Abstract

Nail psoriasis remains a therapeutic challenge that is insufficiently addressed compared to skin and joint involvement. Treatment choices should be personalised and informed by the number of nails affected, the severity of the disease, the impact on daily life, skin or joint involvement, the molecule’s safety profile, patient preferences, adherence to treatment, and accessibility or cost-related issues. Researched treatments include intralesional and topical therapies, laser and light therapies alone or in combination, oral molecules, and biologics. No single intervention fits all patients. First-line treatment consists of topical steroids for nail bed involvement and intralesional steroids for limited disease or nail matrix involvement. When these fail or the disease severity warrants escalation, systemic options, such as biologics, are preferred. When biologics are neither feasible nor desired, alternatives include methotrexate, apremilast, pulsed dye laser, or other therapies.

Key Points

1. Nail psoriasis highlights the need for personalised medicine. Treatment decisions should take into account the number of nails affected, disease severity, its impact on daily life, involvement of the skin or joints, the treatment’s safety profile, patient preferences, likelihood of adherence, and issues related to accessibility or cost.

2. Many treatments have been researched, including topical therapies, light and laser modalities, used alone or in combination, as well as conventional systemic agents and, more recently, biologic and targeted therapies.

3. No single intervention fits all patients. First-line treatment consists of topical steroids in nail bed involvement and intralesional steroids for limited disease or nail matrix involvement.

INTRODUCTION

Nail psoriasis affects up to 40% of individuals with psoriasis and up to 80% of those with psoriatic arthritis.1 It presents a variety of signs involving the nail matrix (pitting, leukonychia, red lunulae, crumbling) and the nail bed (onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, salmon patches, splinter haemorrhages), leading to pain, functional impairment, disfigurement, stigmatisation, and a significant psychosocial burden.2,3 It remains a therapeutic challenge that is insufficiently addressed compared with skin and joint involvement.

Nail psoriasis underscores the necessity for personalised medicine. Treatment choices should be informed by the number of nails affected, the severity of disease (e.g., Nail Psoriasis Severity Index [NAPSI] score), the impact on daily life, skin or joint involvement, and the risk of progression to psoriatic arthritis. Additional factors to consider include the treatment’s safety profile, patient preferences, adherence to treatment, and accessibility or cost-related issues. Furthermore, the unique anatomy of the nail unit and the involvement of both the matrix and the bed create therapeutic challenges, such as limited drug penetration and variable treatment responses, highlighting the importance of individualised and multifaceted approaches.4

Many treatments have been researched, including topical therapies, light and laser modalities, used alone or in combination, as well as conventional systemic agents and, more recently, biologic and targeted therapies.4 This article provides a comprehensive overview of treatment options for nail psoriasis, emphasising their mechanism, efficacy, safety, and role in personalised management strategies.

Despite numerous treatments, standardised guidelines have been lacking.5 However, Rigopoulos et al.2 recently proposed recommendations based on the number of affected nails and the site of psoriatic lesions. Intralesional steroid injections are considered the first-line treatment for limited nail disease (≤3 nails affected; NAPSI: ≤20) with nail matrix involvement. Second-line options include topical corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues, retinoids, keratolytics, and tacrolimus.2,6 For nail bed involvement, first-line treatment consists of topical corticosteroids, either alone or in combination with vitamin D analogues, although evidence supporting the effectiveness of topical therapy remains limited.2

INTRALESIONAL THERAPIES

Triamcinolone acetonide (TA) is the most studied. When injected into the nail bed or matrix, it significantly improves many nail abnormalities, like pitting, hyperkeratosis, ridging, and onycholysis, with the most notable improvement observed in hyperkeratosis.7-9 Boontaveeyuwat et al.9 showed the superiority of intralesional TA over topical clobetasol in nail bed involvement, although superficial injections carry a risk of skin atrophy and telangiectasia.

