OVERVIEW

Innovations in HealthTech are essential for the sustainability of the UK NHS, yet systemic fragmentation, regulatory complexity, and funding hurdles frequently stifle product development and adoption, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises. The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) funded 14 HealthTech Research Centres (HRC) as national centres of excellence to accelerate the development of medical devices, digital technologies, and in vitro diagnostics, and in September 2024, launched the HRC Network using a federated operational model. This article examines how the federated approach functions as an organisational innovation designed to unify distributed expertise without sacrificing the autonomy of individual centres. Unlike centralised hub-and-spoke models, the HRC Network employs shared leadership and cross-cutting functions to coordinate strategy, influence national policy, and streamline the innovation lifecycle. While acknowledging challenges regarding performance measurement and balancing coordination with agility, the article argues that federation offers a viable solution to ecosystem fragmentation. By leveraging collective influence and resources, the HRC Network supports the NHS 10 Year Health Plan’s objectives, shifting towards digital, community-based, and preventive care, while improving navigation for innovators and driving economic growth within the UK Life Sciences Sector.

INTRODUCTION

Innovations in medical devices, digital technology, and in vitro diagnostics, collectively referred to as HealthTech, represent a principal component of the UK Life Sciences Sector. Growth across this sector is vital for the sustainability of the NHS and features prominently in the recent NHS 10 Year Health Plan, driving the three shifts: analogue to digital, hospital to community, and sickness to prevention.1 However, persistent systemic barriers limit the adoption of HealthTech innovations into the NHS.

Several factors contribute to well-established barriers across the innovation lifecycle. The recently published Life Sciences Sector Plan highlights the range of issues that include: a fragmented infrastructure that hampers innovators’ ability to understand complex processes or find appropriate navigation support; insufficient access to funding and growth capital compared to alternative global markets; regulatory approvals that are complex, expensive, and time-intensive, particularly following Brexit and pandemic delays; and a lack of budget transparency and unclear routes to NHS adoption.2

In the UK, small and medium-sized enterprises and entrepreneurs drive the healthcare innovation market, comprising 85% of all medical technology companies.3 Yet, the resource and financial limitations of small businesses mean that they often struggle most to overcome persistent challenges in bringing innovations to market, and many take their products elsewhere,4 or cease development entirely.2

The NIHR drives research and innovation through funded programmes that focus on health and social care research needs, including clinical priorities. Supporting UK Life Sciences and NHS priorities, the NIHR funded 14 HRCs with distinct therapeutic focus, as national centres of excellence that accelerate development of medical devices, digital technologies, and in vitro diagnostics. Hosted by NHS Trusts, they sit at the interface between translational research, commercial product development, and healthcare adoption, working across the NHS, academia, and industry, and with patients at their core. HRCs support the development, evaluation, and validation of new health innovations by providing access to clinical expertise, health economists, statisticians, patient communities, and specialist facilities for clinical evaluations and trials.

In September 2024, the NIHR launched the HRC Network to support these centres using a federated structure. This article examines how this model attempts to address systemic fragmentation, drawing on early evidence and reflecting on what federated approaches might offer the healthcare innovation infrastructure more broadly.

WHAT FEDERATION MEANS

Service delivery frameworks offer distinct operational advantages depending on the sector. The NHS utilises a ‘hub and spoke’ model to centralise high-volume processes (e.g., pathology) while retaining local specialisation. In contrast, research organisations typically favour the ‘Principal Investigator’ model, a decentralised approach where autonomous leaders recruit transient teams for specific projects.

Federation is an alternative model that enables separate organisations to operate independently, retaining their unique specialisms and identity, while also working in unison, following coordinated systems of governance, processes, and standards. Rather than creating a centralised organisation that directs all activity, or leaving centres entirely independent, the federated model distributes governance and, where applicable, funding across participating centres whilst establishing collaboration mechanisms.

Many of the challenges experienced in federated models stem from distinct local procedural and governance structures. While these are fundamental to the effective management of domain-specific nuances (e.g., different clinical pathways or technologies), they can result in operational inconsistencies (e.g., reporting, duplication, or interoperability) between centres. This tension between local autonomy and standardisation requires careful management to maintain local expertise whilst harnessing collective potential.

