Meeting Summary

During this symposium at the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2025, leading experts in oncology and nutrition discussed state-of-the-art nutritional strategies aimed at optimising clinical outcomes and quality of life (QoL) for patients with cancer. Chairperson Florian Scotté, Gustave Roussy Institute and Université Paris Saclay, France, opened the session by emphasising that, as cancer survival improves, QoL has become a key outcome, making supportive care (including nutrition) an essential component of comprehensive oncology care. The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying malnutrition and cancer-associated wasting were then explored by Jann Arends, University of Freiburg, Germany, highlighting their impact on treatment response, survival, and QoL. Alessandro Laviano, Sapienza University, Rome, Italy, reviewed current and emerging therapeutic approaches for malnutrition and cachexia management, focusing on the latest guideline recommendations and stressing the need for early multimodal interventions combining nutrition, physical activity, and pharmacological support. Strategies to overcome anabolic resistance and enhance nutrient balance were then presented by Paula Ravasco, Catholic University in Lisbon, Portugal, who emphasised the importance of adequate dietary intake and tailored counselling. Finally, Riccardo Caccialanza, University of Milan; and Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy, summarised the robust clinical evidence supporting immunonutrition in surgical oncology and its emerging applications in systemic treatment.

Introduction: The Foundation of Nutritional Oncology

Due to major advances in anticancer therapies, many patients now live longer with cancer as a chronic disease, making QoL a key care priority, Scotté explained. The success of oncology care increasingly depends on the quality of supportive care, which includes pain, psychological, and nutritional management, as defined by the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC).

Both prehabilitation and rehabilitation are crucial to optimise patients’ functional status and QoL during and after treatment. Prehabilitation, in particular, can help patients better tolerate the toxicity of anticancer therapies and mitigate the adverse effects of malnutrition, he emphasised.1,2 Global publication trends show that both sarcopenia and malnutrition have become major research focuses in modern oncology.3 There is also increasing evidence supporting the importance of adopting a multidisciplinary approach to sarcopenia management, using specialist tools and involving experts in nutrition, exercise, and pharmacological care.4

Evidence consistently demonstrates that low muscle mass is linked to increased dose-limiting toxicity from anticancer therapy and a higher likelihood of treatment discontinuation.5-7 Weight loss and malnutrition also negatively impact overall survival (OS), stressed Scotté, as shown in several recent studies. In a longitudinal analysis of 1,406 patients with incurable cancer, the severity of malnutrition, graded by a combination of weight loss and BMI, was associated with reduced OS.8 This link between sarcopenia and increased rates of both all-cause and cancer-specific mortality was further confirmed in a recent study involving over 1,000 patients with cancer.9 Similarly, a meta-analysis of 100 studies demonstrated an association between lean mass/sarcopenia and mortality across a range of cancer types.10

Scotté highlighted a recent analysis presented at this year’s ESMO Congress that analysed five different cachexia indicators: skeletal muscle index, weight loss, modified Glasgow prognostic score, loss of appetite, and level of growth differentiation factor (GDF)-15 (cut-off of 2,320 pg/mL). An increased number of these cachexia-related factors was associated with reduced OS in patients with solid cancer.11 Data from Nutrition Day 2024 (unpublished) confirmed the significantly greater impact of malnutrition on cohorts of patients with cancer versus patients without cancer, with an associated increase in 30-day mortality and hospital readmission rates.

Collectively, this evidence underscores the importance of early screening for malnutrition at diagnosis and throughout treatment, Scotté stressed. Cancer-related malnutrition affects not only individual patients but also the healthcare system, leading to more postoperative complications and infections, longer hospital stays, greater readmissions, and increased hospital costs.12-20 Results from a survey of over 700 individuals with a broad range of tumours have also highlighted the importance of nutrition from a patient perspective. Overall, 83% of patients with cancer considered nutrition as important during their treatment and recovery, and 59% mentioned that the topic of nutrition should be addressed earlier.21 This highlights the need for early nutritional assessment and improved patient education.

Scotté reviewed ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines on Cancer Cachexia, which provide recommendations for evaluation and management across different clinical settings.22 He also presented the Gustave Roussy model for early assessment, integrating nutrition with global symptom management.

