INTRODUCTION

The burden of tickborne diseases in the US more than doubled between 2004–2016, with >491,000 cases reported during this period.1 The reasons for the rising incidence of tickborne infections are complex and likely involve a combination of increased recognition and testing by clinicians, improved public health surveillance and reporting, expanding range of ticks due to evolving land use and climate change, and the recognition of new pathogens.2 Early recognition and initiation of directed antimicrobial treatment can be lifesaving.3-5 Thus, it is critical that clinicians working in primary care or urgent care settings consider a diagnosis of tickborne diseases in any patient with possible exposure and a compatible presentation. Knowledge of vector ticks is useful in determining the geographic distribution of diseases (Figure 1) and in considering the possibility of co-infection with a second tickborne agent. This article will focus on important updates in the diagnosis and management of patients in the US with these increasingly common and potentially deadly infections.

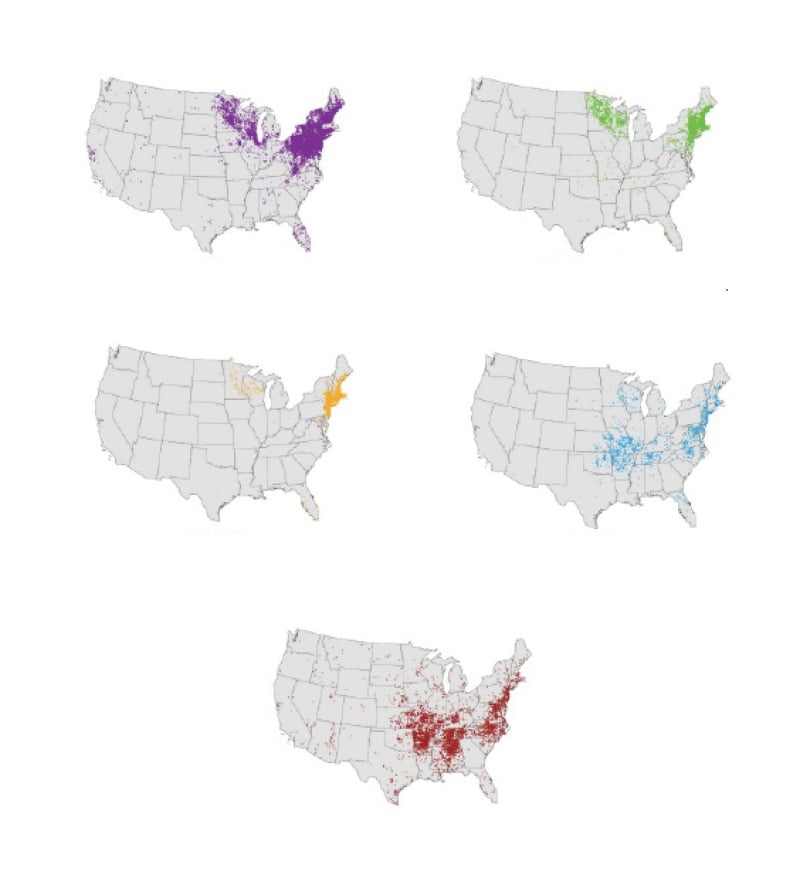

Figure 1: Geographic distribution of selected tickborne diseases reported to the Centers for Disease control and Prevention (CDC), 2018.6

INFECTIONS TRANSMITTED BY BLACKLEGGED TICKS (IXODES SPP)

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease, caused by infection with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, or less commonly, B. mayonii, is the most common tick-borne infection in the US, with almost 90,000 cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2023.7 Passive case reporting grossly underestimates the actual burden of disease. A study using commercial insurance claims estimated that the incidence of Lyme disease is 476,000 cases per year, or more than four-times the number reported to the CDC.8 More than 95% of all cases of Lyme disease occur in the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, and Upper Midwest regions (Figure 1), areas where the blacklegged deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) is most abundant.2 The vector for Lyme disease on the West Coast is Ixodes pacificus or the western blacklegged tick. Notably, the number of counties with a high incidence of Lyme disease has increased by 300% since the 1990s.9

