Update: [February 4, 2026] Figure 4 has been updated for accuracy. The figure title was amended and the associated reference updated accordingly.

Interview Summary

Ozanimod is a sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator indicated for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (RMS), including clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease, in adults. Contraindications for ozanimod include patients who, in the last 6 months, experienced myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke, transient ischemic attack, decompensated heart failure requiring hospitalization, or Class III/IV heart failure, or have a presence of Mobitz Type II second-degree or third-degree atrioventricular block, sick sinus syndrome, or sino-atrial block, unless the patient has a functioning pacemaker; patients with severe untreated sleep apnea; or patients taking a monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitor. The molecular structure of ozanimod is distinct from that of earlier S1P receptor modulators, such as fingolimod, and binds with high affinity to S1P1 and S1P5. Experts Regina Berkovich, Founder and Director of the Berkovich MS Center and Research Institute and nationally recognized multiple sclerosis (MS) specialist based in West Hollywood, California, USA; and Robert Shin, Professor of Neurology and Ophthalmology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and Director of the UVA Multiple Sclerosis and Clinical Neuroimmunology Center, USA, discussed several aspects of ozanimod therapy. They discussed ozanimod’s molecular structure, which distinguishes it from earlier S1P modulators, and reviewed long-term safety data (up to 7 years) from the DAYBREAK open-label extension (OLE) study and real-world evidence (RWE), including rates of serious adverse events (AE), infections, and treatment discontinuations. Finally, they described ozanimod’s efficacy in reducing annualized relapse rates (ARR) and MRI lesion activity in patients with early relapsing MS, and data on 3- and 6-month confirmed disability progression (CDP). Shin and Berkovich note how, taken together, these findings show that ozanimod as an oral disease-modifying therapy (DMT) may be suitable for early intervention in adults with relapsing MS.AN UNMET NEED FOR PATIENTS WITH RELAPSING MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

MS is a chronic, immune-mediated, central nervous system disorder.1 It involves persistent, low-grade neuroinflammation and recurrent relapses of demyelinating lesions with heterogeneous clinical presentation.1 Relapses in early disease stages are typically followed by partial or full recovery, termed remission.1 MS is more prevalent in females, and the relapsing-remitting form represents the most common early phenotype, seen in over 90% of cases.1 As patients transition to the secondary progressive phase, disability gradually accumulates, with or without continuing relapses.1 This disease course underscores the need for early and effective intervention.1

Current therapeutic approaches target three key goals: reducing inflammation, preventing relapses, and delaying progression to secondary progressive MS. DMTs, delivered orally, by injection, or via infusion, suppress or modulate immune activity to achieve these goals.1 However, Shin highlighted that there is an unmet need for oral DMTs that people with early MS can remain on long-term without interruption by AEs. Despite clear evidence that early treatment improves outcomes, around 20% of patients do not initiate DMT within 6 months of diagnosis.2-4 High-efficacy immunosuppressive therapies, such as anti-cluster of differentiation (CD)20 agents, demand close monitoring and carry risks associated with sustained B cell depletion and increased susceptibility to infections.5-7 Accordingly, there remains a need for therapies that combine efficacy with a long-term safety profile.