Methotrexate (MTX) is a more recent option. Mittal and Mahajan11 found that intramatricial MTX had slightly higher efficacy on the NAPSI than intramatricial TA and ciclosporin, though not statistically significant.10 Other studies have shown significant clinical improvement, including a reduction in NAPSI scores, with minimal side effects.11-13 5-fluorouracil has been explored in one study; it was less effective than TA and MTX injections.14

Secukinumab, an IL-17A inhibitor, has been trialled intralesionally for resistant cases. He et al.15 reported a >90% NAPSI reduction in some patients by Week 24 for both nail matrix and nail bed features, along with good tolerability.15

Botulinum toxin Type A (BoNT-A) is the most recently studied agent. A recent RCT revealed that BoNT-A was as effective as TA at Week 16, and continued to show improvement beyond Week 16, particularly in nail bed psoriasis. Smaller case studies corroborate its efficacy and tolerability.16

TOPICAL THERAPIES

Topical corticosteroids, particularly clobetasol, remain the first-line treatment for nail bed involvement. According to Sánchez Regaña et al.,17 onycholysis, pitting, and salmon patches are the clinical signs that showed the best improvement.

Vitamin D analogues, including calcipotriol, calcitriol, and tacalcitol, have shown varying success. Kokelj et al.18 and Zakeri et al.19 demonstrated efficacy in reducing hyperkeratosis and onycholysis; however, there was no statistical difference when compared with betamethasone dipropionate ointment alone or combined with salicylic acid.20,21 Combination therapies of vitamin D analogues with corticosteroids enhance effectiveness. Rigopoulos et al.22 and Sánchez Regaña et al.17 showed synergistic effects on both matrix and bed lesions over 6–12 months. On the other hand, the RCT conducted by Tzung et al.23 reported no difference between this combination and the use of calcipotriol alone.

Tazarotene, a topical retinoid, presents no significant difference in efficacy compared with topical clobetasol in terms of pitting, onycholysis, hyperkeratosis, and salmon patches; however, it yields a more sustained improvement in subungual hyperkeratosis at Week 12.24 In the study by Fischer-Levancini et al.,25 the NAPSI improved by up to 88% at 6 months, but some cases of irritation were reported. Tretinoin 0.025% cream showed a promising result in a case report; however, further investigation is needed.6

The phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor roflumilast 0.3% cream was tried in two patients, showing complete lesion clearance and good tolerability after daily use for 4–5 months.26,27 Johnston and Poelman27 reported a case of nail psoriasis treated with daily roflumilast 0.3% cream. After 5 months, the patient had complete resolution of pain, erythema, and periungual scaling, along with full nail regrowth without onychodystrophy. The treatment was highly effective with no adverse effects.27 Jasso-Olivares et al.26 conducted a retrospective study on seven treatment-resistant patients using daily roflumilast 0.3% cream for 16 weeks. The mean NAPSI score significantly dropped from 19 to 6.8. Most patients achieved near-complete clearance, improved quality of life, and reported no adverse effects.26 Apremilast lacquer also showed promise but still lacks robust clinical trial data.28

Topical calcineurin inhibitor, tacrolimus 0.1%, applied without occlusion, proved effective for both nail matrix and nail bed signs in an RCT reporting >50% NAPSI reduction.29

Ciclosporin was first topically investigated in a case report by Tosti et al.30 using a 10% concentration, with 0.2 mL applied once daily. A marked improvement was observed after 2 months, with near-complete lesion clearance after 3 months.30 An RCT conducted in 2003 utilised a 70% ciclosporin emulsion, resulting in a 77% improvement in some patients.31 It was later mentioned that the instability of the emulsion might contribute to treatment failure.32

5-fluorouracil topical formulation has mixed evidence. While early studies showed some improvement, especially when combined with urea for better penetration, others failed to demonstrate superiority over placebo.33,34 The risk of onycholysis or irritation limits its use.

‘Natural products’ such as indigo naturalis were mostly investigated by Lin et al.35 in RCTs and case reports. The mean reduction in the NAPSI score was 51.2% after a 3-month treatment consisting of a twice-daily application over 24 weeks, thus outperforming calcipotriol.35 All articles discussing intralesional and topical treatment in nail psoriasis are compiled in Supplementary Table 1.

