Abstract

Background: HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with daily oral emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide has been found to be safe and effective in substantially reducing HIV acquisition in high-risk persons. The US Public Health Service PrEP guideline offers recommendations for the screening and vaccination for hepatitis B virus (HBV) in patients who are prescribed oral PrEP. The goal of this study was to compare guideline adherence to the rate of HBV screening and vaccination.

Methods: This study was a retrospective comparative study evaluating the rate of HBV screening and vaccination in patients ≥18 years old and received a prescription for oral PrEP at the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System (UI Health), Chicago, USA, during two time periods, July 1, 2014–September 30, 2018 (Cohort 1) and October 1, 2018–October 1, 2022 (Cohort 2). Patients currently receiving HBV treatment or with a positive HIV immunoassay blood test at baseline screening were excluded. The primary outcome was comparing appropriate screening and vaccination rates for HBV according to the US Public Health Service PrEP guideline and the CDC, respectively.

Results: A total of 145 patients were included in Cohort 1. The data for these patients were collected through a previous, unpublished study conducted at UI Health and served as historical control data. Of the 230 patients screened for Cohort 2, 145 were included. HBV serology testing prior to PrEP initiation occurred in 78.6% of patients in Cohort 1 compared to 67.6% of patients in Cohort 2, which was statistically significant (p=0.034). HBV vaccine series were initiated by or at first follow-up in 37.9% of patients in Cohort 1 compared to 21.8% of patients in Cohort 2 (p=0.035).

Conclusion: Among patients at UI Health, there was a decrease in HBV screening and vaccination rates in patients within Cohort 2 compared to Cohort 1. There was also a statistically significant difference in human papillomavirus vaccination between both cohorts. Overall, there is an increased need for education among providers prescribing oral PrEP.

Key Points

1. Appropriate screening for hepatitis B virus (HBV) when prescribing oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) remains suboptimal despite oral PrEP receiving approval more than 10 years ago.2. Upon HBV screening, vaccination rates against HBV continue to remain low.

3. All individuals initiating oral PrEP should receive HBV screening prior to initiation, and HBV vaccination should be offered to those without immunity to HBV.

INTRODUCTION

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with oral daily emtricitabine (FTC)/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) or FTC/tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) has been proven to be both safe and effective in reducing HIV acquisition when taken as prescribed.1 Prior to medication management, various strategies have been implemented to assist with the prevention of HIV transmission, including condom distribution, education campaigns, and needle-exchange programs.2-6 Despite these interventions, global HIV transmission continues to occur at alarming rates. FTC/TDF was the first approved HIV prevention option in 2012, used in combination with safe sex practices to reduce HIV-1 transmission. In 2019, another daily oral option for HIV prevention was approved, FTC/TAF, for men and transgender women who are sexually active.

Despite these significant advances in HIV treatment and prevention measures, in 2022, the CDC reported an estimated 31,800 new HIV infections in the United States.7 However, of the 1.2 million people in the United States currently living with HIV, only one in eight people are aware of their HIV status.8 Furthermore, of those with an indication to receive PrEP, only about 36% were prescribed it in 2022.9 This leads to many individuals having the ability to acquire and transmit the virus. In 2021, the US Public Health Service published an update of the PrEP guideline (“Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States: A Clinical Practice Guideline”).1 This guideline offered recommendations for the screening of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in patients prescribed oral PrEP and has been consistent since the guideline was initially published in 2014. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) also recommends vaccination against HBV for all individuals based on its 2022 update.10 The CDC reported approximately 14,000 new HBV diagnoses in 2022.11 There is minimal literature published evaluating guideline adherence to HBV serology testing and documented vaccination adherence in people who are prescribed PrEP. Studies in 2013 and 2017 revealed that prescribers screened for HBV in 61% and 38% of people who were initiated on PrEP, respectively.12,13 Furthermore, in 2015, 4,459 individuals were screened for the iPrEx trial, where only 12% were immune to HBV after vaccination.14

The rationale for providing HBV screening and vaccination recommendations for individuals receiving oral PrEP is twofold.1 The first is to decrease HBV transmission, as risk factors for HBV and HIV transmission remain similar. The second is to ensure proper treatment and monitoring of individuals with HBV infection, given that FTC/TDF and FTC/TAF are approved therapies for HBV, and sudden discontinuation may result in an acute flare of HBV. Furthermore, data highlighting guideline adherence to screening and vaccination of HBV in people prescribed PrEP can serve as guidance to missed opportunities for screening and vaccination administration. This study aimed to assess whether PrEP prescribers at an urban medical center appropriately screened and recommended vaccination administration to people with HBV when initiating oral PrEP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This single-center, retrospective observational study was conducted at the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System (UI Health), a 455-bed tertiary care academic medical center with 26 outpatient clinics located in Chicago, USA. The study received approval from the Office for the Protection of Research Subjects Institutional Review Board, with a waiver of informed consent granted. Adults aged 18 years and older who were prescribed oral PrEP (FTC/TDF or FTC/TAF) at a UI Health outpatient clinic between July 1, 2014–September 30, 2018 (Group 1) and October 1, 2018–October 1, 2022 (Group 2) were considered eligible. People were excluded if they were found to be positive for HIV at baseline screening, receiving treatment for chronic HBV, pregnant, or incarcerated. Missing HBV serologies were assumed to lack the primary objective of interest. Lack of documented serology or vaccination status in the encounter note or laboratory data was coded as no screening or vaccination.