NOT ALL SPHINGOSINE 1-PHOSPHATE RECEPTOR MODULATORS ARE THE SAME

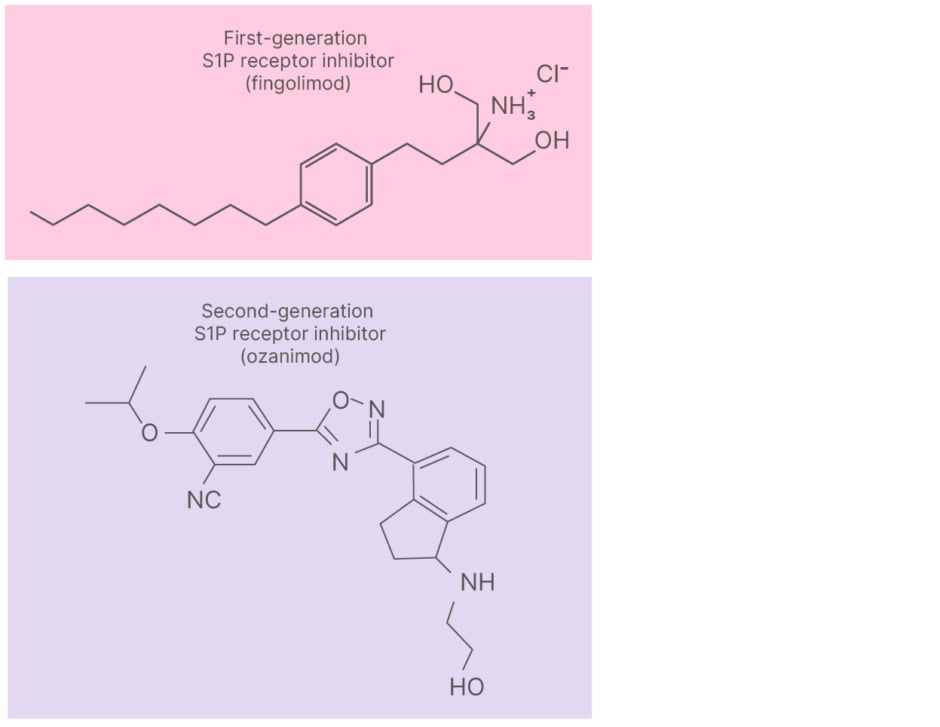

S1P receptor modulators are a class of oral immunomodulatory DMTs approved for RMS (Figure 1).1 Fingolimod is a first-generation oral S1P receptor modulator approved for children 10 years or older and adults with relapsing-remitting MS.1 Fingolimod is a pan-S1P receptor modulator and has been associated with side effects that stem from its receptor promiscuity.10-13 Shin noted: “We started out with a fairly non-selective S1P agent, but the subsequent generations are more selective in terms of the subtypes of S1P receptor they target.” Second-generation S1P modulators, including ozanimod, were developed to refine pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and receptor selectivity.1,10,12 Shin highlighted that ozanimod, a small lipophilic molecule (Figure 1), was specifically designed with improved receptor subtype selectivity.1,10,12

Figure 1: Molecular structure of fingolimod and ozanimod.8,9

CNS: central nervous system; S1P: sphingosine 1-phosphate.

Although the exact mechanism by which ozanimod exerts its therapeutic effects in MS remains unknown, Berkovich noted the evidence that ozanimod binds with high affinity to S1P1 and S1P5 receptors.14 S1P1 modulation by ozanimod blocks lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes, lowering peripheral blood lymphocytes.14 However, she noted that “it is not a true lymphopenia as it normalizes within a predictable timeframe,” noting that this intended pharmacodynamic effect reverses within approximately 30 days of treatment cessation, with around 80–90% of patients returning to normal lymphocyte levels within 3 months.10,14

Preclinical evidence also suggests that ozanimod crosses the blood–brain barrier and may have direct effects in the central nervous system by acting on S1P receptors on oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, microglia, and neurons.10-12,15-17

PIVOTAL TRIALS: OZANIMOD SAFETY PROFILE COMPARED WITH INTERFERON β-1a

The safety and efficacy of ozanimod were confirmed in two Phase III clinical trials. SUNBEAM14,18,19 (NCT02294058; 1 year; N=1,346) and RADIANCE14,20,21 (NCT02047734; 2 years; N=1,313) were multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, active treatment-controlled studies of daily oral ozanimod 0.46 mg (not approved for maintenance dose) or 0.92 mg oral daily dose versus a weekly interferon β-1a (IFN β-1a) 30 µg intramuscular injection. The primary endpoint for both studies was ARR. Additional outcome measures included the number of new or enlarging MRI T2 lesions over 12 and 24 months; the number of MRI T1 gadolinium-enhancing (GdE) lesions at 12 and 24 months; and the time to CDP after 3 months and 6 months.14

In both trials, patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive either ozanimod or IFN β-1a for at least 12 months (SUNBEAM) or 24 months (RADIANCE).19,21

In SUNBEAM (n=1,346) and RADIANCE (n=1,313), ozanimod achieved a safety profile comparable to IFN β-1a, with similar rates of infection (35% versus 34%), herpes zoster infections (0.6% versus 0.2%), serious infections (1.0% versus 0.8%),14 and AEs leading to discontinuation for patients treated with 0.92 mg (2.9–3.0% versus 3.6–4.1%).19,21 The most common AEs (with an incidence of at least 2% in ozanimod-treated patients and at least 1% greater than IFN β-1a) were upper respiratory infection (26% versus 23%), hepatic transaminase elevation (10% versus 5%), orthostatic hypotension (4% versus 3%), urinary tract infection (4% versus 3%), back pain (4% versus 3%), hypertension (4% versus 2%), and upper abdominal pain (2% versus 1%).14

