Abstract

Periorbital necrotising fasciitis (PNF) is a devastating and rare infection of the subcutaneous soft tissues with necrosis of the superficial fascia. PNF can cause vision loss, disfigurement and, if left untreated, can lead to multi-organ failure, shock, and eventually death. There is no definite protocol to manage PNF, but it is universally accepted that the treatment should consist of broad-spectrum antibiotics and surgical debridement of the affected tissue. The authors present the case of a 68-year-old man who arrived at the emergency department with severe pain, swelling, and eschar in the left eye. He also reported neck and lower-jaw pain with restricted movement, difficulty swallowing, and complete loss of vision in the left eye. These symptoms developed 2 days after he sustained a facial injury from a fall on his bathroom floor. Necrotising fasciitis started to develop after a few days, and he was diagnosed with streptococcal PNF. The patient thus required multiple surgical debridements, along with a course of broad-spectrum antibiotics. This case highlights the importance of early detection of PNF. Rapid detection and a coordinated multidisciplinary approach can be crucial in saving patients’ lives. Patients with redness, swelling, and pain in the periorbital area that developed after a trauma, even if minor, must seek medical attention to avoid serious complications.

Key Points

1. Periorbital necrotising fasciitis (PNF) is a rare but rapidly expanding infection with significant morbidity, and mortality reaching 10–15% of cases. This case highlights unusually extensive PNF without prior risk factors, stressing the need for immediate recognition and intervention.2. In this case report, the authors detail a unilateral streptococcal PNF extending from the orbit to the chest; repeated surgical debridement and targeted antibiotics were required due to rapid necrosis and recurrent tissue involvement.

3. Early diagnosis, aggressive antimicrobial therapy, and prompt multidisciplinary surgery are critical to survival in periorbital necrotising fasciitis. Timely management can prevent systemic complications and unnecessary enucleation, even in advanced presentations.

INTRODUCTION

Periorbital necrotising fasciitis (PNF) or streptococcal gangrene is a rare infection that affects the periorbital region, the surrounding fascia, and the underlying subcutaneous tissue.1,2 This soft-tissue infection can cause extensive damage and necrosis of the underlying tissue, resulting in gangrenous effects and secondarily affecting the overlying skin. β-haemolytic Streptococcus is responsible for a large number of PNF cases, averaging about 50%, with 18% of these cases being superimposed with a Staphylococcus aureus infection.3

Periocular involvement in necrotising fasciitis is quite uncommon and can result in facial disfigurement, ocular problems and, in some cases, death. Elner et al.4 stated that the mortality rate resulting from PNF averaged around 10–15%, and was linked to shock and septicaemia.4,5 This mortality rate is lower in comparison to necrotising fasciitis occurring in other locations in the body. Early diagnosis and management of this condition, both medical and/or surgical, is essential for the survival of the patient and the reduction of systemic complications.6

This case is unique due to the unilateral involvement of the periorbital region rapidly extending to the neck and chest without any risk factors such as diabetes or immunosuppression. Despite the severity of the disease and the multiple surgeries performed, the patient survived without enucleation, which is rare in such advanced cases.

CASE PRESENTATION

Patient Information and Clinical Findings

A 68-year-old man was brought to the Emergency Medicine Department of the Caucasus Medical Center, Tbilisi, Georgia, by an emergency brigade. According to the patient, he sustained a facial injury 2 days prior and did not seek medical attention. Within hours of the injury, he developed swelling on the left side of his face, tearing from the left eye, and swelling of the left periorbital and cheek area, along with a temperature of 38 °C and severe pain. The patient had no history of chronic diseases, allergies, or current medications. Upon admission, he complained of severe pain and swelling in the left eye, cheek, and lower jaw. He also experienced restricted movement of the neck and lower jaw, difficulty swallowing, and loss of vision in the left eye.

