| Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk or search for MHRA yellowcard in the Google Play or Apple App store. Adverse events should also be reported to Theramex on [email protected] or Tel: +44 (0)333 0096795 |

Meeting Summary

The symposium included presentations from Antonio Cano from the Department of Paediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Valencia, Spain; Petra Stute from the Department of Gynaecological Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine, University Hospital of Bern, Switzerland; and Marco Gambacciani from Clinica San Rossore, Pisa, Italy. Content on this topic compiled by Nick Panay, from the Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction, Imperial College London, UK, was presented by Stute at the symposium.The aim of the symposium was to discuss the role of individualised menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) in long-term cardiovascular health, osteoporosis prevention, and breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women, highlight clinical considerations when selecting different progestogens, and review recent evidence on the risk–benefit profile of MHT in real-world settings.

Cano opened the session by describing the observed decline in MHT use among women with menopausal symptoms and discussed potential long-term implications of this trend. Stute then addressed the importance of tailoring MHT to individual patient needs and introduced the Menopause Treatment Tool (MTT) as a resource to support prescribing and patient–clinician dialogue. Gambacciani focused on differentiating MHT options and the role of progestogens. Finally, Stute, on behalf of Panay, presented data on the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) associated with oral combined MHT, drawing on real-world evidence from the USA.

Introduction

MHT is the most effective treatment for the management of vasomotor symptoms and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture.1 Approximately 80% of women experience menopause-related symptoms that affect their daily activities and quality of life.2 Although MHT has proven to be beneficial in relieving these symptoms, only up to a third of women who are symptomatic seek treatment.2 This article discusses the importance of individualising MHT for menopausal women and the potential long-term health effects of this therapy.

A Broad Perspective: Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Potential Long-term Benefits

Antonio Cano

Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Mortality

A serial cross-sectional analysis using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (n=13,048) showed that MHT use among postmenopausal women in the USA declined from 1999–2020 in all age and ethnic groups.3 Cano highlighted that the use of MHT is influenced by perceptions of risk versus benefit, with the low levels of use in recent years mediated, in part, by a fear of side effects of MHT.

Cano referred to the long-term, observational data from two Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) randomised placebo-controlled trials comprising multi-ethnic postmenopausal women in the USA, which showed that there was no significant association between MHT (conjugated equine oestrogens [CEE] plus medroxyprogesterone acetate [MPA] or CEE alone) and all-cause, cardiovascular or cancer mortality during a cumulative follow-up of 18 years.4

Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Osteoporosis Risk

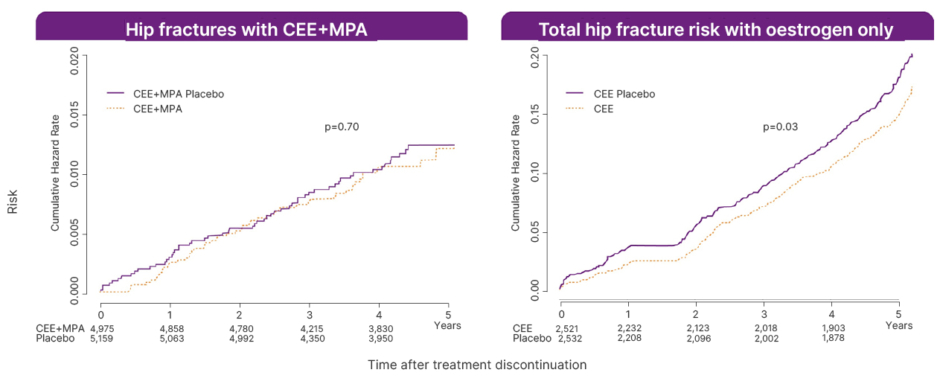

Cano noted that there had been an expectation within the medical community that discontinuing MHT would lead to a rebound loss in bone mass and a corresponding increase in fracture risk, potentially offsetting the preventive effect observed during treatment. However, follow-up data indicate that the reduction in fracture risk may persist beyond cessation of MHT.5 In a WHI follow-up analysis involving 15,187 participants, discontinuation of CEE plus MPA in naturally menopausal women, and CEE alone in those with prior hysterectomy, was not associated with an increased risk of hip fracture during the 5-year post-treatment period (Figure 1).5

Figure 1: Fracture risk up to 5 years postmenopausal hormone therapy discontinuation: analysis of two randomised trials.

Adapted from Watts et al.5

CEE: conjugated equine oestrogen; MPA: medroxyprogesterone acetate.

