Abstract

Background: Attention deficits represent one of the most prevalent cognitive impairments following acquired brain damage. Given its important role in supporting a wide range of everyday and occupational activities, attention is considered one of the key domains of cognitive functioning. This study investigates pre-post changes in attentional performance during computer-based cognitive training (CCT) in the context of neurological rehabilitation.

Methods: In this retrospective, observational study, data from 127 patients undergoing CCT during neurological rehabilitation were analysed. The training targeted impaired attentional components, which were assessed before and after the intervention using the Test of Attentional Performance (TAP). Specific analyses focused on alertness, selective attention, and divided attention.

Results: Significant pre-post improvements in alertness, selective attention, and divided attention occurred during CCT participation, irrespective of primary diagnosis or training duration. Both the CogniPlus training tasks (Schuhfried, Mödling, Austria) and the independent TAP assessment reflected training-related changes. However, a subgroup with more severe baseline impairments showed less pronounced training-related changes.

Conclusion: Participation in CCT was associated with significant improvements in attentional functions. Although these findings are clinically encouraging, they should be interpreted as descriptive pre-post changes rather than as evidence of causal treatment efficacy. Prospective, controlled studies are necessary to determine the long-term effects of CCT and to evaluate its impact on functional outcomes in everyday life.

Key Points

1. Participation in computer-based cognitive training was associated with improvements across multiple attentional domains, including alertness, selective attention, and divided attention, with training gains evident across different indications and disease durations. However, patients with more severe baseline impairments tended to show reduced responsiveness.2. Training-associated gains extended beyond task-specific training performance, as reflected by improved outcomes on an independent neuropsychological assessment, indicating consistent improvements within the same attentional domains targeted during training. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating training-associated cognitive improvements following acquired brain injury.

3. Despite the promising pre-post changes, the impact of computer-based cognitive training on everyday functioning and quality of life remains unclear. Moreover, the cognitive and motivational demands of the training may restrict its applicability to patients with relatively preserved cognitive capacities and high motivation, potentially limiting generalisability.

INTRODUCTION

Cognitive impairments are highly prevalent and functionally significant consequences of acquired brain injuries, including stroke1 and traumatic brain injury.2 These impairments may involve multiple cognitive domains, such as attention, memory, language, and executive functions.3 Post-stroke cognitive impairments, for example, occur in 30–57% of patients within 6 months4 and significantly affect quality of life.5 They are also associated with increased mortality and institutionalisation rates,6 as well as elevated healthcare costs.7

Among cognitive domains, attention plays a crucial role in everyday functioning.8 It can be defined as the ability to detect, select, and respond to the multitude of stimuli present in our environment.9 Attentional deficits represent the most frequently observed cognitive impairment following brain injury, with incidence rates after stroke ranging from 46–92%.10 Although some patients recover from attentional impairments over time,11 approximately 20–50% of survivors of stroke continue to experience persistent attentional deficits for years after the event.12-14 As a fundamental basis of higher-order cognitive processes, attention supports memory, language, and executive functions, and deficits can negatively affect these domains.15 Clinically, they manifest as reduced concentration, increased distractibility, poor error monitoring, diminished multitasking ability, slower information processing, and mental fatigue. These deficits can negatively influence functional outcomes,16 limiting participation in other critical areas of rehabilitation, such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy.14

Attention is a multidimensional construct,17 encompassing the two dimensions ‘intensity’ and ‘selectivity’, as proposed by van Zomeren and Brouwer.18 Intensity includes alertness (basic readiness to respond to stimuli) and sustained attention (capacity to maintain vigilance over time), while selectivity includes selective attention (ability to filter task-relevant from irrelevant information) and divided attention (ability to manage multiple tasks simultaneously across or within different sensory modalities). Brain injuries can affect all of these components. In a sample of 94 patients affected by a stroke, Barker-Collo et al.19 primarily identified impairments in selective and sustained attention. These findings are corroborated by Hyndman and Ashburn,14 who reported deficits in divided (41%), selective (35%), and sustained (31%) attention. Spaccavento et al.20 confirmed the high incidence of attention deficits in a large sample, with more than 80% of patients impaired in at least one attentional domain, and deficits varying across intensive and selective components. Prevalence and severity were influenced by lesion characteristics, stroke subtype, and time since stroke, highlighting the role of these factors.

