Meeting Summary

This symposium took place during the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2025 in Berlin, Germany. The aim of the symposium was to discuss strategic treatment sequencing and novel second-line and beyond (2L+) approaches for patients with oestrogen-receptor-positive (ER+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative (HER2-) advanced/metastatic breast cancer (a/mBC) after first-line (1L) treatment with endocrine therapy (ET) plus inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 (CDK4/6i). Tiffany Traina from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA, described evolving standards in 2L+ ER+/HER2- mBC, including standard of care (SOC); primary and secondary endocrine resistance, emphasising that most patients with mBC will eventually develop resistance to ET; and ESMO guidelines for ER+/HER2- mBC, which are directed by endocrine sensitivity status and biomarkers. Sherko Kümmel from the Interdisciplinary Breast Unit, Kliniken Essen-Mitte, Germany, presented recommendations and strategies for treating ET-eligible patients after 1L ET plus CDK4/6i, including data from the EMERALD approval study with the selective oestrogen receptor degrader (SERD) elacestrant in patients with ESR1 mutations, and results for studies of the SERDs vepdegestrant, imlunestrant, and camizestrant. Frederik Marmé from University Hospital Mannheim and Medical Faculty Mannheim of Heidelberg University, Germany, discussed making biomarker-driven treatment decisions, including identifying mutations to drive therapeutic choices in mBC, the characteristics of ESR1 mutations, and the importance of timely ESR1 mutation testing at each progression during metastatic treatment, ideally by analysing circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) from a liquid biopsy.

Evolving Standards in Second- or Later-Line Oestrogen-Receptor Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer

Tiffany Traina

Standard of Care for Oestrogen-Receptor Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer

Approximately 70% of breast cancers are subtype hormone-receptor-positive (HR+)/HER2-, with an age-adjusted rate of 91.3 new cases per 100,000 females, based on USA data from 2018–2022.1 The standard of care 1L treatment for ER+/HER2- mBC is ET, including aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole, exemestane, letrozole), or the SERD fulvestrant, with CDK4/6i (palbociclib, ribociclib, abemaciclib).2-5 According to real-world data, approximately 90% of patients remain on 1L ET plus CDK4/6i therapy beyond 6 months, with 70–90% continuing past 12 months,6,7 and 50–70% on treatment for at least 18 months.6 ET alone in the 1L setting is reserved for select patients with specific comorbidities or a performance status that precludes the use of CDK4/6i combinations.3

Primary and Secondary Endocrine Resistance

Traina discussed the importance of differentiating patients with mBC who are resistant to ET early in their treatment journey (primary endocrine resistance) from those in whom resistance develops under selective pressure when targeting the ER with ET in an oestrogen-deprived environment (secondaryendocrine resistance).

Eligibility for ET can be classified using clinical variables.3,4,9,10 Patients who progress within 6 months of starting 1L ET-based treatment with or without CDK4/6i are considered to have primary endocrine resistance, and are usually not eligible for ET.9 Those who progress after at least 6 months of 1L ET, or any duration of response on 2L+ ET-based treatment, are considered to have secondary endocrine resistance and are eligible for ET-based regimens.9 Traina advocated for leveraging ETs in patients with endocrine-sensitive tumours to maximise the duration on ET before moving patients to cytotoxic therapies.

Second-Line Endocrine Therapyand Genomic Alterations

Treatment for patients who are eligible for 2L+ ET is defined according to the presence of genomic alterations.10-12

Intrinsic alterations, also known as truncal mutations, occur early in the tumour, are present in all the tumour cells, and persist throughout the course of the tumour.13 Examples include alterations of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, BRCA1/2 mutations, RB1 loss, and TP53 alterations.11

In contrast, acquired mutations, such as ESR1 mutations, emerge under the selective pressure of the therapies used to create oestrogen deprivation, occurring in up to 50% of patients with mBC after ET.12 According to Traina, acquired mutations are increasingly likely to emerge at progression after multiple lines of ET, with longer exposures increasing the risk.

