Meeting Summary

Over the past two decades, thoracic oncology has undergone a profound transformation, moving from limited chemotherapy regimens to highly personalised strategies utilising targeted therapies and immuno-oncology (I-O). This symposium, featuring three leading experts, reviewed the current management of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (mNSCLC) by focusing on three critical areas: optimising I-O-based regimens, particularly for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) tumour expression <1%; the evolving landscape of KRASG12C inhibition and resistance; and the promise of novel drug modalities, including bispecific antibodies, select epigenetic modifiers, and antibody–drug conjugates (ADC). Data presented reinforced the durable, long-term survival achieved with dual I-O and chemotherapy regimens in patients with PD-L1 negative disease and other difficult-to-treat subgroups, the clinical efficacy of approved KRASG12C inhibitors and those under investigation, and the exciting potential of novel targets and treatments for the treatment of both NSCLC and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). Key discussions highlighted that, while outcomes for NSCLC have dramatically improved, challenges remain in achieving curative outcomes, managing resistance mechanisms, and developing effective biomarkers beyond PD-L1 status.

Introduction

The symposium presentation explored the established I-O landscape for first-line (1L) mNSCLC without actionable genomic alterations (AGA), the emerging landscape for KRASG12C-mutated NSCLC, and the development of various novel targets and agents for both NSCLC and SCLC. A major focus of the symposium was the dynamic nature of the treatment landscape for lung cancer, highlighting the need for physicians to be well-informed about both established therapies and emerging modalities in order to make informed treatment decisions for their patients.

Informing Optimal Treatment Decisions with Immuno-oncology-Based Regimens for Patients with Programmed Death-Ligand 1 <1% Metastatic Non-small Cell Lung Cancer

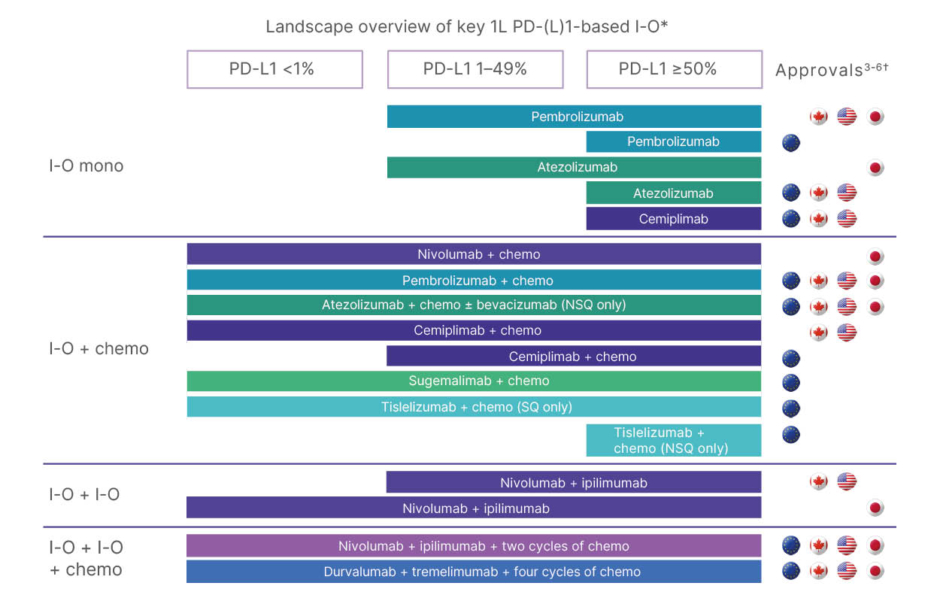

Rosalyn Juergens, Medical Oncology, Juravinski Cancer Centre, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, began the symposium with an overview of the increasing number of 1L treatment options available for patients with mNSCLC without AGAs based on tumour PD-L1 expression levels. NSCLC accounts for nearly 90% of lung cancer cases, with most patients presenting with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis. Select genomic alterations in NSCLC allow for targeted therapy use where available. However, in patients with no known AGAs and those with AGAs for which there is no approved treatment in 1L (e.g., KRAS), tumour PD-L1 expression is key to informing treatment decisions in 1L mNSCLC.1,2 For patients with PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score (TPS) ≥50%, various I-O monotherapies and I-O+chemotherapy combinations are commonly used. For patients with PD-L1 1–49% or PD-L1 <1%, combination regimens involving I-O+chemotherapy or dual I-O+chemotherapy, summarised in Figure 1, represent key standards of care.3-6