Due to the high prevalence of cognitive impairments and their impact on functional recovery, targeted cognitive interventions are essential in neurological rehabilitation.21 Cognitive rehabilitation is a systematic, functionally-oriented set of therapeutic activities based on assessment of cognitive and behavioural deficits following brain injury.22 Its primary aim is to restore impaired functions,13 but also to improve psychosocial well-being, functional independence, and overall quality of life.16,23,24 In addition to traditional paper-and-pencil exercises administered by a therapist, computer-assisted cognitive training (CCT) is increasingly used, offering several advantages such as multisensory stimulus presentation, adaptive difficulty, precise response tracking, and immediate feedback.25 These features are thought to enhance patient engagement, stimulate neural plasticity, and support functional recovery.26 Both conventional and computer-based methods can be integrated within a comprehensive, multidisciplinary rehabilitation framework that includes other cognitive remediation techniques and psychosocial interventions.27 Recent evidence suggests that CCT is particularly effective when targeting higher-order attentional processes, with the strongest effects observed for divided attention.25

Given the growing use of CCT and its potential to enhance patient engagement and neural recovery, further investigations are needed. The present retrospective, observational study therefore examines changes in attentional functioning associated with CCT during subacute neurological rehabilitation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this retrospective, observational study, data from 127 patients undergoing CCT during neurological rehabilitation were analysed. Supplementary information on age, gender, diagnoses, time since onset, treatment duration, and therapy intensity was extracted from the patient records.

Assessment of Attentional Functions

The following subtests of the Test of Attentional Performance (TAP)28 were carried out as part of a standardised examination:

- Alertness: The task is to react as quickly as possible to a visual stimulus without (intrinsic alertness) or with a preceding auditory warning signal (phasic alertness).

- Selective attention (Go/Nogo): The participant is instructed to respond as quickly as possible to a visual target (“x”) while inhibiting responses to a non-target (“+”).

- Divided attention: This subtest includes two conditions: in the visual task, a 4×4 matrix is displayed, and participants have to respond when four crosses form a square. In the auditory task, alternating high and low tones are presented; a response is required when the same tone occurs twice in a row.

Testing took place individually in a quiet room and lasted approximately 1 hour. All assessments were conducted by experienced neuropsychologists who were not blinded to patients’ participation in cognitive training. After a medical history intake (approximately 10 minutes), the TAP subtests were conducted in a fixed sequence. Participants worked independently using written instructions; a practice trial was provided and, if needed, additional verbal explanation to ensure task comprehension.

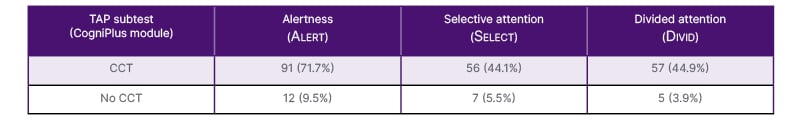

Performance was evaluated based on reaction time metrics (median and SD) and accuracy (errors and omissions) provided by the TAP software. Critical parameters were defined in accordance with the TAP manual and established clinical standards (Table 1). Patients scoring below one SD from normative data (T‑values <40) were classified as impaired and assigned to training in the corresponding attentional domains. To allow comparison across different levels of impairment severity, results are additionally reported using a more conservative threshold (T-values <35, i.e., 1.5 SD below the mean).

After completion of the CCT programme, the TAP assessment was repeated to evaluate training-related changes.

Table 1: Prevalence of attention deficits (T-value <40) and allocation of the corresponding CogniPlus module.

