BACKGROUND AND AIMS

Chronic cold urticaria (CCU) is a physical urticaria triggered by cold exposure, leading to wheals or angioedema that typically develop on rewarming and resolve within an hour.1,2 Though usually mild and self-limiting, it can sometimes lead to severe anaphylactic reactions. Diagnosis relies on patient history and cold stimulation tests.2,3

The aim of the present work was to review the clinical features, diagnosis, and response to therapy in a group of patients with CCU followed in an allergy department.

METHODS

Patients diagnosed with CCU between 2009–2024, followed in the authors’ Allergy Department, were included retrospectively. The authors collected clinical and demographic data from clinical process. The statistical analysis of the data was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 28 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). A Chi-squared test was used to measure the correlation between categorical variables. The p values below 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

Eighty-two patients were included. The median age was 37 years (range 4–77; interquartile range [IQR]: 32), and 66% (n=54) of the patients were female. Median symptom onset was 31 years (range 1–72; IQR: 29), and median symptom duration at initial consultation was 5 years (range 0.3–45; IQR: 7). Of the patients, 41% had rhinitis, 15% had asthma, 12% had autoimmune diseases, and 4% had neoplasia. Four patients had other inducible urticarias (three dermatographic and one cholinergic). Triggers included cold air (63%; n=52), aquatic activities (62%; n=51), cold surfaces (45%; n=37), and cold foods/drinks (12%; n=10). All underwent the ice cube test (positive in 30; stimulation time: 1–20 min) or TempTest® (Worthing, UK; positive in 21; threshold temperature: 9–20 ºC). A total of 44 (54%) typical CCU cases and 38 (46%) atypical CCU cases were diagnosed. Secondary CCU causes were found in two patients (essential mixed cryoglobulinaemia and HIV); no familial CCU types were identified.

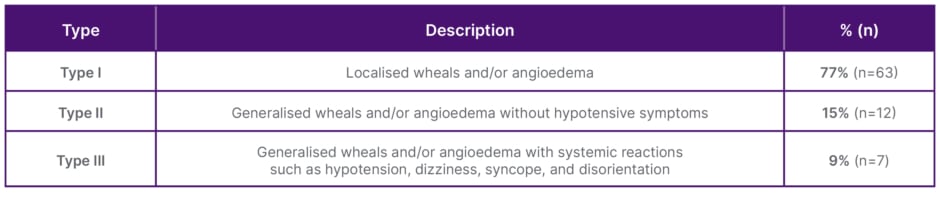

Regarding severity, 77% (n=63) had Type I CCU, 15% (n=12) had Type II, and 9% (n=7) had Type III, with the latter being associated with autoimmune history (p<0.01; Table 1).2,4 Anaphylaxis was noted in 7% (n=6) and angioedema in 18% (n=15). All patients with a history of anaphylaxis reported aquatic activities as a trigger and were equipped with adrenaline auto-injectors. Typical CCU was associated with more severe reactions (p=0.03).

Table 1: Severity grading of chronic cold urticaria.2,4

All patients were counselled on avoidance measures. Treatments included antihistamines (76%; n=62), corticosteroids (12%; n=10), montelukast (10%; n=8), and emergency adrenaline (9%; n=7). During follow-up, 51% (n=40) improved, 30% (n=24) remained unchanged, and 19% (n=15) resolved.

CONCLUSION

Although CCU can be life-threatening, Type I severity was the most common in this sample. Cold air and aquatic activities were the main triggers, highlighting the need for patient education and preventive strategies, especially in colder climates or among those exposed to water. Most patients’ symptoms were controlled with lifestyle changes and antihistamines. The association between Type III severity and autoimmune comorbidities (p<0.01) reinforces the need to screen for underlying conditions in severe cases. Diagnosis was supported by cold stimulation tests (ice cube or TempTest®), though variability in results reflects the heterogeneity of CCU. Avoidance measures and non-sedating antihistamines were sufficient for most patients, which supports current first-line treatment recommendations.2

In conclusion, CCU remains an intriguing and clinically relevant condition, offering insights into physical urticaria mechanisms and underscoring the value of individualised diagnosis and management, particularly in patients with comorbidities or severe presentations.