Abstract

Background: atopic dermatitis (AD) has been related to poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in adults and there is lack of qualitative research that explores how this long-term condition

affects the lives of adults. The purpose of this study was to explore the impact of AD on the HRQoL of adults through semi-structured interviews.

Study design: this was a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews.

Methods: adults with a clinical diagnosis of AD were recruited by advertising on a university campus and through social media sites. All participants completed a screening questionnaire on AD diagnosis, treatment, duration, and severity. Semi-structured interviews were conducted either face-to-face or on the telephone then audio-taped, transcribed verbatim, and analysed using thematic analysis.

Results: the study group (n=19) consisted of 10 White and nine Black and ethnic minority participants, aged 19–52, of whom 18 were female. Three superordinate themes emerged from the analysis: 1) visibility of AD; 2) threats to inner sense of self; and 3) contrasting reactions and support from others. There were qualitative differences in the narratives of those who were diagnosed with AD at an early age compared to a later age, and across ethnic groups.

Conclusions: AD has a great impact on the QoL of adults. Participants in this study discussed issues that have not been reported in quantitative research, particularly around the lack of understanding of the psychological impact of AD and the stigma attached to it. Consideration of these factors may enhance disease management and improve HRQoL. Understanding and recognition of AD as a complex long-term condition involving significant psychosocial impact is crucial. The findings from this study suggest more integrated and accessible psychological support is required for people with AD. Males were under-represented in this study, and further exploration of the impact on AD in males is needed.

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterised by intense pruritus (itch), erythematous lesions, increased water loss through the skin, and xerosis (dry skin). The lifetime prevalence of AD is 10–20% in children and 1–3% in adults worldwide; 85% of affected children develop the disease before the age of 5 years.1,2 Although the condition resolves in many during childhood, AD may persist into or manifest for the first time in adulthood.3 Less than one-half of patients with AD have complete resolution by 7 years of age, and only 60% of them have resolution by adulthood, indicating the chronic nature of AD.4

Importantly, in several studies, subjective experience of AD was a more powerful determinant of quality of life (QoL) than the degree of objective severity, indicated by the area of affected sites.5 However, these measures do not enable us to encapsulate, summarise, and effectively convey the full-life impact of the experience of AD. Existing QoL measures rely on limited questions concerning daily life experience during the day, week, or month preceding the assessment. The vast majority of research assessing QoL in adults is quantitative and much is cross-sectional, thus very little is known about the experience of adults living with AD. The aim of this study was to understand participants’ experiences of living with AD using semi-structured interviews.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This was a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews conducted with adults with AD. The study received ethical approval from the University Research Ethics Committee. Inclusion criteria for this study were adults aged 18 or above with clinically diagnosed AD and consent to take part in the study. The exclusion criteria for the study were participants living outside the UK.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were identified through advertising of the study at a large UK university and via social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. A total of 19 participants were recruited; four were identified through the university, five were identified through word of mouth and snowballing techniques, and 10 were identified through social media.

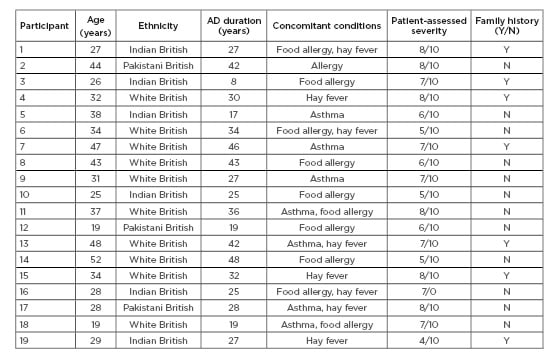

Participants consisted of one male and 18 females, with a mean age of 34 years (age range: 19–52). All participants had concomitant conditions. Ten participants were White British, six were Indian British, and three were Pakistani British. Disease duration ranged from 7 to 50 years. Fifteen participants were being treated by a dermatologist, and seven participants had a family history of AD. Current medication taken by participants included topical corticosteroids, oral immunosuppressants, antihistamines, and over-the-counter creams and ointments. Patient-assessed severity was explored using a non-validated visual analogue scale (Table 1).

Table 1: Participant characteristics.

AD: atopic dermatitis; N: no; Y: yes.

