Meeting Summary

Convened during the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Congress 2025, this symposium provided an in-depth discussion of the identification, impact, and management of mucus plugging in the airways, an often underrecognised but clinically important component of asthma disease burden in some patients. Njira Lugogo, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA, reviewed both the methods to identify and quantify mucus plugging and data illustrating the association between mucus plugging and poor asthma outcomes, including increased likelihood of exacerbations, inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and oral corticosteroid use, and rate of lung function decline. Simon Couillard, University of Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada, detailed the Type 2 inflammatory mechanisms involved in mucus plug formation, highlighting the central role of IL-13 and other cytokines and mediators. Mario Castro, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, USA, presented results from studies of biologic therapies showing their efficacy in reducing mucus plugs and improving mucus scores in patients with asthma, correlating with improved airway ventilation and airflow. The symposium concluded with a panel discussion regarding the clinical importance and management of mucus plugging, as well as the role of targeting mucus plugs with biologic treatment, with the goal of achieving disease modification in asthma.

A Sticky Situation: Burden of Mucus Plugging on Patients with Severe Asthma

Njira Lugogo

Mucus plug identification and its impact on patient burden is a relatively new aspect of airway disease clinical management. Lugogo began the presentation with a discussion of a patient case to highlight the clues that could raise clinical suspicion for investigating mucus plugging.

A 35-year-old female non-smoker came to Lugogo’s clinic presenting with a history of persistent cough and dyspnoea upon exertion. The patient noted that she was diagnosed with asthma 8 years prior, with positive skin prick test for multiple allergens, including dog dander, house dust mites, ragweed, and some tree pollens, and reported a history of severe nasal congestion and drainage. She also had a previous diagnosis of nasal polyposis with recurrent anosmia and congestion despite high-dose nasal steroids. She reported a history of eczema, which was then well-controlled. She was currently prescribed ICS with long-acting β agonist 200 µg/5 µg, two puffs, twice per day, and an albuterol nebuliser every 2–3 hours. She had also responded well to oral steroids in the past and had no history of allergen immunotherapy or biologic therapy. Her pre- and post-bronchodilator (BD) forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) were 1.08 L and 1.10 L, respectively; her FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) was 0.43; and her fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) was 54 ppb. Her blood eosinophils were measured at 900 cells/µL and her total IgE was 230 IU. A radiologist’s review of a chest CT scan noted no apparent malignancies/masses, nodules, or interstitial lung disease. A pulmonologist reviewing this CT scan found evidence of mucus plugging in multiple bronchi.

Mucus, a hydrogel comprising water, salt, globular proteins, and high-molecular-weight mucin polymers, supports and protects airway physiological functionality, trapping pathogens and debris and clearing them from the lungs.1 Mucus plugging, however, is a pathological process. Often triggered by inflammatory responses to viral infections, mucus plugs accumulate because of mucin polymer hypersecretion and failure of the body to clear the hyper-concentrated mucus from the small airways via cilial or mechanical (i.e., cough-dependent) actions.1

Mucus plugs are visible on high-resolution CT (HRCT) and are predominantly observed in subsegmental airways as focal or branching opacities, usually in the absence of bronchial dilation.2 Quantification involves counting the bronchopulmonary segments with ≥1 mucus plug(s) on HRCT, assigning a mucus score of 0 (plug absent) or 1 (plug present) to each bronchopulmonary segment, and then adding the segment scores to generate a total mucus score that generally ranges from 0–20.2 Mucus must completely occlude the airway to be considered a plug; partial airway occlusion by mucus is not scored.2

Many patients with asthma have a persistent mucus plug phenotype resulting from a dynamic balance of plug persistence, resolution, and new creation.3,4 Once mucus plugs form, they can be observed occluding the same airway for years. A longitudinal analysis of baseline and Year 3 CT lung scans from participants in the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP)-3 who had mucus plugging at baseline revealed this pattern of persistence in multiple individuals. The mean mucus plug score for the cohort at Year 3 was similar to that at baseline (3.8 versus 3.4, respectively).3 Additional CT scan data from the SARP study tracked the morphology and persistence of mucus plugs, categorising them as ‘stubby’ (≤12 mm), ‘stringy’ (>12 mm), or absent.4 Over 3 years, a portion of plugs present at baseline resolved, some stubby plugs grew larger (i.e., became stringy), and some stringy plugs shrank (i.e., became stubby).4

Mucus plugs are associated with poor lung function and ventilation heterogeneity in individuals with severe asthma. An analysis of SARP data by Dunican et al.2 found that, as mucus scores increase, lung function declines. Of the 146 adult patients with asthma enrolled in SARP that formed the patient cohort for the analysis, 66% met American Thoracic Society (ATS)/ERS criteria for severe asthma. All were non-smokers and had evidence of bronchial hyperresponsiveness or reversible airflow obstruction. High mucus scores, defined as ≥4 bronchial subsegments with ≥1 airway completely occluded with mucus, were significantly associated with low FEV1 in the cohort subset with available multidetector CT lung scans (n=146; p<0.001 versus individuals with no or low mucus scores). They were also significantly associated with air trapping in the cohort subset who had undergone body plethysmography (n=44; p<0.05).2 A separate study investigating ventilation heterogeneity using MRI ventilation defect percentage in 27 patients with severe asthma found a similar pattern, with high mucus scores significantly associated with higher pre- and post-BD ventilation defect percentage compared with low mucus scores (p=0.0008 and p=0.0004, respectively). This study also found a spatial relationship between a focal mucus plug observed on CT imaging and a ventilation defect observed on MRI.5

