Interview Summary

The availability of disease-modifying treatments (DMT), including biologic medicines such as monoclonal antibodies, has transformed the treatment field for multiple sclerosis (MS). These high-efficacy therapies can bring substantial benefits to the lives of patients, but their high cost to healthcare systems can limit access. In response, an increasing number of more cost-effective biosimilar medicines have emerged as follow-on medicines after patent expiry of the original biologics. Biosimilar natalizumab (biosim-NTZ; Tyruko®, Sandoz, Basel, Switzerland) is the first biosimilar to be approved by the EMA and US FDA for the treatment of MS. This approval was based upon a comprehensive data package known as the ‘totality of evidence’ (ToE) to confirm biosimilarity to the reference product (ref-NTZ; Tysabri®, Biogen, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). The concept of biosimilars and their impact on the field of MS and neurology as a whole were discussed by neurologists Simon Thebault of McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; and Thomas Berger of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, during interviews conducted by EMJ in June and August 2025. The experts provided insight into the development and approval processes for biosimilar medicines, illustrated by the ToE data package for biosim-NTZ. They also considered

the advantages and challenges that the introduction of biosimilars may bring, and gave their opinions on how the biosimilar paradigm may affect treatment access and the future of patient care in MS.

INTRODUCTION

MS is a chronic, progressive disease that is associated with severe physical and cognitive disability and significant personal, social, and health-economic burden.1,2 The leading financial burden of MS, especially in the early phases of disease, is the cost of treatment and, in particular, the cost of DMTs. DMTs in MS include biologics (e.g., interferons, monoclonal antibodies), alongside chemically synthesised small molecules and non-biologic complex drugs.1 High-efficacy biologic therapies such as monoclonal antibodies can transform the lives of patients by slowing disease progression and reducing the number and severity of relapses.1,3 To date, cost has often been a barrier to widespread patient access,1,2 but patent expiry of many DMTs has opened the way to the development of biosimilars and generic medicines, aiming to deliver the same clinical outcome but at a lower cost.4 Biosim-NTZ has been developed as a biosimilar monoclonal antibody to ref-NTZ for use in treating adults with highly active relapsing-remitting MS.2,5,6 In 2023, it became the first biosimilar in MS to be approved by the FDA and the EMA.2,7,8 Neurologists Thebault and Berger discussed the background, rigorous approval process, and ongoing significance of the biosimilar paradigm.

The experts began by introducing the concept of biological medicines. Thebault explained: “Biologics are complex, high molecular weight proteins that are made in living systems,1 a biological product. Specifically in MS, ‘biologics’ refers to a few different categories of treatments [including] interferons, and monoclonal antibodies like natalizumab, ofatumumab, and alemtuzumab,1 which are widely used. These therapies usually selectively modulate aspects of the immune system and, in the case of natalizumab, block an alpha-4 integrin, preventing immune cell infiltration into the brain.”5,9 Berger continued: “In 1993, the first interferon was approved as not only the first biological treatment in MS, but the first approved MS treatment overall at that time.”10 Thebault said that for neurology, and specifically MS, “it was a completely new era: the biological era.” Over a decade later, the approval of monoclonal antibody treatments in neurology (the first being natalizumab in 2006) was described as revolutionary. “It’s massively changed how effectively we’re able to treat the focal inflammatory injury in the central nervous system, one of the drivers of tissue injury in MS,” said Thebault, “Monoclonal antibodies are the first class of medicines in MS to be considered high efficacy.”

As noted above, the patent expiry of reference branded medications frequently spurs the market entry of generics (for conventional small-molecules), biosimilars (for biologics), and follow-on versions of non-biologic complex drugs.1 Berger observed: “The fate of any treatment is that the patent runs out, leaving the specific drug open to [the development of] either a generic or, in case of biological treatments, a biosimilar.” Referring to the use of the term ‘biosimilar’ in contrast to identical generic copies of synthetic drugs, Berger explained: “There is a microheterogeneity in biological drugs, even in the original drug from batch to batch. This is a matter of nature.” Thebault continued: “Biosimilars are not generics, which I think is an important disambiguation. They are highly similar versions of already approved biologics, which have been established to have no clinically or pharmacodynamically meaningful differences in terms of safety, efficacy, or immunogenicity compared to the reference molecule.”1,11 The EU pioneered the regulation of biosimilars by establishing a framework for their approval, and the first biosimilar was approved by the EMA in 2006.11 Guidelines now exist in both the EU and USA (as well as other regulatory agencies worldwide) to ensure the same standards of pharmaceutical quality, safety, and efficacy apply to all approved biological medicines, whether they are reference biologics or biosimilars.11,12 Reinforcing the importance of this regulation, Thebault commented: “Biosimilarity is a quantifiable concept, and you have to build a structured comparative evidence base. You can’t just claim to be a biosimilar; it’s something you establish after rigorous investigation and product design.”