Data Collection

The authors developed an interview schedule led by the second author, drawing upon the findings of a systematic review on the impact of AD on QoL.6 Issues such as sleep, employment, and physical activity, which are commonly found to be disrupted in those with AD, were also explored. Questions were prepared and formatted in a manner that allowed participants to discuss in as much depth about their experiences as possible because the intention was to allow for an exploration of their experience without drawing upon any pre-existing theories. Participants’ experiences of living with AD on a daily basis in general, their relationships with significant others, their experiences with treatment and management of the condition, as well as physical and psychological implications of living with AD were explored. The first author conducted all of the interviews. Questions were framed in an open-ended manner, asking participants to “tell me a bit about your diagnosis of AD,” then slowly moving to more sensitive topics such as “how has AD affected your relationships?” once a rapport between the participant and researcher had been established. The interviews were either conducted face-to-face or over the telephone, then audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

Interview data were analysed thematically, recognising the interaction between the researcher and the data. Thematic analysis has six clearly defined steps: 1) familiarisation with the data; 2) generation of initial codes; 3) searching for themes; 4) reviewing themes; 5) defining and naming themes; 6) and producing the report.7

RESULTS

Three superordinate themes were developed from the analysis of the interviews: 1) experiencing threats to inner sense of self; 2) living with the visibility of AD; and 3) contrasting reactions and support from others.

Experiencing Threats to Inner Sense of Self

The two aspects to this superordinate theme involved the various emotions that participants with AD discussed experiencing as a result of their condition and issues with self-consciousness.

Experiencing intermittent heightened emotional distress emerged as an important theme. Although some participants identified feeling “happy” some of the time, the majority also experienced periods of intense emotional distress that they attributed largely to the unpredictability of their condition and loss of control over their flares. Narratives were punctuated with words that powerfully identified their emotive experience: “worry,” “fear,” “anger,” “pain,” “sadness,” “depression,” “frustration,” “horrible,” and “embarrassment.” Worry or fear (associated with flares); sadness, dysphoria, or depression; and anger and frustration were also connected to AD, and therefore appraised as emanating from the experience of having flares and suffering with the condition for such a long duration. This sense of frustration was closely linked to uncertainty surrounding the allergens and triggers. Participant 5 describes “drowning” in her own misery when she gets a flare-up.

Participant 5: “At that point I was just like, I’m not going to do any work, I’m not going to go to college when I’m like this, I’m just going to sit here and just going to drown in my own misery. [sic]”

Living with a long-term condition such as AD often resulted in an altered view of self. A few participants discussed that their condition had become such a strong part of themselves that they could not imagine life without AD, with Participant 18 describing it as a “constant presence” whereby she could not imagine not being “itchy every day.” Participants reported that AD was responsible for unsightly physical appearance and this often resulted in them conveying various emotions, especially during times when their AD was more severe and prevalent on areas of the body visible to others. Periods of uncontrolled AD were characterised by low mood for some participants. Some used emotive language to describe how they felt about periods of uncontrolled AD. Participants described their mood using words such as “snappy” and “hot-headed” in times of flare-ups. Participant 6 cited her mood as being so low that she stayed confined to her room for days. Many participants also discussed the degree to which their condition threatened their sense of self. The tone of some of the narratives reflected an underlying desire to be “normal,” and a steadfast belief that if their AD were to be cured, it would confer on them a state of normalcy. It reflected their hope for an idealised “normal” self.

Participant 12 described that due to her religion she covered up her skin, but was doubtful of whether she would have the confidence to allow the affected skin to be visible to others because she felt that people within her community would judge as a result of a lack of understanding. Similarly, Participant 17 explained that when she visits Pakistan, she feels more judged and less confident than in the UK, where she believes people are more educated about AD. Many participants also reported feeling bad-tempered, down, depressed, and less tolerant when they had flares. In fact, four participants described being diagnosed with clinical depression as a direct result of their AD. Participant 3 had extensive facial scarring from his AD, which resulted in severe clinical depression, suicidal thoughts, and social withdrawal.

Participant 3: “My skin was so bad on my face that I didn’t want to laugh like it hurt to laugh or smile as well, yeah it did affect my mood a lot when my skin was really bad I was always alone I always wanted to be by myself. [sic]”

Living With the Visibility of Atopic Dermatitis

Most participants were dissatisfied with the appearance of their AD. They felt that their AD looked unsightly and consequently perceived themselves as abnormal. Their scars, pigmentation, and inflammation acted as a constant reminder to the participants and others of their continued suffering. Many felt stigmatised by their condition, particularly when their AD was prevalent on visible areas such as the face, neck, and arms. They believed that others would judge them as having other conditions, such as AD of the scalp being mistaken for hair lice, or their condition being contagious. They appeared to care deeply about what others thought of their AD and strived to keep it hidden so as not to raise any questions or thoughts; Participant 8 explains in the following excerpt about her fear of what others thought of her condition.