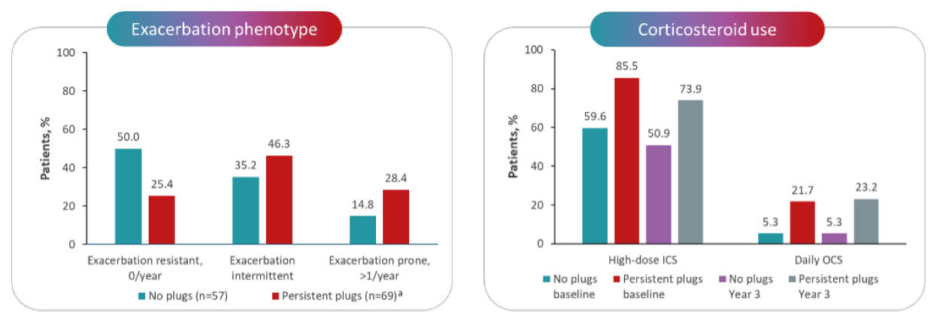

Further analyses of longitudinal SARP data illustrate that patients’ asthma can worsen over time once they develop persistent mucus plugs. Of 69 individuals participating in the SARP study who had mucus plugs at baseline and after 3 years, only 25% had zero exacerbations per year over that time, whereas 28% had ≥1 exacerbation per year (i.e., exacerbation prone) and 46% had an exacerbation-intermittent phenotype. Corresponding proportions for individuals without mucus plugging were 50%, 15%, and 35%, respectively. The persistent mucus plug subgroup also had higher ICS and oral corticosteroid use compared with the group without plugs (Figure 1).3 Pre-BD FEV1 percent predicted (pp) and FEV1/FVC were significantly lower at baseline and at Year 3 in the group with persistent plugs versus the group without and, by Year 3, the median asthma control test score was also significantly lower in individuals with persistent plugs (all p≤0.039).3 This same analysis found that an increase in mucus score over the 3-year period was significantly correlated with declines in the annualised rate of change in FEV1pp, FVCpp, and FEV1/FVC (r=−0.37, r=−0.31, and r=−0.31, respectively; all p<0.001).3 A separate correlation analysis of SARP data found a stronger negative effect of mucus plugs on FEV1pp and forced expiratory flow25-75pp in the proximal airways (generation ≤7) compared with more distal airways (generation ≥10).4 These effects of mucus plugs in the airways have also been confirmed in autopsy studies of fatal asthma cases, where entire large airways are lost due to persistent mucoid occlusion.6

Figure 1: Association of persistent mucus plugs with increased exacerbations and corticosteroid use in the Severe Asthma Research Program.3

*Mucus plugs were persistent between baseline and Year 3.

ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; OCS: oral corticosteroids.