A DEEP DIVE INTO THE LONG-TERM SAFETY PROFILE OF OZANIMOD

Shin emphasized that, while ozanimod showed comparable safety and superior efficacy in comparison to IFN β-1a in the pivotal trials,19,21 long-term evaluation remains essential. Both he and Berkovich underscored the importance of patients remaining on effective, well-tolerated DMTs for extended time periods without switching. The DAYBREAK OLE (NCT02576717) evaluated long-term use of ozanimod.22 This single-arm, open-label, Phase III study enrolled patients who completed SUNBEAM or RADIANCE to assess ozanimod’s long-term safety and efficacy. As Shin explained, the objective of an OLE study is “to [determine whether] the safety profile remains good … and efficacy persists over time.” In DAYBREAK, all participants who entered from the preceding Phase III trials underwent dose escalation to ozanimod 0.92 mg once daily, regardless of their previous treatment assignment, and maintained this dose throughout the study.22

Overall Adverse Events

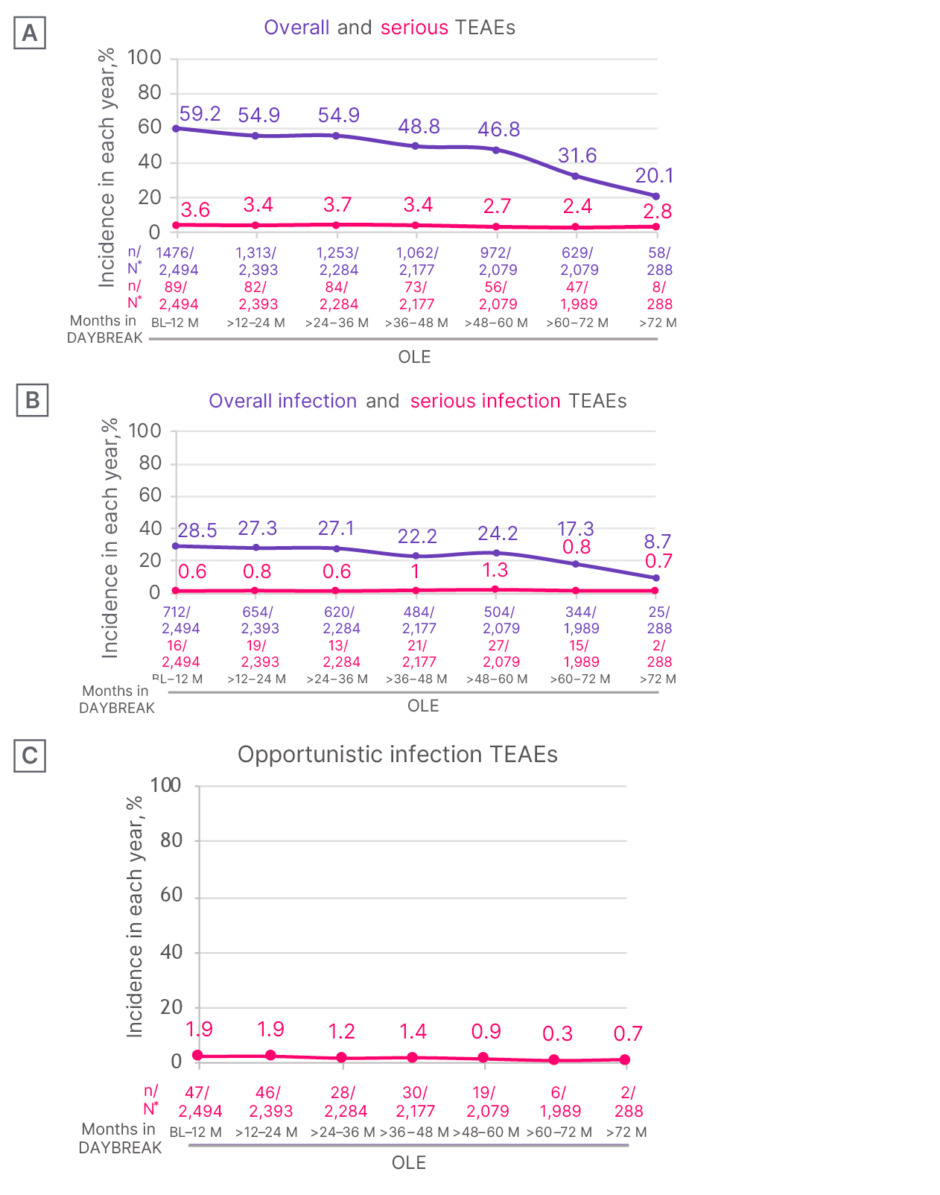

In the DAYBREAK OLE (n=2,256), 89.0% (n=2,219) of patients reported treatment-emergent AEs (TEAE) (Figure 2A). Of these, 15.3% (n=381) were serious TEAEs; 9.6% (n=240) were severe TEAEs; and 3.9% (n=98) were TEAEs leading to permanent treatment discontinuation.22 TEAEs greater than or equal to 10% were nasopharyngitis (21.3%), headache (17.1%), and COVID-19 (16.5%).22 Similar safety patterns were seen in the continuous ozanimod 0.92 mg oral daily dose (n=881) population.22