Scotté concluded by calling for the development of “Nutritional Oncology,” involving both cancer specialists and supportive-care professionals, and invited the clinicians to join MASCC to advance multidisciplinary practice and education in this area.

Decoding Malnutrition and Cancer-Associated Wasting: Understanding the Clinical Landscape

Arends began by highlighting the high prevalence of nutrition-impact symptoms in patients with cancer, which include anorexia, nausea, dysphagia, and diarrhoea.23 These problems may be associated with the tumour itself, anticancer treatments, or metabolic derangements. Overall, approximately 30% of patients with cancer have signs of malnutrition, with prevalence exceeding 50% in upper gastrointestinal (GI) cancers, and this has a significant impact on clinical outcomes.24 Large-scale studies, each involving more than 3,000 patients, have confirmed that malnutrition, whether defined by weight loss or Global Leadership Initiative for Malnutrition (GLIM) criteria, is consistently associated with reduced OS, regardless of cancer stage.25-29 Malnutrition is also associated with reduced tumour responsiveness to treatment and decreased QoL, Arends explained, making it “of high relevance to clinical oncology.”

Arends stressed the need to adapt nutritional care to patients’ disease stage and prognosis.22 In advanced cancer, cachexia cannot be reversed in the last weeks of life. At the end of life, care should instead focus on alleviating symptoms, avoiding invasive interventions like tube feeding or parenteral nutrition. However, for patients with a survival probability of more than a few months or weeks, regular screening and nutritional intervention are warranted.22 Arends confirmed that most guidelines on nutritional care advocate for repeated screening of patients for the risk or presence of malnutrition. This should be followed by an in-depth diagnostic assessment, including food intake, nutrition impact symptoms, weight loss, BMI, and metabolic derangements.

On the subject of diagnosis, Arends clarified that cachexia is often mistakenly equated with complete muscle wasting, which represents a very late stage of the condition. In reality, cachexia can appear much earlier and is now defined as ≥5% involuntary weight loss combined with metabolic changes such as systemic inflammation.30 He explained that there are two basic subtypes of malnutrition: starvation-type malnutrition, with normal metabolism or ketosis in response to inadequate food intake; and disease-associated malnutrition, characterised by metabolic changes, systemic inflammation, and cachexia.30 Treatment for starvation-type malnutrition involves basic support for food intake or feeding to meet energy and protein requirements. In contrast, Arends stressed that management of disease-associated malnutrition remains “a major unsolved problem.” These patients typically present with insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and anabolic resistance, meaning that protein provision does not elicit the expected anabolic response seen in healthy individuals. Additional challenges include anorexia, fatigue, and activated catabolism affecting multiple organs (including the heart, skeletal muscle, fat, kidney, gut, and brain), underscoring the systemic nature of this condition.

The systemic inflammation associated with disease-associated malnutrition is driven by the interaction between the immune system and malignant cells. The tumour microenvironment and surrounding stroma produce proinflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1, which spill into the circulation and act systemically. These mediators promote fat depletion and muscle wasting, signal anorexia and fatigue in the central nervous system, and trigger metabolic changes in the liver, including altered protein synthesis.31,32 Unsurprisingly, this systemic inflammation is linked to adverse clinical outcomes, with studies showing increased infection rates and reduced survival. Multicentre studies confirm that patients with malnutrition or systemic inflammation have significantly higher hazard ratios for death (up to threefold compared to those without inflammation) and poorer survival even in early-stage or palliative settings.33-35

Arends added that other issues in patients with advanced cancer can also interfere with food intake, such as chronic pain, depression, psychological distress, and social barriers. To address these, a multidisciplinary approach is crucial, involving nurses, psychologists, social workers, oncologists, palliative care/rehabilitation specialists, and dietitians/nutritionists.22

In conclusion, Arends emphasised the importance of early screening for malnutrition and supporting with food intake/feeding when metabolism is normal. For patients with systemic inflammation or complex issues interfering with intake, multiprofessional care should be initiated. At the end of life, the focus should remain on symptomatic care only.