Clinically, the patient presented with asymmetry in his face because of the swelling in the periorbital region, the left chewing jaw area, the left half of the upper lip, and the left lower jaw. Swelling extended to the left temporal forehead and the left side of the neck. The skin appeared reddened and stretched, and palpation revealed fluctuation, particularly beneath the cheek and jaw. A 5 mm diameter eschar was observed on the lower eyelid of the left eye (Figure 1). Notably, the patient had completely lost vision in his left eye.

Figure 1: Pre-operative clinical presentation.

Subcutaneous lymph nodes under the jaw were enlarged, and the patient also exhibited right cheek swelling, along with transient wrinkles in both upper jaws. The mouth appeared swollen, stiffened, and hyperaemic.

Diagnostic Assessment and Initial Management

The preliminary diagnosis for the patient was a facial, neck, forehead, and parietal-occipital phlegmon. Empiric intravenous (IV) antibiotics were initiated immediately upon admission: ceftriaxone 2 g every 12 hours, clindamycin 600 mg every 8 hours, and metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours.

CT of the head, face, and neck revealed primarily on the left side, extending caudally from the convexity of the forehead, ventrally forming, viscous, non-contoured masses. Swelling of fatty tissue at the same level of trapezoidal muscle and scapula was also seen. Both sinuses were filled with viscous masses.

Orbital CT showed proptosis, obliteration of periorbital fat planes, and opacification in the extraconal space, consistent with orbital cellulitis. Optic nerve sheath enhancement was noted, suggesting possible ischaemic optic neuropathy, correlating with the clinical vision loss. There was no intracranial extension or cavernous sinus involvement.

Therapeutic Intervention

Performed by maxillofacial surgeons, 2 cm below the lower edge of the lower jaw, an incision was made in the skin and subcutaneous soft tissues, extending the wound towards the left cheek and the area of superficial muscle dissection. Approximately 50 mL of inflamed, yellowish, viscous fluid was collected. Bilateral antrostomy was performed, yielding 30 mL of inflamed exudate. General surgeons drained exudate from incisions along the trapezius and chest. Multiple incisions were connected with drainage.

On Day 2 of admission, the patient was transferred to the critical care unit. The patient’s condition was severe, requiring vasopressor and inotropic support. The following day, necrosis signs appeared on the left eyelid and temporal skin.

The patient underwent daily wound care and antiseptic washing. On Day 12 of admission, necrotic tissues and eye muscles were removed (Figure 2). Haemodynamics improved postoperatively, though necrotic fasciitis reappeared in the left cheek and chewing area by Day 15. Further surgery on Day 20 involved extensive necrotomy and curettage of facial tissues.

Figure 2: Necrotising fasciitis spread to the left cheek and chewing area.

Microbiological Findings

Bacteriological analysis confirmed Streptococcus pyogenes, EMM Type 1. Antibiogram showed it was sensitive to penicillin, clindamycin, vancomycin, and linezolid. Blood cultures were negative, most likely due to the empiric antibiotic treatment started before taking the cultures.

Antibiotic Treatment

After microbiology confirmed the presence of Streptococcus pyogenes, treatment with antibiotics was narrowed to penicillin G 4 million IU IV every 4 hours with clindamycin 600mg every 8 hours; metronidazole and ceftriaxone were discontinued. The total IV course lasted 21 days, followed by amoxicillin-clavulanate 1 g orally every 12 hours for 7 days after discharge from the hospital.