Cardiovascular Outcomes Following Discontinuation of Menopausal Hormone Therapy

Extended follow-up of the WHI trial, including 7,645 participants, reported that the cumulative risk of coronary heart disease with CEE remained comparable to placebo in the 5-year post-intervention period, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.97 (95% CI: 0.75‒1.25).6 The observed increased risk of stroke and deep vein thrombosis associated with CEE during the intervention phase appeared to lessen following treatment discontinuation.6

An open-label RCT in recently confirmed menopausal women (n=1,006) investigated the long-term effects of oestrogen, with or without progestogen, on cardiovascular outcomes.7 The study included approximately 11 years of randomised treatment, with follow-up extending to 16 years. In this setting, MHT was associated with a statistically significant reduction in mortality, heart failure, and myocardial infarction compared with no MHT (p=0.015), with this difference persisting during the post-intervention period (p=0.020).7 No statistically significant increase in the incidence of cancer, venous thromboembolism (VTE), or stroke was reported during the study.7

Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality with Menopausal Hormone Therapy

Long-term follow-up (up to 22 years) from the WHI trials reported that CEE alone was associated with a lower incidence of breast cancer (HR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.65–0.93; p=0.005) and breast cancer mortality (HR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.37–0.97; p=0.04) compared with placebo (n=10,739).8 In contrast, CEE combined with MPA was associated with a higher incidence of breast cancer (HR: 1.28; 95% CI: 1.13–1.45; p<0.001), with no statistically significant difference in breast cancer mortality (HR: 1.35; 95% CI: 0.94–1.95; p=0.11; n=16,608).8

Further observational data from the French E3N cohort (n=80,377) indicated that breast cancer risk may vary by type of progestogen used and increases with longer duration of exposure.9 Similar associations were observed in a large UK-based study using general practice records, which included 98,611 women with breast cancer and 457,498 matched controls.10

Key Takeaways

Cano highlighted that the risks and benefits of MHT vary according to the type of therapy and route of administration. MHT should be tailored to the individual, considering clinical needs and risk factors. While longer duration of use may be associated with increased breast cancer risk, evidence suggests that the preventive effect against osteoporosis can persist after discontinuation. Cano also noted that public perception of MHT can be influenced by media coverage, underlining the importance of providing clear, balanced information on the long-term risks and potential benefits to support informed decision-making.

Individualised Menopausal Hormone Therapy: Introducing the Menopause Treatment Tool

Petra Stute

The Importance of Individualising Menopausal Hormone Therapy

Stute presented data on a structured approach to support individualised MHT decision-making, highlighting a recently developed clinical tool designed to assist both patients and healthcare providers during the consultation process. Stute explained that during the initial consultation with a woman experiencing menopausal symptoms, the clinician should assess the patient’s individual symptoms, cardiovascular and other risk factors, comorbidities, and treatment goals to support individualised decision-making.

For women with an intact uterus who are eligible for MHT, options include either a fixed oral or transdermal combination of oestrogen and progestogen, or a regimen combining oestrogen (oral or transdermal) with a separate progestogen or intrauterine device.11,12

Stute acknowledged that the management of women through the different stages of menopause is often not easy for clinicians, highlighting international guidelines, such as those from the British Menopause Society (BMS)13 and the European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS),14 as a valuable resource. Stute specified that women with cardiovascular risk factors are recommended to receive a transdermal, rather than an oral, oestrogen product,13,14 and women aged over 60 years should be started on lower doses of MHT, preferably via a transdermal route.15

Unmet Clinical Need in Menopausal Hormone Therapy Prescribing

Despite evidence to support MHT, uptake among menopausal women remains low,16 and current tools for prescribing MHT are impractical in clinical settings or are tailored to specific guidelines.1,15,17-19 Hence, Stute considers there is an unmet clinical need for a globally applicable, user-friendly tool for prescribing MHT. A multi-phase project was launched to develop, validate, and assess the feasibility of a global decision aid tool for diagnosing and treating menopausal symptoms.20

Development and Testing of the Menopause Treatment Tool

Following a literature review, steering committee consultation, and development and pilot test of draft questionnaires, the clinical stage of the project started with an interview phase comprising 48 menopausal women and 18 healthcare professionals (HCP) in six countries. Then, a non-interventional, prospective study was conducted to collect the feedback from 172 MHT-naïve women at a regular check-up, or during a visit to their clinician because of suspected menopausal symptoms, and 49 clinicians (gynaecologists and general practitioners) completing the questionnaires in seven countries (the testing phase).20 Clinician feedback was also gathered through a brief telephone interview. The mean age (range) of the women was 52 (45–60) years, and most of them had conventional menopausal symptoms, such as hot flashes, insomnia, mood irritability, fatigue, or genitourinary symptoms of menopause. After the testing phase, the questionnaires were finalised.