Breaking the Cycle: Therapeutic Strategies for Malnutrition and Muscle Wasting

“We have learned a lot about cachexia since the original consensus definition was published in 2011,” noted Laviano.36 Cachexia is now recognised as a systemic disease, rather than merely a nutritional syndrome, associated with immune suppression and complex changes across multiple organ systems, including the brain, liver, and gut microbiota.37

Cachexia is highly prevalent, although the true incidence depends on how it is defined. In the TRACERx lung-cancer study, 29% of patients met muscle loss criteria for cachexia, while over half (51%) showed changes in body composition. Notably, these changes in body composition were associated with worse cancer-specific survival outcomes.38

Beyond survival, QoL remains a critical but often overlooked dimension in cancer treatment. According to a recent analysis, only 10% of studies supporting the approval of new oncology drugs considered QoL as an outcome.39 Global QoL is closely linked to cachexia, and evidence shows that patients with poor QoL due to nutritional impairment at the start of their clinical journey rarely improve.40,41 This highlights a major gap in care: extending survival without preserving QoL is not enough. If patients live 6 more months, but spend 3 or 4 months bedridden and dependent, something is missing, Laviano commented. Oncology care must therefore aim not only to maximise efficacy and minimise toxicity but also to maintain patients’ functional independence and wellbeing.

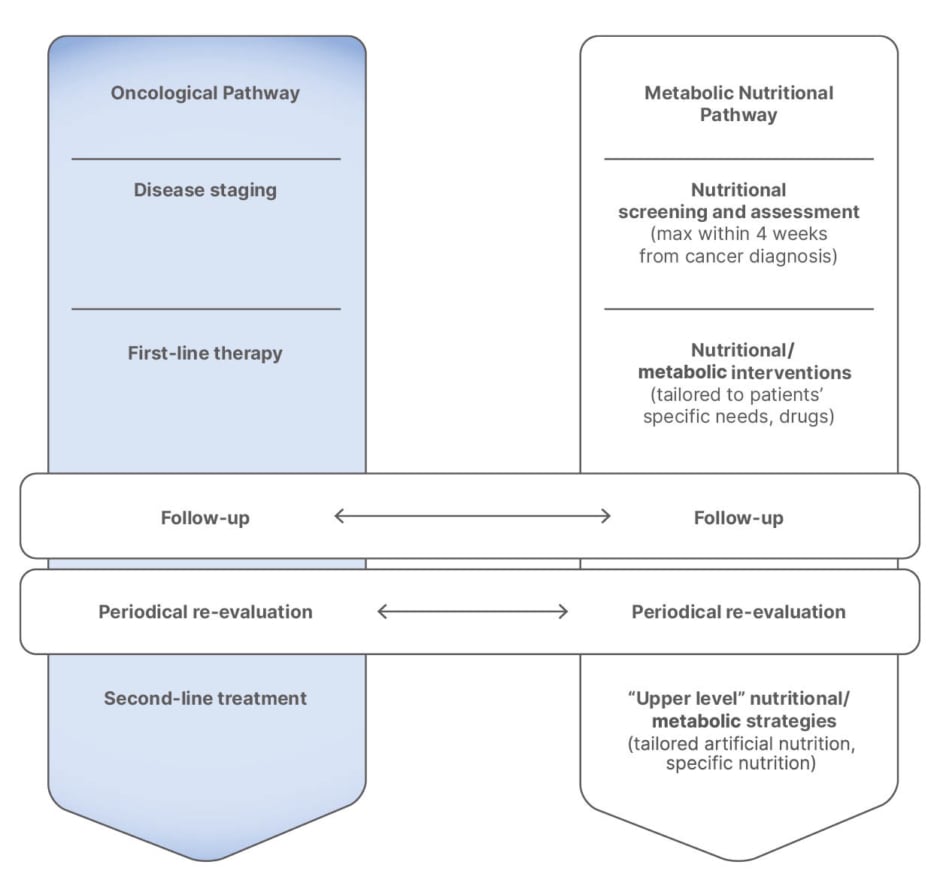

Encouragingly, results from a recent study in colorectal cancer indicate that patients with low muscle mass at the outset of their clinical journey, who are able to improve muscle mass, can achieve a survival curve similar to those without adverse body composition changes.42 To achieve these improvements, Laviano highlighted the importance of adopting a parallel approach in which the oncological pathway is closely aligned with the metabolic nutritional pathway throughout the clinical journey (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Integrating nutrition and oncology.6