This study evaluated data collected from the two time periods. The period between 2014–2018 served as Group 1, while the period between 2018–2022 served as Group 2. These periods of time were based on when the authors’ institutional protocol on oral PrEP was updated. The major difference in PrEP protocols during the two periods of the study centered around expanded indications for prescribing PrEP, along with institutional education initiatives. Individuals included in this analysis were identified by prescription utilization data.

Data and Outcomes

Data were collected through a retrospective chart review of the electronic medical record (EMR) system at UI Health. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, gender identity, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, weight, height, serum creatinine, and creatinine clearance, were extracted upon initiation of PrEP. Immunization data were obtained from the EMR and Illinois Comprehensive Automated Immunization Registry Exchange (ICARE). For HBV screening and vaccination, the clinic visit date, medication, HIV serology, HBV serology, and documented vaccination history were recorded. To assess adherence to the US Public Health Service guideline and ACIP recommendations published by the CDC, the date that the serologies and documented vaccinations were obtained was recorded.1,10

The primary objective was to determine whether PrEP prescribers at UI Health appropriately screened and recommended vaccination administration for HBV in people initiating PrEP for HIV according to the CDC US Public Health Service guidelines and ACIP recommendations, respectively, since oral PrEP contains agents with activity against HBV. Appropriate screening was defined as HBV serology screening performed at the initial PrEP visit or prior to PrEP initiation. Appropriate vaccination administration was defined as the initiation of the HBV vaccine series by or at the first follow-up visit if HBV serology screening demonstrated a lack of immunity. Secondary outcomes included documentation of immunity to hepatitis A virus (HAV) and HAV vaccination, as well as receipt of human papillomavirus (HPV) and meningococcal vaccinations. These secondary outcomes were included since these infections share common risk factors and transmission routes with HIV.

Statistical Analysis

According to prior data, a 75% incidence of appropriate screening for HBV in Group 1 and a 90% incidence of appropriate screening for HBV in Group 2 were used to establish the effect size. With an α set at 0.05, a sample size of 200 patients was required to achieve 80% statistical power. Data are presented as numbers (percentage) or median [interquartile range], as appropriate. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, depending on suitability. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p-value ≤0.05.

RESULTS

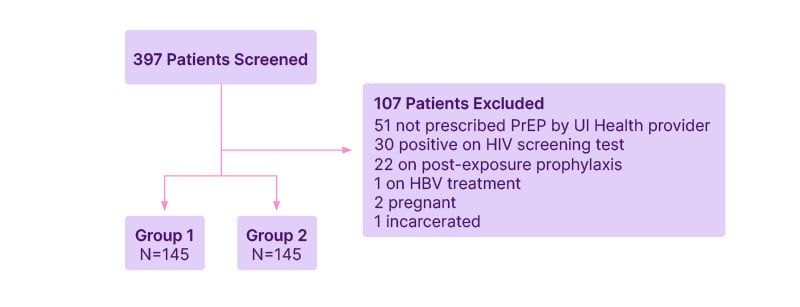

Screening was conducted for 397 individuals, and 290 were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Although people could have met multiple exclusion criteria, the most common reason for exclusion was PrEP not prescribed by a UI Health provider (N=51) and a positive HIV immunoassay at baseline (N=30). Of the 290 people included in the final analysis, 145 were included in Group 1 and 145 were included in Group 2. Demographic information and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1: Diagram for patient inclusion.

HBV: hepatitis B virus; PrEP: pre-exposure prophylaxis; UI Health: University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System.

