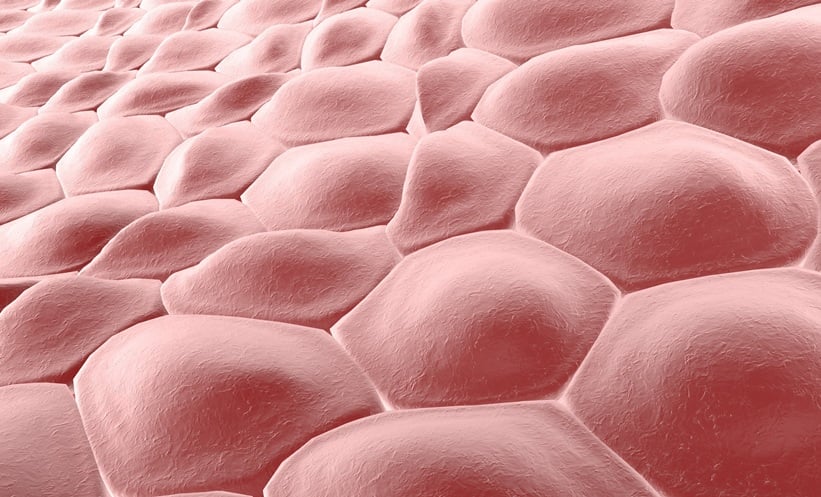

For the first time, scientists have successfully turned human skin cells into fertilisable eggs, marking a potential revolution in reproductive medicine. The study shows that eggs created through this process can be fertilised with sperm and begin early stages of embryo development, though the technology remains years away from clinical use.

How the process works

The US-led team used a technique called somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), famously used to clone Dolly the sheep in 1996. In this method, the nucleus of a skin cell is transferred into a donor egg that has had its nucleus removed.

The challenge, however, is that skin cells carry 46 chromosomes, while human eggs carry only 23. To resolve this, the researchers developed a new technique they call “mitomeiosis”, which mimics natural cell division to cut the chromosome number in half.

Using this approach, the team produced 82 developing eggs (oocytes), which were then fertilised with sperm through in vitro fertilisation (IVF). After six days, just under 9% of embryos reached the blastocyst stage – the point at which embryos could, in theory, be transferred during standard IVF. While many embryos displayed abnormalities, the researchers note that even in natural conception, only around one in three embryos progresses this far.

Hope for infertility and beyond

Co-author Paula Amato from Oregon Health & Science University said the work could one day change how infertility is treated. “It also would allow same-sex couples to have a child genetically related to both partners,” she explained.

Outside experts have described the findings as a proof of concept with profound implications. If perfected, the technology, known as in vitro gametogenesis (IVG), could provide a new route to parenthood for people who cannot produce eggs, including older women and individuals affected by medical conditions.

Still, researchers caution that clinical applications are likely at least a decade away. “The biggest hurdle is trying to achieve genetically normal eggs with the correct number and complement of chromosomes,” Amato said.

For now, the breakthrough highlights both the promise and challenges of rewriting what it means to treat infertility in the future.

Reference

Marti Gutierrez N et al. Induction of experimental cell division to generate cells with reduced chromosome ploidy. Nat Commun. 2025:DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63454-7.