Meeting Summary

The therapeutic landscape in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is advancing with the investigation of new treatment approaches, used alongside standard-of-care Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) induction and maintenance, that aim to improve long-term outcomes in high-risk patients. This article captures recent advancements and new clinical data in the management of high-risk NMIBC presented at the 2025 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Annual Congress, including key learnings and implications for clinical practice.

The combination of the gold-standard NMIBC treatment, BCG, with immunotherapy is a strategy generating particular scientific interest in high-risk NMIBC based on evidence that increased programmed death-ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression and alterations in immune infiltration are associated with BCG failure. Final results of the POTOMAC study, disclosed at ESMO 2025, showed that adding 1 year of the anti-PD-L1 antibody durvalumab to BCG induction and maintenance reduced the risk of disease recurrence by 32%, highlighting it as a potential new treatment for patients with BCG-naïve, high-risk NMIBC. In contrast, the ALBAN study of another anti-PD-L1 antibody, atezolizumab, also presented at ESMO 2025, failed to show a significant improvement in event-free survival (EFS) versus BCG alone in a similar high-risk NMIBC patient population.

Exploring new and contemporary treatment approaches in high-risk NMIBC offers the opportunity to address existing unmet needs and reduce the risk of disease progression and recurrence. Moving forward, an increased focus on biomarker-driven patient selection and treatment optimization will be important to maximize clinical benefit from systemic immunotherapy used in combination with BCG.

Clinical Context: Unmet Needs in High-Risk Non-muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer

More than 70% of patients with bladder cancer are diagnosed with the non-muscle-invasive subtype, and around 50% of these patients will be classified as high-risk, meaning they have an increased likelihood of disease progression or recurrence due to specific tumor characteristics.1-3

BCG induction and maintenance is the backbone of current treatment for patients with high-risk NMIBC.4,5 Patients typically undergo complete transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT), followed by intravesical instillations of BCG directly into the bladder.4,5 According to the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines on NMIBC, BCG maintenance therapy should be given for a duration of 1–3 years.4

Although patients in the early stages of bladder cancer are treated with the target of cure, early recurrence is common among those with high-risk NMIBC. Patients who experience this early recurrence of high-risk disease or who develop BCG-unresponsive disease have an increased risk of progression to muscle-invasive bladder cancer or metastatic disease.4,5

The current clinical reality is that, despite initial high response rates to BCG therapy, around 40% of patients with high-risk NMIBC experience early recurrence or progression within 2 years.6,7 Estimates suggest that up to 80% of patients will go on to have disease recurrence within 5 years.3,8 This leads to the need for repeated intervention, with more intensive and invasive treatments and procedures, often culminating in complete surgical removal of the bladder via radical cystectomy.4,5

Radical cystectomy itself is an unpopular procedure among patients, and can be associated with significant post-surgical complications, including urinary problems and sexual dysfunction, which negatively impact on patient quality of life (QoL).9 The ongoing global BCG shortage also presents clinical challenges that can adversely affect patient care.10 Several studies have shown higher recurrence rates of NMIBC during times of BCG shortage, which is drivenby both increased demand and supply chain problems.10

Collectively, these unmet needs underscore the need for new strategies in the treatment of high-risk NMIBC that are able to effectively reduce the risk of recurrence or progression in the early stages of disease, and which may ultimately enable a move away from complete reliance on BCG.4,10

Systemic Immunotherapy Plus Bacillus Calmette-Guérin inHigh-Risk Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer

The POTOMAC Trial of Durvalumab

Final results from over 5 years’ follow-up of the Phase III POTOMAC trial of durvalumab in combination with BCG induction and maintenance therapy were presented by Maria De Santis, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany; and Medical University of Vienna, Austria, in a late-breaking proffered paper session at ESMO 2025 that was published simultaneously.11,12