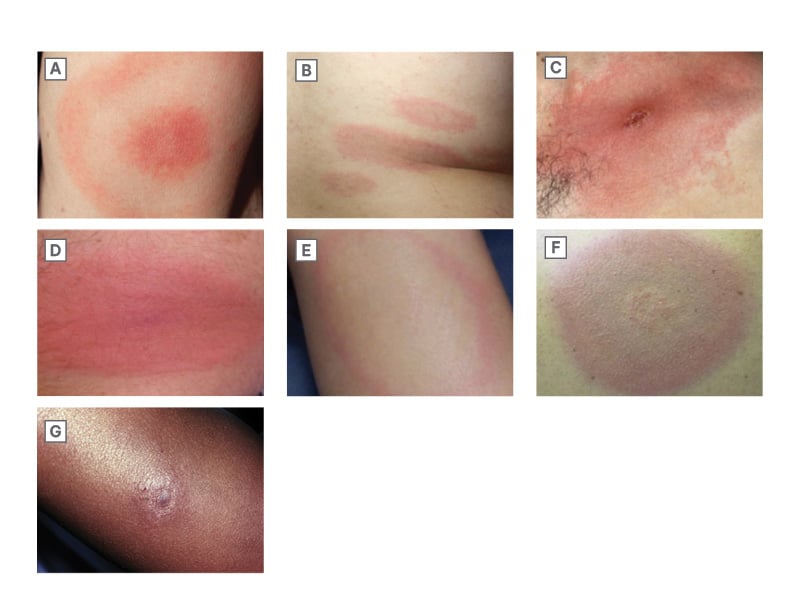

Transmission of B. burgdorferi to human hosts typically requires tick attachment for >24 hours.10 Symptom onset typically occurs 1–2 weeks after infection. Early localized disease manifests as erythema migrans (Figure 2), a target shaped or annular skin eruption at the site of the tick bite that is present in 60–80% of infections. Atypical presentations such as confluent erythema, sometimes with central ulceration, vesicles, or crusting are common,12,13 and a diagnosis of Lyme disease should be considered in any patient with potential exposure to Ixodes ticks presenting with a cutaneous lesion.

Figure 2: Spectrum of erythema migrans skin lesions.11

A) Classic bulls-eye appearance; B) Multiple skin lesions with disseminated infection; C) Confluent erythema with central crusting; D) Erythematous plaque; E) Annular erythema with central clearing; F) Bluish discoloration without central clearing; G) Central nodule in dark skinned patient.

When erythema migrans is not present or not recognized, B. burgdorferi can spread, with disseminated disease occurring 2 weeks–6 months after the initial infection.14 This can present as fevers, multiple erythema migrans lesions at areas distinct from the initial inoculation (Figure 2), carditis (most commonly heart block), or neurologic disease, including cranial neuropathy, polyradiculopathy, or meningoencephalitis.15 Late disseminated disease usually occurs 6 months or later after infection and is characterized by oligoarticular migratory inflammatory arthritis.

The diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease vary based on the stage of infection.15 Early infection may predate the development of antibodies, and therefore, for patients in Lyme endemic areas presenting with erythema migrans, a clinical diagnosis of Lyme disease can be made without laboratory confirmation. Treatment options for patients with erythema migrans and no visceral involvement include oral doxycycline for 10 days, or either amoxicillin or cefuroxime axetil for 14 days.

In the absence of typical erythema migrans, laboratory confirmation is recommended. Clinical Practice Guidelines developed jointly by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommend using a two-tier serologic testing strategy.15 This involves an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) as the first step, and when this is equivocal or positive, a second test is performed for confirmation. With standard two-tier testing, the confirmatory test is a western blot. In 2019, the FDA approved the use of a second sequential EIA, the so-called modified two-tier testing strategy.16 Parenteral treatment with ceftriaxone or penicillin G is recommended for high-grade heart block or parenchymal neurologic disease; cranial neuropathy and meningitis respond to oral doxycycline therapy. Despite appropriate treatment, up to 20% of patients will develop post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome, characterized by fatigue, musculoskeletal pains, disordered sleep, and impaired cognition.17

Anaplasmosis

Anaplasmosis is a bacterial infection caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum that is also transmitted by the Ixodes tick. Coinfection with Lyme disease has been reported in >6% of anaplasmosis cases.18 Reported cases of anaplasmosis in the US have increased >16 fold between 2000–2019.19

Infection may be asymptomatic or associated with nonspecific symptoms such as fever (90%), headache (37%), and myalgias (42%).18 Symptom onset typically occurs between 1–2 weeks following the tick bite. Laboratory abnormalities, including leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver enzymes, support the diagnosis.

Morulae, basophilic inclusion bodies comprised of bacterial clusters, can be identified in the cytoplasm of neutrophils in >20% of cases,20 although the sensitivity of microscopy is highly dependent on the skill and persistence of the microscopist.21 Definitive diagnosis of anaplasmosis is through either whole blood PCR or through serology, with seroconversion or a four-fold rise in titer between acute and convalescent serum diagnostic. Serologic testing is often falsely negative at presentation, as antibodies are only present in a minority of cases early in the course of infection. For this reason, treatment should not be delayed based on a negative acute antibody test.