European Society for Medical Oncology Guidelines for Oestrogen-Receptor Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer

The ESMO guidelines recommend assessing clinical eligibility and mutational statusbefore initiating an ET-based treatment in patients with ER+/HER2- mBC.3,4

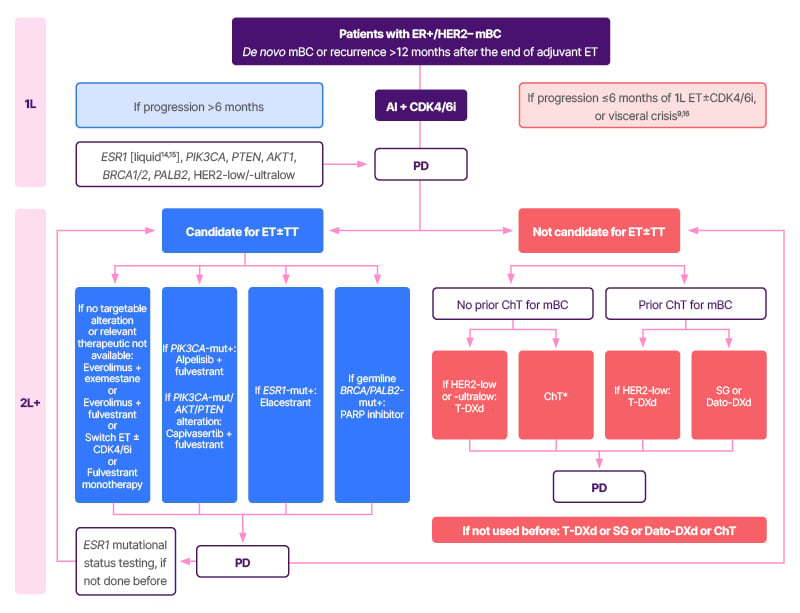

Focusing on endocrine-sensitive disease (progression after ≥6 months of ET), the guidelines emphasise the importance of biomarker testing, including liquid biopsy for ESR1 testing,14,15 to identify potential resistance to ET and guide targeted treatment (Figure 1).3,4,9,14-16

Figure 1: European Society for Medical Oncology recommendations for patients with oestrogen-receptor positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative metastatic breast cancer.3,4,9,14-16

*Taxane–bevacizumab or capecitabine–bevacizumab.

Adapted from Gennari et al.3

1L: first line; 2L+: second line and beyond; AI: aromatase inhibitor; AKT1: protein kinase B alpha; CDK4/6i: cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor; ChT: chemotherapy; Dato-DXd: datopotamab deruxtecan; ER: oestrogen receptor; ET: endocrine therapy; HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; mBC: metastatic breast cancer; mut+: mutation positive; PARP: poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; PD: progressive disease; PTEN: phosphatase and TENsin homolog; SG: sacituzumab govitecan; T-DXd: trastuzumab deruxtecan; TT: targeted therapy.

Traina highlighted, “Biomarkers help physicians to personalise treatment and provide greater opportunities for our patients. It is important to continue looking for the emergence of certain mutations, particularly ESR1 mutations, upon disease progression in the first-, second-, and later-line settings to guide treatment decisions.”

Treating Endocrine Therapy-Eligible Patients after First-Line Endocrine Therapy + Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitors

Sherko Kümmel

Patients with Metastatic BreastCancer and ESR1 Mutations:The EMERALD Study

In the EMERALD Phase III study, a total of 478 patients with ER+/HER2- a/mBC who had received one or two lines of ET (including CDK4/6i) were randomised 1:1 to elacestrant 345 mg daily (equivalent to elacestrant dihydrochloride 400 mg daily), or investigator’s choice SOC.17 Primary endocrine resistance, prior fulvestrant, and prior chemotherapy were allowed.17 Primary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with ESR1 mutations and in all patients (intention-to-treat [ITT] population).17 Approximately 70% of patients had visceral metastases, approximately 23% had received prior chemotherapy, approximately 27% had received prior fulvestrant, and approximately 40% had received two prior lines of ET for a/mBC.17

There were statistically significant and clinically meaningful results for patients with ESR1 mutations and the ITT population.17 There was a 45% reduction in risk of progression or death for elacestrant versus SOC in patients with ESR1 mutations (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.55; 95% CI: 0.39–0.77; p=0.0005), with an absolute difference of 1.9 months, versus 30% (HR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.55–0.88; p=0.0018) and 0.9 months, respectively, in the ITT population.17

PFS was improved in patients with ESR1 mutations who had no prior exposure to chemotherapy: median PFS (mPFS) was 5.3 months with elacestrant versus 1.9 months for SOC (absolute difference: 3.4 months; HR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.36–0.80; p=0.002).18