Figure 1: Landscape overview of key first-line programmed death-ligand 1-based immuno-oncology agents

approved for treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer.

*This diagram is intended for illustrative purposes only, and the treatment algorithm may vary by region.

†Refer to local materials such as prescribing information and/or Summary of Product Characteristics for each agent.

1L: first line; chemo: chemotherapy; I-O: immuno-oncology; mono: monotherapy; NSQ: non-squamous; PD-1: programmed death receptor-1; PD-L1: programmed death ligand 1; SQ: squamous.

Outcomes for patients with tumour programmed death-ligand 1 <1%

Juergens presented data for the KEYNOTE-189 trial, noting that the median overall survival (OS) of 22 months with pembrolizumab+chemotherapy in the intention-to-treat population was more than double that observed with placebo+chemotherapy in the same population. However, the median OS was numerically lower in patients with TPS PD-L1 <1%. The 5-year OS rate was 19% with pembrolizumab+chemotherapy across all levels of PD-L1 expression and 10% in the PD-L1 <1% subgroup.7 This was followed by 5-year data from a pooled analysis of KEYNOTE-189 and KEYNOTE-407. At Year 5, OS rates were 13% and 9%, for pembrolizumab+chemotherapy and placebo+chemotherapy, respectively, demonstrating limited clinical benefit for 1L pembrolizumab+chemotherapy treatment for patients with PD‑L1 tumour expression <1%.8 Similarly, real-world data demonstrated that patients with tumour PD-L1 expression <1% had poorer long-term outcomes compared with those with tumour PD-L1 expression ≥50% receiving 1L I-O therapy+chemotherapy. At Year 5, OS rates were 11% and 25%, respectively, in patients with mNSCLC.9 These data demonstrate a remaining unmet need for treatments with long-lasting efficacy in patients with tumour PD-L1 expression <1%.

Dual immuno-oncology-based regimens for patients with PD-L1 <1%

Anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and anti-PD-(L)1 treatments have distinct but complementary mechanisms of action to reactivate the immune system. Anti-CTLA-4 treatment induces de novo anti-tumour responses and promotes the emergence of memory T cells, while anti-PD-(L1) treatment restores anti-tumour T cell function and enhances pre-existing T cell response.10-12 The combination of dual I-O and chemotherapy has demonstrated long-term benefit in the 1L setting in NSCLC.13,14

Juergens discussed two key trials that evaluated dual I-O–based regimens: CheckMate 9LA and POSEIDON. In CheckMate 9LA, the 5-year OS rate in patients with tumour PD-L1 <1% was 22% for nivolumab+ipilimumab+chemotherapy versus 8% for chemotherapy alone, and the 6-year OS rates were 20% and 7%, respectively.13 In the POSEIDON trial, the 5-year OS rate was 6% in patients treated with durvalumab+tremelimumab+chemotherapy versus 4% for chemotherapy alone.14

While the median duration of response (DOR) with single I-O+chemotherapy in KEYNOTE-189 was 10.8 months, the median DOR for dual I-O+chemotherapy in CheckMate 9LA was almost 18 months.7,13 Real-world data from Germany in the FINN study are consistent with outcomes from CheckMate 9LA, indicating that these durable outcomes are achievable in routine practice.15

