recognised marker for success in AI, was 0.92 and 0.96 for the internal and external datasets, respectively.27 Performance sensitivity was 85.0%, and specificity was 93.7%.27 However, next step analysis revealed that model weights and optimal thresholds varied markedly across the different study sites.28 In general, internal performance decreases when the model is trained using data from multiple sites, while external performance is better, so it’s about finding an optimal balance, Sen elaborated.

The key diagnostic questions identified through AI modelling were subsequently developed into a mobile app intended to streamline epilepsy screening in clinical practice. Approximately 5,000 clinical screenings with the Epilepsy Diagnostic Companion (EDC) have already been completed in Ghana and Kenya, and other sites have begun the onboarding process. This quick and intuitive mobile app has been designed with resource-limited settings in mind, allowing users to choose their preferred local language.

AI tools can also augment existing diagnostic tests for epilepsy. Sen described EEG as an ideal modality for the application of AI because its waveform lends itself to mathematical modelling. In a recent study, the SCORE-AI tool (Holberg EEG, now acquired by Natus [Middleton, Wisconsin, USA]) achieved human expert-level performance in a fully automated interpretation of routine EEGs.29 AI can also be applied to MRI scans to optimise the identification of lesions and pinpoint those suitable for potential neurosurgical intervention.30,31 In genomics, AI may have a future role in streamlining bioinformatics pipelines, given the large volumes of data involved.32 However, Sen acknowledged that potential future applications of AI in epilepsy treatment and care are more complex. Evidence from other therapy areas suggests a potential role for AI in synthesising complex datasets for network meta-analysis to optimise treatment selection.33

Overall, there is a clear need for big data in epilepsy, Sen emphasised, because this is a common and treatable condition, but it lacks sufficient clinicians to meet existing needs. Epilepsy also disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, often in resource-limited or hard-to-reach communities. However, in addition to the multiple challenges related to AI itself, Sen cautioned that there are also specific risks to consider related to the use of big data in epilepsy management.34 Due to the black-box nature of AI algorithms, good data in does not necessarily equate to good data out. Epilepsy is already a marginalised and stigmatised condition, so it is important that the datasets used for AI modelling reflect the target patient population, Sen stressed. Otherwise, biases may exacerbate the risk of marginalisation. Big data therefore needs small data, he explained, which reflect the patients’ own lived experience in order to be embedded effectively in healthcare.35 Evidence from the broader application of AI in healthcare underscores the importance of considering applicability across diverse patient populations, including different races, ancestries, and genders.36

In summary, AI offers unparalleled opportunities in epilepsy, coupled with unparalleled risks. Equitable and transparent partnerships are crucial to ensure that already marginalised patients do not become even more so. Big data and AI technology applications need to be grounded in patient needs and deliverable by clinical teams working together. Ultimately, it is unlikely that AI will replace epileptologists, Sen concluded, but clinicians who utilise AI sensibly may replace those who do not.

Specialised Epilepsy Care at Different Settings and Resource Levels

Patricia Braga, Associate Professor at the University of the Republic (UdelaR) in Montevideo, Uruguay, explained that specialised care refers to health services focusing on specific medical conditions and/or groups of patients, with the aim of improving outcomes compared to the standard of care. Specialised care is a key component of a comprehensive healthcare system and should not be viewed in isolation. In epilepsy specifically, it implies providing multidisciplinary care that encompasses all stages of disease management, from causes to consequences. This includes diagnostics, treatments, integrated care for comorbidities, transitions of care across life and disease stages, and structured educational support. All healthcare services, Braga noted, have the scope to offer some level of specialised epilepsy care, even primary care providers if they have received enhanced epilepsy training. Depending on the level of service, different resources and tools are needed to provide optimised patient care. For example, Level 4 epilepsy centres (EC) will require more advanced technologies and specialised clinicians.