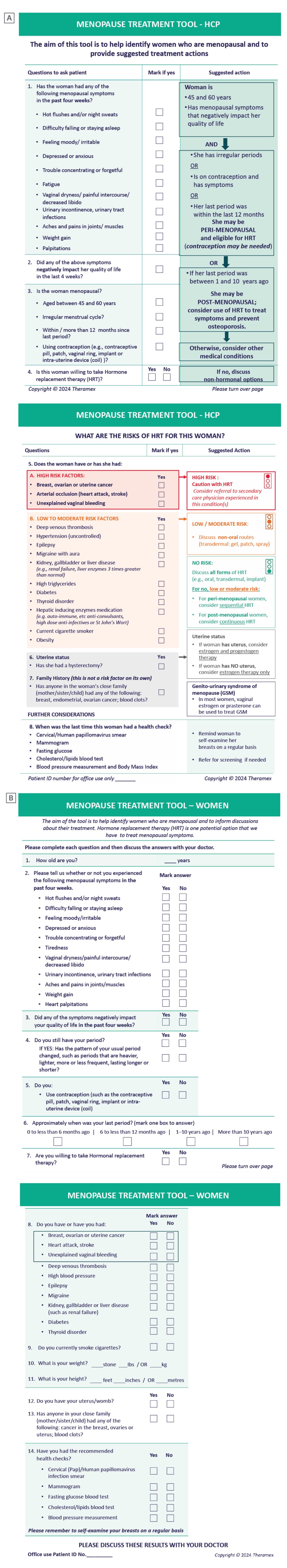

The MTT comprises two questionnaires, one for women (MTT-W) and one for healthcare providers (MTT-HCP), available in six languages.20 The aim of the MTT-HCP is to support the decision-making process, help HCPs identify women who are menopausal, and provide guideline-driven suggested actions (Figure 2A).20 The aim of the MTT-W is to help women identify any menopausal symptoms, and to enhance discussions with their HCPs about treatment (there are no suggested actions in the MTT-W; Figure 2B).20

Figure 2: The Menopause Treatment Tool.

A) MTT for healthcare providers. B) MTT for women.

HCP: healthcare professional; HRT: hormone replacement therapy; MTT: Menopause Treatment Tool.

Feedback on the Menopause Treatment Tool

The majority of HCPs in the study considered the MTT-HCP and MTT-W valid, convenient, easy to use, and worth implementing, and noted that these tools stimulated more interactive discussion during consultations.20 In addition, the HCPs commented that the questionnaires measure and address all relevant questions that arise during a menopause consultation. The MTT-W helped the women in the study to consider symptoms pre-consultation, provided reassurance that their HCPs had relevant details for decision-making, and gave them the confidence to ask relevant questions.20 Finally, HCPs considered the option to overlay the MTT-W with the suggested actions in the MTT-HCP helpful to provide a clear clinical picture and aid discussion during consultation.20

The development and validation of the MTT has been published in an open-access article, and the questionnaires in six languages are available for download in Appendix A of the publication.20

Key Takeaways

Stute concluded that the MTT, comprising both the HCP and patient-facing questionnaires, demonstrated valid content, was feasible for clinical use, and facilitated shared decision-making between healthcare providers and women with menopausal symptoms. The tool was considered useful in identifying menopausal status, supporting guideline-aligned treatment recommendations, and enhancing communication during consultations. Future digital availability may further improve its usability in clinical practice. The evidence presented suggests that the two questionnaires (MTT-W and MTT-HCP) provide valid content, are feasible for clinical use and improve discussion between menopausal women and HCPs.