Considering the vast majority of patients are exposed to at least 12 months of prior ET plus CDK4/6i, for those with ESR1 mutations and retained endocrine-sensitivity, mPFS was 8.6 months for elacestrant versus 1.9 months for SOC (absolute difference: 6.7 months; HR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.26–0.63).19 This benefit was consistent across different subgroups: mPFS was 7.3 months in patients with liver and/or lung metastases (HR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.21–0.59), and 5.5 months in those with ESR1- and PIK3CA-mutated tumours (HR: 0.42; 95% CI: 0.18–0.94).19

Kümmel highlighted that, in patients with co-existing ESR1 and PIK3CA mutations, elacestrant was associated with a longer PFS compared with SOC (5.5 versus 1.9 months) despite 89% of the ESR1 mutations having a lower variant allele frequency compared with PIK3CA.19 This suggests that the ESR1 mutation is a main driver of disease progression, even in the context of higher variant allele frequency of PIK3CA mutations.

There were no new toxicities with elacestrant in the EMERALD study.19 The most common adverse events (all grades) in the elacestrant group were nausea (35%), fatigue (26%), and vomiting (19%).19 No patients experienced Grade 4 nausea or vomiting with elacestrant, and treatment-related adverse events led to discontinuation in 3.4% of patients (0.9% in the SOC group).19 There were no haematological safety signals and no reports of sinus bradycardia.19

Elacestrant is the first oral SERD approved in patients with ER+/HER2- a/mBC with ESR1 mutations, based on these EMERALD study data.20,21

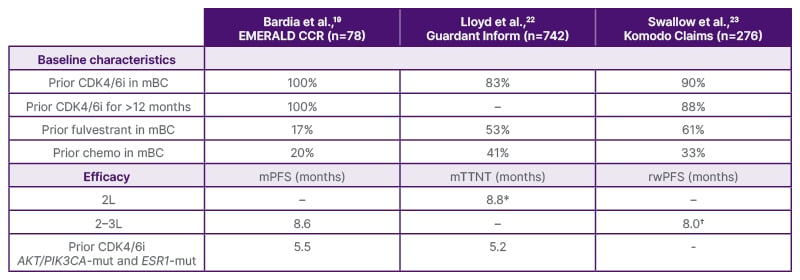

Real-world insights are valuable for affirming the efficacy benefit of elacestrant in current clinical practice. In an independent study in patients with HR+/HER2- aBC, the median real-world time to next treatment (a surrogate for PFS) was 8.8 months (95% CI: 4.8–not reached) and 5.9 months (95% CI: 4.6–10.6) for patients who had one and two prior lines of treatment, respectively.22 In a company-sponsored retrospective analysis of elacestrant in patients with ER+/HER2- aBC and one or two prior lines of ET, median real-world PFS was 8.0 months (95% CI: 5.5–not reached).23 These results are consistent with data from the EMERALD study subgroup analysis in patients with prior ET and CDK4/6i (mPFS: 8.6 months; Table 1), as the majority of patients are treated with longer periods of prior ET plus CDK4/6i.19,22,23

Table 1: Elacestrant data from EMERALD19 and real-world studies.22,23

*In 104 patients who received elacestrant in 2L.

†In 166 patients who received elacestrant in 2–3L.

Direct comparisons of efficacy and safety should not be made, and conclusions should not be drawn or inferred in the absence of head-to-head studies.

This was an exploratory analysis. RWE analysis results are observational in nature. There was no prespecified statistical procedure controlling for Type 1 error.

2L: second line; 3L: third line; CDK4/6i: cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor; chemo: chemotherapy; mBC: metastatic breast cancer; mPFS: median progression-free survival; mTTNT: median time to next treatment; RWE: real-world evidence; rwPFS: real-world progression-free survival.

Studies in Patients withPIK3CA Mutations

Approved treatment for ER+/HER2- mBC with PIK3CA mutations is alpelisib (a PI3Ka inhibitor) plus fulvestrant, and with PIK3CA mutations/AKT/PTEN alterations, it is capivastertib (an AKT pathway inhibitor) plus fulvestrant (Figure 1).3,4 Kümmel outlined key studies evaluating these treatments.

