BACKGROUND AIMS

Insurance is an important social determinant of health that can contribute to health inequities. Many patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) lack health insurance. Between 2017 and 2020, 15.7% of patients with severe TBI in the United States lacked insurance coverage.1 Previous research has shown a relationship between insurance and outcomes following acute trauma care for TBI, such that uninsured patients had shorter hospital lengths of stay, decreased likelihood of discharge to rehabilitation, higher likelihood of mortality, and increased recurrence of TBI compared to those with health insurance.2-5 Few studies have investigated the contribution of insurance to outcomes in patients with TBI who have undergone inpatient rehabilitation.

METHODS

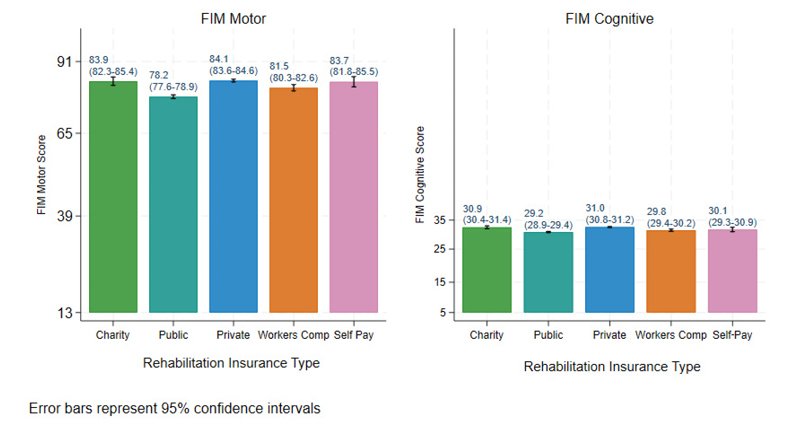

The authors conducted an analysis of the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems (TBIMS) national database to investigate the relationship between insurance payor and functional status 1-year post-injury in individuals with TBI who had received acute level-one trauma care and completed comprehensive inpatient brain injury rehabilitation.6 The TBIMS national database enrolls individuals who meet the following criteria: at least 16 years old at the time of injury; admitted to a TBIMS level-one trauma center within 72 hours of injury; admitted to TBIMS comprehensive inpatient rehabilitation; and a complicated mild, moderate, or severe injury.7 Rehabilitation insurance payor status was classified as charity, private, public (Medicare/Medicaid), worker’s compensation/auto, or self-pay (Figure 1). Functional status was assessed by the 1-year post-injury Functional Independence Measure (FIM)8 motor and cognitive domain scores. The contribution of insurance group to 1-year FIM scores was investigated by linear regression, covarying for age and FIM scores at rehabilitation discharge.

Figure 1: FIM scores at 1 year by rehabilitation insurance type.

FIM motor and cognitive scores at 1 year were analyzed for 5,925 and 7,403 patients, respectively. Self-pay or private pay patients had the highest mean motor scores, while publicly insured patients had the lowest. Privately insured patients had the highest mean cognitive scores, while publicly insured patients had the lowest. After controlling for age and FIM scores at rehabilitation discharge, insurance payor contributed significantly to 1-year FIM motor and cognitive scores. Publicly insured and worker’s compensation and auto insurance patients had lower scores compared to self-pay.

CONCLUSION

The results indicate that publicly insured patients achieved less independent functioning at 1 year, even after controlling for age and functioning at discharge. While the exact mechanism for this disparity cannot be determined from the current data, less access to outpatient therapy and other services to improve functioning should be investigated in future research. The results suggest that publicly insured patients and those with worker’s compensation/auto insurance should be targeted for monitoring to reduce risk factors for poor functional outcomes after inpatient rehabilitation. Future studies should also include other factors that may underlie the relationship of insurance to functional outcomes, including length of stay, geographic characteristics (e.g., urban versus rural areas), and health literacy.