Doxycycline is first-line therapy for anaplasmosis, with a duration of 10–14 days recommended to treat the possibility of incubating Lyme disease.22 Unlike older tetracyclines, doxycycline is not associated with staining of adult teeth and is indicated for all age groups.23,24 There is limited data to guide therapy for patients who have an absolute contraindication to doxycycline, but case reports have described cure with rifampin.25,26

Babesiosis

Babesiosis is caused by intraerythrocytic protozoan parasites, most commonly Babesia microti, transmitted by the Ixodes tick. Coinfection with both Lyme disease and anaplasmosis has been reported.27 Babesiosis is most prevalent in coastal New England (Figure 1), but can occur throughout the range of the Ixodes tick. Infection can also be transmitted through blood transfusion, solid organ transplantation, or transplacental spread.28 In the former two settings, infection can occur in regions far outside the geographic range of the Ixodes tick.

Approximately 50% of B. microti infections are asymptomatic.29,30 Babesiosis most commonly presents as a nonspecific febrile illness, associated with headache and malaise. Mild hemolysis is the hallmark of infection, and findings of jaundice, scleral icterus, bilirubinuria, or anemia may support the diagnosis. Severe disease is predominantly seen in elderly or immunocompromised patients, including those with asplenia or HIV infection.31 Complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, acute renal failure, congestive heart failure, splenic rupture, and sepsis may occur.28 Laboratory diagnosis of babesiosis is by visualization of intra-erythrocytic parasites on peripheral blood smear or through PCR testing.28 Serologic testing is confounded by the frequency of asymptomatic infection, and seropositivity may therefore simply denote prior infection. The preferred therapy for babesiosis is atovaquone plus azithromycin.32 Ancillary therapy with exchange transfusion is indicated for patients with parasitemia of >10% on blood smear or with severe hemolytic anemia.33

Powassan Virus Infection

Powassan virus is an RNA flavivirus that is also spread by the Ixodes tick. The incidence of Powassan virus in the US is increasing, with most cases reported in the Great Lakes and Northeast regions.34-36 In contrast to Lyme disease, transmission of the Powassan virus can occur in as little as 15 minutes following tick attachment.37 Transmission by blood transfusion has also been reported.38

Symptomatic infection typically occurs within 5 weeks following a tick bite. Most infections present as a nonspecific febrile illness and remain undiagnosed. However, meningoencephalitis occurs in up to a quarter of infections, with a case fatality rate of 10%.39-41 Mortality may be higher in immunosuppressed patients.42,43

Powassan virus infection may be diagnosed serologically or by PCR. Diagnostic tests are not widely available commercially, but may be obtained through consultation with state/territorial health departments when there is a clinical suspicion for infection. There is no effective antiviral therapy, and treatment is supportive care.34

INFECTIONS TRANSMITTED BY THE LONE STAR TICK (AMBLYOMMA AMERICANUM)

Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis refers to human infection caused by Ehrlichia chaffeensis, E. ewingii, or E. muris eauclairensis. E. muris eauclairensis is an uncommon pathogen and, in contrast to the other causes of ehrlichiosis, is spread by the blacklegged deer tick. E. chaffeensis, the most common cause of ehrlichiosis, is widely distributed in the Southeast and along the Eastern seaboard (Figure 1).

E. ewingii, also transmitted by the lone star tick, has a propensity to cause disease in immunocompromised hosts.19,44 The range of the vector tick is expanding, leading to an increased incidence of ehrlichiosis.45 Between 2019–2023, almost half of all cases reported in the US occurred in Arkansas, Missouri, New York, New Jersey, and North Carolina.46

Infection with Ehrlichia spp. commonly causes nonspecific symptoms, including fever, headache, and myalgias.47 A nonspecific macular or maculopapular rash is reported in up to 60% of cases, but primarily occurs in children.48 Laboratory abnormalities are important clues to the diagnosis, with leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver enzymes frequently present. Meningoencephalitis occurs in 5–10% of patients.47,49 Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis may be a life-threatening complication of infection.50

The diagnosis of ehrlichiosis is suggested by visualization of morulae in white blood cell cytoplasm, although microscopy is extremely insensitive.47 The most sensitive diagnostic test for acute infection is whole blood PCR. Serology is useful for retrospective diagnosis when either seroconversion or a four-fold increase in titers is identified. Because only approximately 30% of cases have detectable antibodies at the time of presentation, empiric treatment with doxycycline should not be delayed pending serologic confirmation or stopped based on a negative acute titer. Increased mortality of ehrlichiosis in children45 has been attributed to provider hesitancy to prescribe doxycycline based on prior concerns that tetracyclines cause staining of adult teeth. This has now been disproven,23 and doxycycline is the preferred treatment for all age groups.

