Meeting Summary

Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB) is a heterogeneous disease characterised by a ‘vicious vortex’ of pathophysiological processes, with neutrophilic inflammation serving as one of the key drivers. NCFB can lead to exacerbations that significantly impact patients’ quality of life and place a considerable burden on healthcare systems. This year, 2025, Insmed Incorporated presented real-world evidence (RWE) at the American Thoracic Society (ATS) International Conference in San Francisco, California, USA, and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Congress in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The presenters highlighted the unmet needs in global treatment patterns of NCFB, the high hospitalisation burden amongst patients with NCFB on standard of care, and risk factors for exacerbations. The updated ERS Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Adult Bronchiectasis was also published in 2025 for improved diagnosis and proactive treatment of patients with bronchiectasis at high risk for exacerbations.A USA study reported that half of patients with NCFB were managed with medications, including corticosteroids, antibiotics, and β-agonists, within 2 years of their first health insurance claim. Complications, including respiratory failure requiring hospitalisation, were common, suggesting that with current management strategies, patients with bronchiectasis continue to experience exacerbations.

Hospitalisation data from a separate USA study found that, on admission, 85.6% of patients with NCFB had pulmonary exacerbations, 29.5% had respiratory failure, and 39.8% had a respiratory infection. Hospital stays required medications, including antibiotics, bronchodilators, or corticosteroids in a majority of cases. A third of patients required mechanical ventilation and 17% needed intensive care, incurring high healthcare costs and long-term post-discharge care. Hospital readmissions were also common. Data from the UK and French cohorts showed that patients who had experienced ≥2 baseline exacerbations were at a markedly higher risk of exacerbations (160% in the UK; 309% in France), especially those with comorbid COPD, asthma, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), or heart failure. Japanese data revealed that older patients (≥75 years) had higher hospitalisation rates, long-term macrolide use, and exacerbations requiring intravenous (IV) antibiotics.

In 2025, the ERS published updated treatment guidelines for adults with bronchiectasis. The guidelines are recommendations for proactive NCFB management, providing diagnostic algorithms and recommending timely intervention if exacerbation risk is high. Collectively, these advances will inform strategies to reduce exacerbations and alleviate the healthcare burden of bronchiectasis.

Introduction

Bronchiectasis is a chronic and progressive inflammatory lung disease, characterised by permanent and abnormal dilatation of the bronchi and accompanied by cough, sputum production, and recurrent bronchial infection and exacerbations.1,2 Bronchiectasis that is not associated with cystic fibrosis is also known as NCFB.3

NCFB is a heterogeneous disease that is often associated with co-morbidities, including asthma, COPD, and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection, which can make it challenging to diagnose.2,4 The most frequent cause of bronchiectasis is post-infectious, but up to a third of cases are idiopathic.5