In the SOLAR-1 approval study in patients without prior CDK4/6i, mPFS was 11.0 months (95% CI: 7.5–14.5) for alpelisib plus fulvestrant versus 5.7 months (95% CI: 3.7–7.4) with placebo (HR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.50–0.85; p<0.001).24

The results of the BYLieve study in patients with prior CDK4/6i showed that mPFS was 8.3 months (95% CI: 5.5–10.1) for alpelisib plus fulvestrant in patients with ESR1 wild-type and 5.6 months (95% CI: 3.8–12.0) in patients with ESR1 mutations (this study had no SOC arm).25,26

In the CAPItello-291 study in patients with PIK3CA mutations/AKT/PTEN alterations, mPFS in the overall population was 7.3 months (95% CI: 5.5–9.0) with capivasertib plus fulvestrant versus 3.1 months (95% CI: 2.0–3.7) with placebo plus fulvestrant (HR: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.38–0.65; p<0.001).27 However, mPFS was shorter in patients with prior CDK4/6i (5.5 months) or prior chemotherapy (3.8 months).28

The CCTG/FINER study in patients with PIK3CA mutations/AKT/PTEN alterations showed shorter mPFS with ipatasertib (an AKT pathway inhibitor) in those with co-occurring ESR1 mutations compared with the ITT population (3.7 versus 5.3 months; placebo: 1.9 months).29

Kümmel summarised that, in tumours retaining endocrine-sensitivity and co-existing PIK3CA and ESR1 mutations, elacestrant monotherapy could be a good option before PI3K/AKT pathway inhibitors, as data indicate that elacestrant has similar efficacy, although there are no head-to-head studies, and a manageable safety profile.19,24,27,29

Focus on New Oral Selective Oestrogen Receptor Degraders: Vepdegestrant, Imlunestrant, and Camizestrant

Kümmel then turned the focus to the new oral SERDs, vepdegestrant, imlunestrant, and camizestrant.

The VERITAC-2 Phase III study of vepdegestrant (a new oral SERD known as a proteolysis-targeting chimera) versus fulvestrant excluded patients who had received prior fulvestrant or chemotherapy,30 which is in contrast to the EMERALD study.17-19 mPFS data were positive for vepdegestrant in patients with ESR1 mutations (5.0 months [95% CI: 3.7–7.4] versus 2.1 months [95% CI: 1.9–3.5]; p<0.001), but there was no statistically significant mPFS benefit in the ITT population (3.7 months [95% CI: 3.6–5.3] versus 3.6 months [95% CI: 2.2–3.8]; p=0.07).31

Prior fulvestrant or chemotherapy and primary endocrine resistance were not allowed in the EMBER-3 Phase III study of imlunestrant versus SOC or imlunestrant plus abemaciclib.32 Similar to the VERITAC-2 study, mPFS benefit was seen in patients with ESR1 mutations (mPFS: 5.5 versus 3.8 months; absolute difference: 1.7 months; HR 0.62; 95% CI: 0.46–0.82; p<0.001), but not in the all-comer population (mPFS: 5.6 versus 5.5 months; absolute difference: 0.1 months; HR: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.72–1.04; p=0.12), in this case for imlunestrant monotherapy versus SOC.32 For context, the absolute difference for the patients with no prior chemotherapy in the EMERALD study was 3.4 months.18 These studies had different patient populations.

The mPFS for imlunestrant plus abemaciclib was 9.4 months versus 5.5 months for imlunestrant alone (HR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.44–0.73; p<0.001); however, this does not appear to translate to an overall survival benefit (HR: 1.34; 95% CI: 0.81–2.21; p=0.25).32,33

Kümmel acknowledged that the EMERALD,17,19 VERITAC-2,30 and EMBER-332 studies showed mPFS benefit for oral SERDs in patients with ESR1 mutations; however, EMERALD was the only study that also showed benefit in the ITT population.17,19 Kümmel highlighted that the baseline patient characteristics differed for these studies (e.g., prior fulvestrant or chemotherapy were allowed in VERITAC-230 and EMBER-3,32 but not in EMERALD;17,19 and primary endocrine resistance was allowed in EMERALD,17,19 but not in EMBER32), and this should be taken into account when evaluating outcomes.