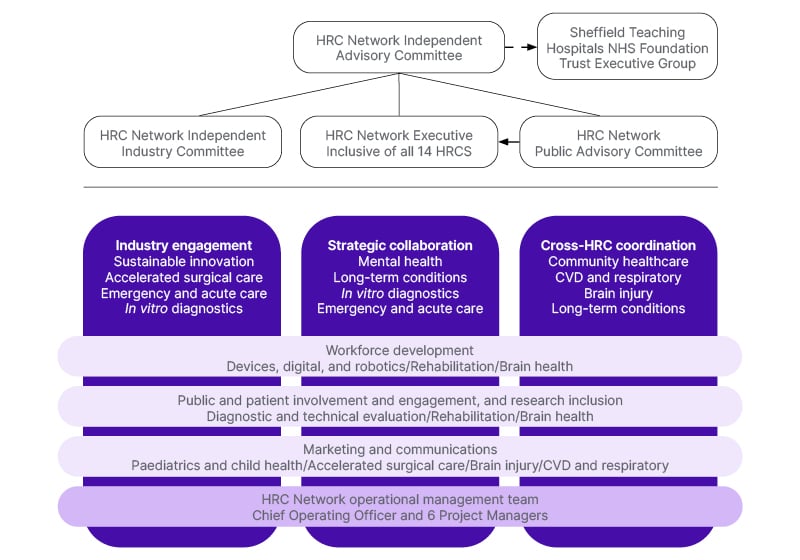

The HRC Network uses a federated model to coordinate strategically through shared leadership and common functions. Operational support is delivered across six cross-cutting functions, each with a dedicated project manager: industry engagement, strategic collaborations, cross-HRC coordination, workforce development, involvement and inclusion, and communications (Figure 1). Each function takes strategic and operational direction from designated HRC leads, distributing stewardship directly to expertise within the HRCs, while being centrally coordinated by the HRC Network. Functions achieve consensus from the HRC Network Executive, the collective governing body that draws on expertise from all 14 centres and the HRC Network.

The federated model differs fundamentally from hub and spoke models with central coordination, or franchise models with standardised processes set centrally. For HRCs, distributed, multi-centre functions operate autonomously while coalescing on agreed governance, strategies, and protocols. This enables quick and agile delivery of work that has been validated at the executive level, enabling collective impact that individual centres could not achieve alone.

Figure 1: Federated governance structure detailing HealthTech Research Centres support and independent governing bodies.

CVD: cardiovascular disease; HRC: HealthTech Research Centres.

THE CHALLENGE OF FRAGMENTATION

The UK HealthTech ecosystem has evolved in a fragmented way that has created deep and persistent challenges for innovators in getting their products into use across healthcare systems.5 Across the full product development lifecycle, there are many critical dependencies between key players that are too undervalued and receive insufficient priority, from patients and the public, to researchers and clinicians. However, data collected from HRC industry partners has confirmed that navigating the ecosystem to find and foster appropriate expertise is very challenging. Connecting the HRCs in a federated way enhances access to academics and healthcare professionals, as well as patients and the public, with dedicated experts leading impactful initiatives. Individually, HRCs successfully foster regional community partnerships, but their national remit requires access to national cohorts of patients, which is best achieved using a federated approach. This is exemplified through the patient involvement function, which aims to connect HRC community groups nationally to enable managed access to lived experience across a range of diverse national cohorts. This co-produced initiative will generate an incredibly valuable resource that would be prohibitively complex for single centres to achieve independently.

The expertise located across the HRCs is well established. Prior to the NIHR commissioning of HRCs and the HRC Network, 11 of these 14 centres operated as MedTech and in vitro diagnostic cooperatives. In fact, many of these centres of excellence have been supporting HealthTech innovation for decades. Historically, they evolved and operated independently, and their expertise was often siloed. These centres, however excellent, lacked connectedness and a unifying voice that could leverage their collective expertise, impact, and influence at national policy or regulatory frameworks, or coordinate responses to government priorities and funding opportunities. Using federation, the HRC Network coordinated a collective HRC response to the NHS 10-year workforce plan, indicating both skills and gaps across the HealthTech landscape, and proposing solutions collectively designed by the federated workforce function experts and validated across the remaining HRCs. This coordinated consultation highlights the value of utilising expertise to steer an important coordinated response, the efficiencies of reduced duplication, and the enhanced impact and influence of one coordinated response.

HOW FEDERATION WORKS IN PRACTICE

The vision of the HRC Network, to unite and harness the expertise from across 14 centres of excellence, means that they can achieve more together than individually. Together, HRCs can identify national and regional priorities and co-produce solutions across multiple domains and with stakeholders throughout the infrastructure. Cross-HRC methodology groups are driving advances from usability testing to AI applications. Integrating and maximising resource effectiveness, such as sharing best practice case studies, supports operational efficiencies like reducing duplication and streamlining processes that translate to productivity gains for HRCs and innovators. Connecting communities of patients, innovators, funders, and supporting organisations nationally enhances individual HRC reach, and raising the profile of each HRC will bolster innovation pipelines and reinforce their standing as a trusted partner for innovators.