A recent study described a potential genetic predisposition to cachexia development or resistance in skeletal human muscle, characterised by different molecular subtypes.43 Although genetic predisposition may play a role, current strategies must focus on preventable and treatable factors.44 Nutritional intervention remains vital and should address energy and protein requirements alongside key nutrients such as amino acids and derivatives, omega-3 fatty acids, and vitamin D. For patients with poor calorie and protein intake, tools such as dietary counselling, nutritional supplements, and enteral or parenteral nutrition are recommended by the ESMO guidelines.22 As highlighted by other speakers, multimodal intervention encompassing nutritional, exercise, pharmaceutical, and psychosocial aspects is also key.

Timing of treatment is another critical factor influencing cachexia development and clinical outcomes. A recent study from Japan showed a substantial increase in cachexia prevalence from 34% to 50% in the 1-month period between suspicion of cancer and final diagnosis, underscoring the need for early intervention.45 In the EFFORT prospective randomised trial, early screening for malnutrition and provision of nutritional support reduced 30-day mortality risk by 43% across different types of cancers.46 Exercise and physical activity have also been linked to improved disease-free survival in patients with colorectal cancer.47 However, Laviano explained that anabolic resistance can counteract these positive interventions. For example, secondary analysis of the EFFORT trial revealed that higher baseline inflammation, as measured by C-reactive protein levels, was associated with lower clinical benefit from nutritional support.48

For the specific treatment of anorexia, olanzapine has shown clinical benefits.49 Pharmacological approaches to cachexia are also under development, including anti-GDF-15 antibody (ponsegromab), anti-IL monoclonal antibody (tocilizumab), and anti-senescence-associated secretory phenotype combination therapies (quercetin and dasatinib).37

In summary, malnutrition in patients with cancer is a complex condition contributing to poor outcomes. The key message is that cachexia and malnutrition are both preventable and treatable, provided that intervention begins early. Early diagnosis is essential for meaningful results, and optimal prevention and treatment should address all contributing factors, which may evolve throughout the clinical journey.

Optimising Nutrient Balance: Strategies to Enhance Anabolism in Oncology

Low muscle mass has an adverse impact on cancer outcomes, Ravasco reiterated, including increased postoperative complications, higher chemotherapy-induced toxicity, and reduced survival.50 In the recently published LEANOX trial, chemotherapy dosing based on lean body mass was associated with a 47% lower risk of developing significant neurotoxicity and showed a trend towards improved Grade ≥2 neurotoxicity-free survival compared to standard body surface area dosing. Importantly, there was no compromise in relapse-free or OS with this muscle mass-based dosing approach.51

Muscle protein synthesis and degradation can become unbalanced in patients with cancer due to anabolic resistance. Anabolic resistance describes a decline in muscle responsiveness to normally robust anabolic stimuli such as protein intake and resistance exercise. It can be exacerbated by long periods of muscle disuse and is more common in older adults.52,53 “But we have a way of overcoming this anabolic resistance if we maintain an adequate stimulus with protein intake during the whole course of the journey,” she confirmed.

Individualised nutritional counselling has been shown to prevent the deterioration of nutritional status and reduce the incidence of malnutrition in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) undergoing chemo/radiotherapy.54 More recently, the PRIMe trial demonstrated the positive impact of dietary counselling on protein intake. Over half of patients in the 2.0 g/kg/day group maintained or gained muscle mass after 12 weeks of targeted nutritional intervention.55