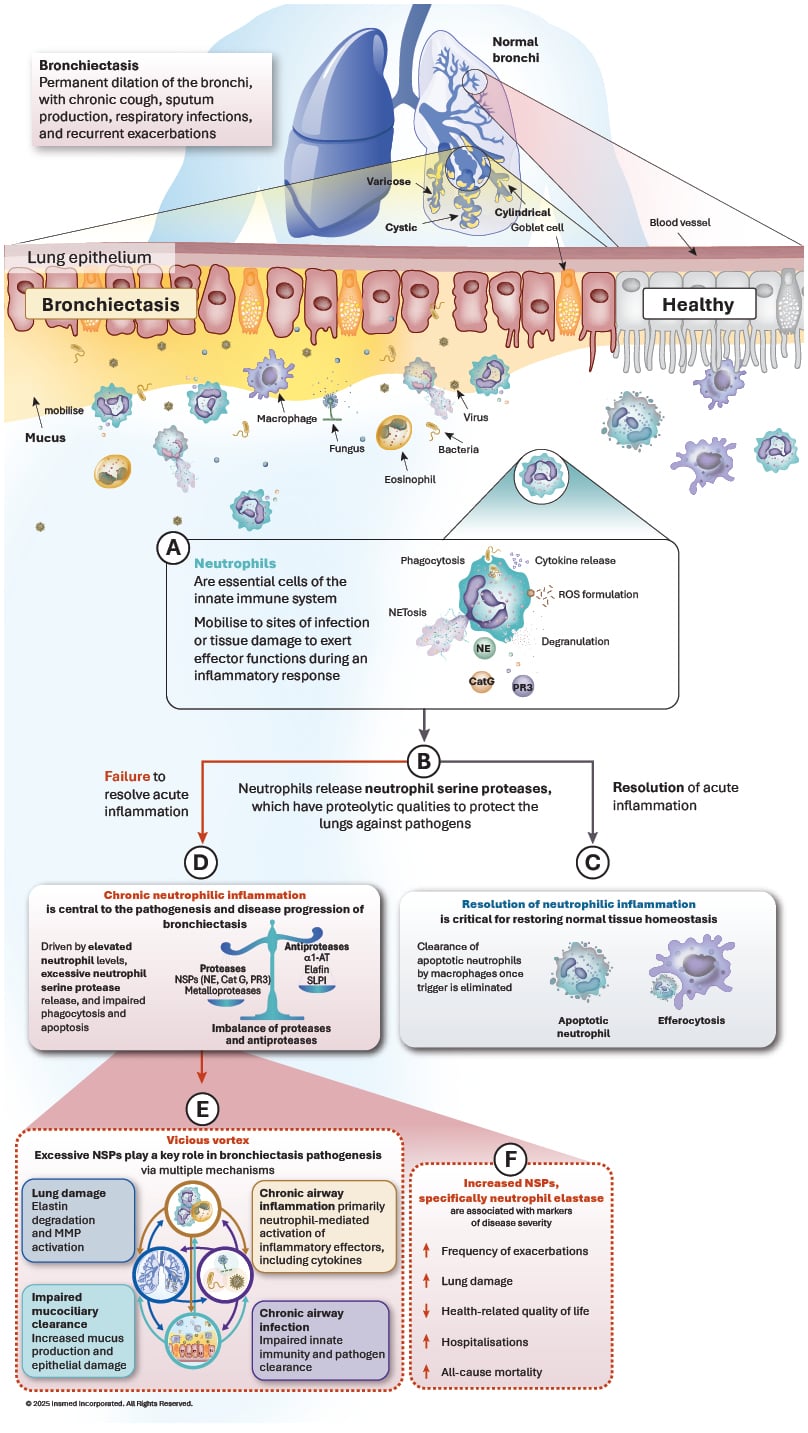

The pathophysiology of bronchiectasis has been described as a vicious vortex, driven by inflammation, chronic airway infection, impaired mucociliary clearance, and structural lung damage.3,6 Neutrophils are important in the pathogenesis of bronchiectasis, and are considered to be one of the key drivers in disease severity and progression.3,6

NCFB is associated with high disease burden on patients and healthcare systems, often presenting with recurrent exacerbations and progressive lung function decline, increased hospitalisations, and worsening health-related quality of life.7,8 Recent retrospective studies of patient registries and insurance claim databases are helping to identify risk factors for exacerbations that will inform better bronchiectasis management strategies.9,10

International ERS guidelines for the management of bronchiectasis, informed by the latest research, recommend a multi-modal approach to management, focusing on controlling symptoms and infection, reducing exacerbations, and enhancing mucociliary clearance.11 However, despite better diagnostic and treatment algorithms to improve bronchiectasis management, there remains a clear and unmet need for specific targeted medications that could help to reduce the patient and healthcare burden of bronchiectasis.

