BACKGROUND AND AIMS

Studies have shown that bedside nurses, who are vital members of the healthcare team, are often under-utilised in antimicrobial stewardship (AS) activities.1 Several nursing responsibilities such as taking allergy history and obtaining cultures already overlap with AS activities and they can play a key role in promoting AS in resource-limited settings.2,3 Nursing involvement in AS is required by The Joint Commission.4 The AS team at the authors’ institution (390-bed community hospital) wanted to educate front-line staff nurses regarding AS and incorporate some best practices in daily workflow. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, face-to-face education was not feasible. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the baseline attitudes and beliefs of front-line staff nurses towards AS and see if a virtual education campaign consisting of newsletters and tip sheets would positively impact those beliefs and attitudes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The authors conducted a baseline survey in September 2020. Subsequently, they started distributing monthly newsletters via email. The nurse managers distributed emails and posted content on various AS topics such as obtaining an accurate allergy history, starting antibiotics promptly, using microbiology results to help guide decisions, and stopping therapy in cases of colonisation. A follow-up 6-month survey was conducted in March 2021 to assess the impact of the virtual education. Demographics and survey results were evaluated using X2 and Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate.

RESULTS

A total of 109 nurses responded to the baseline pre-survey in October 2020 compared to 64 nurses in March 2021. The baseline demographics were similar between the pre- and post-survey group in terms of education and primary role as a nurse. All adult specialties were well represented (intensive care units and medical and surgical nurses). Of those who responded in the pre-survey, 98% thought it was very important to obtain cultures accurately and understood the relationship between Clostridium difficile and antibiotics, and 96% of nurses surveyed agreed that nurses should participate in AS activities. The majority of nurses in the baseline survey (93%) believed that emerging resistance is an urgent threat to healthcare. The majority of pre-survey respondents listed knowledge gaps in microbiology (86%), antibiotics (84%), and scope of practice concerns (75%) as barriers to nurse participation.

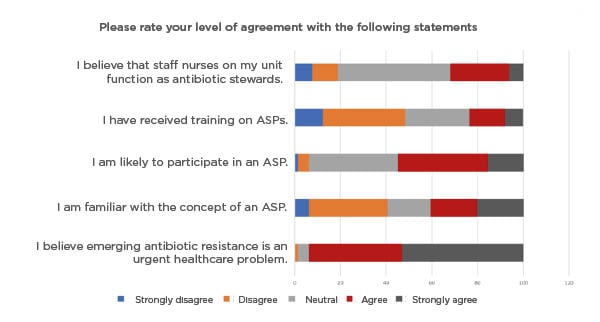

The virtual education raised the familiarity with the AS programme, and more nurses in the follow-up survey said they were familiar with the concept of AS (32% pre- versus 41% post-education; p=0.02) and were likely to participate in AS (52% pre- versus 55% post-education; p=not significant) after the virtual education. Fewer nurses disagreed that staff nurses function as antibiotic stewards (36% pre- versus 19% post-education; p=0.0004) (Figure 1). However, no change was demonstrated in perceived barriers to nurse participation in AS activities despite education and no significant changes were noted in nursing attitudes towards various AS tasks pre- and post-education.

Figure 1: Nursing awareness of antimicrobial stewardship; post-survey percentage of respondants (N=64).

ASP: antibiotic stewardship programme.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that the majority of nurses (>90%) are aware of the threat of antibiotic resistance and want to participate in AS activities. However, barriers to nursing involvement such as lack of knowledge, scope of practice concerns, and time constraints persist. Virtual education may increase nurse awareness of an AS, but needs to be supplemented with formal training and/or face-to-face education. When real-time, face-to-face instruction is not feasible, as in the COVID-19 era, virtual education via email, newsletters, and continuing medical education may supplement traditional methods to improve nursing participation in AS initiatives in an inpatient hospital setting.