Meeting Summary

These symposia were held during the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Congress 2025. The first symposium focused on the importance of looking beyond exacerbations when evaluating the burden of COPD, examined the mechanistic pathways of Type 2 inflammation that can be associated with COPD pathology, and provided an update on clinical trial data for biologics targeting Type 2 cytokines (e.g., IL-4, IL-13, IL-5). Celeste Porsbjerg, Bispebjerg Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark, discussed how COPD manifests as a vicious cycle, driven by airflow limitation, respiratory symptoms, and acute exacerbations, each of which must be addressed to more holistically improve patient outcomes. Nicola Hanania (chair), Baylor College of Medicine, Ben Taub Hospital, Houston, Texas, USA, reviewed the pathophysiology of Type 2 inflammation and how patients with this underlying inflammatory phenotype experience worse outcomes with regard to the three key contributors of COPD. Surya Bhatt, University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA, presented an overview of recent and upcoming clinical trials for biologics currently used and under investigation to treat COPD with Type 2 inflammation, highlighting key results related to exacerbations, lung function, and quality of life.

The second symposium reviewed exacerbations, lung function, and health status through the lens of disease stability in COPD, with a focus on the potential role of disease stability when considering patient treatment. Dave Singh, University of Manchester, UK, introduced the concept of disease stability and highlighted the importance of lung function as a key component of disease stability beyond exacerbation control. Klaus Rabe (chair), University of Kiel, Germany, discussed the role of exacerbation control in achieving disease stability, and explored the importance of integrating health status measures and comorbidity management into the COPD treatment framework. Both symposia concluded with a panel discussion of the concepts introduced in each respective presentation.

Less Flare, More Function: Recognising the Full Spectrum of COPD Patient Outcomes

Introduction

Nicola Hanania

Since COPD was first proposed as a group of chronic lung diseases in the 1960s, its definition and management approaches have evolved to constitute a heterogeneous lung condition with a focus on treatable traits based on distinct phenotypes.1-3 This symposium, held during the ERS Congress 2025, delved into the pathophysiology of COPD with underlying Type 2 inflammation and the use of biologics to treat this subset of patients. It also explored the importance of looking beyond exacerbations to consider the impact of airflow limitation and symptoms on the daily lives of all individuals with COPD when establishing treatment goals.

Beyond the Numbers: Unmasking the Burden of COPD

Celeste Porsbjerg

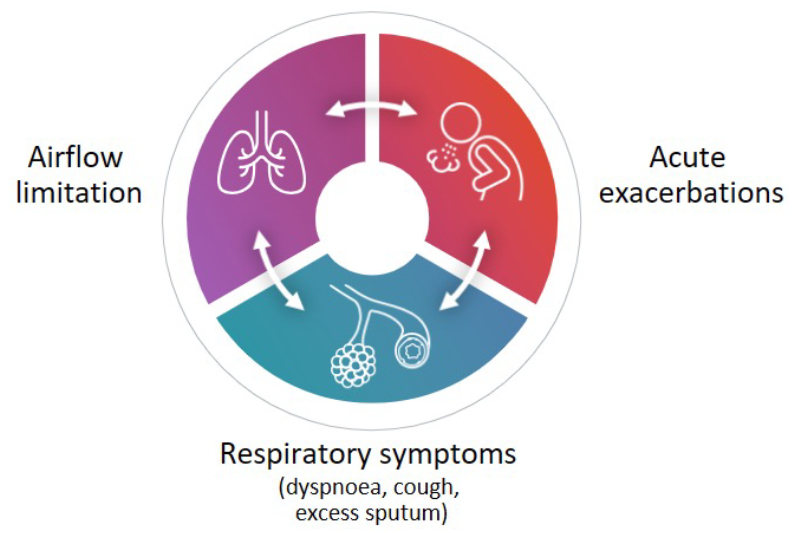

COPD has broad-reaching, substantial negative effects on the health of individuals worldwide. Responsible for 3.5 million deaths in 2021, it is the fourth leading cause of death globally according to the WHO.4 The disease is fundamentally characterised by three interconnected components: 1) persistent airflow limitation; 2) respiratory symptoms; and 3) exacerbations, each of which contributes substantially to patient burden.3 These three components together create a vicious cycle that underpins disease progression (Figure 1).3

