Meeting Summary

This symposium, which took place during the 2025 European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Congress, aimed to explore the underlying psychology of patient and healthcare professional (HCP) expectations of medical consultations, which can undermine bi-directional communication. Practical guidance was presented regarding how to act on these expectations to improve HCP–patient communication, and objective, real-world evidence of the therapeutic benefits of improved HCP–patient communication were discussed.

Hereditary angioedema (HAE), a rare, genetic condition characterised by acute attacks of swelling, was used throughout the symposium as an example of a chronic condition whereby expectations exist for HCPs and patients regarding medical consultations, and how bi-directional communication can be optimised.

Introduction

The relationship between HCPs and their patients is dynamic, and many studies have focused on understanding what impacts HCP–patient communication and how best to optimise it.1 Effective communication improves patient satisfaction, quality of care, and health outcomes.1

A positive HCP–patient relationship is particularly important for patients with a long-term physical illness that can have a significant impact on wellbeing and quality of life (QoL).1,2 For example, patients with HAE, a long-term condition marked by potentially serious swelling attacks in the extremities, face, trunk, airways, or abdominal area,3,4 have a poorer QoL and higher rates of anxiety/depression than the general population.5-7

This article explores the factors that affect the HCP–patient relationship and how to help ensure quality bi-directional communication, using HAE as an example of long-term physical illness.

Room for Improvement in HCP–Patient Communication

Sorena Kiani-Alikhan, a Consultant Immunologist at the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, UK, presented data from a survey conducted between 2023–2024 showing that there remains room for improvement in HCP–patient communication.8

The real-world survey included 52 physicians and 199 patients with HAE from across France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.8 Physicians completed an online patient record form for each of their patients with HAE, and patients filled in a self-assessment form.8

While physicians and patients were generally in agreement regarding HAE attack locations, with ‘moderate’ to ‘substantial’ agreement for the majority of locations, there was only ‘fair’ agreement regarding disease burden (κ=0.3422) and attack severity (κ=0.4030).8 In terms of overall disease burden, 11.3% of physicians perceived HAE to be less severe than their patients perceived it to be, and 19.0% of physicians perceived HAE to be more severe than their patients perceived it to be.8 In terms of most recent HAE attack severity, 12.5% of physicians perceived the attack as less severe than their patients did, and 26.7% of physicians perceived the attack as more severe than their patients did.8

Kiani-Alikhan concluded that, although disease burden and attack severity are subjective measures, improved communication between HCPs and patients has the potential to enhance management and overall health outcomes in people with HAE.

Why Good HCP–Patient Communication Matters

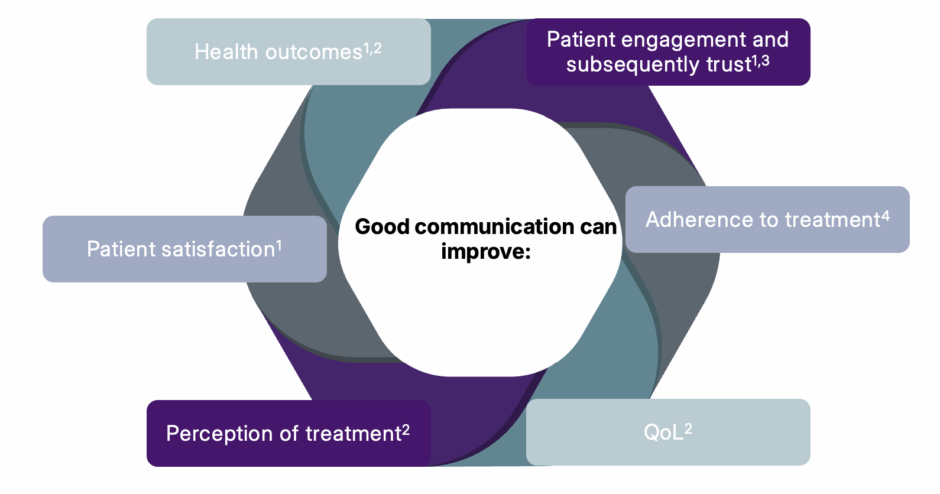

Mari Campbell, a Consultant Clinical Psychologist at the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, UK, explained that good HCP–patient communication can improve health outcomes,1,9 patient engagement, and eventually trust,1,10 patient satisfaction,1 adherence to treatment,11 perception of treatment,9 and quality of life1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Why communication matters.1,9-11

QoL: quality of life.