LASER AND LIGHT THERAPIES

Lasers have been explored as potential treatments for nail psoriasis, showing varying degrees of efficacy.

The pulsed dye laser (PDL) is the most studied. It afforded a significant reduction in total, matrix, and bed NAPSI scores, though fluence higher than 8 J/cm2 did not yield a superior outcome.36 Nevertheless, results remain heterogeneous due to variations in pulse durations, study design, and baseline NAPSI scores. Comparative studies have demonstrated that PDL is as effective and safe as intralesional corticosteroids, intense pulsed light (IPL), neodymium:yttrium-aluminium-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser, and photodynamic therapy (PDT).37-40 Only one study found superior outcomes with topical calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate compared with PDL alone.41 PDL caused less pain compared with IPL and Nd:YAG laser. Reported side-effects were generally mild and transient, including pain, purpura, and petechiae.36,39,40 Given its tolerability, PDL may be considered a reliable treatment for nail psoriasis, but larger RCTs must confirm its long-term efficacy before establishing standardised treatment protocols.

The long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser has shown conflicting results.42 Some studies reported an improvement in matrix and nail bed parameters, like subungual hyperkeratosis and onycholysis, and other studies have shown no change in total or nail bed NAPSI scores, limiting benefits to matrix involvement.43,44

The 10,600-nm fractional CO2 laser (FCL) is a promising treatment for nail psoriasis, particularly in laser-assisted drug delivery. It improves nail bed remodelling and enhances the penetration of topical agents. Multiple studies have shown that FCL, either alone or in combination with topical treatments such as calcipotriol/betamethasone or MTX, significantly reduces total NAPSI scores and improves symptoms like pitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis. Combination therapies often showed better clinical outcomes than monotherapies, but most differences were not statistically significant.45,46 A recent case report even described resolution of refractory single-nail psoriasis after one session of FCL-assisted MTX delivery.47 Despite these encouraging results, there is a lack of rigorous trials comparing FCL to established treatments such as intralesional MTX or corticosteroids in resistant cases.

PDT and IPL have surfaced as risk-free and encouraging approaches for treating nail psoriasis. Aminolevulinic acid, activated by red light, demonstrated superior results at the 24-week follow-up compared with clobetasol 0.05% ointment.48 Variants of PDT have also been explored: a combination of PDL with methyl-aminolevulinic acid showed no additional benefit compared with PDL alone,37 methylene blue-assisted PDT was more effective in nail bed lesions than IPL.49

Non-ablative bipolar radiofrequency, generating dermal heat with anti-inflammatory effects, and microneedling with enhanced topical drug delivery via the microchannels, have emerged as potential treatments, though each has so far been explored in a single study.50,51

Excimer laser showed limited efficacy compared with PDL.52

All articles discussing laser and light treatment in nail psoriasis are compiled in Supplementary Table 2.

SYSTEMIC TREATMENTS

Several systemic treatments are available and effective for managing nail psoriasis.

MTX inhibits dihydrofolate reductase, thereby reducing lymphocyte proliferation.53 It is, however, associated with many side effects that sometimes limit its use. It is contraindicated in pregnant women, individuals with severe liver disease or renal impairment, and patients with HIV. MTX has moderate efficacy in nail psoriasis. In the study by Warren et al.,54 which compared MTX (17.5 mg weekly, increased to 22.5 mg for non-responders) with placebo, total nail clearance was achieved by 5% of patients in the MTX group versus 0% in the placebo group at Week 16, and 14% achieved clearance by Week 52. Another study by Gümüşel et al.55 compared MTX with cyclosporine in a 24-week single-blind randomized trial, showing a NAPSI reduction of 43% in the MTX group versus 37.2% in the ciclosporin group. Several side effects, such as myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity, have been reported. Pulmonary fibrosis should also be kept in the prescriber’s sight, especially if the patient uses other medications known to cause such a side effect, like nitrofurantoin.