Participant 8: “I’d be worried about, you know, whether they were looking at it, I would be looking at them trying to see if they were, their eyes were, you know, sort of drawn to my eczema. I try my very, very best not to let my hands wander and start scratching. So, you know, I try to be aware, you know; a bit more vigilant if I was meeting somebody new. [sic]”

Many participants also felt extremely self-conscious of their condition, to the point that they felt the need to conceal their condition (e.g., wearing long sleeves, covering their legs and feet, wearing corrective foundation on areas with scarring/pigmentation).

Feeling self-conscious in relation to their AD resulted in participants adapting their behaviour in ways to “hide” their AD, such as not liking to see their reflection in the mirror or having their photographs taken. Participants also discussed how their AD made them look “ugly” or “horrible,” with Participant 8 explaining that as a result of having AD on her hands, she felt compelled to hide her hands when shaking hands with others by flipping down the back of her hand. Participant 2 also explains in the following extract how AD has affected her body image, and this is primarily a result of postinflammatory pigmentation, which is a common outcome of severe AD. Similar to Participant 2, other participants also felt vulnerable when exposing their condition to the world.

Participant 2: “I have got pigmentation all over, I have got discoloration, I don’t go out without my foundations. Um, it makes me feel really conscious, especially when you’re talking. I would not be able to talk, sit across, and then speak with somebody eye to eye contact. [sic]”

Contrasting Reactions and Support From Others

When discussing healthcare professionals (HCP), the majority of participants passionately felt that their general practitioners (GP) and primary care doctors did not understand the psychological impact of AD on them, and that there was a general idea amongst participants that GP were not equipped to address and treat mental health issues that arose as a result of AD. Family and friends were a central part of participants’ support network, and many felt that those who knew them for the longest and those who had AD understood the participants’ situations best.

Dismissed by Healthcare Professionals

When exploring perceptions of the care received from GP, most participants reported that GP did not provide adequate information on the condition itself, its aetiology, or prognosis. One participant also felt that healthcare was centred around children and not enough attention or resources were available or dedicated to the adult population.

Several participants expressed having to “push” for further tests or referrals after they presented to their GP with worsening symptoms. Relationships between participants and their doctors were complex. Participants felt that expertise in skin disease varied between GP. Participants reported that GP were sometimes dismissive of the seriousness of their condition. Participants also felt that this attitude reflected either the lack of experience and interest in the area by the GP, or a lack of appreciation of the psychological impact of AD. Participant 18 described never being referred to a mental health professional despite being diagnosed with clinical depression and anxiety and having asked two or three times to be referred to a “proper mental health doctor” and not an unspecialised nurse. She discussed how it would be ideal to have one person who is specialised in her AD and mental health.

For some participants, pejorative or unsympathetic attitudes of their GP contributed to feelings of guilt or decreased self-esteem; however, not all negative experiences with GP were necessarily a ‘failing’ on the doctor’s part. Participants appreciated the difficult nature of skin disease management, and the demands on GP and their responsibilities were also acknowledged by many. The fact the AD is not life-threatening was a key factor in the disease being trivialised by HCP.

A few participants expressed disbelief that a “simple condition” such as AD does not yet have a cure, and how it is not possible with medical “technology being so advanced” that there was no known cure for the condition. A few participants appeared to relate the lack of cure for AD with the limited knowledge of GP and a lack of knowledge and education of the general public regarding AD. With regard to HCP, numerous participants eluded that they provided better care when it came to their condition than their GP, and often took it in their own hands to alleviate flare-ups and educate others of the condition rather than seeking medical help.

Family and Friends

Participants stated that they did not generally engage in speaking about the impact of their condition to friends and family because they do not want to be perceived in a negative light; many had anxieties that it reflected a sign of weakness. Participants of South Asian background were particularly reticent about talking about their condition to others for this reason. For example, Participant 17 discussed that as a result of her family being “conservative,” she did not feel that she could discuss her condition openly with them; similarly, Participant 17 also perceived a lack of education about AD in her family and relatives and therefore chose not to talk about her condition openly. The majority of participants, however, described feeling supported by their parents and siblings, especially in circumstances in which their family members had a history of AD. While many participants reported strangers viewing their condition as contagious, most felt that this was not the case for friends and family who knew of their AD.