The Social Graces framework, originally developed by Burnham12 and Roper-Hall,13 is often used to highlight issues of social difference, including power and identity, and may help to make HCPs more aware of biases that may impact therapy.14 The current framework includes 15 areas of social difference: gender, geography, race, religion, age, ability, appearance, class, culture, ethnicity, education, employment, sexuality, sexual orientation, and spirituality.14 Campbell emphasised that HCPs and patients can have different expectations of medical consultations, which can be affected by social differences, and that understanding the value systems and culture of an individual patient supports relationship building.

A Patient’s Expectations of HCP–Patient Communication

HAE UK is a patient organisation that represents 700 patients with HAE in the UK. Angela Metcalfe, CEO of HAE UK, explained that, in her experience, patients can feel intimidated by HCPs, which may prevent them from asking questions about their care. They may also be unsure of some of the medical terminology that HCPs use, and although they may have heard about new treatments for HAE, they may not feel they know enough to ask questions about them. Sometimes patients may feel more comfortable speaking with a nurse than a consultant, and in major clinics where a nurse may see the patient before/after their consultation, strong relationships can be built.

Metcalfe stressed that patients often feel that nobody really understands the psychological burden of living with a rare disease like HAE, and the impact that the disease has on their life. Many patients prefer not to discuss their condition with friends or work colleagues due to embarrassment and fear. Patients may feel that the only people who understand are those who have the same disease, and Metcalfe emphasised the importance of directing patients to patient organisations like HAE UK, so that patients can support each other.

For bi-directional communication to occur in a consultation, Metcalfe explained that it is critical for the HCP to allow the patient to speak, and actively listen to what they have to say, to reinforce a collaborative HCP–patient relationship. It is equally important that the HCP feels comfortable asking their patients general and personal questions about their lives and their experiences of HAE, to build trust and empathy. These types of questions can help the HCP to understand the patient’s background, relationships, support network, dependencies, and personal beliefs.

Metcalfe also pointed out that providing clear, concise, navigable information supported by evidence-based recommendations and choices can ease the burden of disease for patients. While HCPs should share as much information as possible about new treatments or clinical trials, it is important to ensure that the patient understands the HCP’s recommendations for their treatment by asking them for comments and feedback. Patients should also be encouraged to keep clear records of their symptoms so that the HCP can provide optimal care, and the HCP should explain why this is important. Mental health can be severely affected in those living with HAE, and HCPs should also recognise that patients may need additional support and services outside the clinic.

It may be useful to write down notes on a slip of paper for the patient to take away with them at the end of a consultation, perhaps including details of an appropriate patient organisation such as HAE UK. Metcalfe stressed that patients should also be encouraged to bring in a list of questions for their next consultation, to ensure that they remember to ask everything they want to. Patients can be prompted to check their list at the end of the consultation, with a question such as: ‘Is there anything else that you would like to ask me?’

Metcalfe concluded that, by listening, supporting, educating, informing, and understanding, it may be possible to move towards the optimal goal of every patient achieving zero HAE attacks.

An HCP’s Expectations of HCP–Patient Communication

Danny M. Cohn, a Professor of Internal and Vascular Medicine at Amsterdam University Medical Centre, The Netherlands, considers there to be six stages of communication at the clinic, from an HCP’s perspective: preparing, scheduling, gathering information, providing information, shared decision-making, and concluding/managing follow-up.

Preparing

An HCP might prepare for a consultation by reviewing the patient’s notes, checking their prescribed medications, and reading any test results. They might also formulate an initial management proposal and plan for a follow-up appointment.

Cohn noted that one of the challenges of HCP–patient communication that may occur at the preparation stage is that healthcare records can sometimes be dispersed across many different systems, and that patients may have experienced health events that are not necessarily updated in the healthcare system the HCP has access to.

Scheduling

It is important to set expectations of the agenda at the start of a consultation, and Cohn suggested that a simple introductory statement can be helpful, such as: ‘We have about 15 minutes for this consultation. I will invite you to ask any questions that you have prepared, we will discuss how you are doing, and then we will follow up with some management proposals.’

Misalignment between the expectations of the HCP and patient can be a challenge to HCP–patient communication at the scheduling stage. For example, patients may think something is not relevant enough to mention because of time constraints, and may feel they shouldn’t bother the HCP. Equally, an HCP may want to know what’s going on in the patient’s life, but may need to encourage the patient to share these details.