POTOMAC asked the question of whether adding 1 year of systemic immunotherapy with durvalumab to intravesical BCG induction and maintenance could improve outcomes in patients with BCG-naïve, high-risk NMIBC compared with BCG induction and maintenance alone.11,12 Durvalumab is an anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody that blocks the interaction between PD-L1 on tumor cells and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and cluster of differentiation (CD)80 receptors on T cells, thereby enhancing the body’s antitumor immune response.13,14 The mechanistic rationale for combining durvalumab immunotherapy with BCG is that BCG stimulates antitumor T cells, while durvalumab extends the activity of cytotoxic T cells for a more durable response.15,16 Durvalumab is already approved across a range of different cancer types and is indicated in the bladder cancer setting for the treatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer based on results from the Phase III NIAGARA trial.13,17

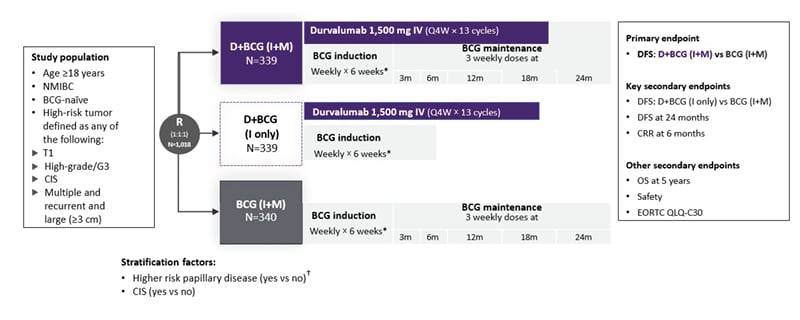

POTOMAC was a randomized, open-label, multicenter, global Phase III trial that evaluated durvalumab plus BCG in 1,018 patients with BCG-naïve, high-risk NMIBC (Figure 1).11,12

Figure 1: POTOMAC: a global, randomized, open-label, Phase III trial.11,18

*For patients with persistent CIS disease at 3 months, a single BCG re-induction was administered weekly for 6 weeks according to local standard practice.

†Defined as T1G3/T1 high-grade or multiple and recurrent and large tumors (those with a diameter of ≥3 cm).

All disease assessments were performed by the investigator.

BCG: Bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CIS: carcinoma in situ; CRR: complete response rate; D: durvalumab; DFS: disease-free survival; EORTC QLQ-C30: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer 30-item Core Quality of Life Questionnaire; G: grade; I: induction; IV: intravenous; m: month; M: maintenance; NMIBC: non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; OS: overall survival; Q4W: every 4 weeks; R: randomization; vs: versus.

This study was conducted in more than 120 centers across 12 countries, including in Europe, Asia, and Canada. The primary endpoint was disease-free survival (DFS), defined as time from randomization to date of first recurrence of high-risk disease or death from any cause, for durvalumab plus BCG induction and maintenance therapy compared to BCG induction and maintenance therapy alone. Key secondary endpoints were DFS for durvalumab plus BCG induction only versus the comparator arm, DFS at 24 months, and complete response (CR) rate at 6 months. Other secondary endpoints included overall survival (OS), safety, and patient QoL, assessed using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer 30-item Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30).11,12

Patients in POTOMAC had undergone TURBT prior to randomization and had high-risk disease defined as any of the following: T1; high-grade/Grade 3; carcinoma in situ (CIS); or multiple and recurrent and large (≥3 cm). Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive durvalumab plus BCG induction and maintenance therapy (D+BCG [I+M]), durvalumab plus BCG induction-only therapy (D+BCG [I only]), or BCG induction and maintenance therapy (BCG [I+M]). Equal numbers of patients (approximately 400) were included in each study arm. The duration of BCG induction and maintenance therapy was 6 weeks and 2 years, respectively.11,12

In general, patient demographic and disease characteristics were well-balanced across the POTOMAC study groups and BCG treatment exposure was similar between the D+BCG (I+M) and BCG (I+M) arms. Patients demonstrated high compliance to BCG treatment, and the median number of maintenance instillations was 14.0 in both the D+BCG (I+M) and BCG (I+M) arms.11,12