Figure 1: The vicious cycle of COPD.2

The decrease in lung function associated with COPD is rapid and occurs regardless of whether patients experience exacerbations.5 This functional impairment begins early in the disease course and is more accelerated in the initial phases of COPD, when assessed as expiratory airflow reduction.5 These declines in lung function translate to an increased risk of adverse outcomes, including increased probability of readmission and post-discharge mortality.6,7

Patients with COPD report burdensome day-to-day symptoms such as increased coughing, dyspnoea, fatigue, and sputum production.8 Individuals with COPD report breathlessness and exhaustion that hinder their ability to do physical activities, resulting in frustration, depression, and fear.9,10 In general, patients whose symptoms occur more frequently over a 24-hour period have greater impairment in their daily activities.11

Beyond the physical manifestations, COPD profoundly impacts patients’ quality of life and mental wellbeing. As Porsbjerg highlighted, “Patients hope to be able to maintain their social network and do things they enjoy. They get isolated, they get depressed. That’s difficult to fix with a drug, so we want to get to them before it’s that complex situation. They dream to be mobile, able to walk, move around the house, travel abroad, all those things.” This underscores the critical need for timely intervention that addresses the full spectrum of patient burden.

Exacerbations, the third component of the vicious cycle of COPD, are associated with a sharp decline in lung function that does not return to baseline.12 Moreover, having even one moderate exacerbation raises the risk of continued exacerbations in individuals with COPD, and this risk increases with increasing exacerbation frequency.13 Exacerbations take a heavy toll on patients’ overall health and wellbeing, as those with increased dyspnoea scores tend to experience at least one moderate-to-severe exacerbation annually.14

Although exacerbations of any severity have clinical impact, they are often inadequately prevented.15 Indeed, it is estimated that the majority of patients who experienced ≥2 exacerbations are inadequately treated for their disease according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommendations.15 The current GOLD severity grading system is based on post facto utilisation of healthcare resources. This grading system constitutes a major limitation, contributing to substantial variability in reported COPD exacerbation outcomes.2 Furthermore, despite GOLD recommendations that systemic corticosteroid courses should not exceed 5–7 days, newly diagnosed patients with COPD may still receive oral corticosteroid episodes that exceed 10 days.16

Porsbjerg concluded her presentation by emphasising that therapeutic goals should consider reducing patient burden across respiratory symptoms, lung function decline, and exacerbations to improve clinical outcomes.2

Inside the Airways: Understanding the Role of Type 2 Inflammation

Nicola Hanania

The journey to understanding COPD has been one of continuous evolution, moving from broad definitions to highly specific biological insights. As Hanania reflected, “For many years we identified COPD as a one-size-fits-all disease. Then we tried to realise that no, not all these patients present the same way… However, in recent years, people have wanted to know more about the mechanism beyond these phenotypes. How do we actually identify the different pathways that lead to these phenotypes? And that’s when we started talking about endotypes.” This shift in perspective has been pivotal in recognising the diverse inflammatory pathways driving COPD.

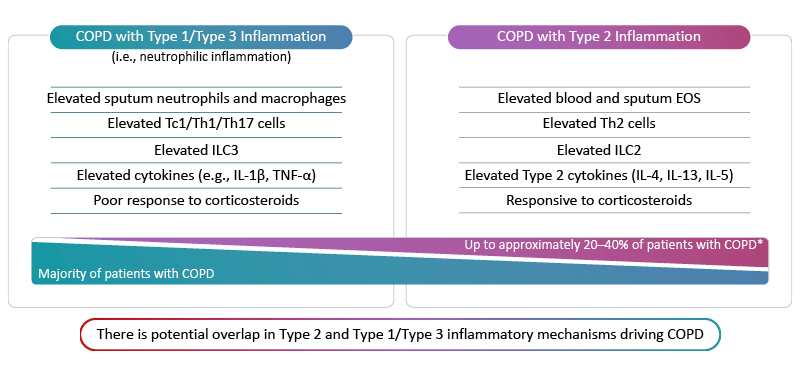

Since the introduction of blood eosinophil count (BEC) as a biomarker for predicting the efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids in preventing COPD exacerbations in 2010, our understanding of the role of inflammation in COPD pathophysiology continues to evolve.3 Whilst there is potential for overlap, Type 1/Type 3 inflammation generally drives disease in the majority of individuals with COPD, and up to about 40% of patients have COPD with Type 2 inflammation (Figure 2).17-19 COPD with Type 2 inflammation is characterised by elevations in blood and sputum eosinophils along with inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-13, and IL-5.22-23

Figure 2: Inflammatory endotypes in COPD.17-23

*Based on sputum EOS ≥3% and blood EOS ≥2%.