Treatment-Emergent Infections

Over up to 72 months’ follow-up, treatment-emergent infections generally remained stable or declined over time (Figure 2B), and serious and opportunistic infections remained < 2%; one case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy occurred (Figure 2C).22 Ozanimod may increase the susceptibility to infections, some serious in nature. Life-threatening and rare fatal infections have occurred in patients receiving ozanimod. Consider interruption of treatment with ozanimod if a patient develops a serious infection.14

Figure 2: Safety patterns over time with ozanimod during the DAYBREAK open-label extension trial in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis.22

*Number of participants who had an event in the time interval, divided by the number of participants who were ongoing or discontinued treatment at the same interval; a participant could be counted under multiple time intervals based on the TEAE, TEAE start date, and treatment duration, but if a participant had multiple occurrences of a TEAE in one interval, they were counted once.

Incidence in each year (%) of A) overall and serious TEAEs; and B) overall infection and serious infection TEAEs; C) opportunistic infection TEAEs.

Figure reproduced with permission from Mult Scler.22

M: months; OLE: open-label extension; TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event.

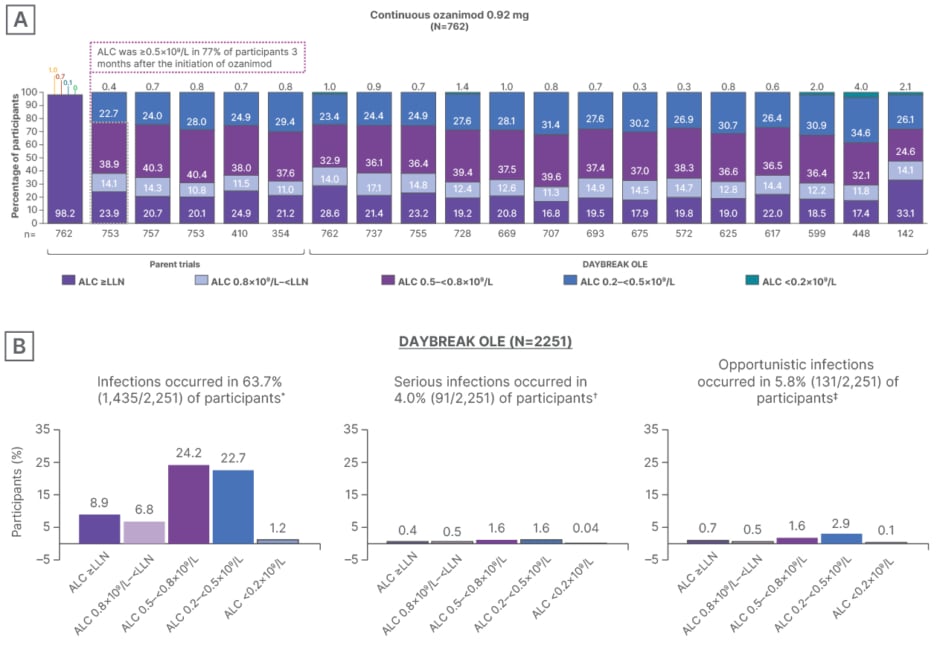

Absolute Lymphocyte Count and Infection

Absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) was ≥0.5×109 /L in 77% of participants 3 months after the initiation of ozanimod, and remained stable throughout 72 months of follow-up (Figure 3A).23 Patients experienced a mean peripheral blood lymphocyte reduction of approximately 45%. Median time to recovery to normal lymphocyte range was 30 days after ozanimod discontinuation, with 90% of patients with RMS recovering to normal within 3 months.14 Berkovich reiterated that the lymphopenia seen when taking S1P agents “is really artifactual,” referencing the redistribution of lymphocytes from the blood to the lymph nodes.14 In the DAYBREAK OLE study, participants who experienced an initial infection were categorized based on ALC values either at the lab visit prior to the time of first infection or just after the time of first infection. Most patients with any infection had an ALC of between 0.2×109 /L and 0.8×109 /L at the time of first infection, and few patients had an ALC <0.2×109 /L at the time of first infection (Figure 3).24

Figure 3: Absolute lymphocyte count and infection risk with ozanimod during DAYBREAK open-label extension trial in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis.23

*Twenty-two participants had an infection with an ALC assessment performed outside of the ±92-day window and were not included in this analysis.