POTOMAC met its primary endpoint, showing an early and sustained DFS benefit for D+BCG (I+M) versus BCG (I+M). After a median follow-up of 60.7 months, the durvalumab regimen showed a 32% reduction in the risk of recurrence of high-risk disease or death versus the comparator arm (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.50–0.93; p=0.0154). Estimated median DFS was not yet reached for either arm. The DFS benefit of D+BCG (I+M) versus BCG (I+M) proved generally consistent across patient subgroups.11,12

Although POTOMAC was not statistically powered to test OS, descriptive analysis showed an OS HR of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.53–1.20) over 5 years of follow-up (14% maturity), demonstrating no detriment to OS with the addition of immunotherapy. Adding durvalumab to BCG (I+M) also had no major impact on patient-reported QoL, as evidenced by consistent EORTC QLQ-C30 scores across the POTOMAC study period. For the key secondary endpoint of DFS for D+BCG (I only) versus BCG (I+M), there was no statistically significant difference between study arms (HR: 1.14; 95% CI: 0.86–1.50; p=0.3530).11,12

The safety and tolerability of durvalumab plus BCG induction and maintenance in the POTOMAC trial was consistent with the known safety profiles of the individual therapies, and no unexpected toxicities were identified. Maximum Grade 3 or 4 adverse events (AE) were reported in 34%, 27%, and 17% of the D+BCG (I+M), D+BCG (I only), and BCG (I+M) arms, respectively, while immune-related AEs (irAE) occurred in 27%, 34%, and 1% of the study treatment groups, respectively. Overall, 31% of patients experienced AEs leading to treatment discontinuation in the D+BCG (I+M) arm, compared to 19% on D+BCG (I only) and 20% on BCG (I+M).11,12

Overall, the POTOMAC trial showed that durvalumab in combination with BCG (I+M) resulted in a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in DFS compared to BCG (I+M) alone in patients with BCG-naïve, high-risk NMIBC. At a median follow-up of >5 years, durvalumab achieved a 32% reduction in the risk of a DFS event, and produced an early and sustained DFS benefit starting at less than 4 months. Durvalumab plus BCG (I+M) also showed a tolerable and manageable safety profile, with no reported deaths due to treatment-related AEs.11,12

The ALBAN Trial of Atezolizumab

In direct contrast to POTOMAC, the ALBAN trial, another international, randomized, open-label, Phase III study evaluating immunotherapy in combination with BCG in high-risk NMIBC, failed to show a significant improvement in EFS compared to BCG.19,20

The ALBAN trial was presented at ESMO 2025 by Morgan Rouprêt from Sorbonne University in Paris, France.19 It compared the anti-PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab plus BCG to BCG alone in BCG-naïve patients with high-risk NMIBC. The primary endpoint was investigator-assessed EFS, defined as high- or low-grade NMIBC relapse, persistence of CIS after 6 months, progression of disease, appearance of upper tract urothelial carcinoma, or death. As Rouprêt explained, ALBAN used this deliberately pragmatic definition of EFS, counting any intravesical recurrence (low- or high-grade) as an event because this is an important endpoint for patients, given that any recurrence translates into a TURBT, with associated morbidity, costs, and anxiety. Key secondary endpoints included high-grade recurrence-free survival, CR rate, duration of response in patients with CIS disease, and OS. In total, 517 patients were randomized in the ALBAN trial, 262 in the atezolizumab plus BCG arm and 255 in the BCG only arm, and 97.7% received at least one dose of trial treatment.19,20