Data show that the rate of high-grade (Grade 3/4) treatment-related adverse events (TRAE) for dual I-O+chemotherapy (CheckMate 9LA/POSEIDON) is similar to that of single agent I-O+chemotherapy (KEYNOTE 189), approximately 50% of patients. Crucially, the rate of treatment discontinuation due to TRAEs is consistent across these regimens (20–26% of patients), and treatment-related deaths remain rare.7,13,16 In an exploratory analysis, discontinuation due to TRAEs did not appear to negatively impact survival rates for patients in CheckMate 9LA.13 Analysis of real-world safety data found that the safety experiences of patients treated with 1L nivolumab+ipilimumab±chemotherapy were numerically similar to those treated with other approved I-O+chemotherapy combination therapies, supporting the use of these regimens in routine practice.17

Building Momentum in Research of Targeted Therapies for Patients with KRASG12C-Mutated Non-small Cell Lung Cancer

Pasi Jänne, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, opened with an overview of the prevalence of KRAS mutations, which account for 25% of mutations in lung adenocarcinoma, with KRASG12 being the most common subtype.1,18 KRAS acts as a molecular ‘ON/OFF’ switch. In its ‘ON’ state, GTP binding to KRAS results in the activation of several cell-signalling pathways promoting cell growth and survival. The G12C mutation causes a persistent ‘ON’ state, and until recently, KRAS was considered undruggable.19 Discovery of the switch II binding pocket led to the development of KRASG12C-selective inhibitors, which irreversibly lock KRASG12C in the ‘OFF’ state.19,20

KRASG12C Inhibitors

Two KRASG12C inhibitors, adagrasib and sotorasib, received accelerated/conditional approvals in the USA and EU based on Phase II trials (KRYSTAL-1 and CodeBreak 100, respectively).21,22 Confirmatory Phase III trials KRYSTAL-12 and CodeBreak 200 compared these inhibitors to docetaxel in patients with locally advanced or mNSCLC who had prior treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy and anti-PD-(L)1 therapy.22,23 In the KRYSTAL-12 trial, progression-free survival (PFS) improved from 3.8 to 5.5 months versus docetaxel, with an objective response rate (ORR) of 32% and a median DOR of 8.3 months with adagrasib.23 In KRYSTAL-1, an intracranial ORR of 42% was observed in patients with untreated central nervous system (CNS) metastases; this data set resulted in the only National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Category 2A recommendation for patients with KRASG12C mNSCLC with CNS metastases.24,25 CodeBreak 200 demonstrated improved PFS with sotorasib versus docetaxel (5.6 versus 4.5 months). There was an ORR of 28% and a median DOR of 8.6 months with sotorasib.22 Sotorasib has an NCCN Category 2B recommendation for patients with KRASG12C mNSCLC with CNS metastases.25

KRASG12C Inhibitors in Combination with Other Therapies

Improving efficacy with KRASG12C inhibitors remains crucial. KRASG12C inhibitor monotherapy can lead to resistance via multiple mechanisms.26 Combination therapies are being explored to circumvent these resistance pathways, including KRASG12C inhibitors combined with I-O±chemotherapy or anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapies.27-35

Early data for I-O and KRASG12C inhibitors in the 1L setting are promising, particularly in patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50%. For adagrasib+pembrolizumab (KRYSTAL-7, Phase II), the response rate was 61%, with a median PFS of 27.7 months in patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50%.27 Separately, in a pooled analysis of Phase I LOXO-RAS 20001 and Phase III SUNRAY-01, there was a 78% response rate with olomorasib and pembrolizumab in patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥50%.28 Calderasib+pembrolizumab demonstrated a response rate of 77% in patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥1% in the Phase I trial KANDLELIT-001.29 KRASG12C inhibitors+pembrolizumab±chemotherapy are being explored in numerous Phase III trials, e.g., KRYSTAL-7, KRYSTAL-4, SUNRAY-01, KRAScendo-2, and KANDLELIT-004.27-31

However, initial combinations of sotorasib with I-O (atezolizumab and pembrolizumab) as part of the CodeBreak 101 trial exhibited high rates of Grade 3 and 4 hepatic toxicities, despite attempts to reduce toxicity via a ‘lead-in’ phase.32 Jänne highlighted that he believes that combination strategies integrating I-O and KRAS inhibitors will ultimately be fruitful, noting that toxicity issues may be specific to certain drugs rather than the target itself.