The Vicious Vortex of Inflammation in Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis pathophysiology is a complex mix of self-perpetuating components, referred to as a vicious vortex, that together contribute to progressive lung damage.7,12 There are four key drivers: chronic airway inflammation, recurrent airway infection, impaired mucociliary clearance, and lung damage. Each driver can influence the others, promoting disease progression, permanent bronchial dilation, and further lung function decline.12

At a cellular level, the airways of patients with bronchiectasis are infiltrated by a range of inflammatory cells, primarily neutrophils. However, other inflammatory patterns, including Type 2 eosinophilic, epithelial, or systemic, can also coexist.3,7,12 In response to infection or inflammatory stimuli, neutrophils infiltrate the tissue to exert effector functions such as phagocytosis, cytokine release, and reactive oxygen species production (Figure 1).13 They also release neutrophil serine proteases, which have proteolytic qualities that, in pulmonary infections, help to protect the lungs against pathogens (Figure 1B). However, in bronchiectasis, neutrophil response becomes unresolved, leading to dysregulated chronic inflammation with elevated levels of neutrophil serine proteases (Figure 1C), contributing to structural airway damage and dysfunction (Figure 1D), and driving disease progression, including increased risk of exacerbations (Figure 1E).8,12,14

Figure 1: The role of neutrophils in bronchiectasis pathogenesis.

α1-AT: α1 antitrypsin; Cat G: cathepsin G; MMP: matrix metalloproteinase; NE: neutrophil elastase; NET: neutrophil

extracellular traps; NSP: neutrophil serine protease; PR3: proteinase 3; ROS: reactive oxygen species; SLPI: secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor.

Addressing Challenges of Bronchiectasis Diagnosis

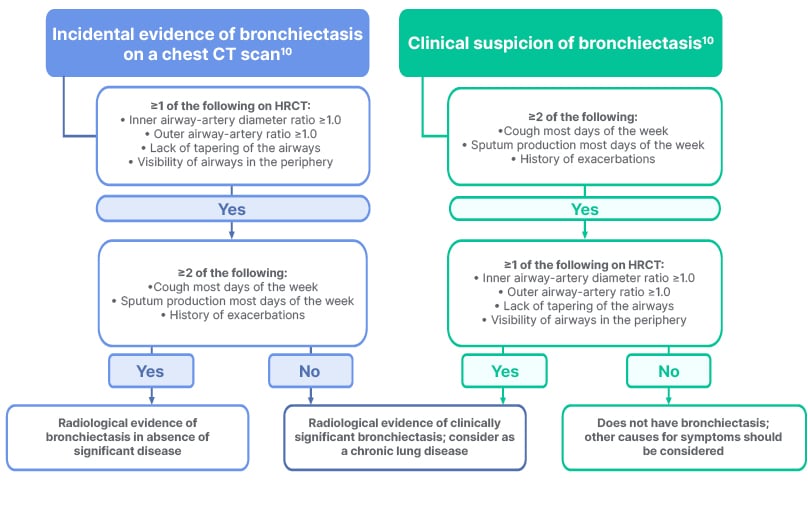

The reported prevalence of bronchiectasis varies between countries, but overall, cases are increasing globally, partly due to more effective diagnosis.15-17 Almost twice as many women as men are affected, and the disease occurs mainly in people over 65 years of age.15-17 NCFB is often initially diagnosed as COPD or asthma,18 but can also present as a co-morbidity alongside COPD, asthma, GORD, and some autoimmune conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis.19,20 Delayed diagnosis is common, particularly in women,4 and the time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis can be over a decade.4 Accurate diagnosis of clinically significant bronchiectasis requires both clinical symptoms, such as cough or sputum production, and radiological findings (Figure 2),21 with a chest CT scan forming an integral part of the diagnostic algorithm.19,21 Diagnostic features include dilation of the bronchial wall such that the internal lumen diameter exceeds that of the accompanying pulmonary artery, and lack of tapering and visibility of airways in the periphery. Other clinically relevant radiological features include bronchial wall thickening and mucus plugging, as well as centrilobular nodules in a ‘tree-in-bud’ pattern.19

Figure 2: Diagnosis of clinically significant bronchiectasis requires both clinical and radiological criteria.19,21

HRCT: high-resolution CT.