Unlike POTOMAC, the ALBAN trial did not meet its primary endpoint. There was no significant difference in EFS with the addition of atezolizumab to BCG versus BCG alone, with an HR of 0.98 (95% CI: 0.71–1.36; p=0.9106). EFS results were consistent across all prespecified patient subgroups. In terms of secondary endpoints, there was no significant difference in high-grade recurrence-free survival between study arms (HR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.73–1.55; p=0.7658) and no impact of atezolizumab on OS (HR: 1.73; p=0.1799). The safety profile of the treatment combination was consistent with that of the individual agents. However, atezolizumab plus BCG showed higher rates of treatment-related AEs (TRAE; 94.1% versus 75.6%) and Grade ≥3 TRAEs (22.7% versus 8.8%) compared to BCG alone.19,20

In contrast to positive results from the POTOMAC study, this Phase III trial in BCG-naïve patients with high-risk NMIBC did not demonstrate an EFS advantage from the addition of atezolizumab to 1-year BCG therapy. The ALBAN trial authors therefore concluded that the benefit from checkpoint inhibitor plus BCG therapy may be context- and agent-specific, rather than a class effect.19,20

How Did POTOMAC and ALBAN Diverge?

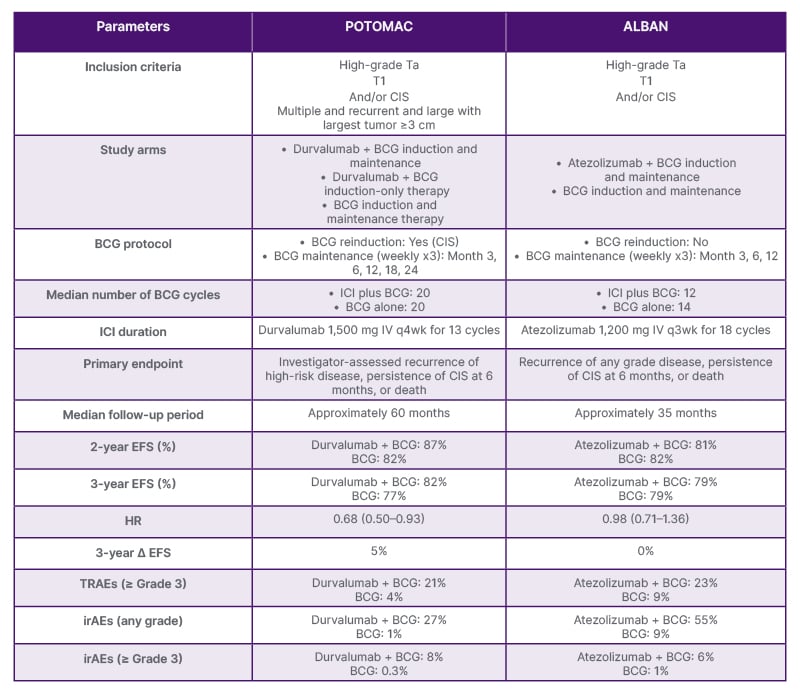

Table 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of some of the key study design features and efficacy/safety outcomes from the POTOMAC and ALBAN trials. Unlike POTOMAC, ALBAN did not show an improvement in EFS with immunotherapy plus BCG versus BCG alone.11,12,19-21 This raises questions about the potential impact of agent selection, dosing, route, and timing of immunotherapy administration, as well as patient selection, in influencing clinical outcomes.

Table 1: Compare and contrast: POTOMAC and ALBAN.11,12,19-21

BCG: Bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CIS: carcinoma in situ; EFS: event-free survival; HR: hazard ratio; ICI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; irAE: immune-related adverse event; IV: intravenous; q3wk: every 3 weeks; q4wk: every 4 weeks; TRAE: treatment-related adverse event.