✝Six participants had an infection with an ALC assessment performed outside of the ±92-day window and were not included in this analysis.

‡One participant had an infection with an ALC assessment performed outside of the ±92-day window and was not included in this analysis.

A) ALC with continuous ozanimod from pivotal trials and DAYBREAK OLE. B) Percentage of participants with infections in DAYBREAK OLE (safety population). Participants who experienced an initial infection were categorized based on ALC values either at the lab visit prior to the time of first infection or just after the time of first infection. The minimum ALC is selected if ALC is available both prior to and after the first infection.

Figure reproduced with permission from Selmaj et al.23

ALC: absolute lymphocyte count; LLN: lower limit of normal; OLE: open-label extension.

Treatment-Emergent Malignancies

With up to 7 years’ follow-up, treatment-emergent malignancies among ozanimod-treated patients with MS were 324.8 per 100,000 person-years.22 According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database for 2021, the frequency of “cancer of any site” among the general US population was 446 per 100,000 person-years.25 Malignancies, such as melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, breast cancer, seminoma, cervical carcinoma, and adenocarcinomas, including rectal adenocarcinoma, were reported with ozanimod in controlled trials.14 In DAYBREAK, the incidence of malignant melanoma, non-melanoma cutaneous malignancies, and non-cutaneous malignancies was 6.3, 107.1, and 194.8 per 100,000 person years, respectively.26

Pregnancy

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Based on animal studies, ozanimod may cause fetal harm.14 Women of childbearing potential should use effective contraception during treatment and for 3 months after stopping ozanimod.14 In SUNBEAM and RADIANCE Phase III trials, patients were required to discontinue ozanimod if pregnancy was confirmed, unless they elected to terminate the pregnancy, in which case they were permitted to continue ozanimod. Male patients were to notify the investigator if their female partner became pregnant.14,19,21 In a total of 82 pregnancies, of which 57 were in patients with relapsing MS, all patients discontinued ozanimod in the first trimester. There were 44 (53%) live births, 39 (88.6%) of which were normal infants and four (9.1%) of which were premature births (11% for the general population).27 There has been no increased incidence of fetal abnormalities or adverse pregnancy outcomes.27 Rates of 12 spontaneous abortions (14.5%) and one duplex kidney (2.3%) were consistent with the general population (18–31% and 1.8%, respectively).27 Readers are directed to the important safety information at the end of this article for further information on fetal risk. For additional safety information, please see the full Prescribing Information and Medication Guide linked at the top of this article.

Rebound

Berkovich discussed the issue of rebound,1 which she described as the return of MS activity and/or severe exacerbation of disease or severe persistent increase in disability after treatment discontinuation. Rebound is a key concern for clinicians and patients, particularly when symptoms are “above and beyond just the return of MS activity,” as has been reported with fingolimod.1 Shin noted that, with ozanimod, “what is not seen is the kind of rebound …that we had seen with some other agents.” Findings from the DAYBREAK OLE study support this observation, where no patients experienced disease rebound, and only 3.3% (n=55/1,679) of patients experienced relapse after ozanimod discontinuation.28 Most relapses (98%; n=54/55) were mild or moderate, 2% (n=1/55) occurred while the patient was using a DMT, and 76% of patients made a full recovery.28

Real-World Evidence

In the DAYBREAK OLE study, ozanimod demonstrated a low discontinuation rate of 3.9% due to AEs across a follow-up period of up to 7 years.22 Real-world experience reinforces these findings. Shin noted that the tolerability profile of ozanimod allows his patients to remain on the therapy for extended periods. “In fact,” Shin remarked, “I think that that says a lot.”

RWE studies differ from randomized clinical trials in that they are observational in nature, use data from non-randomized patients in routine clinical practice, and only evaluate association and not causality. A retrospective RWE study (n=206) collected data from patients with MS who received ozanimod with up to 2 years of follow-up. This study found that by 2 years, 56 patients discontinued ozanimod with a discontinuation-free probability of 73%. Rates of pneumonia, urinary tract infection, worsening hypertension, headache, and upper respiratory tract infection were 0%, 2.7%, 2.7%, 3.6%, and 3.6% at 6 months (n=112); 0%, 0%, 4.1%, 4.1%, and 7.2% at 18 months (n=97); and 1.5%, 1.5%, 3.0%, 9.0%, and 7.5% at 24 months (n=67), respectively.29