Kümmel rounded off his presentation with a discussion of SERENA-6, a Phase III study in patients with ER+/HER2- aBC receiving an aromatase inhibitor plus CDK4/6i for ≥6 months, who had ESR1 mutations detected in ctDNA (i.e., molecular progression) with no clinical evidence of disease progression, to see if switching to camizestrant plus CDK4/6i is beneficial compared with continuing the initial treatment.34,35

The results were statistically significant for camizestrant for the primary endpoint: median investigator-assessed PFS was 16.0 months (95% CI: 12.7–18.2) for camizestrant plus CDK4/6i and 9.2 months (95% CI: 7.2–9.5) for aromatase inhibitor plus CDK4/6i (adjusted HR: 0.44; 95% CI: 0.31–0.60; p<0.0001).34

Kümmel highlighted that the median (range) time to detection of ESR1 mutations was 22 (4–95) months in the camizestrant plus CDK4/6i group and 22 (6–96) months in the aromatase inhibitor plus CDK4/6i group, which indicates that serial liquid biopsy could be considered.34

Kümmel also noted that 46% of patients received chemotherapy at progression on camizestrant plus CDK4/6i compared with 23% at progression on aromatase inhibitor plus CDK4/6i.34

According to Kümmel, there are unanswered questions for SERENA-6, including whether this is a class effect, whether the different ctDNA platforms have an impact on detection rates and results, which patients should remain on ET-based regimens, whether this approach delays the time to chemotherapy, and whether the 9-month response in the control arm is worth giving up.

Making Biomarker-Driven Treatment Decisions

Frederik Marmé

Identifying Mutations Drives Therapeutic Decisions in Metastatic Breast Cancer

Marmé explained that mutation testing provides clinically actionable information that directly influences treatment selection and sequencing decisions in mBC. Marmé clarified that biomarker testing only has clinical utility if treatment decisions depend on the biomarker, and the challenge is to define which patients to test, which sample to take, and at what time point.

Referring to Traina’s presentation, Marmé emphasised the importance of understanding the difference between intrinsic and acquired mutations in terms of clinical utility. Marmé reiterated that intrinsic (truncal) mutations occur early during the course of the disease, and are present in a far higher proportion of tumour cells than acquired mutations, which occur at a later stage under the evolutionary pressure of treatment. Therefore, intrinsic mutations can be found earlier than acquired mutations, for example, in archival tissue or in a breast biopsy sample at the time of diagnosis of metastatic disease. Marmé emphasised that, in contrast to intrinsic mutations, acquired mutations leading to endocrine resistance in mBC can be identified at 1L disease progression (i.e., in a 1L metastatic setting).

Both intrinsic and acquired mutations help guide treatment selection in the subsequent therapy lines. The identification of intrinsic mutations, such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR alterations, enables the initiation of precision therapy using PI3K or AKT inhibitors. Acquired ESR1 mutations guide clinicians towards effective treatment approaches, including the use of the oral SERD elacestrant, as tumours become resistant to SOC endocrine-based regimens, even in the context of co-existing intrinsic mutations.

The Characteristics of ESR1 Mutations

Breast cancer is a dynamic disease in which intrinsic mutations occur early on and new mutations, such as ESR1 mutations, develop over the course of treatment (acquired mutations).3,4,36 Marmé explained that the stress of oestrogen deprivation during treatment leads tumours to evolve so that the ER functions in the absence of oestrogen; therefore, the deprivation of oestrogen no longer has an impact. This mechanism underlines ESR1 mutations; these mutations lead to a functioning ER without the presence of oestrogen and are associated with acquired resistance to treatments that rely on oestrogen deprivation, such as aromatase inhibitors.

Molecular profiles can vary between and within tumour sites, and there is a heterogeneous distribution in tissue.36,37 Marmé highlighted that ESR1 mutations are not uniformly present throughout metastases; therefore, a tissue biopsy sample from just one site may not be sufficient to detect these mutations.

Marmé summarised that ESR1 mutations are acquired, subclonal, and drive resistance to ET, emphasising that 2L+ treatment choices are defined by the eligibility to receive ET and are driven by biomarker status.3,4 Marmé added that for patients with retained endocrine sensitivity, guidelines recommend exhausting sequential ET-based regimens in 2L+ settings.3,4