Only patients with T-value <40 are shown. Percentages refer to the total study sample (N=127).

CCT: computer-based cognitive training; CogniPlus: Schuhfried, Mödling, Austria.

After completion of the CCT programme, the TAP assessment was repeated to evaluate training-related changes.

To quantify therapy intensity, the number and duration of therapeutic interventions were retrospectively extracted for each patient, including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, neuropsychological therapy (excluding attention training), and pedagogical therapy. Based on these data, the mean daily number and duration (in minutes) of therapy sessions were calculated for each therapeutic discipline as well as across all disciplines.

Training Programme

Patients exhibiting impairment in at least one TAP subtest were assigned to CCT if they met predefined eligibility criteria, including adequate orientation, the ability to engage for at least 30 minutes, and sufficient capacity to follow written instructions. Training was offered four times per week, with 30-minute sessions conducted in small groups of up to five participants.

The CogniPlus (Schuhfried, Mödling, Austria) programme was implemented, offering adaptive, interactive training modules targeting the following attentional domains:

Alertness (“Alert”): Participants responded to obstacles while riding a motorcycle in a simulated on-screen environment. In condition S1 (phasic alertness), obstacles were announced acoustically and visually, whereas in condition S2 (intrinsic alertness), obstacles appeared unexpectedly within a foggy scene.

Selective attention (“Select”): Participants navigated a mine cart through a tunnel and responded to relevant visual, auditory, or cross-modal stimuli while ignoring distractors.

Divided attention (“Divid”): Participants assumed the role of an airport security officer and were required to simultaneously monitor visual information and auditory announcements, and to respond to predefined target events.

At the end of each training session, participants received individualised feedback on their performance. The total number of training sessions varied depending on individual progress and treatment duration.

Statistical Analysis Statistical analyses were performed using JASP (JASP, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Differences were considered significant at a level of p<0.05. To control for multiple comparisons, p values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction for training-related pre-post changes in TAP outcome measures within each attention domain. Accordingly, four tests were conducted for alertness (αadj=0.0125), three tests for selective attention (αadj=0.0167), and eight tests for divided attention (αadj=0.00625). Other analyses (group comparisons and correlations) were considered exploratory and were not adjusted for multiple testing.

Pre-post changes in continuous outcome measures were analysed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and the magnitude of change was quantified using Cohen’s d. Group differences were examined using the Mann–Whitney U test for comparisons between two groups and the Kruskal–Wallis test for comparisons involving more than two groups. Differences in frequencies or proportions were analysed using the χ² test. Associations between continuous variables were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

For graphical representations, data are presented as mean values with the standard error of the mean.

RESULTS

A total of 127 patients were included in the study (79 men and 48 women). The mean age was 46.58±13.12 years, with a range of 18–73 years. At study inclusion, the mean Barthel Index score was 90±15 points. Regarding aetiology, 37.8% of patients had experienced a stroke (n=48), 23.6% a traumatic brain injury (n=30), 15.0% an intracranial haemorrhage (n=19), and 23.6% another cerebral disease (n=30). Most patients (n=70; 55.1%) completed CCT within the first 90 days after the index event (subacute phase; mean: 43.41±22.67 days; range: 8–89 days). The remaining patients participated in CCT more than 90 days post-event (chronic phase; 90–365 days: n=34; 26.8%; >1 year: n=23; 18.1%).

Training-Related Changes of Attentional Functions

Table 1 summarises the prevalence of attention deficits and the allocation of the corresponding CogniPlus modules. CCT was administered to patients who demonstrated impaired performance (T-value <40) in at least one critical parameter of the respective attention component, as indicated by TAP performance (Table 2).

Approximately half of the patients received training targeting a single attention component (n=67; 52.8%), while the remaining patients underwent multi-component training based on TAP results (n=60; 47.2%).