SPOTLIGHT ON EFFICACY: LONG-TERM DATA SHOW THAT OZANIMOD MAINTAINS LOW ANNUALIZED RELAPSE RATE AND LOW MRI LESION ACTIVITY

Ozanimod significantly improved ARR over 1–2 years (0.181 in SUNBEAM; 0.172 in RADIANCE) compared with IFN β-1a in Phase III trials (relative reduction: 38–48%; p<0.0001).14 Long -term follow-up showed that patients treated with ozanimod for up to 7 years had an ARR of 0.098 and 69.1% of participants, respectively, remained relapse-free.22

Ozanimod also demonstrated superior reduction in GdE lesions (relative reduction: 53–63%; p≤0.0006) and new or enlarging T2 lesions (relative reduction: 42–48%; p<0.0001) compared with IFN β-1a in Phase III trials.14 Long-term follow-up showed that, among patients treated with continuous ozanimod for 5 years, the adjusted mean number of GdE lesions and new or enlarging T2 lesions per MRI scan was 0.07 and 0.87, respectively.22 As Berkovich emphasized: “We trust and verify. But with that verification, it is rewarding, nevertheless, to find out that our clinical impression gets supported by the MRI data and by the long-term disability status observation.”

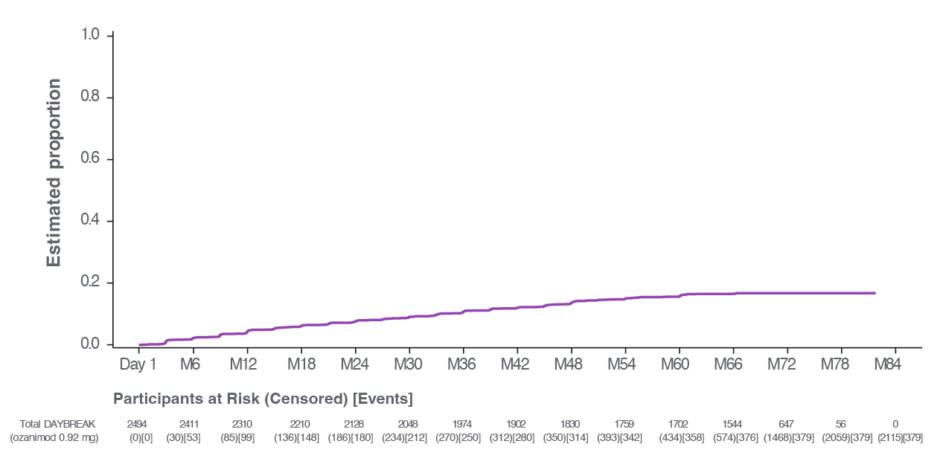

In the pivotal Phase III trials, 92.4% of patients showed no 3-month CDP with ozanimod, and statistical significance was not reached for CDP with ozanimod; however, 7.6% of patients on ozanimod experienced 3-month CDP, similar to IFN β-1a (7.8%).19,26 With up to 7 years’ follow-up in the DAYBREAK OLE, 82.8% (n=2,066/2,494) and 84.8% (n=2,215/2,494) of patients showed no 3- and 6-month CDP with ozanimod, respectively (Figure 4).22 Berkovich explained: “There was no significant difference in disability accumulation, because very few people accumulated disability in those pivotal studies.” Berkovich also noted that “Ozanimod showed superiority [in ARR and MRI lesion activity],17 which translated into the long-term observations that Dr Shin spoke about, and we both observe in our clinical practices.”

Figure 4: Time to onset of 6-month confirmed disability progression with ozanimod during DAYBREAK open-label extension trial in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis.22

Figure reproduced with permission from Selmaj et al.22

OLE: open-label extension.

CONCLUSION

Ozanimod is an S1P receptor modulator that is structurally distinct from the first-generation treatment, fingolimod, and binds with high affinity to S1P1 and S1P5.1,10,14 As Berkovich noted, the “pharmacological representatives of the same class are not the same,” distinguishing ozanimod’s structural distinction within the S1P modulator class.

Ozanimod has demonstrated comparable safety to platform therapy IFN β-1a.14,19,21 Long-term data showed that 15.3% of patients reported serious infections, 9.6% reported severe infections, and 3.9% of patients discontinued due to TEAEs.22 Furthermore, treatment-emergent malignancies occurred in 324.8 per 100,000 person years.22,24 Its once-daily administration, coupled with a demonstrated safety and efficacy profile, show that ozanimod may be an appropriate oral DMT for early treatment of patients with RMS. Berkovich added a patient-centered perspective: “When a patient leaves your office, they should feel better as compared to how they came…that is what realistically we can see with adequately treated patients.”