EOS: eosinophils; IL: interleukin; ILC: innate lymphoid cell; Tc1: Type 1 cytotoxic T cell; Th: T helper cell; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor alpha.

There is evidence that individuals whose COPD is associated with Type 2 inflammation experience worse outcomes than COPD without Type 2 inflammation. An analysis of Type 2 inflammation markers among adults with chronic airway disease participating in the Copenhagen General Population Study in Denmark found that the rate of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) decline per year over 10 years increased significantly with increasing blood eosinophils, increasing fractional exhaled nitric oxide, and both.24 Elevated blood eosinophils (≥200 cells/µL or ≥2%) in patients with COPD have been associated with an increased risk of COPD-related hospital readmission in 1 year, a decrease in time to first COPD-related readmission, and an increase in the number of COPD-related readmissions compared with patients who have lower blood eosinophils.25 Elevated blood eosinophils are also associated with an increased risk of exacerbations in individuals with COPD, with an incidence rate ratio that increases with increasing eosinophil levels.26 Blood eosinophils, therefore, may be a useful biomarker to help determine which individuals may benefit most from precision medicine strategies that target anti-inflammatory pathways.2

The Type 2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13, as well as IL-5, play several roles in the inflammatory mechanisms that culminate in the persistent symptoms, progressive lung function decline, and exacerbations experienced by patients with COPD with Type 2 inflammation. Exposure to noxious particles, bacteria, viruses, or changes in microbiome dynamics triggers the release of alarmins, resulting in Th2 differentiation and the production of these cytokines, each of which contributes to COPD pathology.27-30 IL-4 and IL-13 signalling facilitates the production and release of additional inflammatory mediators, including IgE production and B cell class switching; basophil and mast cell degranulation; and the release of leukotrienes, histamine, and prostaglandin D2.30,31 Separately, these cytokines contribute to changes in the epithelium, including fibrosis, wall thickening, and matrix metalloproteinase production, which lead to airway remodelling and play roles in alveolar destruction, airway enlargement, and barrier disruption.32-35 IL-13 and IL-4 also promote goblet cell hyperplasia and mucus production.36-38 Together, IL-4, IL-13, and IL-5 also signal eosinophil activation in bone marrow and trafficking to tissues.30,31

Understanding the mechanisms that underlie different COPD inflammatory endotypes is increasingly essential in optimising disease management for individual patients, as multiple treatments have become available or are in development that target these different cytokines. These drugs may target the alarmin thymic stromal lymphopoietin, or the Type 2 inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-13, or IL-5.39-41 Newer therapies that target underlying Type 2 inflammatory processes should aim to not only reduce exacerbations, but to help slow the cycle of lung function decline and reduce patient symptom burden.2

Biologics in Focus: New Frontiers in Treating COPD

Surya Bhatt

Currently there are two drugs that target Type 2 cytokines with positive Phase III trials: mepolizumab (licensed in the USA), and dupilumab (licensed in the USA, China, United Arab Emirates, EU, and Japan).42-48 There are no head-to-head clinical trials between these drugs, so no comparison on efficacy or safety can be made.

This new era of targeted therapies underscores a fundamental shift in COPD management, moving towards a more data-driven approach. As Bhatt articulated, “I think as we move more and more towards specific endotyping, I think we’re relying less and less on subjectivity. The more objective evidence we have, the better.” This commitment to objective evidence is crucial for identifying the right eligible patients for these advanced treatments and for accurately assessing their impact.