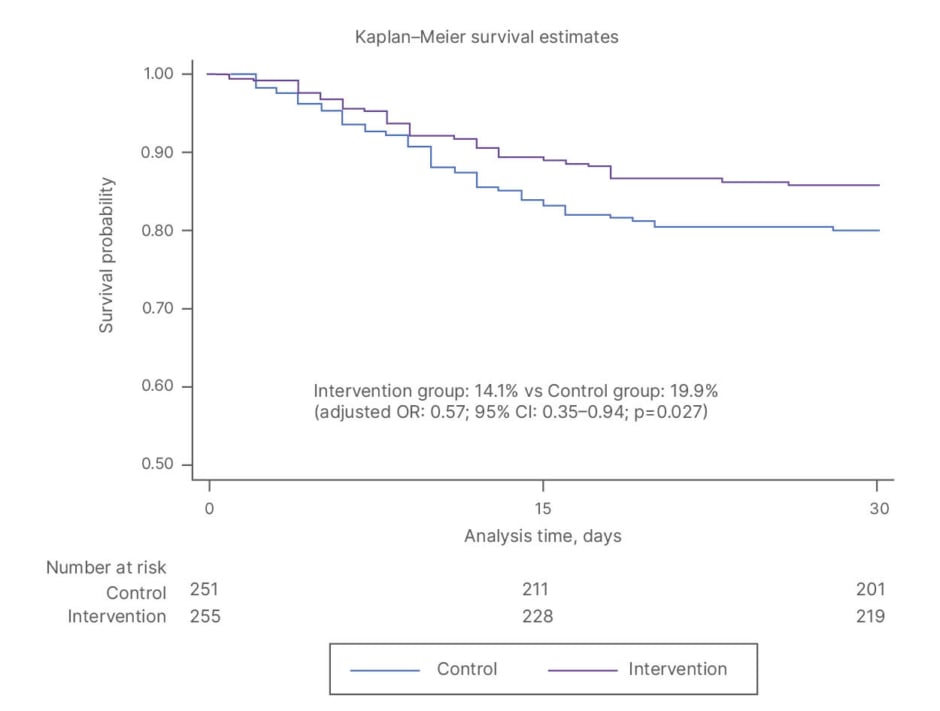

However, maintaining optimal levels of protein intake through diet alone is challenging, making oral nutritional supplements (ONS) a critical component of care. In a study comparing dietary counselling alone to counselling plus ONS, use of ONS significantly reduced interruptions and the need for changes in scheduled anticancer treatments.56 Adequate dosing of ONS is key to achieving these clinical benefits, with evidence showing that higher energy and protein intake from ONS leads to better outcomes than lower amounts.57 In the EFFORT trial, the integration of nutritional support was associated with a 43% reduction in 30-day mortality, decreased functional decline, and improved QoL (Figure 2).46

Figure 2: EFFORT trial: individualised nutrition support reduced 30-day mortality.46

OR: odds ratio; vs: versus.

In addition to protein, Ravasco highlighted omega-3 fatty acids as important nutrients that can mitigate inflammatory and catabolic responses in patients with cancer. A systematic review showed that supplementation of omega-3s favoured better recovery from weight loss and may reduce acute chemotherapy toxicity, including mucosal toxicity, peripheral neuropathy, and GI toxicity.58

Several specific protocols have been developed to aid in the implementation of nutritional therapy in routine clinical oncology practice. One example is PRONTO, which integrates European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) and ESMO guidelines and defines three checkpoints for assessing patients’ nutrition risk when starting or continuing anticancer therapy.59,60 The ESMO guideline is very explicit: every patient with cancer should undergo systematic screening and individualised nutritional assessment, considering nutritional status, symptoms, clinical history, and metabolic dysfunctions. These elements must be integrated to design a tailored intervention adapted to each patient’s needs.22

Patient compliance to nutritional intervention is critical to achieving effective results. ONSs are highly effective, especially when combined with individualised counselling. “We need to work with the patient to find common ground for greater acceptance of ONSs,” Ravasco confirmed. For example, it is important to consider loss/alterations in taste that can occur as a consequence of cancer treatment. Evidence indicates that compliance is improved when patients are offered a wide variety of flavours.60 Higher compliance has also been observed with high-energy-dense ONS (≥2 kcal/mL versus ≤1.5 kcal/mL), low volumes, and clear formulas.59-61 When oral intake is insufficient or not feasible, enteral and parenteral nutrition must be considered and integrated into the care plan to ensure adequate nutritional support.

