INTRODUCTION

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) are two prototypic forms of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID) that share common immunological and inflammatory components and present with overlapping clinical phenotypes.

PsA is a heterogeneous disease with a varied range of clinical manifestations across key domains: peripheral arthritis affecting the extremities; axial disease affecting the spine and sacroiliac joints; enthesitis, which refers to inflammation at the sites where tendons and ligaments attach to bone; and dactylitis, defined as inflammation of the digits.1 Patients with PsA also exhibit extra-articular manifestations such as skin and nail psoriasis, uveitis (inflammation within the uvea in the eye), and inflammatory bowel disease.1 While peripheral joint inflammation is the most common feature of PsA, some patients present with a pure axial phenotype: axial inflammation in the absence of any peripheral joint involvement, where patients present with inflammatory back pain, stiffness, and characteristic imaging findings.2,3

AxSpA primarily targets the spine and sacroiliac joints, but, like PsA, may also present with systemic features including inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, and uveitis.4 The term axSpA encompasses both patients with structural damage and those with active inflammation but no visible bone changes.4 Patients are classified within the axSpA disease spectrum as having either radiographic axSpA (which includes ankylosing spondylitis [AS] when modified New York criteria are met) or having nonradiographic axSpA, in the absence of definitive sacroiliac joint changes on plain radiographs.4 In the case of nonradiographic axSpA, inflammation may be detectable by MRI.4

Dirk Elewaut, Professor of Medicine, Ghent University, Belgium, explains that one of the hallmarks of PsA and axSpA is that inflammation can be coupled to not only joint damage, but also to pathological bone remodelling.2,5 In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which is also an IMID, inflammation typically leads to only catabolic effects, having detrimental effects on cartilage and bone, and causing destruction of the joint.6 However, no pathological new bone formation is observed in RA,6 in contrast to PsA and axSpA.2,5 AS is a classic example within the axSpA spectrum, and in a subset of patients with AS, the disease may progress over time to structural damage and spinal fusion, a process known as bamboo spine due to the characteristic radiographic appearance of the vertebral column.7 The development of bamboo spine is considered a prototypical yet relatively uncommon outcome.7

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND DRIVERS OF DISEASE

The pathogenesis of PsA and axSpA is driven in part by genetic factors, particularly the HLA-B27 antigen, which has a strong association with sacroiliitis in both subsets of patients and, as Elewaut noted, is more prevalent in patients with axSpA.8 While genetics are a predisposing factor to PsA and axSpA, Elewaut explained that these diseases are not inherited in a simple Mendelian pattern; genetics contribute to risk, but it is not autosomal dominant.

Elewaut described an example of the drivers of inflammation in enthesitis, a key feature of both PsA and axSpA that is increasingly recognised as a primary event in disease development.9 A combination of genetic predisposition and environmental triggers appears to underlie this process. Elewaut explained that patients with PsA may have a lower threshold for mechanical stress, resulting in exaggerated inflammatory response at the entheses following exposure to physiological mechanical stressors.9-11 This was evaluated in an epidemiological study that examined the impact of occupational physical activity on disease progression in patients with radiographic axSpA or AS.12 The study found that individuals engaged in physically demanding jobs, such as manual labour, exhibited higher radiographic progression, measured by the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score (mSASSS; 2.18 mSASSS-units/2 years; 95% CI: 1.52–2.84), compared to those in less physically intensive occupations (1.82 mSASSS-units/2 years; 95% CI: 1.54–2.11; p=0.05). Other factors that are at play in PsA/axSpA include additional genetic risk factors, such as IL-23 receptor polymorphisms, alongside environmental influences, such as a compromised epithelial barrier in psoriatic skin, which increases microbial exposure and sustains immune activation.10 Together, these factors may contribute to a pathologically heightened immune response to otherwise physiological stress.9,11

Elewaut described the immune mechanisms driving inflammation in PsA and axSpA, and explained how they share some features with other IMIDs such as RA but also show key distinctions. Cytokines such as TNF-α are a common therapeutic target across these diseases, reflecting overlapping inflammatory pathways.13 However, there are notable differences. For example, IL-17 plays a central pathogenic role in PsA and axSpA,14-16 but targeting IL-17 in RA has not proven effective, despite promising results in preclinical models (reviewed in Taams et al.).15 This highlights that inflammation in the synovium and enthesis varies between diseases, reinforcing the idea that PsA and axSpA have distinct immune signatures, particularly involving the IL-23/IL-17 axis.

