To mark World Heart Day 2023, GOLD explores the two sides of the coin in cardiovascular disease. How can the industry strike a balance between driving innovation and ensuring access to care for all?

Words by Jade Williams

In just a matter of days, it will be World Heart Day. Coming up on 29 September 2023, the event is run by the World Heart Federation and aims to improve people’s knowledge of heart health, particularly of the risk factors relating to cardiovascular disease (CVD).

For those working in the cardiology space, their mission is equally simple: to create better lives for people living with heart disease and work towards prevention. Here, CVD is also a core focus, but as it stands, it is the number one cause of death across the globe.

According to WHO, there are 620 million global cases of CVD worldwide, with a whopping 80% of CVD-related deaths occurring in low-and-middle income countries (LMICs). So, in the face of this apparent inequality, does the industry need to take further action?

Well, take action it has. Over the last few decades, innovation in cardiology has skyrocketed – meaning those with CVD are able to live longer and healthier lives. This has, however, caused an interesting paradox: while more people have been able to live longer and survive cardiac experiences, global prevalence has continued to rise along with the death rate.

Unpicking the paradox

While the unbridled pace of pharmaceutical innovation has undoubtedly led to increased life expectancies, this has also given rise to an aging population. New advancements in technology such as monitoring capabilities and medical device implants have resulted in patients living far longer than they previously would have.

“In the past, the diagnosis of cardiovascular disease might have been a death sentence,” comments Jennifer Visser-Rogers, Vice President for Statistical Research and Consultancy, Phastar – a research organisation operating in the pharmaceutical industry. “While people are still dying from the disease, they’re staying alive longer with it.”

The great strides seen in the cardiology space have contributed to this juxtaposition, underscoring the complexity of modern healthcare and the need for ongoing innovation to continue this good work. This is something that analysts predict will continue: the revenue growth for medical devices is forecasted to grow by 52.39% between 2022 and 2028.

In the past, the diagnosis of cardiovascular disease might have been a death sentence

Balancing quality with accessibility

With so much movement in the medical devices space, however, comes the need to ensure all patients have access to high-quality, legitimate devices.

According to Nic Gwatkin, who has led senior leadership positions at both Pfizer and Bayer, “the thing that’s changed dramatically in the past 10 years is the availability of cheap diagnostic equipment”. Blood pressure monitors and the like can be bought from anywhere such as the high street or Amazon. This provides greater access for patients, but also opens the door to the risk of lower quality devices being purchased.

Striking a balance between accessibility and quality is a challenge that the wider pharma sector in Europe, for example, has already sought to address. In 2017, the Medical Device Regulation (MDR) was introduced in the European Union, with the aim of enhancing patient safety and ensuring the quality and effectiveness of medical devices.

Key pillars of the regulation include stricter requirements for medical device manufacturers regarding product safety, clinical evaluation and post-market surveillance. It also introduced a system for assigning Unique Device Identifiers to medical devices to help with traceability.

However, while this legislation was intended to protect patients from poor quality devices, a survey conducted by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in December 2022 found that almost half of the respondents have experienced problems with the availability of medical devices since the introduction of the MDR.

In a press release, ESC said that while it “supports the MDR’s aim to enhance patient safety by improving the standards of clinical evidence required for medical devices”, it also believes that “stronger action is needed to avert this added threat to public health”.

But medical device shortages aren’t just experienced across Europe. This is an issue prevalent in LMICs as well, where the highest proportion of CVD deaths occur, largely because these countries are not as medically mobile.

Bridging the gap in LMICs

The pharma industry goes to great lengths to get heart drugs to countries with less developed healthcare systems, but Gwatkin believes that inequalities could be tackled by making medical devices more accessible in LMICs.

“If you were to put a medical device in a village, social club or barbers,” where there is a high probability of people passing through, “you’d educate a lot of people on their cardiovascular health”, he says. Lack of awareness of medical devices and their potential is huge in areas like Sub-Saharan Africa and more creative strategies like this are needed.

What’s more, despite industry’s best efforts to provide access to medicines, more than 50% of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have no public sector access to CVD medicines. This paints a picture of the steepness of the task, including of the acute need for a greater focus on medical education and prevention within these countries and communities.