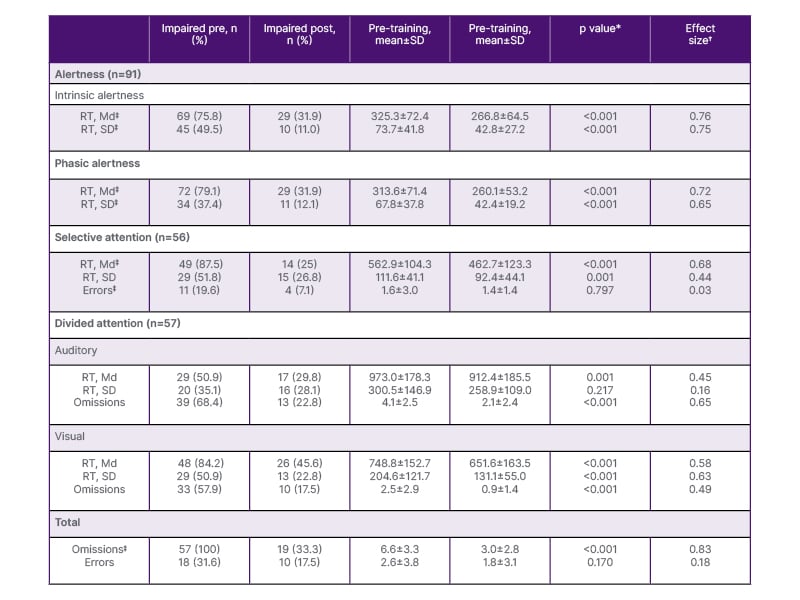

Table 2: Pre-post changes in Test of Attentional Performance outcomes across attention components.

*p values refer to Wilcoxon signed-rank tests; significance was evaluated using Bonferroni-adjusted α-levels within each attention domain.

✝Cohen’s d.

‡Critical parameter.

Md: median; RT: reaction time.

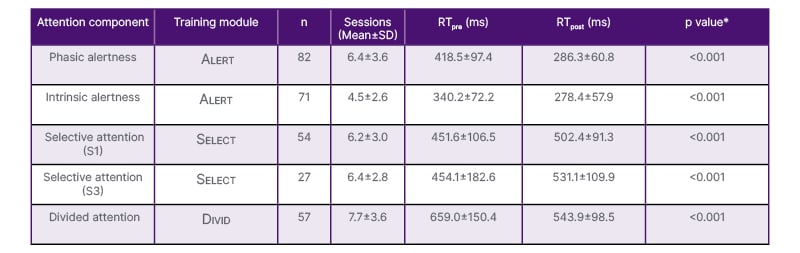

Computer-Based Cognitive Training Results

Training results for the three CogniPlus modules are summarised in Table 3. Reaction times generally decreased across modules, indicating faster responses following cognitive training. An exception was observed in the Select modules, where reaction times increased over the course of training for both the S1 and S3 conditions. This pattern may reflect a speed-accuracy trade-off and increase in task difficulty.