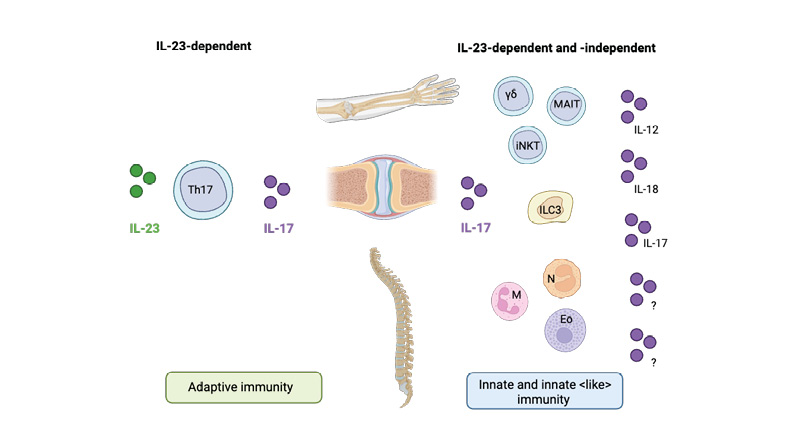

This is supported by recent evidence illustrating a non-linear relationship between IL-23 and IL-17 isoforms.17,18 IL-17A and IL-17F are important cytokines in the IL-17 family, and are pathogenically relevant in both PsA and axSpA.17,18 Traditionally, IL-17A and IL-17F production was attributed to Th17 cells by IL-23-mediated signalling.17-19 Recent evidence highlights that innate and innate-like immune cells (illustrated in Figure 1) can produce IL-17A and IL-17F independently of IL-23.17,18 Despite their overlapping functions, IL-17A and IL-17F contribute independently to chronic tissue inflammation having somehow nonredundant roles.17,18

Figure 1: Candidate cells contributing to IL-17 production via IL-23-dependent and -independent pathways in spondyloarthritis.

Th17 cells contribute to IL-17 production through an IL-23-dependent pathway, playing a role in both enthesial and peripheral inflammation in spondyloarthritis (left). Innate immune cells also contribute to IL-17 production, both through IL-23-dependent mechanisms and independently of IL-23. Several lymphoid cell types, including MAIT cells, γδ T cells, iNKT cells, and ILC3s, as well as myeloid cells, including neutrophils, mast cells, and eosinophils, have been identified as potential sources of IL-17 (right). The cytokines driving IL-17 production independently of IL-23 remain under investigation.

Eo: eosinophil; ILC3: Type 3 innate lymphoid cells; iNKT: invariant natural killer T; M: mast cell; MAIT: mucosal-associated invariant T cell; N: neutrophil; Th17: T helper 17.

Figure adapted from Rosine et al.16 Created with BioRender.com.

THE ROLE OF EARLY AND SUSTAINED CONTROL OF INFLAMMATION

Elewaut emphasised the importance of early recognition and treatment of PsA and axSpA, stating that it is crucial to “recognise this disease early and treat accordingly.” He highlighted evidence that tackling inflammation early and adequately can have a profound positive impact on bone remodelling, helping to prevent the persistent inflammation that later becomes difficult to control.20-22

However, Elewaut pointed out that early diagnosis is heavily dependent on access to rheumatology services, particularly imaging, which remains a key barrier in many settings. He also observed that the time to diagnosis varies between patients, depending on the clinical domain involved. He explained that “the diagnostic delay in peripheral disease is substantially lower than for axial disease. When you have a swollen joint, you will immediately recognise that and will go relatively fast to a doctor. When it comes to back pain, it’s more smouldering and it’s more challenging.” Nevertheless, Elewaut stressed that when patients are treated early, with a referral and diagnosis within 1 year,23 and there is clear evidence of inflammatory burden, remission rates are significantly higher.23 He continued to explain that improvement is already visible in clinical practice, where he has increasingly observed milder forms of disease compared to 2 decades ago, likely due to a combination of more effective therapies and the shift towards earlier intervention.24

A CLINICAL VIEW OF REMISSION IN PSORIATIC ARTHRITIS AND AXIAL SPONDYLOARTHRITIS

Remission in PsA and axSpA is currently defined as the absence of clinical and laboratory evidence of significant inflammatory disease.25 It is considered the primary treatment goal of the rheumatologist and reflects a meaningful reduction or disappearance of disease activity across the relevant domains. However, assessing remission is complex due to the heterogeneous nature of these conditions.25 Different domains may be active at different times and may respond differently to treatment.20 Maria Antonietta D’Agostino, a Professor of Rheumatology at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Rome, Italy, describes remission as “a moment in the disease life of the patient,” where all aspects of the disease are under control. Indeed, the impact of the clinical manifestations due to the involvement of different domains may vary in individual patients, with certain symptoms perceived as more burdensome or functionally limiting than others.25 As a result of this, evaluating remission requires a nuanced, multidimensional approach that captures the fluctuating activity across all affected areas, taking the patient’s views into consideration.