Differentiation of Menopausal Hormone Therapy: The Role of Progestogens

Marco Gambacciani

The Role of Progestogens in Menopausal Hormone Therapy

Progestogens comprise a heterogeneous group, including micronised progesterone,21 and various synthetic progestins (e.g., norethindrone acetate, and medroxyprogesterone acetate),22,23 and are administered with oestrogen in postmenopausal women.24 Their effects may vary depending on the compound, dose, and route of administration. No direct head-to-head RCTs are available to compare all compounds, and observational findings should be interpreted with caution. The benefits of progestogens include endometrial protection and bleeding control, and these vary with the type, dose, route, and schedule of administration.21,24 Unwanted effects of progestogens (particularly progestins) include somatic symptoms (weight gain, abdominal bloating, increased blood pressure), psychological symptoms (depression, irritability), and unfavourable metabolic effects.21,22 Progestins such as MPA differ from progesterone in that they have androgenic and glucocorticoid effects.22,23

Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Postmenopausal Women

Hormonal changes that occur during menopause are associated with unfavourable metabolic and vascular effects that can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).25,26 Oestrogen replacement can, at least in part, prevent these changes.27 The choice of progestogen used in combination with oestrogen is critical for mitigating CVD risk.1 Androgenic progestins may strongly negate the positive effects of oestrogen.27 Some evidence suggests that certain non-androgenic progestogens may not attenuate some favourable oestrogen effects; data are heterogeneous and not derived from comprehensive direct comparisons across all molecules.27 The use of natural progesterone is associated with lower or no risk for VTE; conversely, synthetic progestins may increase VTE risk through glucocorticoid receptors; therefore, progestins with residual glucocorticoid activity (e.g., MPA) should be avoided.28

Breast Cancer Risk in Postmenopausal Women

The breast cancer risk associated with MHT is influenced by several factors, including treatment duration and the type of progestogen used.9,29 Gambacciani noted that no randomised clinical trials have directly compared the effects of different progestogens on breast cancer risk. However, data from the WHI trial indicated an increased risk with CEE plus MPA (HR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.07–1.46), but not with CEE alone (HR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.62–0.95).30 Observational studies, including the French E3N cohort and a population-based case-control study, indicate that oestradiol combined with micronised progesterone is associated with a lower or neutral risk of breast cancer, whereas combinations with synthetic progestins such as MPA may increase this risk.9,29

Clinical Effects of Progesterone: Improving Sleep and Vasomotor Symptoms

Progesterone is synthesised in the ovaries, adrenals, placenta, and brain, where it is also metabolised. Progesterone receptors have been identified in multiple regions of the brain, supporting its role in central nervous system function.31 Progesterone modulates various brain functions, including neurotransmission,31 core temperature,32 memory, and cognition,33 as well as having neuroprotective actions, such as regenerative capacity,33 myelin repair,34 and dendritic remodelling.35

In addition, progesterone reduces neuronal excitability either directly, or via conversion to allopregnanolone, a naturally occurring neurosteroid that enhances γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA-A) receptor function.36 This enhanced function leads to anxiolytic, antidepressant, neuroprotective, and neurogenic effects (e.g., sleep regulation, and analgesic and anaesthetic effects).21,36

In line with this, low-dose CEE (0.3 mg) plus body-identical progesterone (100 mg) was shown in a short, non-randomised clinical trial to improve sleep to a greater extent than low-dose CEE plus MPA (2.5 mg) or control (calcium–vitamin) in postmenopausal women who are symptomatic.37

Similarly, in the REPLENISH Phase III randomised, double-blind trial, an oral fixed combination of 1 mg oestradiol and 100 mg body-identical progesterone improved sleep disturbances in postmenopausal women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms, with effects sustained for at least 1 year compared to placebo.38

Key Takeaways

Gambacciani emphasised the importance of progestogen selection in MHT, noting that different compounds may vary in their metabolic, cardiovascular, and breast tissue effects. Selected observational analyses reported lower or neutral risks of breast cancer (up to 5 years of treatment) and VTE for some oestradiol plus micronised progesterone combinations compared with certain oestradiol plus specific synthetic progestin combinations (e.g., oestradiol plus MPA). These findings are not generalisable to all oestrogen–progestogen combinations and require confirmation in randomised trials.9,10,29,39 These findings are observational and should be interpreted with caution. Randomised studies indicated that micronised progesterone and progestins are likely equally effective in preventing endometrial hyperplasia/cancer when used at adequate doses39 and, in some studies, improved sleep quality.37,38 The choice of progestogen may therefore influence tolerability outcomes in MHT.29,39,40

Incidence of Major Cardiovascular Events with Oral Combined Menopausal Hormone Therapy: USA Data from Real-World Evidence

Petra Stute, on behalf of Nick Panay

Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events, Real-World Data, and Real-World Evidence

MACEs include acute myocardial infarction, ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, and heart failure, and have a major negative impact on morbidity and mortality in women.41 Real-world data (RWD) are the data relating to patient health status or the delivery of healthcare routinely collected in the clinic setting from a variety of sources (e.g., electronic health records).42 Real-world evidence (RWE) is the clinical evidence about the usage and potential benefits or risks of a medical product derived from analysis of RWD.42 RWD can improve the understanding of health and social care delivery, patient health and experiences, and the effects of interventions on patients and system outcomes in routine clinical settings.43 Stute noted that RWE studies are valuable in terms of resolving gaps in knowledge and driving access to innovations;43 however, these studies have limitations compared with RCTs, including potential for bias, confounding factors, and inconsistent data collection.