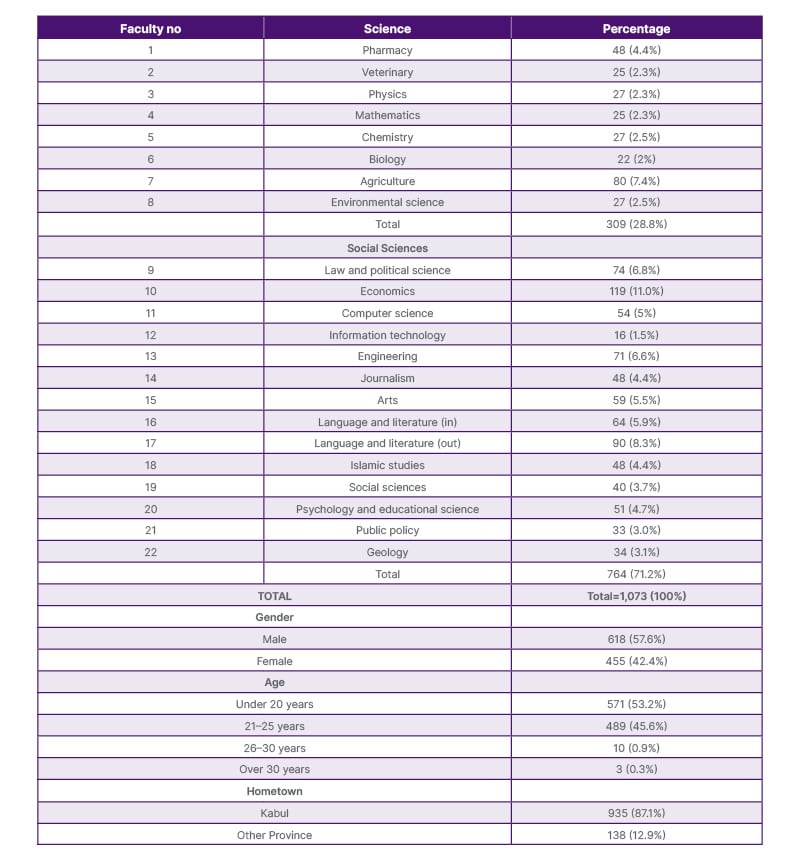

Table 1: Demographics and baseline characteristics.

Data presented as n (%) or median [IQR].

CrCL: creatinine clearance; IQR: interquartile range; UI Health: University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System.

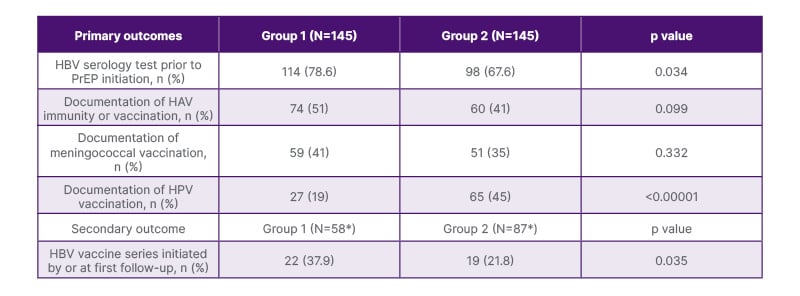

Regarding the primary outcome, prior to PrEP initiation, HBV serology testing was performed in 78.6% of participants in Group 1 versus 67.6% in Group 2 (p=0.034; Table 2). Within the population of screened individuals in Group 1, 40% (58/145) were non-immune to HBV, but only 37.9% (22/58; p=0.035) of these people were initiated on the HBV vaccination series by or at the first follow-up visit. Similarly, within the population of individuals screened in Group 2, 60% (87/145) were found to be non-immune to HBV, but only 21.8% (19/87; p=0.035) of these people started the HBV vaccination series by or at the first follow-up visit. Furthermore, 21.4% (31/145) and 32.4% (47/145) of people were not screened for HBV prior to PrEP initiation at baseline in Groups 1 and 2, respectively (p=0.034). However, 74.2% (23/31) and 61.7% (29/47) of people in Groups 1 and 2, respectively, had no prior HBV immunity or vaccination history documented in the EMR or ICARE (p=0.252). Secondary outcomes included a comparison of vaccination efforts between the groups. No differences existed in the documentation of HAV immunity or vaccination between the groups (p=0.099) or meningococcal vaccination (p=0.332). However, documentation of HPV vaccination was 45% in Group 2 compared with 19% in Group 1 (p<0.00001).

Table 2: Primary and secondary outcomes.

*N represents patients not immune to HBV.