D’agostino explained that remission can be conceptualised across three areas: clinical, imaging, and tissue remission.25,26 Clinical remission refers to the absence of signs and symptoms of active disease, as measured by validated clinical assessments, serological markers, and patient-reported outcomes.25 There are multiple scores and composite indices for clinically evaluating psoriatic arthritis.25 These include, but are not limited to, the Minimal Disease Activity (MDA),27 the Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA),28 and the Psoriatic Arthritis Disease Activity Score (PASDAS).29 All three assessments are composite scores that encompass multiple indices, including patient-reported outcomes such as tender joints, pain scores, and non-articular symptoms. The DAPSA and PASDAS also include laboratory markers for inflammation, such as a blood test for C-reactive protein. Two commonly used measures for clinically evaluating axSpA are the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI)30 and the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS).31,32 Both scores include patient-reported outcomes such as back/spinal pain, morning stiffness, and peripheral joint pain and swelling. The ASDAS also includes C-reactive protein.31

Imaging remission denotes the lack of detectable inflammation on imaging modalities such as X-ray, MRI, or ultrasound, which can reveal disease activity not captured through clinical evaluation alone. MRI or ultrasound imaging of the joints can reveal inflammation, and X-ray imaging can evaluate structural damage caused by chronic inflammation.32 D’Agostino described how imaging could play a key role in evaluating remission in domains where a complete improvement can be visualised, such as joints, tendons, and entheses, but also the skin, which can appear visually ‘normal’, although evaluation through deep imaging of the skin shows residual inflammation33 that D’Agostino highlighted may result in a flare if a treatment regimen is changed or reduced. D’Agostino explained how such discordance between clinical and imaging findings is often referred to as subclinical remission,33 and advocated that this should be considered by clinicians when assessing remission in patients.

D’Agostino noted that tissue remission may represent the highest level of disease control in PsA and axSpA, referring to the resolution of inflammation at the cellular and molecular level.26 Although not routinely assessed in clinical practice, it can be evaluated through tissue analyses such as skin, synovial, or enthesial biopsies, currently used primarily in research settings.34,35 D’Agostino explained that, unlike clinical or imaging remission, tissue remission offers the closest approximation to a true cure, in which underlying pathophysiological processes are reversed, ideally without the need for ongoing treatment. “The cure is the restoring of the natural homeostasis of the patient, without any treatment,” she noted. However, the persistence of residual tissue-level inflammation, despite clinical and imaging remission, may contribute to disease recurrence after treatment withdrawal.26,36 Currently, no therapy, aside from experimental approaches such as CAR-T cell therapy in some autoimmune diseases, has been shown to reset the immune system sufficiently to sustain tissue remission without continued pharmacological support.26,37,38

D’Agostino emphasised that achieving true remission may require alignment across clinical, imaging, and tissue levels. She highlighted the importance of the use and continued development of appropriate, domain-specific instruments to accurately assess remission at each level. While recognising the potential of tissue remission to define long-term therapeutic success, she advocated for clinical and imaging remission as the most practical and achievable targets in current practice.

BARRIERS TO ACHIEVE AND MAINTAIN REMISSION IN CURRENT CLINICAL PRACTICE

D’Agostino explained that remission is often not achieved due to a combination of factors, including patient factors, disease manifestations, and comorbidities. Patient-related factors can significantly influence both the perception of remission and the actual achievement of symptom control. Importantly, D’Agostino noted that clinical indicators of remission often improve before the patient subjectively feels better, underlining the need to consider the patient’s perception of disease control alongside objective measures. In IMIDs like PsA, chronic pain may persist even when inflammation is well managed.39,40 As D’Agostino noted, if remission were defined solely by the absence of pain, it could remain an unattainable goal for some patients. In addition, non-adherence to treatment regimens can undermine therapeutic effectiveness. This may stem from various issues, including difficulty accepting the disease, concerns about long-term treatment, or intolerance to side effects.

