BACKGROUND AND AIMS

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory condition primarily affecting the genital area, characterised by hypopigmented skin patches, itching, and pain.1 In some cases, LS can also lead to complications like urinary or sexual dysfunction and, more rarely, squamous cell carcinomas arising in areas of chronic inflammation.2,3 Possible risk factors include a family history of LS, metabolic syndrome, and autoimmune disorders. The diagnosis is typically clinical, but histological confirmation may be necessary. Treatment options include emollients, topical corticosteroids, and systemic immunosuppression for severe cases. Traditionally, LS has been considered to be rare, and more common in females, with peak incidence in prepubertal and late adulthood.4 However, recent evidence suggests it may be an underdiagnosed condition, especially in males and children.5,6

This study aims to examine the impact of LS on male paediatric patients by reviewing cases from a tertiary referral centre over the past decade.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

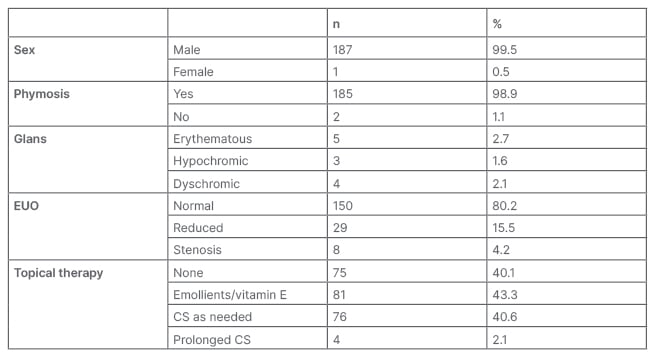

A total of 194 patients aged 18 or under were histologically diagnosed with LS at the authors’ centre, the Modena University Hospital in Italy. Of these, 193 were males. Six patients lacked follow-up data, and were therefore excluded from the study. Mean follow-up duration was 1.9 years. The most frequently affected areas were the foreskin, external urethral orifice, and glans penis, with no perianal or perineal involvement. For clinical characteristics, see Table 1.

Table 1: Patient characteristics.

Results are indicated either as absolute counts (n) and percentages (%).

For parameters other than sex, percentages are calculated on the total of male subjects (n=187). Topical therapy is here not stratified for the type of LS localisation (for details, see main text).

CS: corticosteroid; EUO: external urethral orifice.

RESULTS

Approximately 90% of patients had phimosis as their only symptom, and circumcision led to complete remission in most cases, without the need for adjunctive topical treatments. Active LS in the glans area was observed in 6.4% of cases. Significant external urethral orifice stenosis requiring urological intervention was present in 4.2% of cases, with most not requiring prolonged steroid therapy.

CONCLUSION

The study challenges the traditional view of LS as primarily affecting post-menopausal females, and suggests a higher prevalence in male children.7,8 However, the study acknowledges some limitations, including the lack of systematic histological analysis of foreskin specimens after circumcision. This suggests that LS incidence in the paediatric population may still be underestimated, and routine histological examination of foreskin may be necessary for a more accurate assessment.9

Surgery, such as circumcision and meatal stricture treatment, appears to be an effective first-choice option, eliminating the need for chronic corticosteroid therapy.10 The availability of curative strategies raises questions about whether LS should still be considered a chronic condition, potentially impacting patient care and healthcare systems. However, longer-term follow-up and larger studies are needed to confirm these findings.