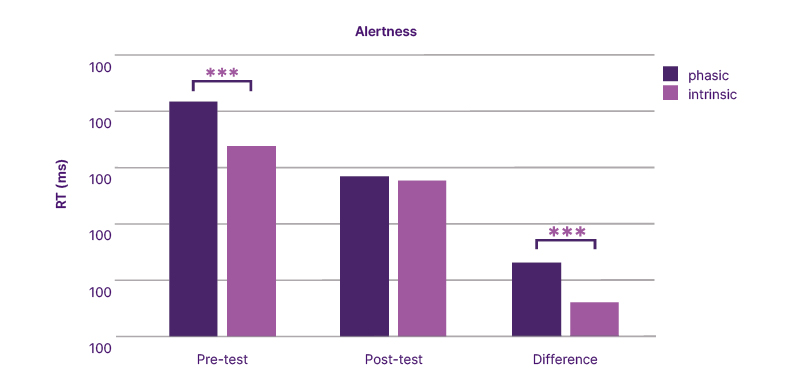

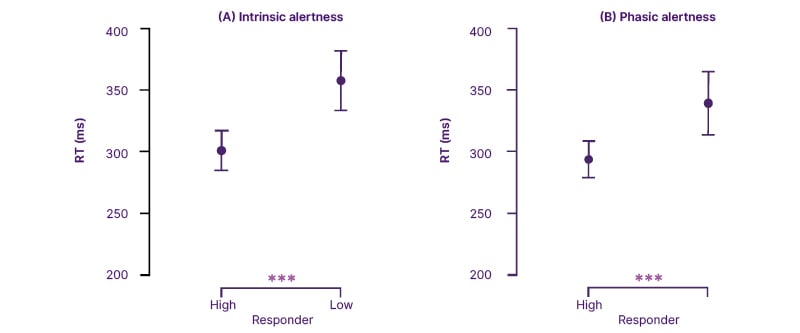

Regarding the Alert modules, reaction times were significantly shorter for intrinsic compared to phasic alertness at baseline (Z=−5.406; p<0.001). After training, this difference was no longer significant (p=0.661), primarily due to a greater improvement in phasic alertness (Z=−5.430; p<0.001), as illustrated in (Figure 1).

Table 3: Pre-post changes in reaction times across attention components.

*p values refer to Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

RT: reaction time.

Figure 1: Changes in median reaction times in intrinsic and phasic alertness before and after attention training.

RT: reaction time.

Test of Attentional Performance Results

Following cognitive training, TAP performance showed improvements across all attention components (Table 2). All reported training-related changes remained significant after Bonferroni correction.

Alertness

Across the entire cohort, the proportion of patients with impaired alertness decreased from 81.1% at baseline to 35.4% at follow-up (χ²=24.205; p<0.001). Training-related changes were observed for reaction time and reaction time variability in both intrinsic and phasic alertness (all p<0.001). Reductions in reaction time were strongly associated with decreases in reaction time variability (intrinsic: r=0.751; phasic: r=0.807; p<0.001). The presence of a warning tone resulted in shorter reaction times both before (Z=−2.737; p=0.006) and after (Z=−2.725; p=0.006) training.

When stratified by baseline severity, patients with more pronounced impairments (T-values <35; n=45) exhibited smaller training-related gains than those with less severe impairments (T-values 35–40; n=46). Group differences were observed for intrinsic reaction time (Z=−3.333; p=0.001), phasic reaction time (Z=−3.980; p<0.001), and reaction time variability in the intrinsic condition (Z=−3.293; p=0.001). Consistent with the severity-based classification, patients in the more severely impaired group already exhibited longer reaction times and greater variability at baseline across both intrinsic and phasic conditions (all p<0.001).

Responder analyses further supported this pattern. Low-responders (n=39) demonstrated greater baseline impairments in both intrinsic (Z=−4.255; p<0.001) and phasic (Z=−3.064; p=0.002) reaction times compared with high-responders (n=52; (Figure 2)).

Figure 2: Comparison of median reaction times in intrinsic and phasic alertness between high and low responder groups.

RT: reaction time.

Selective Attention

The proportion of patients with impaired selective attention decreased from 63 (49.6%) at baseline to 25 (19.7%) following training (χ²=8.674; p=0.003). At baseline, below-average reaction times were more prevalent than elevated error rates (n=49 versus n=11; χ²=33.835; p<0.001). Following Select training, reductions emerged in both reaction time and reaction time variability, whereas error rates remained largely unchanged (Table 2). Improvements in reaction time were associated with greater reductions in reaction time variability (r=0.586; p<0.001).

Severity-based subgroup analyses revealed that patients with more pronounced baseline impairments (T-scores <35; n=26) showed smaller improvements in reaction time than those with milder deficits (T-scores 35–40; n=30; Z=−2.506; p=0.012). In line with this classification, the groups already differed significantly at baseline (Z=−5.933; p<0.001). No significant group differences were observed for error rates, either at baseline or with respect to training-related changes.