Though combinations of sotorasib with I-O in CodeBreaK 101 exhibited high rates of adverse events, combining sotorasib with chemotherapy in a separate arm of the same trial demonstrated a 65% response rate and a PFS of 10.8 months.33 The ongoing Phase III Code Break 202 trial is investigating sotorasib and chemotherapy in patients with PD-L1 TPS <1%.34 Combinations of KRASG12C inhibitor+EGFR inhibitors are also being investigated. The KROCUS study, which evaluated fulzerasib with cetuximab, achieved a response rate of 80% and a modified PFS (mPFS) of 12.5 months.35

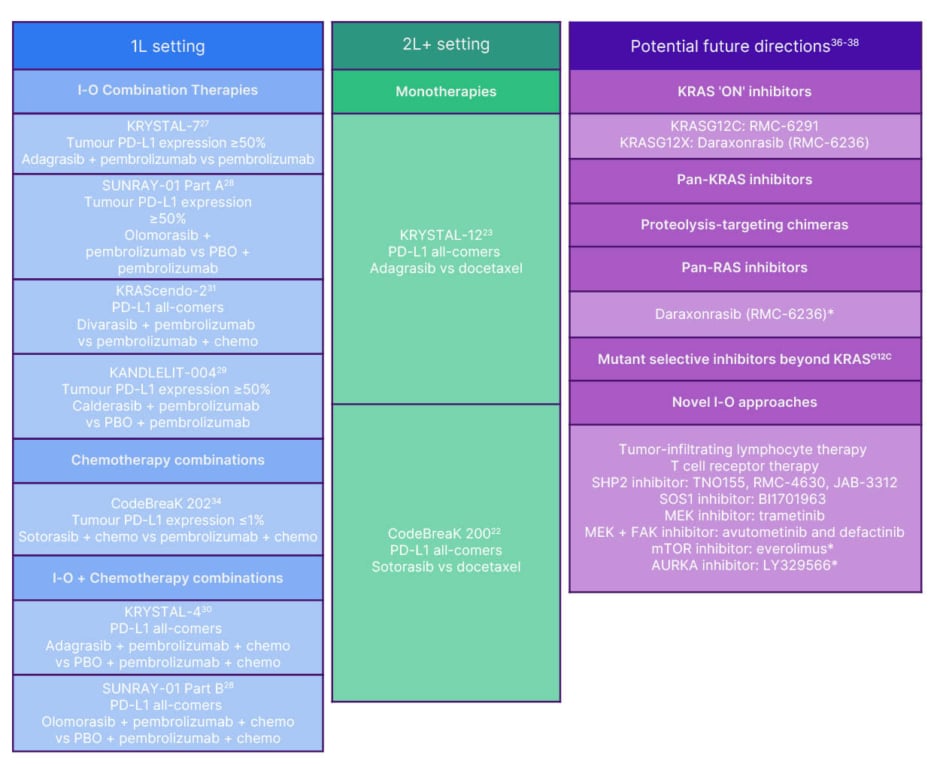

Selected ongoing Phase III trials of KRASG12C inhibitors in both 1L and 2L+ NSCLC and the potential future directions of KRAS-directed therapy are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Summary of select ongoing Phase 3 trials of KRASG12C inhibitors for KRASG12C non-small cell lung cancer and potential future directions for KRAS-directed therapy.

*Being investigated in solid tumours.

1L: first line; 2L: second line; AURKA: aurora kinase A; chem: chemotherapy; FAK: focal adhesion kinase;

I-O: immuno-oncology; MEK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin;

PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; PBO: placebo; PROTAC: proteolysis targeting chimera;

SHP2: SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase 2; SOS1: son of sevenless homologue 1; vs: versus.