The manifestations of disease can also be a barrier to remission. D’Agostino explained that the choice of treatment and its sequence is critical because certain therapies may work preferentially against the differential immunopathology of certain domains,16 and further, may not work as well if the disease has already caused significant damage or if inflammation has been poorly controlled for an extended period of time.20-22

Achieving and maintaining remission in PsA and axSpA can be complicated by the presence of comorbidities, which can influence drug selection, treatment response, safety, and overall disease burden.1,32,41 PsA is associated with obesity, Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, fatty liver, and cardiovascular disease.41 D’Agostino explained that these comorbidities are not always considered by healthcare professionals, and highlighted the importance of treating the patient “as a human,” taking comorbidities into account and considering implications for treatment on a case-by-case basis.

ALIGNING PATIENT AND PRACTITIONER TREATMENT GOALS

Aligning patient and practitioner treatment goals in PsA and axSpA requires a shared and multidisciplinary approach that recognises the complexity and heterogeneity of these conditions across the patient population. D’Agostino explained that “the patient is not just their disease, and we have to learn how to understand the impact of the disease on normal life,” highlighting the critical need to involve the patient, in a shared decision-making approach, from the very start of the diagnosis, treatment, and throughout their journey, including during periods of remission and disease flare. Furthermore, D’Agostino commented that patients should be empowered to recognise when disease activity returns, as symptoms like chronic pain can persist even in the absence of active inflammation.39,40 She emphasised that the ongoing pain must not be dismissed simply because there is no evidence of active disease, as the impact on quality of life can be significant.40 Ultimately, patients and practitioners may have different definitions of remission. While patients often associate remission with being pain-free, clinicians understand that residual symptoms may remain. Transparent conversations are essential to set realistic expectations that foster mutual understanding, and respect for the patient’s lived experience.

One of the key challenges in treating PsA and axSpA lies in their multidimensional nature, with symptoms affecting multiple domains such as joints, spine, skin, and entheses. As D’Agostino explained, treatment often needs to prioritise one domain at a time, depending on the most pressing clinical or patient-reported concerns. It is therefore essential to involve patients in this decision-making process, as they may prioritise symptom reduction differently. What matters most to the clinician may not align with what impacts the patient’s daily life. The treat-to-target (T2T) approach provides a standardised way of aligning patient and practitioner goals.

THE TREAT-TO-TARGET APPROACH: CLINICAL INSIGHTS AND CHALLENGES

T2T is defined as the frequent assessment of disease activity with therapy adjusted accordingly until low disease activity or remission is achieved.20 The benefits of this strategy were first demonstrated in psoriatic arthritis through the TICOPA trial, which showed that tight control improved joint outcomes for newly diagnosed patients, with no unexpected adverse events reported.42 D’Agostino noted that the T2T approach also helps to structure alignment of patients and healthcare professionals, as priorities often vary between individuals. T2T is a frequently used strategy in numerous inflammatory diseases including diabetes.20

However, D’Agostino acknowledged that the approach is not always implemented in clinical practice,43 often due to limitations within national healthcare systems. She suggested that involving patients more in disease evaluation, such as through remote symptom reporting, could help overcome some of these barriers. Although T2T remains a guideline rather than a mandate, early implementation may increase the likelihood of achieving and sustaining remission.

In axSpA, while the concept is promising, several challenges remain. Elewaut emphasised the need for more research to guide T2T use in axSpA and cautioned against relying solely on numerical values like the ASDAS. He advocated for a holistic view of the patient, while still following a structured T2T approach. Ideally, the treatment target should be based on a composite index that incorporates clinical manifestations across all domains, objective measures of inflammation and structural progression markers, alongside patient reported outcomes for quality of life and physical function, a sentiment that is shared in multiple studies.25,32,44

CURRENT TREATMENT LANDSCAPE AND CHALLENGES

Treatment guidelines for both PsA and axSpA emphasise a stepwise, patient-centred approach.1,20 These are outlined in a 2023 update to the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR)recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies.45

For axSpA, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are generally the first-line treatment that relieves symptoms but does not modify disease progression.1,45 For PsA, conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARD), such as methotrexate and leflunomide are often recommended initially.1 In cases where these treatments are insufficient, biologics or targeted synthetic DMARDs may be considered for both conditions.1 EULAR recommendations for second-line therapy of PsA include the use of biological DMARDs, including agents targeting IL-23p40, IL-23p19, IL-17A and IL-17A/F.45 Disease manifestations are considered during treatment decision making, including musculoskeletal involvement, such as axial disease or enthesitis, and extra-musculoskeletal manifestations like inflammatory bowel disease or uveitis.45

D’Agostino and Elewaut both highlighted the importance of defining the starting point for the disease and considering which domain dominates the clinical picture, which can tailor the treatment response. In many cases, PsA and axSpA are joint diseases, so conventional NSAIDs and conventional synthetic DMARDs (methotrexate and leflunomide) are important early on in treatment.1 For axSpA, D’Agostino cautioned against delaying effective therapy by relying on conventional synthetic DMARDs, which have limited efficacy in axial disease as per ASAS-EULAR guidelines.46 Instead, she advocated for the early initiation of biologic DMARDs in patients unresponsive to NSAIDs, to avoid the loss of disease control.