HAV: hepatitis A virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HPV: human papillomavirus; PrEP: pre-exposure prophylaxis.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that prescribers of oral PrEP in outpatient clinics have not increased their efforts to adhere to screening for HBV prior to PrEP initiation over time. Despite the overall decrease, the rate of HBV serology screening at UI Health remains higher than that in the currently available literature (38.3–61.0%).12,13 Of the people who were found to be non-immune to HBV through screening, less than 40% initiated the vaccination series by or at the first follow-up visit. Additionally, more people were screened for HBV and initiated on the vaccination series in Group 1 than in Group 2, demonstrating that prescribers within the family medicine and infectious diseases clinics, as expected, were more aware of guideline recommendations prior to PrEP initiation than providers in other clinical areas, including internal medicine and primary care clinics. This demonstrates a great need for prescribers outside of infectious diseases care to become more familiar with oral PrEP prescribing practices, since these agents are more likely to be covered by prescription insurance. Regardless of the number of individuals screened and vaccinated in both groups, similar to other published studies, there remained a lack of PrEP prescriptions in communities of color, where the incidence of HIV is highest.15 Black and African American individuals represented 40% of estimated HIV infections, yet fewer than 30% received PrEP prescriptions. Similarly, in 2022, only 15% of women eligible for PrEP were prescribed the medication; this is reflected in the study, where most individuals prescribed PrEP were male.16 Overall, PrEP should be offered to everyone regardless of clinical setting, encompassing sexually active individuals who do not disclose behaviors associated with HIV acquisition.1 It is especially important to offer PrEP to men of color, since they carry the highest potential for acquiring HIV based on the reported incidence of HIV. In addition to offering recommendations for the screening and vaccination administration of HBV, the guideline also offers recommendations for HIV screening, renal function tests, and hepatitis C screening for patients initiated on oral PrEP. Unlike oral PrEP options, long-acting cabotegravir and lenacapavir for HIV prevention do not require HBV screening prior to initiation.17-19

In addition to the HBV vaccination administration, it is recommended that people receive HAV, HPV, and meningococcal vaccinations. This study demonstrated that there was no difference in the documentation of HAV immunity or vaccination and meningococcal vaccination. However, the overall percentage of individuals with documented vaccinations in both groups was less than 52%. It is important for people who are on PrEP for HIV prevention to understand the risks of acquiring other infections. Persons with HIV (PWH) are at an increased risk of HAV infection, which can compromise immune defenses.20 HAV viremia tends to be higher with a prolonged duration when PWH are co-infected. The ACIP recommends routine hepatitis A vaccination for all individuals with HIV aged 1 year and older; however, vaccination rates are less than 25%. Similarly, PWH have an 11- to 24-fold increased risk for meningococcal disease due to a low cluster of differentiation (CD)4 count or high viral load.21 A two-dose vaccine series of meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY) for PWH is recommended by ACIP; however, coverage remains as low as 16.3%. The low vaccination administration rates may be due to a lack of recommendations from providers, a fear of adverse effects, and a lack of expected effectiveness. Conversely, documentation of HPV vaccination administration was significantly greater in Group 2 compared to Group 1. It is important to note that guidance on HPV vaccination recommendations changed in June 2019.22 Before June 2019, the ACIP routinely recommended HPV vaccination administration for those aged 11–12 years, with catch-up vaccination advised since 2006 for females up to 26 years old and since 2011 for males up to 21 years old. In June 2019, the ACIP acknowledged that certain individuals aged 27–45 years who were not adequately vaccinated could be at risk for new HPV infections and might benefit from vaccination administration.

The limitations of this study included those inherent to its retrospective, single-center design. Prescriber variability likely impacted the results because Group 1 included only people prescribed PrEP in family medicine or infectious diseases clinics. Prescribers who are less likely to prescribe PrEP because of the patient population they serve, such as those in internal medicine and primary care clinics, may not be aware of the U.S. guidance recommendations prior to prescribing PrEP. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic, a public health emergency, occurred during Group 2. This may have limited access to provider visits, lab draws, and vaccination administration, which is why more prescribers in Group 1 appeared to be adherent to the guidance compared to Group 2. Additionally, because this was a retrospective review, serology or vaccination data were considered incomplete if documentation was missing in the medical record.

The findings of this study underscore the critical importance of adhering to guidelines for HBV screening, as this step is frequently overlooked during the prescription of oral PrEP. Additionally, other options for PrEP may be considered, such as cabotegravir or lenacapavir, as they do not have the same screening requirements for HBV prior to initiation, although screening for HBV is recommended at least once in a person’s lifetime, at minimum. Data derived from this study also guided the need for educational efforts. Areas of future research regarding PrEP care include assessing patient barriers, reviewing vaccination administration refusals and why, as well as evaluating prescriber adherence to the other guideline recommendations for patients starting PrEP, including HIV screening, sexually transmitted infection screening, renal function monitoring, and hepatitis C screening.

CONCLUSION

Despite educational efforts on national and global scales to increase PrEP uptake and prescriber knowledge over time, further efforts are necessary to enhance prescriber adherence to HBV screening and vaccination administration guidelines among patients receiving oral PrEP. A decrease in HBV screening and vaccination administration was observed in Group 2 versus Group 1. The results of this study have the potential to guide other clinics in their efforts to provide optimum PrEP and sexual health care. Interventions that could be implemented to improve appropriate guideline adherence to HBV screening and vaccination administration include the creation of an order, set within the EMR when oral PrEP is ordered, to protocolize PrEP initiation and follow-up; targeted educational initiatives; the creation of pharmacist-led PrEP stewardship programs; or collaborative practice programs involving clinical pharmacists.