Both experts articulated that a main benefit of biosimilars lies in the broadening of treatment opportunities, with Berger noting, “it may be a disadvantage for the [original marketing] company, but in terms of the health system, it’s a big advantage: mainly with regard to costs, but also regarding accessibility.” Thebault concurred, adding: “I think it’s a very important concept, but specifically in the context of MS, it allows us to treat more patients earlier, with fewer economic constraints. There is an almost exponential increase in costs incumbent on the healthcare system or insurance provider, based on the advent of biologic therapies, and particularly monoclonal antibodies. Biosimilars are an important way to almost democratise that access. They are also an important part of healthcare sustainability. There used to be an escalation-based treatment paradigm in MS where you started with the cheaper, lower efficacy treatment, and if a patient failed that, you would escalate them; but now we know that is completely inappropriate.” Thebault cited the study by He et al.,13 which showed that the benefits of starting a high-efficacy therapy within 2 years of disease onset could not be regained by a therapy started later in the disease course:13 “So it becomes inexcusable that there’s a barrier to access these high-efficacy treatments, even at the healthcare system level. The cost of some of these monoclonal antibodies is routinely tens of thousands of Canadian dollars a year. That’s obviously not sustainable when you have around 100,000 people in Canada with MS, let alone all the other autoimmune diseases for which these treatments are used. At current rates, the lifetime cost of such treatments is often more than 1 million CAD per patient. The advent of biosimilars [to monoclonal antibodies] offers a route by which we can, in an economically sustainable way, offer these higher efficacy treatments up front.”

Compared to the reference biologics, biosimilars have fewer initial development costs, with less inherent risk in development, which is a key factor in their lower cost to the market. In Europe, strong price negotiations by national health authorities at the point of patent expiry are also critical in lowering costs. However, as Berger explained, problems can arise if drug availability is not negotiated alongside cost: “On the one hand, the originator product is not reimbursed anymore, but if there is a shortfall in the follow-on drug, then suddenly the patient has no drug at all. I think this is something which needs regulatory attention. Drug availability should be secured and assured; otherwise, the merit of the lower costs is [lost].”

DEVELOPMENT AND APPROVAL OF BIOSIMILARS

As already acknowledged, the development of biosimilars differs from that of their reference medicines, but the experts were keen to delineate the equally thorough approval processes required by the authorities.11,12 According to Berger: “There are still a lot of concerns from physicians, and also patients, regarding follow-on products including biosimilars. So I think it’s very important to state that the process of approval for a biosimilar in Europe [by the EMA] is rigorous, with many demands and requests to be fulfilled by the filing company.”11 Thebault observed: “The original medicines [in MS] were based on discoveries, often even serendipitous discoveries, where a molecule that was not initially implicated in MS was found to be efficacious. In the case of biosimilars, there’s no discovery. Instead, we’re trying to match the molecule as closely as we can to the molecule that we know works. In addition, the reference biologic is developed based on a full preclinical workup in mouse models, then Phase I, II, III trials, and Phase IV post-marketing, whereas biosimilars are developed in more of a head-to-head manner, to demonstrate non-inferiority against the reference molecule.” Berger summarised: “The weighting [in development stages] between a reference and a biosimilar drug is different. The biosimilar does not have that major focus on the very early developmental preclinical phase, nor to a lesser extent, in the far-end clinical trial. Rather, the main focus lies in the similarity of biological properties.”1