Mepolizumab targets IL-5 and its efficacy was initially assessed in the Phase III METREO and METREX trials, followed by the Phase III MATINEE trial.41,49 All three trials assessed the efficacy of mepolizumab compared with placebo, but only METREX and METREO data were included in the USA label for the efficacy population.49 Bhatt reviewed the data from the METREX and MATINEE studies regarding the efficacy of mepolizumab in modified intention-to- treat and intention-to-treat populations, respectively: those with blood eosinophils ≥150/µL at screening or ≥300/µL during the previous year for METREX, and those with blood eosinophils ≥300/µL at screening and ≥150/µL during the previous year for MATINEE.41,49

Dupilumab is an anti-IL-4/anti-IL-13 biologic whose efficacy was assessed in the replicate Phase III trials BOREAS and NOTUS.50 Both trials compared dupilumab 300 mg every 2 weeks with placebo.50 Bhatt reviewed data from the BOREAS and NOTUS trials and recent pooled data.40,51

The session concluded with a discussion amongst the speakers about a typical patient case over the course of 20 years of COPD, from onset of symptoms to hospitalisation.

The Knowns and Unknowns in the COPD Landscape: Concepts in Disease Stability

Pioneering Progress: Charting the Future of COPD Management

Klaus Rabe

COPD management is undergoing a paradigm shift. Over the past decade, advances in personalised medicine have expanded treatment options. A major milestone has been the introduction of biologics for patients with Type 2 inflammation who continue to exacerbate despite maximal inhaled therapy.42,44,45 These targeted options bring new opportunities but also greater complexity in defining treatment success.Rabe elaborated on the nature of this transformation, stating, “With COPD, we are entering a phase where we go away from description of damage and symptomatic benefit plus and minus steroids… We’re now coming to an era where we have drugs that address different individualised traits that you have to recognise and see in a given individual that will translate into very different aspects of the disease to someone.” This symposium asks: for these patients, are we clear on what aspects of disease we are targeting, and how should success be measured?

Defining Disease Stability: A New Framework for COPD Management

Dave Singh

Central to setting treatment goals is disease activity, the pathological processes that drive symptoms, exacerbations, and long-term progression. Importantly, these processes are considered, at least in principle, reversible, providing a framework for assessing progression from cause (e.g., activity) to consequence (e.g., damage).52,53

Lessons from other chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, asthma, and inflammatory bowel disease, show how defined targets like ‘no disease activity’ or remission can shape management strategies.52 While remission is currently an unrealistic concept for patients with COPD, particularly those with irreversible pathophysiological changes, pursuing disease stability offers a practical, positive goal: preventing further worsening and achieving each patient’s ‘personal best’, even when disease activity is low.52

Singh explained the rationale behind framing this goal as ‘disease stability’, stating, “I view this as patient language, patient-friendly language… But if you achieve these aims and you say to a patient, ‘you’re stable’, I think patients will understand that and your colleagues will understand that.” This approach aims to foster better communication and shared decision-making.

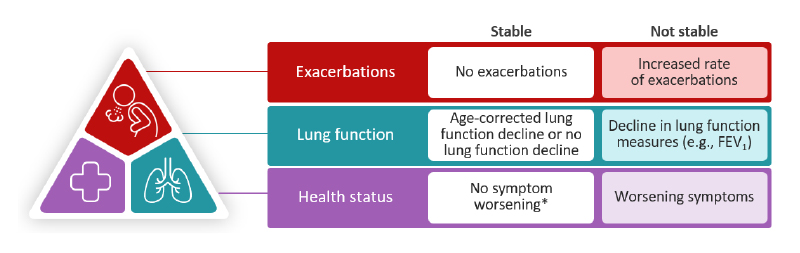

In COPD, disease stability can be conceptualised as a multi-dimensional goal, including no exacerbations, minimal lung function decline, and no worsening of symptoms (Figure 3).52 Singh further clarified this concept, emphasising, “I’m not proposing that we use some literal translation of the word ‘stable’, [or] that patients just remain the same. I’m proposing that we improve patients as much as we possibly can, get them into their optimum state that includes no exacerbations as an indicator of low disease activity, and keep them there as long as possible.”|This framework builds on the GOLD strategy and incorporates measures such as clinical control and clinically important deterioration. Optimising therapy to improve patient outcomes and then maintaining disease stability provides a structured, patient-focused approach.52 The speakers concluded the section by discussing how they frame disease stability as a goal in their discussions with patients, and how they convey the potential opportunities of biologics to achieve stable outcomes.