Gathering Information

At this stage, the HCP should invite the patient to share information regarding their expectations of the consultation, their general well-being, and the specific history of their primary condition. They should also be asked if there have been any changes with their treatment, such as adverse effects, and how many days they took, or did not take, their medicine. Finally, the patient should be encouraged to talk about upcoming events that may affect their condition, whether they have a desire to adapt the management of their disease, and to ask any questions they may have prepared.

During this stage of the consultation, it is important for the HCP to strike the right balance in terms of factual or sympathetic language choice. It is also crucial that the HCP asks targeted questions to make sure that they receive the information they need. Cohn used the example of a young female patient with HAE who might be unlikely to share menstrual problems with their HCP unless specifically invited to do so. For HAE, this type of question is important because patients with this condition should avoid taking oestrogens.15 Another example might be asking patients if they are planning any dental or surgical procedures, since these may require the HCP to arrange for additional treatment and to liaise with the surgeon and anaesthetist.

Providing Information

At this stage, the HCP generally provides a preliminary conclusion using a ‘mirroring’ approach. Cohn stressed that the HCP should remain open-minded and express their understanding of what the patient has said, and then ask for confirmation.

The HCP then shares their initial thoughts, such as any additional testing that may be needed, or any treatment adjustments. They can also choose to provide further information at this stage, including recent developments in the field that are pertinent to the patient’s condition. Medical terminology should be avoided, and layman’s terms used wherever possible.

Shared Decision-Making

During this stage of the consultation, the HCP and patient should come to decisions regarding management, follow-up, reporting, and evaluation. Cohn emphasised the importance of ensuring the agreement and cooperation of the patient, and of providing sufficient time in the consultation to achieve this.

Concluding and Managing Follow-Up

In the final stage of the consultation, the HCP should summarise the consultation, provide instructions as needed, and describe the care plan and other management decisions. Cohn encourages the use of a ‘read back’ approach, where the patient is asked to explain or summarise the discussion back to the HCP. This can ensure that the information has been retained and interpreted correctly.

Cohn concluded that it is essential for both the HCP and patient to prepare for a consultation, and that the HCP takes care to listen and ask open-ended questions, as well as targeted questions relevant to the management of the patient’s condition.

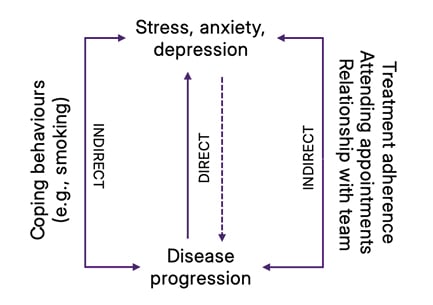

The Relationship Between Mental and Physical Health

The WHO defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease,”16 and a bi-directional relationship exists between physical and mental health17 (Figure 2). Campbell emphasised that the integrated treatment of physical and mental health needs has the potential to improve QoL, relationships with HCPs, and overall prognosis.17 Beyond the well-known direct relationship between physical and mental health, mental health can also directly impact disease progression.17 For example, Campbell explained that, in HAE, anxiety is known to be a trigger for angioedema attacks.18 Indirectly, poor mental health can impact a patient’s ability to manage their condition, leading to poor treatment adherence, difficulties in attending regular appointments, or engaging in less helpful coping strategies such as smoking or drug/alcohol misuse.17 Campbell also emphasised that poor mental health may affect a patient’s relationship with their HCP.

Figure 2: The bi-directional relationship between mental and physical well-being.17

Campbell stressed that having a long-term health condition like HAE does not predetermine that a patient will have mental health difficulties. This means that HCPs have an opportunity to offer evidence-based treatments to help their patients to develop coping strategies that may ultimately improve their physical health.

QoL among patients with HAE has been shown to be poorer than that of the general population,5,6 and the rates of anxiety, depression,5-7 health-related fear, and health-related fatigue are also higher.19 Some of the factors that may lead to anxiety in patients with HAE include delays in diagnosis,7 inadequacy of some treatments,7 uncertainty around attack onset,3 or feelings of life-limitation due to attacks.3 Alongside the increased risk of HAE attacks at times of emotional stress,4 this suggests that a negative feedback loop can develop.