The power of prevention

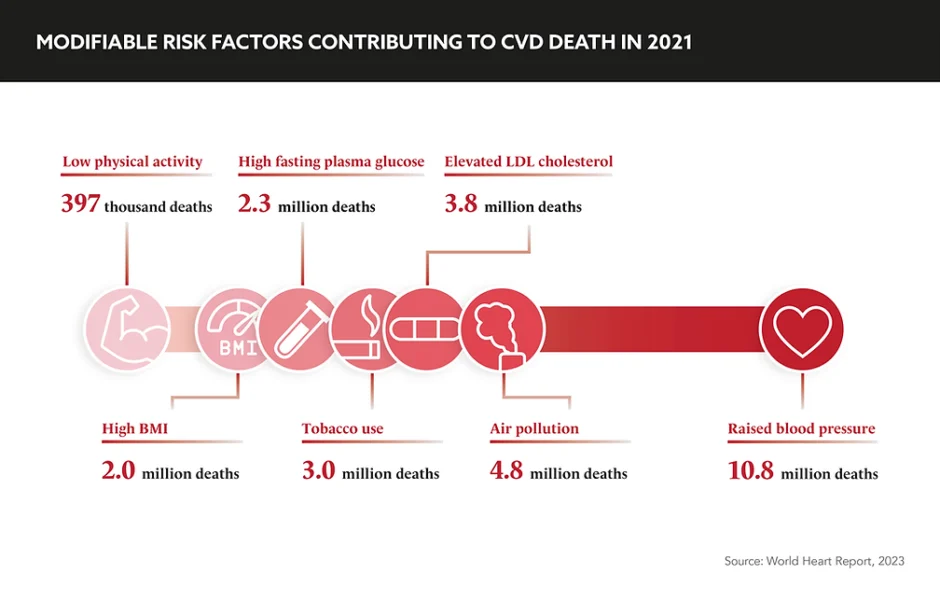

Preventative measures are just as important as treatments – especially so in CVD. Lifestyle modifications, such as a healthy diet, regular exercise and reducing smoking rates, are highly effective means of curbing risk factors for the condition.

“You can actually do something about it. It’s not predestined,” says Barrett Jeffers, Head of Medical Therapeutic Areas Implementation, Viatris, who spoke to his company as part of its ‘Patient Inspiration’ online series about his own experience with heart health and his family’s genetic predisposition to CVD.

Along with monitoring cholesterol levels and eating a heart-healthy diet, he notes that “measuring your blood pressure, for example, is one of the easiest things you can do,” and can greatly improve chances of catching a cardiac event before it occurs.

In addition to lifestyle changes, early detection and intervention have become critical components of reducing the burden of CVD. The burden of these diseases in LMICs can be particularly great, not just on the patient themselves but their family as well.

“In LMICs the ability to work is incredibly important,” elaborates Gwatkin. “If you have a relative who’s had a stroke or is suffering after a cardiac event, this takes a lot out of the family’s labour pool.” Prevention of these events, especially so in countries more driven by manual labour, can prove a beneficial investment economically, socially and culturally.

Thankfully, progress is being made through advances in diagnostic tools and techniques, including non-invasive imaging and genetic testing. These have enabled HCPs to identify individuals at risk for heart disease at earlier stages – allowing for timely interventions and personalised treatment plans, significantly improving patient outcomes.

You can actually do something about it. It’s not predestined

Time to act

As the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases globally continues to grow, it is imperative that the industry takes further action. Around 80% of people with heart and circulatory disease have at least one other health condition, adding to the urgency of the task ahead.

Looking to the future of the field, Visser-Rogers asks companies to consider how “advances in the oncology space, where there is a greater focus on personalised medicine, could trickle down into the cardiovascular space, too”. She also hopes that work will continue on revising clinical trial endpoints, so that they are “more reflective of the true burden of CVD”, rather than focusing on non-specific endpoints such as overall mortality.

As the industry unpicks the paradox of cardiovascular disease, it will undoubtedly discover more and more about the underlying biology of the heart, but it must also reveal innovative methods to empower patients to lead longer, healthier lives. Whether it is through new drugs, medical devices or prevention methods, there isn’t a moment to waste.