Responder analyses showed that low-responders (n=18; 32.1%) tended to achieve smaller improvements in reaction time improvements than high-responders (n=38; 67.9%; Z=−2.281; p=0.023). As expected, high-responders already performed better at baseline (Z=−2.769; p<0.006). No responder-related differences were found for error rates.

Divided Attention

At baseline, 62 patients (48.8%) showed impairments in divided attention, as indicated by the total number of omissions. At follow-up, this proportion decreased to 27 patients (21.3%; χ²=14.641; p<0.001). Training-related improvements were identified in both conditions. In the auditory condition, the number of omissions improved significantly (Z=−4.941; p<0.001), whereas both reaction time measures did not. In the visual condition, all parameters showed significant improvements (all p<0.001). In addition, overall omissions across both tasks, the parameter determining training allocation, decreased significantly (Z=-6.264; p<0.001).

Regarding baseline severity, 43.9% (n=25) and 56.1% (n=32) of patients had T-scores between 35–40 and below 35, respectively. Patients with less severe baseline performance showed greater reductions in omissions during training than those with T-scores below 35 (Z=−3.856; p<0.001). As expected, the groups differed significantly in baseline omissions in both the visual (Z=−3.530; p<0.001) and auditory (Z=−3.400; p<0.001) conditions, while no group differences were observed for baseline reaction time or reaction time improvements.

Among patients receiving divided attention training, 66.7% were classified as high responders and 33.3% as low responders. High responders showed significantly greater training-associated reductions in overall omissions (Z=−3.151; p=0.002) and larger improvements in visual reaction times (Z=−2.742; p=0.006) compared with low responders.

Factors Influencing Training- Associated Outcomes

Subacute versus acute phase: Significant group differences were observed for training-related changes in selective attention. Specifically, the subacute group demonstrated greater improvements in reaction time (Z=−2.490; p=0.013) and reaction time variability (Z=−2.759; p=0.006), than the chronic group. At baseline, no differences were found.

No significant effects of disease duration emerged for any of the remaining parameters.

Indication: No group differences were found for alertness, selective attention, and divided attention across all indications or between individual indications.

Therapy intensity: The mean daily therapy duration was 194.4±38.6 minutes (range: 111–363 minutes). Most patients received therapies from three or four different therapeutic disciplines (89.8%). Physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and pedagogical therapy were the most frequently administered interventions.

Correlational analyses revealed one significant association: longer daily durations of occupational therapy were positively associated with greater improvements in reaction time variability in selective attention (r=0.222; p=0.033). No further significant associations were observed between therapy intensity measures and changes in attentional performance.

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of the present study was to examine training-associated changes of attentional functions following CCT. The study involved a convenience sample of neurological patients enrolled in a specific CCT as part of their ongoing rehabilitation. Accordingly, all participants exhibited some form of attention-related impairment. The findings indicate that participation in CCT was associated with significant pre-post improvements across multiple areas of attention, including alertness, selective attention, and divided attention. Specifically, participants showed improvements in reaction times, reaction time variability, and performance accuracy across the assessed domains, with effect size estimates in the moderate-to-large range. These training-associated changes occurred across different diagnoses and disease durations, suggesting broad applicability of the intervention. However, the presence of a subgroup of low-responders, characterised by more severe baseline impairments, suggests that the degree of initial deficit may modulate the extent of observed training-related improvement.