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

INDICATION

ZEPOSIA® (ozanimod) is indicated for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), to include clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease, in adults.

Contraindications:

- Patients who in the last 6 months, experienced myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), decompensated heart failure requiring hospitalization, or Class III/IV heart failure or have a presence of Mobitz type II second-degree or third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, sick sinus syndrome, or sino-atrial block, unless the patient has a functioning pacemaker

- Patients with severe untreated sleep apnea

- Patients taking a monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitor

Infections: ZEPOSIA may increase the susceptibility to infections. Life-threatening and rare fatal infections have occurred in patients receiving ZEPOSIA. Obtain a recent (i.e., within 6 months or after discontinuation of prior MS therapy) complete blood count (CBC) including lymphocyte count before initiation of ZEPOSIA. Delay initiation of ZEPOSIA in patients with an active infection until the infection is resolved. Consider interruption of treatment with ZEPOSIA if a patient develops a serious infection. Continue monitoring for infections up to 3 months after discontinuing ZEPOSIA.

- Herpes zoster and herpes simplex were seen in clinical trials of ZEPOSIA. Herpes simplex encephalitis and varicella zoster meningitis have been reported with sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulators. Patients without a healthcare professional-confirmed history of varicella (chickenpox), or without documentation of a full course of vaccination against varicella zoster virus (VZV), should be tested for antibodies to VZV before initiating ZEPOSIA.

- Cases of fatal cryptococcal meningitis (CM) and disseminated cryptococcal infections have been reported with S1P receptor modulators. If CM is suspected, ZEPOSIA should be suspended until cryptococcal infection has been excluded. If CM is diagnosed, appropriate treatment should be initiated.

- In clinical studies, patients who received ZEPOSIA were not to receive concomitant treatment with antineoplastic, non-corticosteroid immunosuppressive, or immune-modulating therapies used for treatment of MS. Concomitant use of ZEPOSIA with any of these therapies would be expected to increase the risk of immunosuppression. When switching to ZEPOSIA from immunosuppressive medications, consider the duration of their effects and their mode of action to avoid unintended additive immunosuppressive effects.

- Use of live attenuated vaccines should be avoided during and for 3 months after treatment with ZEPOSIA. If live attenuated vaccine immunizations are required, administer at least 1 month prior to initiation of ZEPOSIA.

Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML): PML is an opportunistic viral infection of the brain that typically occurs in patients who are immunocompromised, and that usually leads to death or severe disability.

PML has been reported in patients treated with S1P receptor modulators, including ZEPOSIA, and other MS therapies and has been associated with some risk factors (e.g., immunocompromised patients, polytherapy with immunosuppressants, duration of use). Based on data from patients with MS, longer treatment duration increases the risk of PML in patients treated with S1P receptor modulators, and the majority of PML cases have occurred in patients treated with S1P receptor modulators for at least 18 months. If PML is suspected, withhold ZEPOSIA and perform an appropriate diagnostic evaluation. If confirmed, treatment with ZEPOSIA should be discontinued.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) has been reported in MS patients treated with S1P receptor modulators who developed PML and subsequently discontinued treatment. IRIS presents as a clinical decline in the patient’s condition that may be rapid, can lead to serious neurological complications or death, and is often associated with characteristic changes on MRI. The time to onset of IRIS in patients with PML was generally within a few months after S1P receptor modulator discontinuation. Monitoring for development of IRIS and appropriate treatment of the associated inflammation should be undertaken.

Bradyarrhythmia and Atrioventricular Conduction Delays: Since initiation of ZEPOSIA may result in a transient decrease in heart rate and atrioventricular conduction delays, dose titration is recommended to help reduce cardiac effects. If treatment with ZEPOSIA is considered, advice from a cardiologist should be sought for those individuals:

- with significant QT prolongation

- with arrhythmias requiring treatment with Class 1a or III anti-arrhythmic drugs

- with ischemic heart disease, heart failure, history of cardiac arrest or myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, and uncontrolled hypertension

- with a history of Mobitz type II second-degree or higher AV block, sick sinus syndrome, or sino-atrial heart block

Liver Injury: Clinically significant liver injury, including acute liver failure requiring transplant, has occurred in patients treated with ZEPOSIA in the postmarketing setting. Signs of liver injury, including elevated serum hepatic enzymes and elevated total bilirubin, have occurred as early as ten days after the first dose. Obtain transaminase and bilirubin levels, if not recently available (i.e., within 6 months), before initiation of ZEPOSIA. Obtain transaminase levels and total bilirubin levels periodically during treatment and until two months after ZEPOSIA discontinuation. Patients should be monitored for signs and symptoms of any hepatic injury. Patients who develop symptoms suggestive of hepatic dysfunction should have hepatic enzymes promptly checked, and ZEPOSIA should be interrupted. Treatment should not be resumed if a plausible alternative etiology for the signs and symptoms cannot be established, because these patients are at risk for severe drug-induced liver injury.