The Network operates a Collaboration Challenge Fund supporting cross-HRC research projects that leverage collective expertise rather than single centre capabilities. This creates opportunities for centres with methodological strengths to partner with those having specific clinical capabilities or patient populations. For innovators, increasing their access to the HRC national capacity can accelerate product development and evaluation, and offers greater potential for widespread adoption. All HRCs submitted applications for the initial round of funding. From a total of nine applications, four were awarded with a total value of 155 thousand GBP, which was shared across nine of the 14 HRCs. All applications were required to demonstrate alignment with current NHS priorities and value to health systems or outcomes. Applications were assessed by a panel of experts, including public involvement. Awarded projects included validating an assessment tool in diverse populations; a novel proof-of-concept measurement tool; synthesising social care evidence; and implementing technology to address physical and cognitive frailty. Projects are all currently underway and are due to be completed by September 2026.

STRATEGIC POSITIONING AND SYSTEMIC CHANGE

The HRC Network is uniquely positioned to influence the HealthTech ecosystem through collating and leveraging HRC expertise and impact. A collective, harmonised voice has greater influence to support national challenges and priorities, contribute to consultations, inform policy developments, and guide strategic initiatives. Enabling access to 14 centres of excellence via one coordinating network affords attractive efficiencies to institutions and organisations undertaking significant ecosystem change. As such, ongoing consultations with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) on regulatory framework reform, with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) on value-based procurement processes and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) on initiatives aligned with government health and economic growth priorities, demonstrate real value across the landscape. While these are not formal consultations, they represent the growing influence of the HRCs through the strategic leadership of the federated network, with governing bodies approaching the network to coordinate collective responses.

The model’s approach is valued for its replicability. Following the HRC Network’s establishment, NIHR is launching networks within other infrastructure modelled on this federated structure, suggesting the organisational architecture has merit beyond its initial purpose. This assumed endorsement is based on implementation across other NIHR infrastructure networks, and although the HRC organisational structure is more established, its success, and that of the others over time, could lead to a more formal endorsement across other infrastructure functions.

CHALLENGES

Federation creates its own complexities. Industry partners sometimes seek single-point-of-contact simplicity, which distributed governance cannot fully provide, given the scale and diversity of expertise involved. Balancing central coordination with individual centre autonomy requires considered approaches. Some activities benefit from coordination, others from allowing centres to operate independently based on particular strengths and local relationships. The Network’s workforce strategy employs a coordinated induction process that combines consistency with clinical depth. While every new staff member completes a standardised suite of core modules to ensure operational consistency across all HRCs, individual HRCs preserve their unique clinical identity through delivering bespoke training packages tailored specifically to their specialisms.

Performance measurement presents challenges. Traditional academic metrics like publications and grant income capture some success dimensions but miss others. How should the Network measure its contribution to NHS adoption of innovations, to company growth and sustainability, or to addressing health inequalities through inclusive research design? These questions require ongoing consideration.

The purpose of the Network is to support, unite, and leverage the expertise, impact, and influence of the HRCs, but it is difficult to quantify how much of their individual growth and success can be attributed to the influence of strategic federated leadership. By harnessing the collective influence of the HRCs and fostering strategic collaborations with influential stakeholders in the ecosystem, the Network can advocate for efficiencies in procedures and policy and alleviate barriers to expedite product development and adoption into the NHS. Other enablers of NHS adoption include engaging patients with lived experience to support implementation and deployments, e.g., supporting content for instructions and guidance, and training for NHS staff and patients.

Questions remain about optimal scale and scope. The Network supports connections and facilitates collaborations between clinicians, scientists, engineers, researchers, innovators, and patients with lived experience from NHS Trusts, universities, businesses, and communities, and more broadly to other relevant infrastructure and policymakers. Improving access to expertise embedded throughout the HealthTech landscape should help innovators to progress their products with greater efficiency. Working with HRCs does not guarantee NHS adoption, but the expertise offered positions innovators to be more prepared for procurement. Accessing and utilising the full suite of support available from HRCs can help products move more efficiently from pilot phase to scaled adoption. Coordinating access to HRC and other ecosystem expertise centrally has the potential to create a more equitable process for innovators, and ongoing evaluation of this will be important to validate success.