On the one hand, improvements became directly apparent in the CogniPlus tasks, as reflected by faster reaction times and the successful completion of increasingly complex task levels. However, such gains may in part be attributable to practice-related effects, indicating task-specific learning rather than unequivocal improvement in the underlying attentional processes. To examine whether training-associated changes extended beyond task-specific performance, the TAP was administered before and after the training period. In this independent assessment, participants also showed improvements in parameters relevant to the attentional components targeted during training, suggesting that the observed changes were not restricted to the training tasks themselves. These findings are consistent with results reported by Sturm et al.,29 who applied a CCT intervention in a sample of 33 patients with vascular or traumatic brain injuries and impairments in at least two attentional components. In that study, training participation was associated with improvements in intensity-related aspects of attention and a reduction in omission errors in divided attention.29

Several studies have demonstrated training-associated improvements in attention and other cognitive functions in neurological populations. Among individuals with stroke or traumatic brain injury, CCT participation has been associated with reduced processing time in a simple selective attention task and improvements across all parameters related to memory.30 Gains in working memory were also observed after computerised memory training, with sustained benefits observed at both 4 and 20 weeks post-training.31 In patients affected by stroke, CCT has been further associated with improvements in attention and memory performance, along with changes in frontal and parietal brain wave activity, whereas no comparable changes were observed in control groups receiving standard rehabilitation.32 These findings suggest that CCT may facilitate neural plasticity and enhance cognitive function. In line with these findings, Yoo et al.33 reported better cognitive outcomes in patients with stroke receiving computerised cognitive rehabilitation compared with those undergoing conventional rehabilitation, while no significant differences were observed in activities of daily living. Similarly, another study has shown that combining standard rehabilitation with CCT is associated with greater improvements across a broad range of neuropsychological measures compared with standard rehabilitation alone.34

The findings of the present study, together with the existing literature, suggest that computerised cognitive rehabilitation may represent a useful complement to traditional training approaches. The use of ecologically oriented platforms such as CogniPlus may better simulate real-world cognitive demands than non-adaptive paper-and-pencil exercises, which could contribute to higher patient engagement and motivation. Moreover, computer-based training offers several practical advantages over traditional methods, including the possibility to individualise exercises according to the patient’s specific cognitive impairment profile. Automated programmes supervised by trained professionals allow for systematic adjustments of task difficulty, duration, and presentation speed. These features have been associated with more efficient training outcomes35 and shorter treatment durations.33 However, due to the demanding nature of the training, its applicability may be limited to individuals with relatively preserved cognitive function and sufficient motivation, which is consistent with the present results indicating smaller training-associated improvements in patients with more severe baseline deficits.

The present sample comprised patients with heterogeneous neurological aetiologies and varying time since onset, reflecting routine clinical practice in neurological rehabilitation. While such heterogeneity enhances external validity, it may also obscure differential responsiveness to CCT. To address this issue, additional analyses examined the influence of disease duration and diagnosis on training-related outcomes. These analyses revealed only limited effects of disease duration, which were confined to selective attention. Specifically, greater training-associated reductions in reaction time and reaction time variability were observed in subacute compared with chronic patients. This pattern suggests that the subacute phase may represent a particularly favourable window for CCT. In contrast, no diagnosis-specific differences in training-associated outcomes were identified, supporting the notion that attentional impairments constitute a common consequence of acquired brain injury. Nevertheless, the heterogeneity of the sample and the limited size of diagnostic subgroups may have reduced sensitivity to detect more subtle condition-specific effects. Future studies with larger, diagnosis-specific cohorts and prospective designs are therefore needed to precisely identify moderators of responsiveness to CCT.

Neurological rehabilitation is inherently multimodal, with CCT representing only one component of an individualised therapeutic programme. In addition to attention training, patients received concurrent therapies such as physiotherapy, occupational, neuropsychological, and pedagogical therapy, all of which may have contributed to cognitive and functional improvements. To explore the potential contribution of concomitant therapies, the frequency and duration of additional therapy sessions were retrospectively correlated with changes in attentional performance. Apart from a small exploratory association between occupational therapy duration and improvements in reaction time variability in selective attention, no consistent relationships between therapy intensity and attentional outcomes were identified. However, the use of routine clinical data limited the assessment of therapy intensity, as session frequency and duration do not capture qualitative aspects of therapeutic content or number of repetitions. Previous research suggests that, particularly in physiotherapy, the number of task repetitions rather than session duration is a key determinant of therapeutic effectiveness, with frequency and duration serving as secondary indicators.36 Given the multimodal nature of rehabilitation, attributing improvements in real-world functioning to a single intervention remains challenging. Nevertheless, attentional functions are central to everyday activities, including social participation, independent living, driving, and work,37 underscoring the clinical relevance of addressing attentional deficits within neurorehabilitation.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