Elewaut advocated for a remission-focused treatment approach, urging clinicians: “Don’t be happy with a partial response.” Achieving and maintaining a sustained treatment response is a key goal in the management of these diseases,47 particularly given the chronic and often progressive nature. Sustained efficacy is crucial not only for long-term symptom control, but also for minimising structural joint damage and preserving quality of life.47 He highlighted the challenge posed by the lack of predictive tools for treatment response, emphasising the need for thoughtful, responsive management to ensure timely treatment adjustments and prevent inflammatory flares and subsequent structural progression.

Elewaut also noted that in clinical practice, reduced efficacy is often observed when patients are cycled through multiple therapies, highlighting the need for treatments that maintain effectiveness over time. Recent clinical experience suggests that some newer therapies may offer consistent effectiveness, even in patients with prior biologic exposure.48,49 The mechanisms behind this retained activity are not yet understood, but Elewaut hypothesised that they are likely to work on separate pathways or cells than other currently used therapies, avoiding the resistance or tolerance acquired against previous therapies.

FUTURE OUTLOOKS: A PERSONALISED AND DOMAIN-SPECIFIC TREATMENT APPROACH

Both Elewaut and D’Agostino emphasised the need for a more personalised, domain-specific approach to treatment, grounded in a deeper understanding of disease mechanisms. Despite the ongoing development of new treatments and updates to recommendations, many patients fail to respond or have a partial response to treatment.50 In the event of nonresponse, patients often shift and cycle through different treatment options, a process that can increase the risk of structural progression and ultimately lead to poorer treatment outcomes.50,51 Elewaut explained that, for these patients, it is often important to go back to the drawing board and confirm the appropriate diagnosis. However, in the future, understanding the underlying mechanisms of inflammation may support more targeted therapies and enable earlier, more sustained control of disease activity. Research in this area is more advanced for RA, where several molecular pathways driving inflammation have already been identified as potential targets for future therapy.35 These include drivers related to adaptive immunity, such as disrupted balance between effector and regulatory T cells; synovial tissue-specific factors, such as mesenchymal cell priming that promotes local cytokine production within joints; and systemic influences, particularly the gut–brain axis.26 This latter area focuses on how stress and RA-related changes in gut permeability may contribute to immune dysregulation and disease progression.26

Achieving this would require advances in diagnostic precision, including validated biomarkers of underlying immunopathology and the ability to classify patients using mechanistic definitions of disease at a molecular and cellular level.52 In addition, a robust, quantitative measure of treatment effectiveness would be essential to accurately define cure.52 Such progress would also support the development of predictive tools, which Elewaut highlighted as crucial for matching patients to the most appropriate therapy based on their individual immune profiles. Elewaut noted that tissue-level insights, such as those gained from synovial biopsies, could also inform drug development by identifying specific inflammatory pathways, though less invasive techniques would be preferable. D’Agostino echoed the value of a tailored strategy, suggesting that integrating assessments of tissue remission and domain-specific inflammatory mechanisms could optimise current treatment selection and drive the discovery of novel, domain-targeted therapies. D’Agostino proposed that this mechanistic understanding could ultimately bring the field closer to a sustained drug-free remission,26 recognising that inflammation may differ between disease domains and individuals.

KEY TAKE-HOMES

A proactive, patient-centred approach to managing PsA and axSpA is essential for achieving optimal outcomes. Elewaut emphasised the importance of early recognition of disease and timely, appropriate treatment for PsA and axSpA, guided by a T2T strategy, while D’Agostino reiterated the need for a communicative treatment approach, ensuring that remission is evaluated collaboratively and sustained across multiple domains. D’Agostino concluded by advocating for incorporating both clinical and imaging assessments into treatment decisions to help confirm true disease control and inform long-term management.

| Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard. Adverse events should also be reported to UCB Pharma Ltd. on 0800 279 3177 or via email at [email protected]. |

Date of preparation: November 2025