Oestrogen–Progestogen Combinations and Cardiovascular Effects

Oestrogens have a beneficial impact on the cardiovascular system, increasing high-density lipoprotein cholesterol,44 improving insulin resistance,45 and reducing atheroma formation;46 however, the addition of androgenic progestogens (e.g., MPA) can negate these cardiovascular benefits.24,47 The use of a non-androgenic progestogen in combination with oestrogen may help reduce or eliminate these unwanted effects.24

Comparing Oestrogen–Progestogen Combinations

There has been no direct comparison between the combination of 17β-oestradiol plus micronised progesterone (E2/P4) and the combination of CEE with MPA (CEE/MPA) regarding the risk of MACE in real-world settings or clinical trials; therefore, an analysis was conducted to provide new insights into these treatment options.48 The goal of the analysis was to compare the effect of a fixed-dose, oral, body-identical combination of E2/P4 with that of non-body-identical combination CEE/MPA on MACE in menopausal women in a real-world setting.

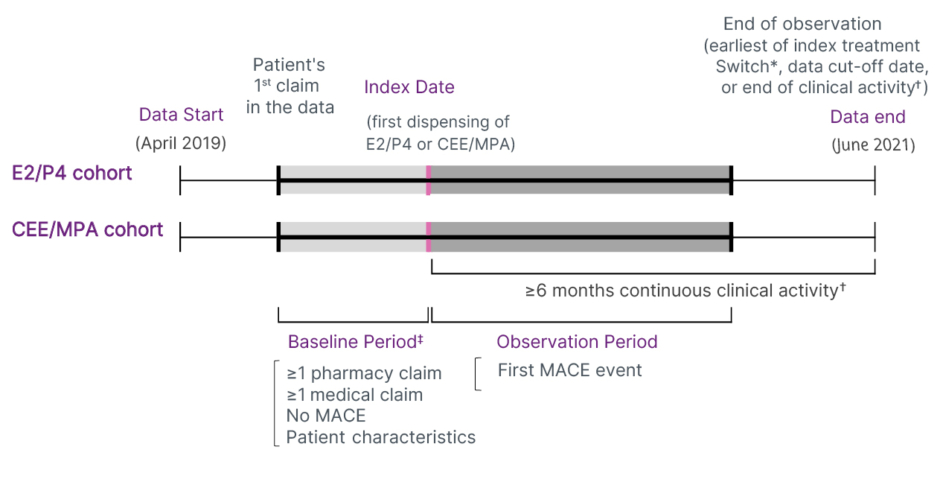

Retrospective Observational Study Methods

This was a retrospective observational study using USA medical insurance claims data from the Symphony Health Solutions Corporation database, which covers over 93% of USA prescriptions and medical claims from 1.9 million practitioners.48 The study population comprised women aged over 40 years receiving their first prescription of E2/P4 (6,520 participants) or CEE/MPA (29,426 participants) who had at least 6 months of treatment (data were collected for up to 2 years after the start of treatment; Figure 3). Study endpoints were hospitalisation for myocardial infarction, stroke, or heart failure. Women with prior MACEs were excluded. Statistical methods were applied to ensure the two treatment groups were statistically comparable.

Figure 3: Design of the retrospective observational study.

Adapted from Stevenson JC et al.48

*Switch from Bijuva® (Theramex, London, UK) (E2/P4) to CEE/MPA, or from CEE/MPA to Bijuva (E2/P4).

✝Pharmacy-based activity was defined as no gap ≥12 months between two prescriptions claims (for HT or other drugs); medical-based activity was defined as no gap ≥12 months between two medical claims.

‡The baseline period, defined as the time from the first claim in the data until the index date, was allowed to vary between patients to maximise the sample size and the capture of covariates. To mitigate the varying baseline period, patients were required to have ≥1 medical claim and ≥1 pharmacy claim in the baseline period and analyses were adjusted for both the time between the first claim and the index date and the year/month of the index date.

CEE: conjugated equine oestrogen; E2: oestradiol; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular event; MPA: medroxyprogesterone acetate; P4: progesterone.