Totality of Evidence

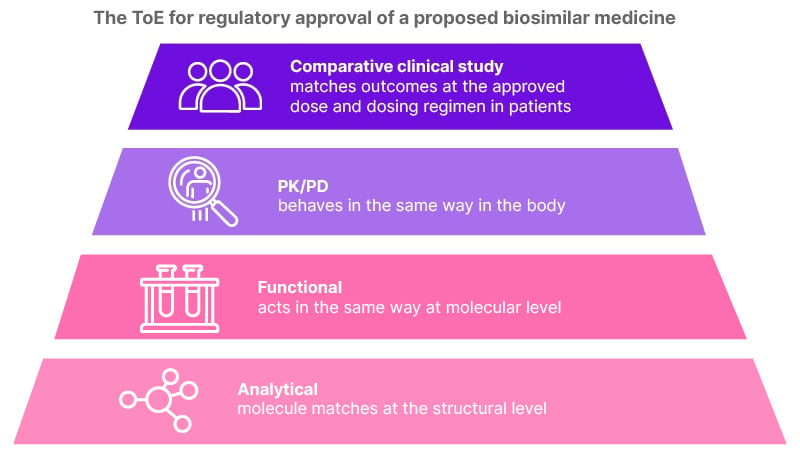

The experts moved on to consider the regulatory framework for approval of biosimilars. “The ToE is a layered regulatory framework that combines analytical, functional, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and clinical data to establish biosimilarity,” said Thebault, who also explained the importance of fully understanding the approval process required by the authorities,11,12 especially in light of the approval of biosim-NTZ. “It’s a new concept for us as neurologists, and I think it’s good to be educated about it because [previous] biosimilars didn’t have to go through this regulatory framework. For example, there is a biosimilar version of rituximab14,15 that is currently used off-label [for MS] in both Europe and North America, and other locations worldwide. Biosim-NTZ is the first European and North American biosimilar approval [in MS].”

The composition of the ToE data package for a biosimilar molecule is illustrated in Figure 1.1,11,12 Beginning with analytical data, the molecule is required to match the reference biologic at the structural level. Berger clarified that the amino acid sequence and the 3D protein structure must be identical, while the post-translational modifications (for example, glycosylation), which show a natural variation in biological molecules, should be within an accepted range of tolerance. In the next stage of evidence, functional equivalence must be proven at the molecular level (involving binding assays and assessment of potency), supplemented by pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data to demonstrate bioequivalence of activity in the body. Finally, there must be clear clinical evidence of similarity in efficacy and safety, and also in immunogenicity, with Berger highlighting that the potential to cause immunological adverse events is a major element of assessment for any biological drug. Likewise, pharmacovigilance is required for all medicines post-approval, and the filing company has to provide a risk-management plan to monitor side effects, with Berger noting the “natural modulation in characteristics of a biological treatment over time.”

Figure 1: Composition of ‘totality of evidence’.

PD: pharmacodynamics; PK: pharmacokinetics; ToE: totality of evidence.

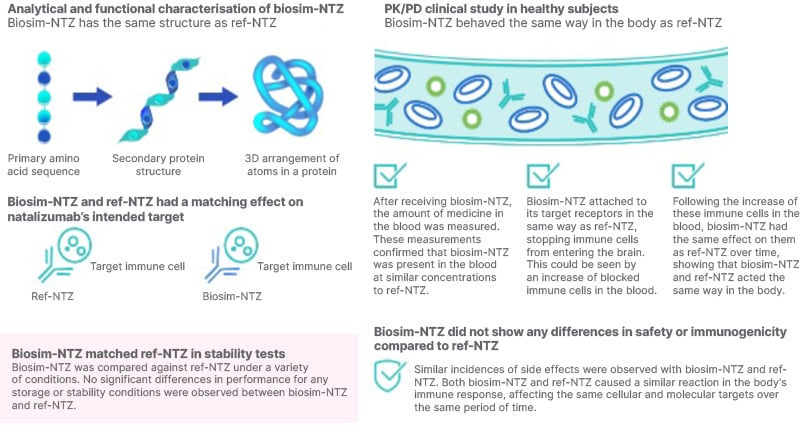

Using biosim-NTZ as an illustration of the ToE package (Figure 2), Thebault said: “Biosim-NTZ has been confirmed to show extensive structural similarity [to ref-NTZ] on the basis of multiple assays.2,5,6 Functionally, it binds the same α4 integrin with a similar affinity, and pharmacokinetically and pharmacodynamically, it’s been demonstrated to be bioequivalent.”2,5,6,9 Berger concurred, commenting that, “the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics are more or less identical, even though the range of tolerance given by the EMA would allow a certain variation. This means the quality is very high and follows the request for similarity quite extensively.” The clinical evidence of biosimilarity was derived from the Phase III Antelope study (NCT04115488),16 a multicentre, randomised, parallel-group, double-blind study over 48 weeks, which compared biosim-NTZ and ref-NTZ in the treatment of 264 patients with relapsing-remitting MS.17 No significant differences between treatment groups were observed in efficacy, safety, or immunogenicity, including the primary endpoint of the cumulative number of new active lesions on MRI over 24 weeks.17 Considering the full ToE package, Thebault concluded that biosim-NTZ “ticks all the boxes for being a true biosimilar that stood up against the framework that the regulatory agencies put in front of us.”