Heartland and Bourbon Viruses

Heartland virus (HRTV), which was first identified in northwestern Missouri in 2009,51,52 is endemic to the Midwest and Eastern regions of the US, areas where the lone star tick is prevalent.

Asymptomatic or mild infection is believed to be common.53 Symptoms are identical to those of ehrlichiosis with fever, headache, and myalgias/arthralgias predominating. Similarly, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver enzymes mimic ehrlichiosis. The distinguishing feature is that HRTV infection is not responsive to doxycycline.51 Fatal cases have been reported in immunocompromised patients or those with multiple comorbidities.54-57

Bourbon virus (BRBV) was first identified in an eastern Kansas farmer who died in 2014.58 Human infections with BRBV have been reported in the Midwest, although it is likely widespread throughout regions where the lone star tick is endemic.59-61 Symptoms of BRBV infection are nonspecific, including fever, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and maculopapular rash. Laboratory abnormalities include leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. Although the clinical presentation mimics that of ehrlichiosis, similar to HRTV infection, doxycycline therapy is ineffective, and treatment is supportive care.

Both HRTV and BRBV can be diagnosed through serology or by RT-PCR. Testing can be performed through consultation with state or territorial health departments.

INFECTIONS TRANSMITTED BY DOG TICKS (DERMACENTOR VARIABILIS AND RHIPICEPHALUS SANGUINEUS)

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Other Spotted Fever Rickettsial Diseases

Spotted fever rickettsioses are a group of closely related tick-borne diseases that include Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis, Pacific Coast tick fever, and rickettsialpox. These bacteria cross-react serologically and therefore are not easily differentiated by antibody testing. R. rickettsii, the bacteria causing RMSF, is the most common and virulent of the SFR.62

Historically, the highest incidence of RMSF has been in the Southeast and Southcentral US.63 Since 2003, the incidence of RMSF in the Southwestern US and Northern Mexico has increased significantly, leading to the recognition of the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) as the vector in this region.64 Given the warmer climate in the Southwest, year-round transmission may occur in this region. A history of tick exposure is present in <60% of RMSF cases.65-67

RMSF is characterized by fever, headache, and rash. Early in the course of infection, this triad is present in a minority of cases.68 Specifically, the rash in RMSF, while ultimately present in >80% of patients, appears on average 2–5 days after the onset of fever.65,69 Rash may be absent or unrecognized in elderly or darkly pigmented individuals,70 which may lead to treatment delay and adverse outcome.69

Classically, the rash of RMSF initially presents with macular lesions around the wrists and ankles, followed by the development of diffuse petechiae that spread centrally but spares the face.63,71 Involvement of the palms and soles is noted in 58% of cases.66 Atypical cutaneous findings include pruritus, vesicular lesions, and urticaria.67 Laboratory abnormalities such as thrombocytopenia, elevated hepatic transaminases, and hyponatremia are commonly present.

Neurologic manifestations, including meningoencephalitis, are reported in as many as 40% of cases.62 CSF pleocytosis is often present with a neutrophilic predominance found in one-third of patients.62

Neuroimaging may provide an important clue to the diagnosis. The so-called “starry sky” pattern on MRI, characterized by multifocal diffusion restriction or T2 hyperintense lesions scattered throughout the subcortical and deep white matter, has been reported in both pediatric62,72,73 and adult patients.74

Confirmation of acute RMSF infection is primarily through serologic testing. Interpretation of a single elevated IgG antibody is problematic as this may reflect prior subclinical infection or infection with a cross-reactive pathogen.63,75 IgM antibodies are both insensitive and nonspecific.76 As with other tickborne infections, the initial antibody test is often negative, and therefore, treatment should not be delayed pending serologic confirmation of infection, or stopped based on a negative antibody result. Although not widely available, culture, immunohistochemical staining of skin lesions, or PCR may also be diagnostic.77

Treatment for RMSF in both children and adults is doxycycline given for ≥3 days after defervescence and for a minimum of 5–7 days.63 Longer courses may be indicated for CNS disease. A hallmark of RMSF is that patients typically defervesce within 24–48 hours of starting doxycycline.63,69 Delayed administration of doxycycline is a recognized risk factor for adverse outcomes.4,78,79 There are limited data regarding alternative treatments for patients with severe allergy to tetracyclines, and desensitization should be considered in this setting. Mortality of RMSF in the Southwest is 7–10%,63,69 significantly higher than in other endemic areas.