Real-World Data Provide Novel Insights

Currently, the primary management goals of bronchiectasis focus on symptom control and reducing exacerbation frequency to improve health-related quality of life.11 However, the clinical heterogeneity of the condition and limited treatment options available create challenges for clinicians and patients alike. Real-world data on clinical outcomes and treatment patterns for NCFB are providing novel insights that will enhance understanding of bronchiectasis management practices and help to identify more effective approaches. During 2025, several retrospective studies of bronchiectasis patient data were presented at international conferences, including ATS 2025 and ERS 2025,22,23 providing new data on treatment patterns, complications, and hospitalisations.

Exacerbation Risk Factors

An exacerbation in bronchiectasis is defined as a person with bronchiectasis experiencing deterioration in three or more key symptoms for at least 48 hours, combined with a clinician’s determination that a change in bronchiectasis treatment is required. Core symptoms of exacerbation include a change in cough, sputum volume and/or consistency, sputum purulence, dyspnoea and/or exercise intolerance, fatigue or malaise, and haemoptysis.2 Additional clinical features can indicate a severe exacerbation requiring hospitalisation or IV antibiotic treatment.11

Approximately half of patients with bronchiectasis experience at least two exacerbations per year, and these have a significant impact on patient quality of life, clinical outcomes, and healthcare resources.24

Morbidity and Exacerbations in Patients with Non-cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis in the UK and France

Two retrospective studies that explored patient data from The Health Improvement Network (THIN®, London, UK) UK and France databases23 defined exacerbations as primary care physician visits with codes for exacerbations, haemoptysis, lower respiratory tract infection, or antibiotic prescription with either bronchiectasis or ≥1 lower respiratory tract infection symptom.23 A total of 12,106 patients were included in the UK study and 6,194 in the France study, of whom 15.5% and 12.5%, respectively, experienced ≥2 exacerbations during the baseline period based on this database. Data analysis revealed that patients experiencing ≥2 exacerbations during the baseline period were significantly more likely to have comorbidities such as asthma, COPD, GORD, and heart failure compared to those with <2 exacerbations.23

Approximately 70% of patients in the UK and 75% of patients in France with ≥2 exacerbations during the baseline period experienced a subsequent exacerbation within the first year of follow-up. In contrast, in patients who had <2 exacerbations during baseline, 30% and 25% of patients in the UK and France cohorts had a subsequent exacerbation during the follow-up period. Further analysis of the data determined that having ≥2 exacerbations in the baseline period correlated with a 160% increased risk of further exacerbations during follow-up in the UK and a 309% increased risk in France.23 In the UK cohort, comorbid COPD was associated with a 48% increased risk of further exacerbations, while asthma increased the risk by 21%. In the French cohort, COPD and heart failure also increased the risk of further exacerbations by 27% and 21%, respectively. 23

These data reveal that patients with bronchiectasis who had ≥2 exacerbations during the baseline period were at the highest risk of experiencing exacerbations during follow-up. In addition, patients with ≥2 exacerbations during baseline had more comorbidities, including asthma in the UK and COPD in both countries, and a higher overall treatment burden than those with <2 exacerbations.23 Overall, these data illustrate the importance of effective strategies aimed at reducing and managing exacerbations as a means of alleviating the overall burden of bronchiectasis.

Exacerbations Among Incident Cases of Non-cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis in Japan

In Japan, a retrospective analysis of two insurance claims databases provided by JMDC, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) included individuals aged <75 years from February 2015–April 2023 and aged ≥75 years from April 2019–March 2023. Patients with bronchiectasis were identified according to claims-based diagnostic criteria and defined as meeting bronchiectasis diagnosis criteria (index date) and without any other bronchiectasis-related claim in the year before the index date.23,25

A total of 6,288 patients aged <75 years and 1,127 patients aged ≥75 years identified as incident cases of bronchiectasis were included in the analysis. Compared with those aged <75 years, a higher proportion of patients aged ≥75 years had all-cause hospitalisations, respiratory-related hospitalisations, and long-term macrolide use during the 1-year period before the diagnosis of NCFB. Overall, 63.6% of patients aged <75 years (mean follow-up duration of 2.8 years) and 67.2% of patients aged ≥75 years (mean follow-up of 1.4 years) experienced at least one exacerbation during the follow-up period.23,25