Follow-up and Outcomes

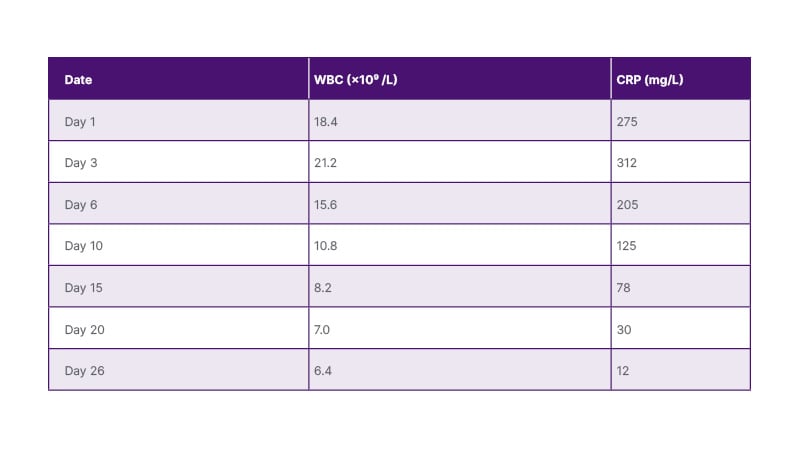

Inflammatory markers (Table 1) showed improvement with treatment. Granulation tissue developed. Despite vision loss, enucleation was not needed. Skin recovered, and facial movements improved (Figure 3).

Table 1: Longitudinal laboratory markers.

CRP: C-reactive protein; WBC: white blood cells.

Figure 3: Complete recovery of the patient’s facial skin.

DISCUSSION

This case, in Georgian medical practice, represents a rare case of Streptococcal PNF characterised by the rapid spread of surgical necrotic infection and a high risk of mortality. PNF is mostly caused by Gram-positive A β-haemolytic Streptococcus, but other bacteria, such as Pseudomonas, and other organisms like fungal (Cryptococcus, Aspergillus) or viral (chicken pox, herpes zoster) pathogens have also been reported as causative agents.7 The incidence of necrotising fasciitis is estimated to be about 3.5 cases per 100,000 individuals, with a mortality rate ranging from 10–40%, which can rise to up to 80% without medical and surgical intervention.8

Necrotising fasciitis more frequently affects the lower abdomen, the groin, and the lower limbs. The head and neck and periorbital area are rarely affected due to their abundant blood supply.3 In fact, necrotising fasciitis displays unique characteristics compared to its manifestation in other areas of the body. The skin in the eyelids is thin, with no subcutaneous tissue, and an abundant blood supply. This abundant blood supply acts as a barrier between the skin and the periorbita, which helps in preventing infection. However, when infections happen, necrosis appears rapidly, thus allowing an early recognition of the infection. In addition, the spread of infection is somewhat prevented by the firm attachment of the dermis to the nasojugal fold medially and the malar fold laterally. But once this barrier is broken, the infection spreads to the neck, as in the authors’ case. The area over the nasal bridge from one eyelid to the other is the path of least resistance, making the bilateral periorbital infections more frequent than unilateral.5

It has been reported that the risk factors for developing necrotising fasciitis include a variety of immunosuppressive conditions like diabetes, chronic renal failure, vascular disorders, active smoking, alcoholism, systemic malignancy, and the use of immunomodulating drugs such as steroids or chemotherapy. When the patient’s age is higher than 50 years, this has been shown to increase the risk of death from the infection.5 PNF can develop in people of all ages, sexes, or races, and the most reported causative agents can be penetrating injuries, lacerations, abrasions, insect bites, or hypodermic needle injections.9 Sometimes, the injury can be too insignificant for the patient to notice.7

In most cases of PNF, early symptoms will show significant skin changes that indicate severe inflammation, like colour change, hyperaemia, and vesicle formation. When there’s worsening pain, oedema, and crepitus, it signifies a serious subcutaneous necrosis and vascular compromise.10 It is crucial to differentiate PNF from other similar conditions like Wegener’s granulomatosis, erysipelas, cellulitis, and phlegmon. Acute fulminant skin disorders like pyoderma gangrenosum, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and rhino-orbital mucor mycosis must be excluded.11 PNF can have terrible outcomes like necrosis of orbital muscles, severe disfigurement, and eye loss, and the complications can range from blindness to meningitis and other neurological disorders, to death.3 Death is usually the result of a delayed diagnosis or no intervention that leads to septicaemia, systemic shock, and multi-organ failure.