Inflammation to Obstruction: Role of Type 2 Cytokines in Mucus Plugs

Simon Couillard

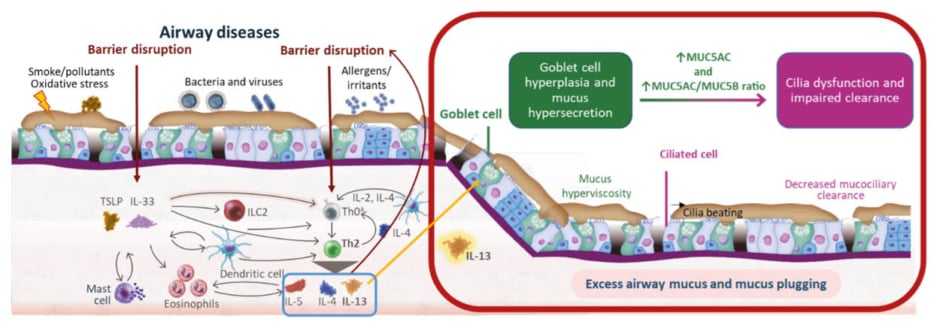

Type 2 inflammation is an important driver of asthma pathophysiology, including the formation of mucus plugs (Figure 2). Disruptions in the protective epithelial lung barrier, which can result from chronic inflammation coupled with exposure to irritants, including smoke, pollutants, oxidative stress, bacteria, viruses, or allergens, trigger a series of processes that result in the generation of the Type 2 cytokines IL-4, IL-13, and IL-5.7-11 These three cytokines, in turn, play distinct, yet sometimes overlapping roles in mediating various aspects of the Type 2 inflammatory response, including Th2 cell differentiation (IL-4); eosinophil differentiation and survival (IL-5); mast cell activation and trafficking to tissues, B cell isotype switching, IgE production, and epithelial barrier dysfunction (IL-4 and IL-13); and eosinophil recruitment and trafficking to tissues (all three IL types).11-14 As a mediator of goblet cell hyperplasia, mucus hypersecretion, and mucociliary dysfunction, IL-13 is a key contributor to mucus plugging. Elevated IL-13 expression results in an increase in mucin 5AC (MUC5AC) and a decrease in MUC5B production, altering their delicate balance in the airway lumen and contributing to mucus hyperviscosity. When combined with decreased mucociliary clearance, these processes ultimately result in excess airway mucus.11,15-17 For example, an in vitro analysis using human bronchial epithelial cultures stimulated by IL-13 showed that MUC5AC expression was dramatically increased in the mucus gel in the extracellular matrix, while the mucus transport rate was significantly impaired compared with unstimulated cultures (p<0.0001).18 Similarly, IL-13 exposure significantly increased MUC5AC expression in a dose-dependent manner in a study using paediatric bronchial epithelial cells from children aged 2–12 years with and without asthma (both p<0.001). Compared with cells from healthy controls, greater increases in MUC5AC mRNA were seen in cells from the children with asthma, which also had higher baseline MUC5AC mRNA levels prior to IL-13 exposure.19

Figure 2: Role of Type 2 inflammation in mucus plug formation.7-17

*T cell differentiation takes place in the lymph nodes and is included in the schematic for the purposes of illustration only.

IL: interleukin; ILC2: Group 2 innate lymphoid cell; MUC5AC: mucin 5AC; MUC5B: mucin 5B; Th0: naive T; Th2: T helper 2; TSLP: thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

In a healthy individual, goblet cells in the lung epithelium generally secrete more MUC5B than MUC5AC, making the mucus gel easily transportable by the cilia. In an individual with asthma, the mucus gel becomes enriched with MUC5AC.20 In the SARP study that was discussed by Lugogo, in which investigators used CT imaging in individuals with asthma to show the association between mucus scores and lung function, having a high mucus score was significantly associated with an increase in the ratio of MUC5AC to MUC5B compared with both having asthma with a mucus score of 0 and healthy controls (both p<0.001).2 Extracellular MUC5AC domains remain tethered to the MUC5AC-producing cells, compromising mucociliary clearance and resulting in the buildup of mucus in the airway.20 Mucus tethering to the epithelial surface may contribute to a state of persistent mucosal folding, leading to decreased airway lumen size and airflow in asthma.21 Additionally, in the presence of this excess airway mucus associated with MUC5AC production and abnormal tethering, eosinophil peroxidase, an enzyme released from airway eosinophils, and Charcot-Leyden crystals, released during eosinophil extracellular trap cell death, have been shown to crosslink mucin proteins and further tether them to the airway epithelium, which can contribute to plug formation.22,23

High mucus scores in individuals with asthma are associated with key mediators of Type 2 inflammation. In the SARP study by Dunican et al.,2 individuals with high mucus scores exhibited expression of IL-13 and IL-5 that was significantly higher than those with no mucus plugs and healthy individuals without asthma (all p<0.05). Additional SARP data showed that elevated sputum eosinophil peroxidase levels were significantly correlated with increases in the average length and volume of mucus plugs (rs=0.31 and rs=0.33, respectively; both p<0.05).4 Similarly, in the study that found a spatial relationship between mucus plugs and ventilation heterogeneity in patients with severe asthma, high mucus scores were associated with significantly elevated FeNO (p=0.03) and elevated levels of IL-4 in sputum (p=0.02).5

Approaching Mucus with Precision: Targeting Disease Modification for Improved Outcomes

Mario Castro

Clinical trial data concerning the impact of treatment on mucus plugging in individuals with severe asthma are limited. However, several recently conducted studies have investigated the efficacy of biologic therapies that target different mediators in the underlying inflammatory processes, including the anti-IL-4 receptor α (anti-IL-4Rα) dupilumab, the anti-IL-5Rα benralizumab, the anti-IgE omalizumab, and the anti-thymic stromal lymphopoietin tezepelumab, for improving mucus-related endpoints and asthma outcomes.24-27 Evidence has accrued from placebo-controlled clinical trials and real-world studies in individuals with asthma, evaluating the efficacy of these biologic therapies for reducing mucus score, mucus volume, and the presence of mucus plugs on HRCT, as well as for improving airway ventilation and volume, lung function, and asthma control.24-30 These treatments have an impact on mucus scores and volume, which correlates with changes in lung function parameters, such as FEV₁ and FVC, and inflammation biomarkers, including FeNO and sputum eosinophils.25,29,31 Together, the findings illustrate how targeting the pathophysiological process of mucus plug formation can impact asthma outcomes in patients with severe disease.

MAT-GLB-2505972 – 1.0 – 12/2025