Relentless Research for Novel Treatment Options: Meeting the Diverse Needs of Patients with Lung Cancer

John Heymach, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA, launched this segment by emphasising that, while significant progress has been achieved, the lack of curative outcomes highlights the need for a diverse range of new therapeutic modalities.

Novel Treatment Combinations and Modalities Shaping the Future of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment

Beyond PD-L1 status, co-occurring genomic alterations can play a role in outcomes for patients with NSCLC and thus help guide treatment decisions. For example, co-mutations in STK11 or KEAP1 are known to drive resistance to PD-(L)1 regimens in NSCLC.

Patients with KEAP1 wild-type tumours have a median OS of 16.6 months when treated with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)+chemotherapy, versus 7.6 months for those with KEAP1 mutations.39 These co-mutations also impact KRASG12C inhibitor efficacy.26 Intriguingly, while STK11/KEAP1 mutations are associated with resistance to anti-PD-1, they appear associated with greater sensitivity to anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Data from POSEIDON showed that, in the STK11/KEAP1 mutant subgroup, there was a greater relative benefit from adding tremelimumab to durvalumab+chemotherapy (hazard ratio: 0.64), suggesting that genomics can help providers select the most appropriate I-O regimen.39

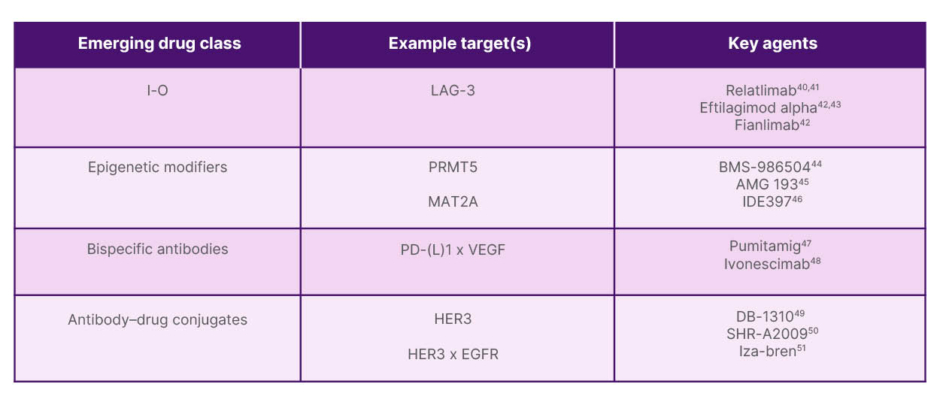

Novel therapeutic approaches and emerging drug classes are being explored to improve outcomes in mNSCLC, with select classes, targets, and agents summarised in Figure 3. The first among these to be discussed by Heymach was lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) immunotherapy. LAG-3 negatively regulates T cell proliferation and function. Combining LAG-3 and PD-1 inhibition has the potential to enhance antitumour activity through a synergistic effect.42,52 Relatlimab (approved for melanoma in combination with nivolumab) and fianlimab are anti-LAG-3 agents currently being investigated, while eftilagimod alpha is a soluble LAG-3 agent under investigation.42 In the RELATIVITY-104 study, relatlimab+nivolumab+chemotherapy showed improved median PFS (6.7 versus 6.0 months) and ORR (51.3% versus 43.7%) compared to nivolumab+chemotherapy alone, with no dramatic increase in adverse events. Survival benefit was observed in patient subgroups, with an mPFS of 9.8 versus 6.1 months in patients with tumour PD-L1 ≥1% and an mPFS of 8.3 versus 6.0 months in patients with non-squamous histology.40 Phase III trials of relatlimab (RELATIVITY-1093) and eftilagimod alpha (TACTI-004) are currently ongoing.41,43

Figure 3: Emerging drug classes and key targets being investigated in non-small cell lung cancer.

EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; HER3: human epidermal growth factor receptor 3; LAG-3: lymphocyte-activation gene 3; MAT2A: methionine adenosyltransferase 2A; PD-1: programmed death receptor-1; PD-L1: programmed death ligand 1; PRMT5: protein arginine N-methyltransferase 5; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

Next, Heymach shifted focus to protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) and methionine adenosyltransferase 2A (MAT2A) inhibitors, which are examples of epigenetic modifiers. PRMT5 inhibitors are an exciting new class of drug for tumours with MTAP deletions. The MTAP gene, commonly deleted alongside CDKN2A, is associated with poor prognosis and immunotherapy resistance. The deletion creates a vulnerability: inhibiting PRMT5 leads to a build-up of methylthioadenosine (MTA), which forms a complex with PRMT5 that is highly enriched in tumour cells. This complex is a synthetic lethal target that can be inhibited by MTA-cooperative PRMT5 inhibitors.53 Several second-generation PRMT5 inhibitors are showing substantial activity in Phase I/II trials across MTAP-deleted tumours. In a Phase I trial, BMS agent BMS-986504 (Bristol Myers Squibb, Princeton, New Jersey, USA) demonstrated 29% ORR, 10.5 months median DOR, and 80% disease control rate in patients with pretreated mNSCLC.44 Amgen’s agent AMG-193 (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, California, USA) demonstrated 11.7% ORR and 8.3 months median DOR in the Phase I trial MTAPESTRY 101.45 Ideaya Biosciences’ MAT2A inhibitor IDE397 (Ideaya Biosciences, South San Francisco, California, USA) demonstrated an ORR of 38% (squamous) and 22% (non-squamous), and high disease control rate in the Phase I trial IDE397-001.46 These drugs are generally well-tolerated, with Grade ≥3 adverse event rates ranging from 14–18%.44-46 PRMT5 inhibitors are rapidly moving into Phase II/III trials as monotherapies and in combination with pembrolizumab and/or abemaciclib (cyclin-dependent kinase [CDK]4/6 inhibition), including Phase II/III trial of BMS-986504+pembrolizumab+chemotherapy in 1L MTAP-del NSCLC (MountainTAP-29).54

Bispecific antibodies targeting both PD-(L)1 and VEGF were the next emerging drug class discussed by Heymach. This dual targeting of PD-(L)1 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is hypothesised to both enhance immune response and antiangiogenesis and may be more effective than targeting either pathway alone.55 In 1L NSCLC, median PFS was 13.6 months, and ORR was 47.1% with pumitamig, an anti-PD-L1 x VEGF bispecific antibody in a Phase I/IIb study.47 A randomised study in China (HARMONi-2) demonstrated a striking difference in median PFS with ivonescimab, an anti-PD-1 x VEGF bispecific antibody (11.1 months with ivonescimab versus 5.8 months for pembrolizumab alone).48 These drugs have tolerable safety profiles as single agents, with rates of Grade ≥3 TRAEs between 20–29%.47,48 The Phase II/III global study ROSETTA-LUNG-02 is investigating pumitamig combinations with chemotherapy and/or pembrolizumab, and multiple global Phase III studies (HARMONi-3 and HARMONi-7) are currently investigating ivonescimab combinations with chemotherapy and/or pembrolizumab.56-58

ADCs utilise an antibody to target specific cells, which are internalised, leading to the release of a cytotoxic payload to kill tumour cells, often with a bystander effect on nearby cells.59 Monospecific anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)3 ADCs under investigation for treatment of EGFR-mutant NSCLC include DB1310 and SHR 82009, which have shown ORRs of 28% and 36%, respectively, in early phase trials.49,50 The drug iza-bren (BLB 01D1), a potential first-in-class EGFR x HER3-targeting bispecific ADC with a topoisomerase I inhibitor (Ed-04) payload, demonstrated a high 54% response rate in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC who have progressed on third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors but are chemo naive in a Phase I/II trial in China (NCT05194982/NCT05880706).51 Toxicities across this class of drugs are largely haematologic.49-51