In summary, Ravasco reiterated the importance of integrating nutritional intervention into standard oncology pathways to deliver state-of-the-art cancer care for patients.59 This approach helps maintain or restore nutritional status, improving physical function, metabolic health, and QoL. Adequate nutrition corrects macro and micronutrient deficits, reduces the frequency and duration of treatment interruptions, and lowers rehospitalisation rates, Ravasco confirmed. Stimulation of physical activity is also essential to reverse frailty and reduce disability. Ultimately, these interventions will help to achieve the ultimate goal, which is increasing patient survival, she concluded.

Navigating Immunonutrition: Established Foundations and New Frontiers

As in the wider oncology setting, Caccialanza emphasised that nutritional status impacts postoperative outcomes in cancer surgery, including survival and QoL. Malnutrition also imposes a significant economic burden: every 1 USD invested in nutrition therapy for hospitalised patients can save over 50 USD in hospital costs.62

However, nutrition is not just calories and protein. A new concept, immunonutrition, has emerged, defined as the modulation of immune system activity or its consequences through nutrients or specific food components provided in amounts above those normally consumed in the diet.63 The effectiveness of immunonutrition in oncological surgery is supported by a robust evidence base of over 100 RCTs and 62 meta-analyses across multiple cancer types. As a result, perioperative immunonutrition is now included in prehabilitation programmes and protocols, including the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol, as metabolic preparation for surgical stress. The recently updated ERAS guidelines recommend pre- and postoperative immunonutrition, including arginine, omega-3 fatty acids, and nucleotides, for all patients undergoing colorectal surgery, not just those who are malnourished.64 Similarly, ESPEN guidelines recommend immunonutrition for patients undergoing major tumour surgery and those with GI cancers.65 In a step towards implementing this evidence in the real-world setting, Caccialanza and colleagues in Lombardy, Italy, created a Clinical Nutrition Network. This initiative aims to overcome inequalities in nutritional care management by making nutritional screening mandatory in all hospitals. One of the key targets is to provide immunonutrition to at least 70% of patients with cancer.

Caccialanza reviewed extensive evidence demonstrating that immunonutrition reduces the length of hospital stay for patients with cancer.66 Recent data indicate reductions over 2 days for colorectal cancer, 3 days for oral cancer, and nearly 2 days for gastric cancer.67-73 These reductions translate into millions of EUR in potential cost-savings, he stressed. Few studies have been undertaken in bladder cancer, but preliminary case-series data on the use of immunonutrition in radical cystectomy are promising, and randomised trials are ongoing.74,75

Beyond the surgical setting, Caccialanza described immunonutrition in systemic treatment as “the new frontier.” Immunonutrition modulates the tumour microenvironment towards a cytotoxic profile, reducing inflammation (a key driver of cachexia) and enhancing immune system activation to counteract neoplastic growth.76-78 Bibliometric analysis has shown that immunonutrition during hospitalisation can reduce mortality and improve QoL in patients with cancer.79