Figure 2: Summary of totality of evidence for biosimilar natalizumab.

biosim-NTZ: biosimilar natalizumab; PD: pharmacodynamics; PK: pharmacokinetics; ref-NTZ: reference natalizumab; ToE: totality of evidence.

IMPACT ON CLINICAL PRACTICE FOR MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

Beyond the regulatory processes, Thebault and Berger moved on to consider the practical impact of the approval of biosim-NTZ in the field of MS, for patients, physicians, and healthcare systems. “For patients, natalizumab is a highly efficacious therapy in the top tier of treatment, and access to this biosimilar will help us broaden and speed access to this treatment,” said Thebault. Berger added: “Even in a consortium like the European community, not every patient has the same access to the same drug. Health-related issues are still a matter of national health politics, so even if the EMA approves a medication for a certain indication, it might be adjusted to national interests with different restrictions and limitations, driven mainly by costs. The idea of a biosimilar is to provide a follow-on drug at a lower cost, so it will constitute a benefit to patients because it’s more likely that the drug will be accessible in settings where previously there were restrictions.”

Regarding the impact of biosim-NTZ on healthcare professionals (HCP), Thebault commented: “It is generally a very good thing in terms of treatment flexibility, cost-effectiveness, and access to a drug that we know works well.” According to Berger, the keyword used by the authorities is ‘interchangeability’, so the substitution of a reference medicine with a biosimilar should have little impact for HCPs and deliver the same clinical outcome. However, Berger cautioned that in practice, “not everyone believes this narrative,” and that there may be a need for more intense patient discussions and counselling during HCP consultations when a biosimilar medicine is introduced.

Berger explained that, for healthcare systems, the greatest impact will come from lower costs (so greater cost-effectiveness) and improved patient access. Thebault added: “As I alluded to before, biosimilars are changing the MS treatment paradigm from escalation to high efficacy upfront. In our field, we call that ‘flipping the pyramid’, and that has an important clinical impact, especially in public healthcare systems, supporting the idea of earlier initiation of high-efficacy treatments and sustained use. The other clinical impact for the health system is that there’s a huge potential for savings, which may just be recouped into an already heavily indebted system, but, in an ideal world, could be reinvested into other MS-related care initiatives, like on-treatment monitoring.”

In contrast, the nocebo effect is one of several challenges and misconceptions that may be encountered with biosimilars in clinical practice, as Thebault explained: “I think another clinical impact for patients is based on what we’ve already seen with generics in MS. That is, the risk of perceived inferiority, which is usually increased [reporting of] non-specific side effects that, unfortunately, results in patients wanting to discontinue or swap their therapy. They have an expectation that the drug is somehow not as good, and that their MS is not being as well managed. It’s not driven by biology; it’s an expectation-based problem, but it has real outcomes. Dealing with this nocebo effect will mean more conversations in clinic discussing these perceived treatment differences; differences that I’ve never yet been able to back up with [evidence from] an MRI scan or clinical exam.”

Another challenge, compounding the nocebo effect, is that the original biologics often come with drug-company funding for a clinical nurse manager to oversee patient care. Thebault noted that the loss of this extra level of support may affect the patient’s experience of biosimilar treatment, including their compliance. Added to this, Berger noted that concerns were sometimes expressed over potential side effects from non-active components of the biosimilar (which are not required to be identical to the reference product). The situation may also be compounded by physicians unfamiliar with the biosimilar concept who share their concerns with the patient. MS most commonly affects individuals aged between 20–40 years old,18 and in Berger’s experience, this young adult population tends to be well informed, but also sceptical about treatment alteration. Berger felt this could be overcome through better education and dissemination of information to patients and physicians, and observed: “I think biosim-NTZ will have an opportunity to foster better understanding among the neurology community and reassure patients. As long as there are still concerns among the medical community, the lower the patient acceptance will be. The EMA approval procedure is tough and rigorous, and if someone understands this, then they will likely accept that the end product is similar to the original.” Thebault concluded: “Initially, I think it’s incumbent on us as clinicians to monitor those who start on this drug very closely. Post-marketing surveillance and registries are going to be essential to help us build confidence among clinicians and patients over time that [in routine clinical practice] the molecules truly are equivalent. Our job here is to build confidence and not undermine trust.”