Participant 12 discussed how she received negative comments from others about her condition, but this was mainly from the less-developed countries that she had visited to meet family. She described how people in these countries are more “direct” and have “less etiquette” than those in the UK.

DISCUSSION

Summary of Results

This study highlighted that many participants reported a poor body image and confidence. Indeed, the visibility of the condition appeared to affect participants greatly because they felt stigmatised. Participants offered explanations unique to their own life experiences as to why they might have developed AD. The findings also highlighted a possible lack of public awareness surrounding AD, as well as lack of empathy from family and friends. While many participants were keen for others to know more about the condition, many did not engage in speaking about the impact of their condition to friends or family as they did not want to be perceived in a negative light.

WHY DID PARTICIPANTS FEEL MISUNDERSTOOD BY THEIR HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS?

The qualitative methodology of the study elicited complexities in relationships between doctors and patients with AD not apparent in previous studies. Important among these was the appreciation by some participants that time considerations and other pressures may explain the apparent failings of practitioners. The finding that some patients felt that their doctor was a medical technician whose role was to physically treat their skin disease, and that the psychological implications were not within the doctor’s remit, is consistent with the result of a New Zealand study that 37% of general practice patients with psychiatric symptoms had not disclosed them to their GP.8 Cited reasons for not reporting psychiatric symptoms included a perception that a GP is not the most appropriate person to talk to, or that mental health issues should not be discussed, the stigma of mental illness, and factors related to healthcare system, such as time pressures in the consultation. Many participants did not view their HCP as a source of psychological support or management. An unexplored area is how stigmatisation of mental illness might be especially problematic in the setting of skin disease, which is already associated with considerable stigma. This may be accentuated by the perceived trivialisation of skin disease seen in this study and reported elsewhere.9 Patients with AD may be even more reluctant to present psychological symptoms to their GP given these perceptions. This topic deserves further research.

WHY WERE BLACK AND MINORITY ETHNICITIES PARTICIPANTS LESS WILLING TO DISCLOSE THEIR CONDITION TO OTHERS?

In the authors’ study, Black and minority ethnicities (BME) participants were less willing to talk about their condition, with one South-Asian participant acknowledging that her family in Pakistan were less accommodating of her condition than people in the UK. BME participants were also less willing to discuss the impact of AD on their personal relationships; however, this impact appeared to be greater in this subgroup in participants who did choose to discuss the subject. For example, Participant 2 discussed that she was forced to marry when she was 16 years old and, as a result of her husband and his family not being accepting of her AD, she had to resort to divorce. She blamed the failure of her marriage and inability to conceive purely on AD and the lack of understanding of the condition in her community. Skin diseases have special significance and are associated with various beliefs and taboos in different cultures.10 In a multi-cultural society, such as that which exists in the UK, it is important for health professionals to acknowledge that some of their patients from ethnic minority groups may have additional or quite different psychological and social needs from those of the majority of the population. Myths and beliefs about skin diseases can have a profound effect on the patient and affect their ability to cope. Understanding the implications of this is crucial to providing effective care for people with skin disease. Thompson et al.11 reported in a study with South-Asian females born in Britain that vitiligo was related to stigmatisation and this was influenced by, and affected, cultural practices. Indeed, the majority of psychodermatology research has been conducted with White Western populations.11

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This is among the first qualitative studies exploring QoL and mental health in adults with AD. Unlike most studies exploring QoL in adults with skin conditions, the authors’ study had an ethnically diverse and large sample, which allowed for comparisons between subgroups because BME participants comprised almost one-half of the study sample. Issues such as the role of AD in intimate relationships and the implications of visibility in AD were among factors that the study was able to explore, but have not been explored widely in quantitative studies.6 However, the authors’ study lacked male participants, which does not allow for comparison between the sexes, and the findings may not reflect the experiences of males with AD. Additionally, AD diagnosis in the study was self-reported using demographic questionnaires; the questions did, however, explore details surrounding diagnosis, disease duration, and treatment for AD. Additionally, a large sample size of participants would have allowed for a more in-depth analysis and exploration of differences between participant groups.