Braga went on to outline some practical suggestions and requirements for setting up specialised epilepsy care services in both high and low-resource settings. Most of the existing guidelines are from the National Association of Epilepsy Centers (NAEC) and relate to requirements for setting up specialist Level 3 and 4 ECs.37 Braga explained how these guidelines have evolved over time, culminating in the most recent guidance published in 2024. This includes 52 recommendations covering four key domains: inpatient services and epilepsy monitoring unit, diagnostic methods, surgery, and comprehensive outpatient services.37 The NAEC advocates for comprehensive ECs equipped to provide both routine and highly specialised care for PWE, and recommends a patient-centred approach that encompasses comorbidities, psychosocial aspects, and education, in addition to pharmacological treatment.37 But is this an ideal model for epilepsy care, asked Braga. A recent nationwide survey conducted across clinics, hospitals, and epilepsy centres in Japan found that, while ECs were highly proficient in delivering surgical interventions, they fell short in providing integrated and holistic patient care.38 The issue of downward referral and patient stagnation in ECs was also highlighted.38

In low-resource settings, Braga explained that there are certain “must-haves” for setting up an epilepsy care service. At Level 1 (primary care), home videos and access to CT scans are essential diagnostic tools, while at least one ASM is required for treatment, giving priority to broad-spectrum drugs with favourable pharmacokinetic properties and high efficacy. An integrated approach to comorbidities and psychosocial aspects is also important. Level 2 (neurologist) care requires access to EEG and MRI (with CT as an alternative) for diagnosis. Different ASM options are needed if the first-line agent was not tolerated/ineffective, together with ASM monitoring. At both Level 1 and 2, referral to a higher tier of care or other relevant specialities (e.g., mental health support) should be available. Essentials for a Level 3 EC without surgery will include epileptologists, plus video EEG and high-quality (1.5 T) MRI for diagnosis. For Level 4 surgical care, requirements are similar, but with the capacity to provide long-term monitoring and neuroimaging. Although epilepsy surgery is currently positioned as the last therapeutic resort, evidence suggests that it can be cost-effective and that efforts should be made to improve access to surgical treatment for patients with drug-refractory epilepsy.39 Across all care levels, Braga stressed that “the real must-haves are the trained human resources.” When establishing an epilepsy care service in a low- or middle-income country, it is essential to understand the community and the healthcare system and define priorities according to patient needs. Braga advised starting with small steps to assess feasibility, including team recruitment and training, and to seek institutional support where possible.

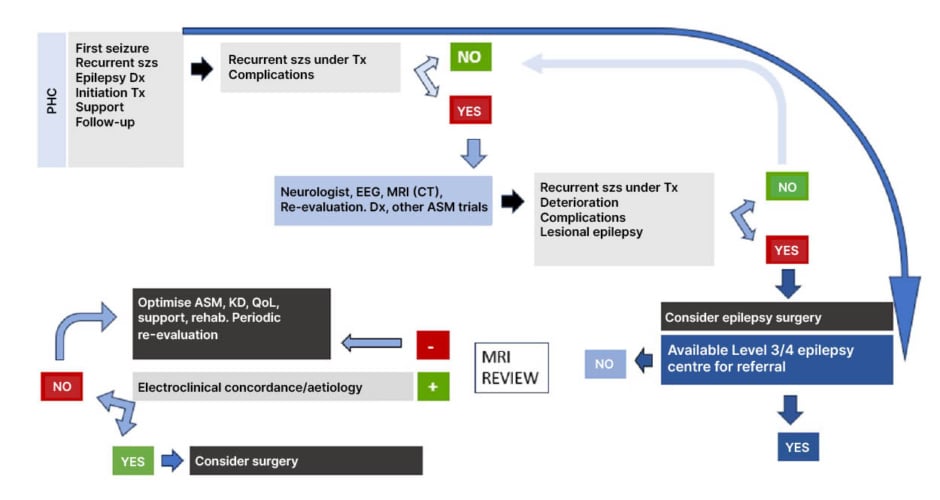

In summary, Braga reiterated that any healthcare service has the capability to deliver some level of specialised epilepsy care. By providing improved diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, or support to PWE, this service can then become a critical node in the overall care network. Overall, there are two main models of epilepsy care that can be adopted: one centred around early referral to highly specialised ECs and a second, stepwise approach, which may be more feasible in lower-income settings (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The two main models of epilepsy care.

Figure courtesy of Patricia Braga.

ASM: antiseizure medication; Dx: diagnosis; KD: ketogenic diet; PHC: primary healthcare; QoL: quality of life; szs: seizures; Tx: treatment.