A FUTURE WITH BIOSIMILARS

Considering the wider context of what the EU/USA approval of biosim-NTZ will mean for MS and for neurology, Thebault described a ‘new phase’ of sustainable, high efficacy treatment in MS. However, he also offered a caution for the future of drug development. “Over the last 20 years, MS has led the field of neurology as the disease paradigm that has rapidly advancing new treatments. That has revolutionised the kind of conversation I can have with patients when they are first diagnosed. I can actually tell them, ‘I can make your life pretty normal. You’re going to do the job, you’re going to have the kids, and it’s probably going to be okay as long as you keep taking this medicine’. So we’ve had that era of rapid innovation, and we’re moving to what could be seen as more value-based neurology: recognising we’re crippling our health systems, and shifting to the idea of sustainability alongside innovation. However, there’s concern that widespread adoption of biosimilars will reduce investment for the discovery side of innovation for new biologics, especially in complex diseases like MS. So, this [adoption] has to be anchored in rigorous science and patient trust, and without completely undermining the next generation of treatments, which would ultimately hurt patients with MS. That said, experience from other therapeutic areas such as oncology and immunology has shown that biosimilars can coexist with (and even support) innovation, by expanding early access to biologics while novel therapeutic classes continue to emerge.19 Ultimately, I think the idea of a value-based model of care can coexist with the discovery- and innovation-based model of care that we’ve had in MS for the last 20 years.”

CONCLUSION

Summarising, Berger stated: “I think the more patients who have appropriate access to an appropriate drug at the appropriate time point, the better the outcome. Therefore, I think that biosim-NTZ is a pacemaker in this way. In some areas of the world, we have a lot of non-comparable, low-quality biosimilars and generics that are detrimental to patients in terms of having lesser efficacy and higher side effects. Biosim-NTZ is a kind of role model, especially in terms of the approval process, because it clearly defines the benchmark for quality assurance in Europe, and probably also for the rest of the world.” Thebault concurred, adding: “I think this is a real test case that will be studied closely beyond our specific narrow field and focus. For example, there are monoclonal antibodies and biologic therapies being deployed for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. It’s important to note that biosimilars like biosim-NTZ arrive on the market with more evidence about what the molecule is and what it does than the original molecule did. It’s also important to highlight that these are not second-best options. They’re scientifically validated, tightly regulated, and have the potential to democratise therapy in MS. As clinicians, it’s incumbent on us to translate that confidence in the product to our patients.”

Biographies

Simon Thebault

Simon Thebault is a neurologist specialising in MS and neuroimmunology at the Montreal Neurological Institute and McGill University Health Centre, Quebec, Canada. His research focuses on developing and translating actionable soluble and immune cell biomarkers to improve patient outcomes. Bridging the gap between laboratory innovation and clinical care, his lab employs advanced detection technologies and multiomic approaches to analyse biospecimens from well-characterised clinical cohorts.

Key research areas include validating the clinical utility of emerging serum biomarkers such as neurofilament light chain and glial fibrillary acidic protein, characterising cerebrospinal fluid protein and immune cell profiles as indicators of CNS-compartmentalised inflammation, and investigating the role of Epstein–Barr virus in priming disease activity in MS, both as a potential biomarker and a therapeutic target.

Thomas Berger

Thomas Berger is Professor of Neurology and Chair of the Department of Neurology at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria. Scientific interests centre on neuroimmunology, with specific focus on inflammatory demyelinating CNS disorders. Berger has published about 500 peer-reviewed journal publications and several books/book chapters, and has been principal investigator in more than 70 clinical treatment trials.

Berger is past-president of the Austrian Society of Neurology, serves as National Multiple Sclerosis Coordinator of the Austrian Society of Neurology, is president of the Multiple Sclerosis Research Foundation in Austria, is a member of various international and national advisory and review boards, and is also actively engaged in the European Academy of Neurology as former Board Member and past-Chair of the Scientific Committee.

| Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information for the United Kingdom can be found at https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/ or search for MHRA Yellow Card in the Google Play or Apple App Store. Adverse events should also be reported to Sandoz Group AG via the online reporting system at https://www.sandoz.uk.com/about-us/contact-us/adverse-event-reporting/ or at [email protected]. |