The eligibility criteria for POTOMAC and ALBAN were similar, with both trials enrolling patients with NMIBC with high grade Ta, T1, and/or CIS. However, POTOMAC also allowed patients with multiple, recurrent, large tumors (≥3 cm) to participate. In terms of baseline patient characteristics, those in the ALBAN trial had a higher percentage of CIS overall, but a lower percentage of pure CIS. The proportion of patients with T1 and Ta was also lower in ALBAN than in POTOMAC, and only 7/112 patients had persistent CIS as an event. The presence of CIS represents a very heterogeneous patient population, and persistent CIS did not appear to be a driver of EFS in these studies.11,12,19-21

Differences are also evident in other aspects of the POTOMAC and ALBAN trial designs. In order to evaluate if immunotherapy could replace BCG maintenance, POTOMAC had a BCG-induction-only arm, whereas ALBAN did not. For the primary endpoint, POTOMAC employed investigator-assessed DFS, defined as the time from randomization until first recurrence of high-risk disease or death, while ALBAN relied on investigator-assessed recurrence of any grade disease. The pragmatic EFS endpoint used in the ALBAN study was therefore a key differentiator versus POTOMAC, and may have diluted any potential signal. Although the duration of immunotherapy in both trials was similar (approximately 1 year), patients in the ALBAN study received a lower median number of BCG cycles compared to POTOMAC.11,12,19-21

Collectively, these factors, most notably the lower-risk patient population and shorter BCG duration, may help to explain the differences in outcomes between the POTOMAC and ALBAN trials. The longer median follow-up in POTOMAC than ALBAN (>5 years versus approximately 3 years, respectively) is also clinically important to elucidate the long-term effects of immunotherapy on DFS in NMIBC.11,12,19-21

The View Through a Practice Lens

“Is the use of systemic treatment for NMIBC clinical precision or overreaction?” asked Bradley McGregor from the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, USA. This discussant session at ESMO 2025 drilled deeper into the results of the POTOMAC and ALBAN studies and considered some of the key clinical practice implications.21

As McGregor pointed out, outcomes with modern TURBT and BCG are markedly superior to those seen in the original SWOG study, which was conducted over 25 years ago and is frequently cited to support BCG failure rates between 30–40% in high-risk NMIBC.22 The 5-year DFS in patients who had no disease at 3 months was 60% in the SWOG-8507 study. In current practice, 3-year EFS rates stand at around 75% or more among all patients with high-risk NMIBC given BCG.21 It is against this backdrop that the POTOMAC trial showed clear benefit from the addition of immune checkpoint blockade to BCG, eliciting around a 5% improvement in EFS at 3 years.11,12,21 Another well-conducted Phase III clinical trial, the CREST study, has also shown a clear improvement in EFS with the addition of immunotherapy to 2 years of BCG therapy. In the CREST trial, the anti-PD1 antibody sasanlimab significantly improved EFS (HR: 0.68; p=0.0095) versus BCG alone in patients with BCG-naïve, high-risk NMIBC.23

The biological rationale for pairing BCG with immune checkpoint blockade lies in the observation that PD-L1 expression is increased in patients who are BCG-resistant.24,25 Combining BCG with systemic immunotherapy earlier in the treatment pathway for NMIBC may therefore help to improve long-term outcomes.21 For patients failing on BCG therapy, current NMIBC management guidelines unanimously recommend radical cystectomy, which further highlights the need to invest in therapies beyond BCG.4,5

Patient selection is vitally important when considering patients with BCG-naïve, high-risk NMIBC for potential checkpoint inhibitor therapy. McGregor cautioned against generalizing early immunotherapy to all high-risk, BCG-naïve patients, and emphasized the need for biomarker-driven treatment selection moving forward. The improvement in DFS with immunotherapy plus BCG must also be balanced against toxicity. Grade ≥3 TRAEs occurred in 21% of patients in the POTOMAC study and 23% in the ALBAN trial, although the rate of Grade ≥3 irAEs was markedly lower (8% and 6%, respectively). This toxicity profile is manageable but non-negligible in a population with otherwise excellent oncological outcomes under optimized TURBT + BCG alone, and must therefore be factored into shared-decision making with patients to balance the desire for bladder preservation against potential AEs.21

The optimal duration of BCG maintenance is another important practice-oriented consideration. Rouprêt noted, in particular, that 1 year of BCG maintenance appears insufficient in the context of combined strategies and that, taken together, ALBAN, POTOMAC, and CREST do not support BCG de-escalation when adding immunotherapy. On the contrary, longer maintenance schedules seem critical to optimize outcomes.