The authors’ patient received aggressive antibiotic treatment as well as surgical debridement, which are both necessary in the management of necrotising fasciitis. However, despite that treatment, complications still arose, and their patient still needed multiple surgical interventions due to the rapid spread of the necrosis. According to a review by Sarani B et al.,12 multiple surgical interventions are almost always needed because a single surgery can rarely be enough to eradicate the infection. Usually, antibiotics alone are not enough to treat NF, especially if the management is delayed, because antibiotics do not reach the effective concentration in the necrotic tissues.12 So, surgical debridement would be required to get better results. Hyperbaric oxygenation and IV gamma globulins have also been suggested in specifically severe instances.13 However, multiple studies have reported cases where antibiotic treatments alone were enough and surgery was not needed,14,15 emphasising the importance of early diagnosis and intervention.

Though initially misdiagnosed as a phlegmon, the authors’ patient experienced a favourable outcome of his PNF. Rhino-orbital zygomycosis was also considered as a differential diagnosis due to the rapid progression and orbital involvement. Zygomycosis, also known as mucormycosis, is a highly invasive fungal infection. It affects the lungs, sinuses, skin, gastrointestinal tract, and the craniofacial region, including the orbit. Early identification and management are crucial to avoid devastating complications.16 Cutaneous zygomycosis can result from a skin trauma leading to the invasion of the muscles and bones, such as in the authors’ case. However, zygomycetes cause infections almost always in immunocompromised patients, which is not the case with the authors’ patient. In addition, mycological tests were negative, and no black necrotic eschars were seen. Moreover, Streptococcus pyogenes was confirmed via culture, aligning more with bacterial necrotising fasciitis.

The rapid evolution of the infection and necrosis allowed the rule out of other differential diagnoses, and ultimately resulted in a multidisciplinary approach with aggressive antibiotics and repeated surgical debridement, which eventually led to saving the patient’s life.

The surgical debridement usually serves to limit the spread of the infection to the neighbouring healthy tissues, and thus enables us to preserve the maximum amount of tissues, and facilitate local healing.17 The authors’ patient presented to the clinic when vision loss had already started, so saving the sight in his left eye was not possible; however, there was no necessity to remove the left eyeball despite the severity of the infection because of the growth of granulation tissue over the necrotic area.

Due to the severity of the disease and the involvement of various anatomical structures, a multidisciplinary approach is always necessary when managing such a condition. The majority of cases require maxillofacial surgeons, plastic surgeons, ophthalmologists, and sometimes it might require the presence of a psychiatrist, because it could be a traumatising injury that requires giving the patient support.8

Finally, this case highlights the critical need for early recognition and aggressive intervention in managing necrotising fasciitis, particularly in cases involving facial injuries. The rapid progression and severity that was observed emphasise the importance of timely surgical procedures, including incision, drainage, and necrotomy. Uncommon complications, such as complete loss of vision, underscore the necessity for vigilant monitoring and thorough microbiological examination for an appropriate antimicrobial therapy. The recurrence of necrotising fasciitis in spite of initial surgical intervention stresses the challenges in completely containing the infection.

CONCLUSION

This case highlights the significance of imaging, thorough investigation of the tissue, and standard debridement of necrotic tissue. PNF, although rare, can have devastating outcomes and must be included in the differentials of a rapidly spreading inflammation in the periorbital area, because early detection and management can have satisfying results. Recommendations include advocating for multidisciplinary collaboration, considering potential visual impairment in treatment plans, and promoting patient education on warning signs. These insights aim to enhance clinical practice, emphasising regular follow-up and surveillance to address complications and improve outcomes in facial necrotising fasciitis cases.

Patient Perspective

Reflecting on his journey, the patient recalls the horrific experience that led him to the emergency department at the Caucasus Medical Centre. Initially dismissing his symptoms, he was soon faced with excruciating pain and alarming symptoms that signalled a grave underlying condition.

The patient attributes his condition to the occupational hazards inherent in farming. His loss of vision has significantly impacted his life. However, despite these challenges, he expresses satisfaction with the treatment received and commends the medical team for their exceptional care.