The proportion of patients who required hospitalisation or IV antibiotics for an exacerbation was approximately three-times higher in the ≥75-year group compared to that in the <75-year group (67.6% versus 23.0%, respectively). Similarly, the annualised rate of exacerbations requiring hospitalisation or IV antibiotics was around six-times higher among patients aged ≥75 years than among those aged <75 years (0.43 versus 0.07 per person-year, respectively). The study also concluded that patients with comorbidities, including COPD, asthma, non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection, or chronic rhinitis, presented in higher proportions with exacerbations.23

The findings demonstrate a substantial burden of exacerbations, evident irrespective of age or the presence of pre-existing respiratory diseases. These results underscore the unmet need for effective management strategies aimed at reducing or preventing exacerbations.22,23,25-29

Treatment Patterns

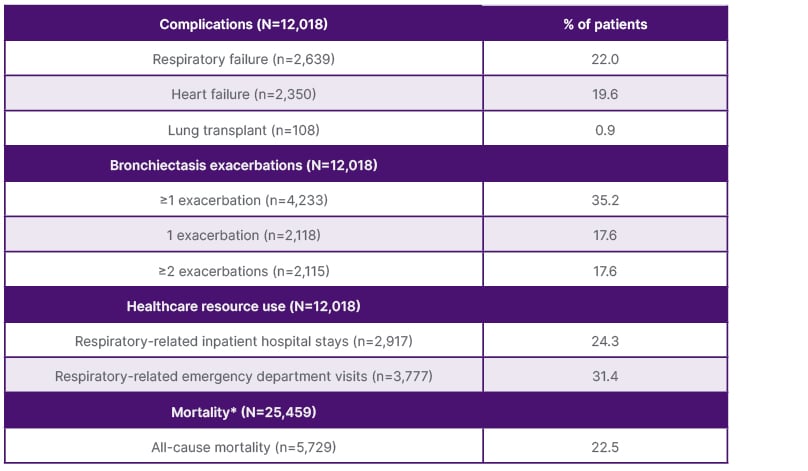

Data from a retrospective cohort study using de-identified claims from the Optum® Market Clarity database (Optum, Eden Prairie, Minnesota, USA)26 provided new evidence on treatment patterns and complications in NCFB. The study included patients diagnosed with NCFB in the USA between 1st January 2017–31st March 2020.26 Eligible patients were those aged ≥12 years who had made more than two outpatient claims more than a month apart, or one inpatient claim with a bronchiectasis diagnosis code. The analysis identified 12,018 people with NCFB (mean age: 68.5±13.2 years; 67.0% female).26 During the 2-year follow-up period, commonly prescribed medications included corticosteroids, short-acting β-agonists, antibiotics, and long-acting β-agonists, with around half of patients receiving one or more medications during the follow-up period. The study also reported on complications that included respiratory failure (22.0%), heart failure (19.6%), having a lung transplant, and experiencing one or more bronchiectasis exacerbations (Table 1).22

Table 1: Complications and all-cause mortality during follow-up.17

*Continuous enrollment or clinical activity were not required during follow-up.

Additional real-world data on treatment patterns come from retrospective analyses of patient cohorts from the THIN® UK and France databases.27,28 The studies demonstrated that patients who experienced ≥2 exacerbations during baseline were more likely to have received medications such as antibiotics (oral and inhaled), inhaled corticosteroids, oral steroids, mucolytics, and bronchodilators, either at baseline or during follow-up, compared to those with fewer than two exacerbations. In the UK, the use of long-term antibiotics remained consistent between 2018–2022 among patients with ≥2 exacerbations during baseline, with approximately one in four patients receiving these therapies (23.8% and 24.5%, respectively).23 In France, antibiotic prescriptions declined over time in patients with ≥2 exacerbations, from 91.9% of patients in 2018 to 80.4% in 2022. However, the use of long-term antibiotics remained relatively stable across the same period (15.5% and 13.5% in 2018 and 2022, respectively).23 These data demonstrate the complexity of treating NCFB due to heterogeneity. Frequent switching of antibiotics, reliance on multiple symptom-based therapies and steroids, along with ongoing exacerbations, suggest current approaches often fall short of effectively managing bronchiectasis and preventing complications.22