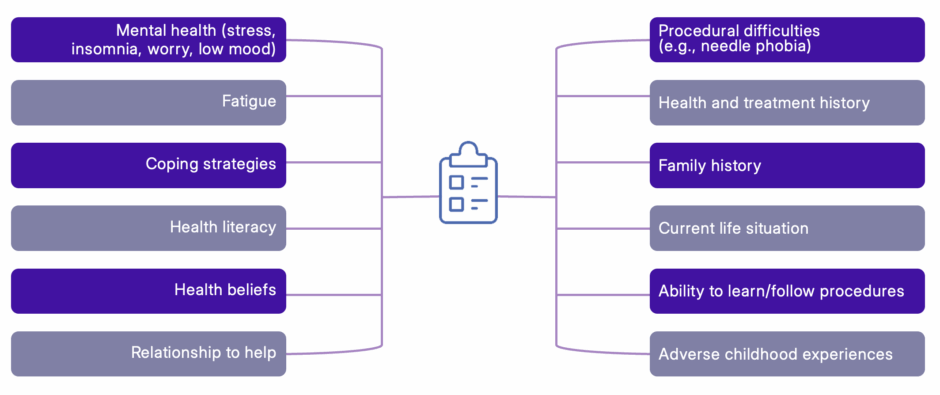

The ‘Therapeutic Alliance’ Between HCPs and Patients

Campbell offered practical guidance on how to establish bi-directional communication between HCPs and patients. She explained that there are many patient factors that impact decision-making in healthcare, including patients’ mental health, which can impact their concentration and memory, making it difficult to engage in conversations and absorb new information (Figure 3). Research suggests that 40–80% of the medical information provided by HCPs is forgotten immediately by patients, and almost half of the information recalled is incorrect.20 Campbell stressed that mental health conditions such as anxiety are likely to further impair information recall.

Figure 3: Patient factors impacting decision-making in healthcare.

Campbell, personal communication.

The ‘relationship to help’, a concept explored by Reder and Fredman,21 is another key factor that affects healthcare decision-making. This concept suggests that patients have a complex collection of beliefs regarding asking for and receiving help, which may influence their relationship with an HCP.21 Such beliefs may include past experiences, or feelings of their own or of other family members.21 Campbell suggested that helping patients to learn about the treatment experiences of other patients may be one approach to addressing issues caused by a patient’s relationship to help. If a patient has had a negative experience prior to the current consultation, they may seek confirmation that the previous HCP managed their condition poorly. In this situation, Campbell recommended listening to the patient and validating their feelings, before redirecting the conversation towards how the current HCP can make sure that they feel safe in the new relationship.

Harmful or life-threatening events or circumstances experienced by a patient can result in trauma, which may leave a lasting impact, affecting a patient’s mental, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual well-being.22 Trauma can also negatively influence the communication between a patient and an HCP.22 Trauma-informed practice is an approach to healthcare interventions that is grounded in an understanding of these issues,22 and Campbell explained that she finds it particularly useful when communicating with patients. The six key principles of trauma-informed practice are to consider safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration, empowerment, and culture.21

Kiani-Alikhan added that adopting a trauma-informed approach may initially feel daunting to an HCP; however, in his experience, taking this empathetic, active listening approach helps consultations to flow more easily. If an HCP feels that they cannot address all the patient’s concerns in the time available, Kiani-Alikhan stressed the importance of remaining transparent and explaining this to the patient, perhaps suggesting the use of email or a follow-up consultation.

In addition to trauma-informed practice, Campbell recommended that, to help establish bi-directional communication between HCPs, consultations should be continuous, dynamic, individually tailored, and patient-centred, and should use supportive language rather than assigning blame.

Key Messages and Takeaways

There is a considerable psychological burden associated with living with a rare disease, and it is critical that HCPs take this into consideration when communicating with patients.2,17

Bi-directional HCP–patient communication can be improved by preparing for a consultation adequately (both HCP and patient), listening, and asking both open-ended and targeted questions (Cohn, personal communication). Ideally, communication should be patient-centred,1 trauma-informed,22 and individually tailored (Campbell, personal communication). Having a short consultation time should not mean that a positive HCP–patient relationship should be sacrificed (Kiani-Alikhan, personal communication).

Good HCP–patient communication can improve treatment adherence, patient satisfaction, health outcomes, and QoL.1,9,11 Patients with HAE are at an increased risk of HAE attacks during times of stress,4 which means that good communication, along with a consideration of each patient’s mental health, may help take us closer to the optimal goal of every patient achieving zero HAE attacks (Metcalfe, personal communication).

MED-00098 July 2025