The Network must strive to maximise efficiencies without becoming another navigational obstacle. An important driver for the Network is to improve how innovators navigate this complex ecosystem. It is necessary to balance identifying and implementing opportunities to simplify the process, whilst maintaining the necessary governance, ethical, and security assurances when dealing with NHS Trusts, patients, and data. Maintaining agility whilst achieving coordination requires careful judgement about which activities genuinely benefit from network-level intervention. For the federation to remain agile, decisions must focus on collectively achievable value that could not be achieved individually.

IMPLICATIONS

The federated approach addresses existing fragmentation by supporting distributed expertise whilst creating coordination mechanisms to unify and leverage expertise and impact. The healthcare system is currently undergoing significant reform, driven by the NHS 10 Year Health Plan emphasising shifts from analogue to digital, hospital to community, and sickness to prevention, all areas where HealthTech innovations contribute substantially. The federated approach enables quicker and more agile service delivery, with HealthTech experts providing strategic and operational direction through these changes.

As with any complex system, proactive risk management is essential to identify, monitor, and mitigate potential challenges. A primary initial focus was ensuring full HRC engagement across the federated model. The federated strategy, which empowers HRCs to lead initiatives aligned with their specific expertise and interests, effectively cultivates higher levels of engagement and ownership.

Furthermore, by design, the federated model embeds systemic resilience. Because functions operate independently, localised challenges do not compromise the integrity of the wider system, which enables implementation of isolated refinements without disrupting overall performance.

Beyond operational risks, the strategic impact on the ecosystem also warrants risk mitigation. The possibility that the federated approach of the Network had a limited or negative impact through excessive administrative burden, increased layers of navigation resulting in product stagnation, was considered and is being monitored. However, evidence generated from a range of stakeholders, including NIHR, innovators, and HRCs, has been overwhelmingly positive, inducing that the federated model has enabled rapid delivery of expert-led initiatives, events, and strategies that catalyse cross-disciplinary knowledge exchange. The HRC Brain Health Innovation event held at the Science Gallery in London, UK, achieved a 100% success rate in improving industry understanding of the HealthTech landscape.

Ultimately, success is broad. For innovators, it means simpler processes, easier navigation, more efficient regulatory systems, and more accessible routes to NHS adoption. For the NHS, it means greater benefit to the healthcare system, to patients receiving treatments, and to the public through prevention. For the government and the UK economy, it means the retention of talented innovators and intellectual property in the UK market, supporting real economic growth.

For the HRCs and Network, success means demonstrating that federated approaches can deliver agile operational and strategic change, enabling and upskilling the workforce whilst mobilising knowledge and expertise from across the 14 centres and their partners, and balancing daily pressures whilst contributing to national growth and transformation.

Whether this model proves to be the right organisational innovation to address healthcare innovation barriers requires sustained evaluation through evidence rather than assumption. It is important to note that the model’s effectiveness remains to be empirically tested and that future evaluation is essential. The model represents a deliberate attempt to address identified systemic problems, grounded in the recognition that fragmentation creates genuine barriers for HealthTech development.

CONCLUSION

Challenges across the HealthTech landscape are well-documented, persistent, and particularly affect small businesses. These include a fragmented infrastructure, complex regulatory pathways, and unclear routes to NHS adoption. The federated approach of the HRC Network attempts to redress these. This structure allows individual HRCs to maintain their clinical autonomy and unique identities while operating under coordinated governance and shared strategic functions. Led by experts within HRCs, strategic and cross-cutting functions aim to unite and leverage the expertise, impact, and influence of 14 HRCs, fostering collaboration, knowledge exchange, and influencing the processes and policies that govern HealthTech development, regulation, and adoption.

Early evidence suggests that this model enables the rapid delivery of important services, strategies, and activities. While challenges remain, such as balancing central coordination with local autonomy and developing new performance metrics, this federated architecture has already been replicated elsewhere in other NIHR infrastructure networks. Monitoring of progress is essential to maintain operational consistency and quality, and the Network recommends publishing full annual reports with delivery against key performance indicators and defined NIHR objectives. It will also be important to conduct a full cost-benefit analysis at the mid- and end-point of the programme to demonstrate the value and impact, and return on investment. The HRC Network welcomes a full independent empirical evaluation of the service and federated approach. It will take some time to realise the full potential of the Network and assess its value and impact. Success will ultimately be measured by whether this model can provide a more equitable, efficient pathway for innovations to move from concept to NHS adoption.