Finally, it is also important to consider healthcare system realities and the capacity of urology-led clinics to operationalize systemic immunotherapy safely within their workflow. Key real-world practical considerations include the logistical capacity to infuse drugs and strategies for management of potential irAEs. Surveillance costs and the additional burden imposed by treatment administration and monitoring also need to be considered. To safely and practically implement systemic immunotherapy alongside BCG in the clinical practice setting, multidisciplinary collaboration and close coordination between urology and oncology will therefore be vital.21

Looking to the Horizon

The pace of clinical development across the entire bladder cancer space, and NMIBC in particular, is continuing to accelerate. Other notable presentations on NMIBC at ESMO 2025 included the INTerpath-011 Phase II trial of intismeran autogene (V940/mRNA-4157) plus BCG versus BCG alone for high-risk NMIBC, and efficacy and safety results from Formula-01, a Phase II trial of disitamab vedotin plus BCG in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) high-expression, high-risk NMIBC.25,26 Also disclosed were results from the SunRISe-1 study showing an association of molecular markers with clinical response in patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC and CIS undergoing treatment with TAR-200 (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA). TAR-200 is an investigational, targeted drug-releasing device that slowly releases gemcitabine directly into the bladder.27

Also in the BCG-unresponsive setting, the FDA has recently approved nogapendekin alfa inbakicept-pmln (N-803) for patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC CIS with or without Ta or T1 disease.28 Nogapendekin alfa is an IL-15 superagonist that stimulates proliferation of both natural killer and T cells, thereby boosting the immunological response from BCG or other checkpoint inhibitors.28 Its approval is based on positive findings from clinical studies, including QUILT 3.032, which showed approximately 70% CR rates and approximately 90% cystectomy avoidance in patients who had not responded to other therapies.29,30

Multiple clinical trials are ongoing in the NMIBC space exploring different treatment approaches for patients with intermediate and high-risk disease, including those with BCG-unresponsive disease.31 Results from the BRIDGE trial assessing the regimen of intravesical gemcitabine plus docetaxel versus BCG in high-risk NMIBC, in particular, are awaited.32

In the area of immunotherapy plus BCG combination therapy, there is also more work to do to build on the positive findings from the POTOMAC trial. In particular, the effect of systemic immunotherapy plus BCG combinations on cystectomy-free survival, and any correlation with improvements in EFS, remain unknown at this stage.21

Moving forward, renewed focus on biomarkers will be vital to identify those patients with high-risk NMIBC most likely to benefit from systemic immunotherapy plus BCG and other bladder-sparing strategies. Biomarker developments, including advances in AI-based biomarkers, were key themes at ESMO 2025.31 In the bladder cancer arena specifically, encouraging results were presented supporting the use of circulating tumor DNA-guided therapy in muscle-invasive disease.33

Conclusion

The presentation of results from the POTOMAC and ALBAN trials were key highlights in NMIBC at the ESMO Congress 2025, and provided important insights into the role of systemic immunotherapy in the treatment of high-risk, BCG-naïve disease. In the POTOMAC trial, adding 1 year of durvalumab to BCG induction and maintenance demonstrated a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in DFS, reducing the risk of disease recurrence or death by 32%, in patients with BCG-naïve, high-risk NMIBC compared to BCG alone.

BCG has long been the cornerstone of NMIBC therapy, and the POTOMAC study provides Phase III evidence to support a potential shift toward earlier use of systemic immunotherapy in selected patients with high-risk disease, alongside BCG. Future research should prioritize biomarker-based patient selection and refinement of the timing, duration, and delivery route for immunotherapy in order to optimize outcomes for patients with high-risk NMIBC.