A major strength of this study is the large and clinically heterogeneous sample, encompassing a broad range of neurological aetiologies and levels of impairment. In addition, the domain-specific analytical approach allowed a differentiated examination of training-associated changes across distinct attentional components, providing clinically relevant insights into which aspects of attention appear most amenable to training.

Several limitations should nevertheless be considered. Most importantly, the absence of a control group limits causal interpretation of the observed pre-post changes. Although within-subject comparisons offer valuable information on performance changes over time, the lack of a placebo or active control condition precludes ruling out alternative explanations such as practice effects, expectancy effects, regression to the mean, or spontaneous recovery. The inclusion of a control group was not feasible in the present clinical setting, as CCT constitutes part of standard rehabilitation care for patients with attentional deficits and is routinely delivered in group-based formats to optimise clinical resources. Consequently, spontaneous recovery may have contributed to the observed improvements, particularly given that more than half of the sample was assessed during the subacute phase (<90 days post-event). Spontaneous recovery occurs in parallel to therapeutic interventions, particularly during the early post-stroke period.38 Kwakkel et al.39 have demonstrated that 16–42% of the observed improvements during the first weeks to months after stroke onset in body functions and activities can be explained by time alone. To avoid this confounding effect of time, studies evaluating rehabilitation approaches therefore involve patients in the chronic phase, several months after stroke onset.38 This approach was also adopted in the present study, demonstrating that both subacute and chronic patients showed significant pre-post changes in attentional performance, with differences between these disease durations observed in only one attentional parameter. This finding suggests that cognitive training may also be beneficial in the chronic stage, supporting the notion that attentional functions remain amenable to intervention beyond the period of spontaneous recovery. Conversely, in the subacute phase, where spontaneous recovery is highly likely, it remains difficult to attribute observed improvements exclusively to the training intervention, as changes may reflect a combination of intrinsic recovery processes and therapeutic input. Disentangling these effects is particularly challenging in naturalistic rehabilitation settings without a control group.38 Evidence from a single-case report further indicates that, while spontaneous recovery may precede intervention, targeted cognitive training can induce additional, domain-specific improvements beyond time-related change, with effects that remain stable over time.8

Another limitation is that practice effects cannot be entirely excluded. Nevertheless, the observation of performance improvements not only within the training tasks but also on an independent neuropsychological assessment suggests that changes were not restricted to task-specific learning alone. In addition, assessors were not formally blinded to training participation due to the clinical setting, potentially introducing observer-related bias. With regard to outcome classification, high and low responders were defined based on whether post-training performance reached age-adjusted normative cut-offs. However, this categorical approach may underestimate relevant within-subject improvements, particularly in patients with more severe baseline impairments who demonstrated substantial gains without crossing normative thresholds. To address this limitation, effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were reported alongside categorical outcomes. Accordingly, classification as a low responder should not be interpreted as absence of clinical benefit, but rather as persistence of at least one clinically relevant deficit.

Finally, although the present study focused on specific attentional domains, it did not assess transfer effects to everyday functioning or quality of life. As these outcomes are crucial for determining the broader clinical relevance of cognitive training, future prospective studies should incorporate functional and patient-reported outcome measures, ideally using controlled or cross-over designs with appropriate control interventions.

CONCLUSION

This study contributes to the growing body of evidence examining computer-based cognitive rehabilitation in neurological populations. Despite several limitations, participation in CCT was associated with significant improvements in attentional functions, suggesting that such training may represent a useful complement to traditional rehabilitation approaches. However, further research is necessary to clarify the long-term course of training-associated changes and to determine their relevance for functional recovery and everyday life.