Results of the Retrospective Observational Study

The mean age of participants was similar in the two treatment groups (mid-50s).48 CVD, diabetes, and hypercholesterolaemia were reported in approximately 40%, 11%, and 29% of participants in both groups, respectively. Almost two-thirds of women in both groups were taking medications for anxiety, depression, or sleep disorders.

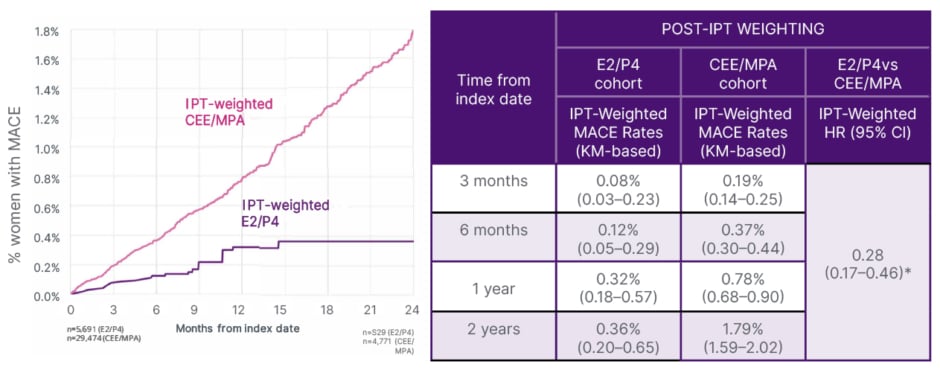

In this exploratory RWE analysis, women who received a prescription for 17β-oestradiol plus micronised progesterone were less likely to have MACEs than those who received CEE plus MPA, with the difference becoming significant after 4 months of treatment (p<0.05; Figure 4); observational design limits causal interpretation.48 The difference between groups in the risk of MACEs was most pronounced for individuals with heart failure, and for those aged 60–69 years (Figure 5).48

Figure 4: Post inverse probability of treatment-weighted analyses of major adverse cardiovascular events in oestradiol/progesterone versus conjugated equine oestrogen with medroxyprogesterone acetate: time to first major adverse cardiovascular event.48

Adapted from Stevenson JC et al.48

*Statistically significant at p<0.05.

IPT-weighted HR was estimated using an IPTW-weighted cox proportional model.

CEE/MPA: conjugated equine oestrogen/medroxyprogesterone acetate; E2/P4: oestradiol/progesterone; HR: hazard ratio; IPT: inverse probability of treatment; IPTW: inverse probability of treatment weighting; KM: Kaplan-Meier; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular event; vs: versus.

Figure 5: Post inverse probability of treatment-weighted analyses of major adverse cardiovascular events in oestradiol/progesterone versus conjugated equine oestrogen with medroxyprogesterone acetate: major adverse cardiovascular event incidence rates.

Adapted from Stevenson JC et al.48

*AR was not reported. AR was calculated separately based on available data.

AR: absolute risk; CEE/MPA: conjugated equine oestrogen/medroxyprogesterone acetate; E2/P4: oestradiol/ progesterone; IPT: inverse probability of treatment; IRR: incidence rate ratio; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular event; WY: women-years.

Limitations of this RWE study include: not all women with MACE might be captured in the database, the percentage of healthy women in the database might be lower than in real life, and data on smoking status, alcohol use, and BMI are missing.

Key Takeaways

Stute concluded that, in this RWE analysis, postmenopausal women treated with a fixed-dose oral combination of 17β-oestradiol and micronised progesterone showed a lower risk of MACEs compared to those receiving CEE and MPA. The difference reached statistical significance after 4 months of treatment.48 These findings are exploratory and require confirmation through further research

Conclusion

This symposium reinforced the importance of individualising MHT and introduced the MTT as a structured support for clinical consultations.20 Presentations also explored how the choice of progestogen can influence treatment considerations, with a focus on the characteristics of body-identical option.

Notes and Limitations

- RWE studies are observational in nature and subject to potential bias and confounding; findings are exploratory and do not establish comparative efficacy or safety.

- Comparisons between different MHT regimens are limited; no direct head-to-head RCTs are available for all progestogens. Observational findings should therefore be interpreted with caution.

- The term ‘body-identical’ refers to the chemical identity of micronised progesterone with endogenous progesterone. This does not imply a therapeutic advantage over other progestogens unless supported by evidence.

Date of Preparation: November 2025

THX_HQ-UK_EN_23407_v2 (v2.3)