Fetal Risk: There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Based on animal studies, ZEPOSIA may cause fetal harm. Women of childbearing potential should use effective contraception to avoid pregnancy during treatment and for 3 months after stopping ZEPOSIA. Women who become pregnant while taking ZEPOSIA may enroll in the ZEPOSIA pregnancy registry by calling 1-877-301-9314 or visiting www.zeposiapregnancyregistry.com.

Increased Blood Pressure: Increase in systolic pressure was observed after about 3 months of treatment and persisted throughout treatment. Blood pressure should be monitored during treatment and managed appropriately.

Respiratory Effects: ZEPOSIA may cause a decline in pulmonary function. Spirometric evaluation of respiratory function should be performed during therapy, if clinically indicated.

Macular Edema: S1P modulators have been associated with an increased risk of macular edema. Obtain a baseline evaluation of the fundus, including a macula, near the start of treatment with ZEPOSIA. Perform an examination of the fundus, including the macula, periodically while on therapy and any time there is a change in vision. Continuation of ZEPOSIA therapy in patients with macular edema has not been evaluated. Macular edema over an extended period of time (i.e. 6 months) can lead to permanent visual loss. Consider discontinuing ZEPOSIA if macular edema develops. The risk of recurrence after rechallenge has not been evaluated.

Patients with a history of uveitis and patients with a history of diabetes mellitus are at increased risk of macular edema during ZEPOSIA therapy.

Cutaneous Malignancies: The risk of cutaneous malignancies (including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma) is increased in patients treated with S1P receptor modulators. Skin examinations are recommended prior to or shortly after the start of treatment and periodically thereafter for all patients, particularly those with risk factors for skin cancer. Providers and patients are advised to monitor for suspicious skin lesions. If a suspicious skin lesion is observed, it should be promptly evaluated. As usual for patients with increased risk for skin cancer, exposure to sunlight and ultraviolet light should be limited by wearing protective clothing and using sunscreen with a high protection factor. Concomitant phototherapy with UV-B radiation or PUV-A photochemotherapy is not recommended in patients taking ZEPOSIA.

Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES): Rare cases of PRES have been reported in patients receiving a S1P receptor modulator. If a ZEPOSIA-treated patient develops unexpected neurological or psychiatric symptoms or any symptom/sign suggestive of an increase in intracranial pressure, a complete physical and neurological examination should be conducted. Symptoms of PRES are usually reversible but may evolve into ischemic stroke or cerebral hemorrhage. Delay in diagnosis and treatment may lead to permanent neurological sequelae. If PRES is suspected, treatment with ZEPOSIA should be discontinued.

Unintended Additive Immunosuppressive Effects From Prior Immunosuppressive or Immune-Modulating Drugs: When switching from drugs with prolonged immune effects, the half-life and mode of action of these drugs must be considered to avoid unintended additive immunosuppressive effects while at the same time minimizing risk of disease reactivation.

Severe Increase in Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Disability After Stopping ZEPOSIA: In MS, severe exacerbation of disease, including disease rebound, has been rarely reported after discontinuation of a S1P receptor modulator. The possibility of severe exacerbation of disease should be considered after stopping ZEPOSIA treatment so patients should be monitored upon discontinuation. After stopping ZEPOSIA in the setting of PML, monitor for development of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (PML-IRIS).

Immune System Effects After Stopping ZEPOSIA: After discontinuing ZEPOSIA, the median time for lymphocyte counts to return to the normal range was 30 days, with approximately 80% to 90% of patients in the normal range within 3 months. Use of immunosuppressants within this period may lead to an additive effect on the immune system, therefore caution should be applied when initiating other drugs 4 weeks after the last dose of ZEPOSIA.

Most Common Adverse Reactions (≥4%): upper respiratory infection, hepatic transaminase elevation, orthostatic hypotension, urinary tract infection, back pain, and hypertension.

Use in Specific Populations: Hepatic Impairment: Dosage adjustment in patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class A or B) is required, and use of ZEPOSIA in patients with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class C) is not recommended.

For additional safety information, please see the full Prescribing Information and Medication Guide.

© 2026 Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Zeposia is a trademark of Celgene Corporation, a Bristol Myers Squibb company. 2084-US-2600015 1/26