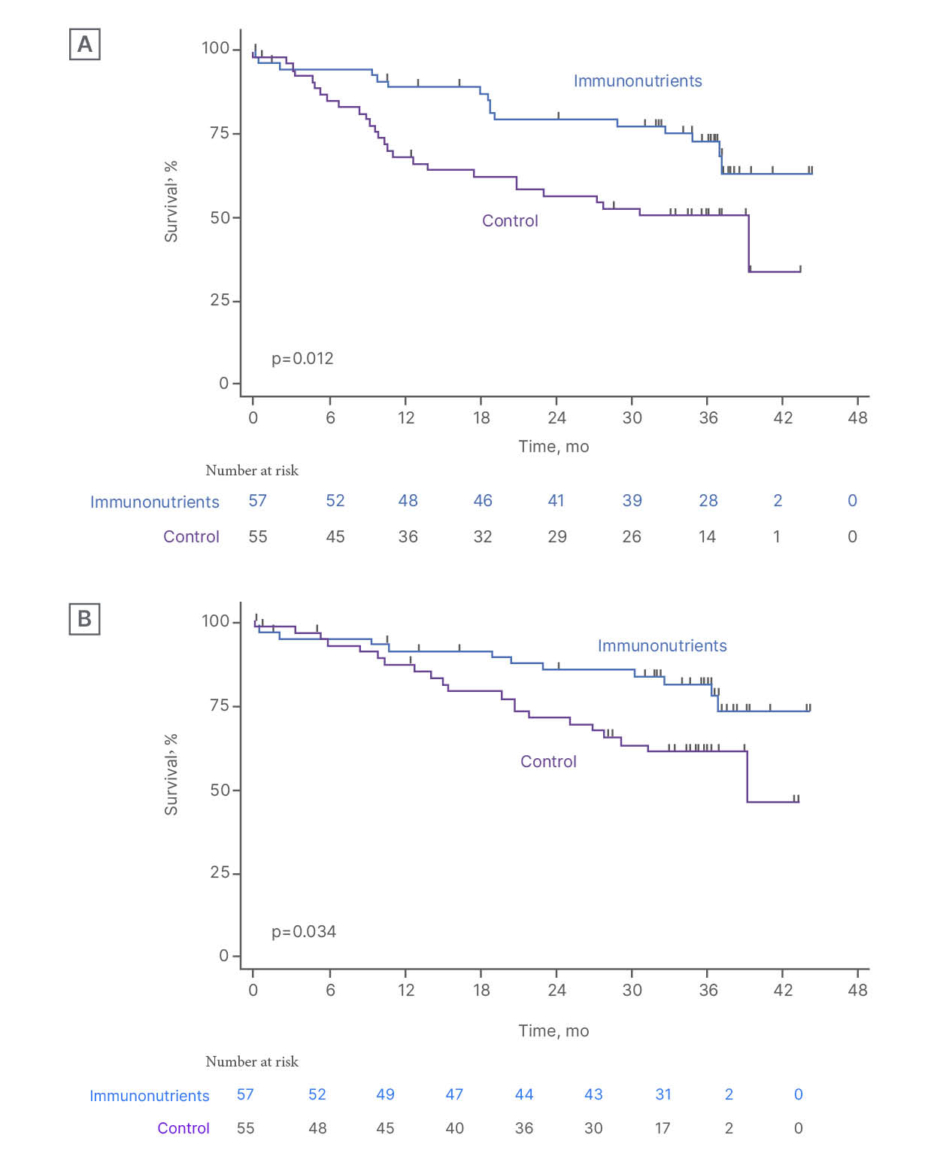

Immunonutrition may also act as a potential enhancer of systemic therapies through immune-inflammatory modulation. Small studies have shown improvements in inflammatory markers and immune responses in patients with HNSCC undergoing radiochemotherapy.80,81 The larger Phase 3 double-blind IMPATOX trial evaluated the impact of immunomodulating nutritional formula in patients with HNSCC receiving adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Although immunonutrition did not reduce severe mucositis (primary endpoint), compliant patients showed improved long-term survival (Figure 3).82

Figure 3: The IMPATOX trial.82

A) PFS and B) OS according to study treatment in compliant patients (compliance ≥75%).

mo: months; OS: overall survival; PFS: progression-free survival.

However, patients in the IMPATOX study did not receive nutritional counselling, which is a key limitation, Caccialanza noted.83 To address this, two new studies are ongoing. The first is an RCT comparing nutritional counselling plus immunonutrition ONS versus counselling plus isocaloric/isonitrogenous ONS in patients with HNSCC undergoing chemoradiotherapy. The primary endpoint is toxicity. The second trial is a multicentre, randomised, open-label, Phase 2 study evaluating immunonutrition in improving immunotherapy efficacy in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Patients will receive counselling plus immunonutrition ONS or counselling alone.84,85 Preliminary trials have shown positive results in survival and chemotherapy completion rates in patients receiving immunonutrition plus systemic anticancer therapy.86-88

Future directions may include combining immunotherapy with immunonutrition and exploring interactions with the gut microbiome, Caccialanza suggested.89,90 Hopefully, in the next few years, there will be a clear idea of the real effectiveness of immunonutrition in patients with cancer during systemic treatment, from both a clinical and economic point of view, he concluded.