Exposure to Endocrine Therapy and ESR1 Mutations

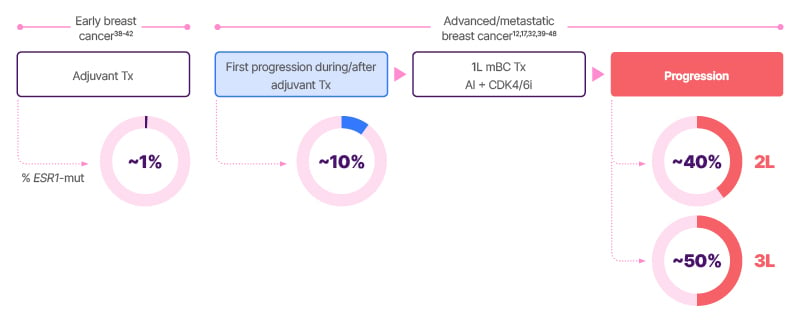

Longer exposure to ET in mBC increases the chance of developing ESR1 mutations during treatment (Figure 2).12,17,32,38-48

ESR1 mutations are infrequent (approximately 1%) in primary early breast cancer tissue, whereas in 1L metastatic disease, the rate of ESR1 mutation is approximately 10% (Figure 2). Mutation testing at progression after a prolonged period of oestrogen deprivation with 1L aromatase inhibitor plus CDK4/6i shows an ESR1 mutation rate of approximately 40% (2L), with rates of approximately 50% in the third-line setting.12,43,49 Hence, a higher incidence of ESR1 mutations is identified at disease progression. Marmé commented, “It makes sense to test for ESR1 mutations repeatedly in patients who are considered endocrine sensitive and candidates for ET. However, the sensitivity of mutation assays is limited, and we are looking for a needle in a haystack.”

Figure 2: Exposure to endocrine therapy in metastatic breast cancer and the development of ESR1 mutations.12,17,32,38-48

1L: first line; 2L: second line; 3L: third line; AI: aromatase inhibitor; CDK4/6i: cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor;

ET: endocrine therapy; mBC: metastatic breast cancer; mut: mutation; Tx: treatment.

ESR1 Mutation Testing: Tissue Versus Liquid Biopsy

The incidence rate for ESR1 mutations in biopsies from patients with mBC who progressed on 1L treatment has been reported to be 27% in tissue versus 38% in liquid biopsy, irrespective of the tumour fraction in the circulating DNA, and 57% when the tumour fraction of the circulating DNA was at least 1%.44

Marmé summarised the differences between tissue and liquid biopsy for ESR1 mutation testing as follows. Tissue biopsy has low sensitivity for ESR1 mutations, is invasive, has a long turnaround time, and may not detect all mutations, given the subclonal and heterogeneous nature of ESR1 mutations within the tumour.50-54 Archival breast tissue from the initial biopsy should not be used to identify ESR1 mutations, as these are rare (1%) in the primary tumour and are typically acquired during mBC treatment.14

In contrast, liquid biopsy has high sensitivity for ESR1 mutations, is minimally invasive, repeatable, with fast sample acquisition, and reveals tumour heterogeneity, including the presence of subclonal ESR1 mutations from all metastatic disease sites.14,50-52,55,56 Available methods to detect ESR1 mutations include next-generation sequencing (including as part of a solid tumour panel) and digital polymerase chain reaction assays.45

The Importance of Timely ESR1 Mutation Testing

The results from liquid biopsy testing for ESR1 mutations show that ctDNA tumour fraction (i.e., the proportion of circulating DNA in the blood that originates from the tumour) increases with cancer clinical stage.40,57 Marmé underscored that the likelihood of finding ESR1 mutations during stable disease is very low, and testing for these mutations should be conducted at each progression on metastatic treatment, if not detected previously, with guidelines recommending testing in ctDNA using liquid biopsy.3,4,14,15

Closing Remarks

Marmé summarised that it is important to test for biomarkers at the right time, at each progression on metastatic treatment rather than during stable disease, and testing regimens should include germline testing for BRCA and PALB2 mutations, which are “more often forgotten than ESR1 and PI3K mutations.” Kümmel remarked that the careful selection of patients for treatment based on their baseline characteristics, endocrine sensitivity, and mutation status is the key to optimising treatment outcomes in the future. Traina concluded, “It’s such an exciting time in breast oncology practice, and I’m optimistic for our patients. I think our biggest challenges are around sequencing. The trials can only take us so far, and the field is advancing at a rapid pace. We need to understand mechanisms of resistance, who needs doublets, and how we sequence all these great options.”

| Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard or search for MHRA Yellow Card in the Google Play or Apple App Store. Adverse events should also be reported to Menarini Stemline at [email protected] or on +44(0) 800-047-8675. |