Figure 3: Disease stability in COPD.52

*No symptom worsening or minimal worsening that is within day-to-day variation.

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Disrupting the Cycle of Exacerbations: Where Are We Now?

Klaus Rabe

Even mild or moderate exacerbations can have a substantial impact on the clinical course of COPD. Evidence shows that a single moderate exacerbation can accelerate lung function decline, and recurrent moderate exacerbations are associated with a gradual increase in mortality risk.54,55

As exacerbations become severe, they contribute to further lung function loss; systemic effects, including increased cardiovascular risk; and higher rates of hospitalisation and mortality.2,56-58 Recognising and addressing exacerbations early is therefore critical to preserving patient outcomes.

BECs can serve as a predictive biomarker: patients with elevated BEC are more likely to experience both moderate and severe exacerbations.59 This information can inform treatment decisions, including the use of anti-Type 2 therapies or inhaled corticosteroid-containing regimens.2 This section was followed by a brief discussion between the speakers about the importance of identifying moderate exacerbations that patients may not readily report. Early recognition may allow clinicians to intervene before events escalate, supporting strategies to disrupt the cycle of exacerbations and improve long-term outcomes.

Lung Function as Part of a Composite View of Disease Stability

Dave Singh

The trajectory of lung function decline in COPD is accelerated by each subsequent exacerbation, leading to worsening quality of life and increasing clinical burden.57,58,60,61 Moderate and severe exacerbations can contribute to measurable reductions in FEV₁, highlighting the importance of early recognition and intervention.2,57,58,60-62

To assess disease stability in the context of lung function, both short- and long-term monitoring are essential. Regular spirometry, every 6–12 months in stable patients and every 3–9 months when worsening is suspected, may help to distinguish normal age-related decline from accelerated disease progression, guiding treatment adjustments.52

Lessons from other chronic inflammatory diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease, demonstrate the value of composite measures and flexible monitoring based on disease activity.52 Applying this approach to COPD, a holistic assessment of stability could combine lung function, exacerbation history, symptom burden (e.g., COPD Assessment Test [CAT™; GSK, London, UK] or modified Medical Research Council [MRC] scores), and biomarkers such as blood eosinophils. This creates a ‘personal best’ benchmark for each patient, for example, stable FEV₁, no exacerbations over 6–12 months, and consistent symptom scores, against which future changes can be measured.52 The speakers shared practical tips for how they monitor lung function in routine practice, helping to make the concept of disease stability tangible and actionable.

Health Status and Comorbidities: Addressing the Full Picture of Disease Stability

Klaus Rabe

Persistent COPD symptoms can substantially impair patients’ health-related quality of life, limiting their ability to complete everyday activities such as climbing stairs, doing heavy household chores, or shopping.2,63,64 Healthcare professionals can track this impact using tools like the CAT, the modified MRC dyspnoea scale, or the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) to quantify symptom burden and functional limitations.2,65

Beyond the impact on daily life, progression of COPD frequently leads to the development of multimorbidity, including cardiovascular disease (CVD).2 Over 80% of patients with COPD have at least one comorbid condition, and their risk of CVD is approximately twice that of patients without COPD.66,67 CVD is a leading cause of death in COPD, accounting for up to 33% of mortality, and contributes to high rates of hospital admissions.68 Considering comorbidities is therefore essential when evaluating disease stability, as they can exacerbate symptoms and complicate management. The speakers then engaged in a dialogue discussing the importance of taking a holistic view of disease stability, combining lung function, exacerbation history, symptom burden, health-related quality of life, and comorbidities to define a patient’s ‘personal best’.

The session concluded with a discussion of what disease stability might look like in the future of COPD care. Rabe and Singh talked about how a patient’s ‘personal best’ might be defined, given the constraints of their unique situation. They went on to talk about the shift in mindset and ways of working that might need to occur to embed disease stability as a part of everyday practice, and what future tools and innovations will be crucial to make this goal a reality.

| Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information for the United Kingdom can be found at www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard or search for MHRA Yellow Card in the Google Play or Apple App Store. Adverse events should also be reported to Sanofi on +44 (0) 800 0902 314. Alternatively, send via email to [email protected] |

MAT-GLB-2505957 – 1.0 – 01/2026