Hospitalisations and Implications for Healthcare Costs

A separate retrospective study investigated patient data recorded in the USA Premier Healthcare database (Premier Inc., Charlotte, North Carolina, USA), with 73,656 patients identified aged ≥12 years (mean [SD] age: 71.8±14.7 years; 58.3% female), hospitalised between 1st January 2018–30th June 2022, with a primary or secondary diagnosis of bronchiectasis. For analysis, patients with a primary diagnosis of COPD, asthma, or cystic fibrosis were excluded.29

At index hospitalisation, 39.8% of patients had an existing respiratory infection, 29.5% had respiratory failure, and 85.6% had a pulmonary exacerbation.29 Length of hospital stay varied (7.1±9.4 days), and the most common treatments during hospitalisations were antibiotics (83.9%), bronchodilators (76.8%), and corticosteroids (68.6%).29 Additionally, 34.6% of patients required mechanical ventilation.29 Approximately 17% required intensive care, costing 16,375±35,847 USD. Following the index hospitalisation, 5.9% of patients died.29

The study also found that, post-discharge, most patients had significant post-acute care needs, with over half (53.8%) requiring specialised care plans; 23.3% were discharged to specialised healthcare facilities for long-term, around-the-clock care, and 21.9% received home healthcare.29 Patients were also likely to be readmitted to hospital, resulting in higher healthcare costs; 22.6% were readmitted within 90 days of discharge, for on average 7.9±9.6 days, costing 24,576±41,189 USD.29

Updated Bronchiectasis Guidelines Set New Standards for Bronchiectasis Management

Since the first international guidelines for bronchiectasis were published by the ERS in 2017,30 there has been a notable increase in clinical trials and research activity in bronchiectasis, including extensive data from patient registries.9,10 Updated guidelines, published in 2025,11 recommend a more holistic approach to patient care.

As recommended in the ERS Guidelines,11 all newly diagnosed patients should be assessed for known comorbid illnesses, including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, depression, rhinosinusitis, and GORD. Importantly, all newly diagnosed patients should have a Bronchiectasis Severity Index (BSI) calculated to assess the risk of future complications and mortality.11

Recommended treatments focus on airway clearance with muco-active agents to reduce symptom burden and improve quality of life. Long-term antibiotic use requires antimicrobial stewardship, including a treatment algorithm to support best practice. Patients at high risk of exacerbations include patients with a history of two or more exacerbations in the prior year, or one severe exacerbation, or one exacerbation plus severe daily symptoms. Long-term macrolides are recommended for patients at high risk of exacerbations, including patients with chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, patients with airway infection caused by other pathogens, and those without evidence of airway infection, but should not be prescribed as monotherapy for NTM.11 The ERS guidelines make it clear that a more proactive patient-centred approach to treatment is needed, based on identifying patients with high disease activity (frequency, severity, and impact on quality of life of symptoms and exacerbations), and therefore at high risk of progression, to help prevent further deterioration.11

Conclusion

Current management of bronchiectasis is still suboptimal, based on RWE that shows patients still experience exacerbations. Increased awareness of early diagnosis of bronchiectasis can lead to earlier management strategies and potentially a decrease in exacerbations. Studies have identified risk factors for exacerbations, including comorbidities, recent history of exacerbation, and age.

RWE from retrospective studies highlights that exacerbations and complications as a result of bronchiectasis are contributing to high hospital readmission rates and direct medical costs, and negatively impacting patient quality of life. New treatment guidelines emphasise the need for a more proactive and patient-centred approach to bronchiectasis management and treatment.