Novel Strategies to Address Unmet Need in Small Cell Lung Cancer

There remains an unmet need for novel therapies with long-term outcomes and manageable safety in SCLC. Adding anti-PD-(L)1 regimens to platinum-based chemotherapy has only shown modest OS improvement in patients with 1L extensive-stage SCLC, though recently, lurbinectedin+atezolizumab maintenance further improved survival.60-62 The bispecific T cell engager tarlatamab has recently demonstrated improved survival over chemotherapy in the relapsed/refractory setting and is under investigation in the 1L setting.63 Several innovative approaches are currently under rigorous investigation for SCLC, including innate immune inducers, bispecific antibodies, ADCs, and radiopharmaceuticals.

Atigotatug (anti-fucosyl-monosialoganglioside-1 [Fuc-GM1]) is a specific innate immune inducer currently being investigated for the treatment of SCLC. Targeting the ganglioside Fuc-GM1 has the potential to trigger various anti-tumour mechanisms, including complement-dependent cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis.64

As in NSCLC, combining checkpoint blockade (PD-1/PD-L1) with antiangiogenesis (VEGF inhibition) is currently under investigation in SCLC for treatment with the use of bispecific PD-(L)1 x VEGF antibodies pumitamig (BNT327) and ivonescimab.55

Numerous ADCs against promising new targets are in development for the treatment of SCLC, including ifinatamab deruxtecan (I-DXd), ZL-1310, and sacituzumab govitecan.65

Radiopharmaceuticals, antibodies linked to a radionucleotide or radioactive compound, combine the precise targeting of a monoclonal antibody with the potent cytotoxic effect of radiation. Among those discussed was RYZ101 (225Ac-DOTATATE), a first-in-class, highly potent alpha-emitting radiopharmaceutical therapy being developed for somatostatin receptor Type 2 positive solid tumours, including SCLC.66

These novel treatment options and modalities represent relentless research efforts aimed at meeting the diverse needs of patients with lung cancer and overcoming the unmet need for improved long-term outcomes in SCLC.

Patient Cases and Panel Discussion

Two patient cases were discussed by faculty during the symposium, highlighting treatment options and the importance of making informed decisions about patient treatment.

The first case, presented by Juergens, focused on I-O treatment options, and the audience was asked to select whichI-O-based therapy regimen they would choose for the patient with TTF1+ metastatic adenocarcinoma. The second case presented by Jänne focused on 1L treatment options for a hypothetical patient with KRASG12C mutations and tumour PD-L1 expression <1%. Questions for the audience included whether they would choose standard-of-care I-O+chemotherapy or enrolment in a clinical trial of the treatment options discussed earlier in Jänne’s presentation.

The interactive discussion with all faculty members focused on several critical challenges in thoracic oncology. Audience questions spurred discussions about the need for biomarkers beyond PD-L1, the exciting future for KRAS therapy, the desire for the presence of co-mutations STK11 and KEAP1 within routine next-generation sequencing panels, and brain penetrance of large molecules and inclusion of patients with baseline brain metastases in clinical studies.

The symposium concluded by addressing the most significant hurdles remaining in lung cancer treatment. Despite advances with next-generation drugs, a residual drug-tolerant population exists, and anti-tumour immunity remains largely unutilised in oncogenic driver settings (e.g., PD-1 inhibitors add limited benefit). Unlike the chemo-I-O setting, which produces a plateau on the survival curve, targeted therapies historically do not cure patients with advanced oncogene-addicted lung cancer. Better biomarkers are needed to select patients for various combination strategies, determine who requires treatment escalation in locally advanced disease, and understand complex drug modalities like ADCs. For ADCs, optimising treatment requires understanding not just of the cell surface target, but also payload sensitivity (e.g., sensitivity to topoisomerase inhibitors versus tubulin inhibitors). Finally, as long-term survival rates increase due to durable I-O and combination regimens, the challenge of managing survivorship and determining optimal duration of follow-up for long-term survivors is becoming increasingly relevant.