Ciclosporin is a calcineurin inhibitor that blocks T cell activation and IL-2. It is effective in treating nail psoriasis and is given for short-term use.2 Ciclosporin is not contraindicated during pregnancy, although it has been associated with low birth weight. In an open-label study of 18 patients, 44% had ≥50% NAPSI improvement after 12 months.56 In patients with psoriatic arthritis and nail psoriasis, ciclosporin achieved a 44% improvement in NAPSI score, compared with 56% for adalimumab and 100% for combination treatment.56 One study showed a 79% improvement in nail features when ciclosporin was combined with calcipotriene, while 47.6% improved with ciclosporin alone.57 Despite its effectiveness, ciclosporin’s use is limited by its high side effect profile and potential kidney damage in the medium and long terms.58

Acitretin is a retinoic acid with anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects. It is contraindicated in individuals with severe liver disease and pregnancy, requiring 3 years of contraception after discontinuation. It has moderate efficacy in nail psoriasis. In a study by Tosti et al.,59 low-dose acitretin (0.2–0.3 mg/kg/day) given for 6 months led to a 41% NAPSI improvement and complete or near-complete nail clearance in 25% of patients.59 Another study involving 41 patients treated with acitretin (0.6–0.8 mg/kg) for 6 months showed improvements in nail matrix and bed thickness, although with no effect on enthesopathy and vascular inflammation.60 A case report described a patient with severe, treatment-resistant nail psoriasis who improved significantly after taking 25 mg/day of acitretin for 2 months, with continued improvement over 6 months.61

Alitretinoin, or 9-cis-retinoic acid, did not show a significant difference at Weeks 12 and 24, when compared with placebo in a Phase II randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study.62

Apremilast is an oral phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor that increases intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate and modulates immune responses by blocking pro-inflammatory cytokines and promoting anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10.63 It does not require baseline laboratory tests or monitoring during treatment. It should be avoided in pregnancy, in children <6 years, and in patients treated with strong cytochrome P450 inducers. It is a convenient, non-immunosuppressive oral treatment often preferred by patients seeking non-injectable options. The ESTEEM 1 and 2 trials included 1,255 patients with nail psoriasis, comparing apremilast 30 mg twice daily with placebo. By Week 16, apremilast reduced nail psoriasis severity scores by about 22.5–29.0%, while the placebo showed little to no improvement. Around one-third to nearly half of patients achieved at least 50% improvement by then. Benefits continued through Week 32 and Week 52.64,65 The LIBERATE trial showed a maintained response up to 2 years.66

Tofacitinib is a JAK-1/2/3 and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor. The higher dose of tofacitinib (10 mg twice daily) showed better improvement in nail psoriasis than the lower dose (5 mg twice daily), observed as early as Week 12, with a sustained response through Week 52.67,68 Upadacitinib is a selective JAK1 inhibitor with a promising effect on nail psoriasis.69 All JAK inhibitors carry black box warnings for serious adverse events, including infections, malignancies, thrombosis, and fetal toxicities, requiring careful risk–benefit assessment. Deucravacitinib is a new selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor with a promising effect on nail psoriasis and a favourable safety profile.70 Real-world studies demonstrated significant improvement and sustained clearance rates up to 52 weeks.70,71 A case report highlighted its potential in refractory nail psoriasis but also noted some adverse effects that required discontinuation.72 While generally well tolerated, some adverse events, including oral ulcers and pruritus, have been reported, highlighting the need for continued safety monitoring. Further large-scale studies are needed to confirm its safety and efficacy.

All articles discussing oral treatments in nail psoriasis are compiled in Supplementary Table 3.

BIOLOGICS

Biologics are an option for cases involving multiple nails, treatment-resistant disease, extensive skin or joint involvement, specific patient preferences, or a significant impact on quality of life.73,74 Several agents are effective, including the following: TNF-α inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, certolizumab, golimumab), IL-12/23 inhibitor (ustekinumab), IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab, risankizumab, tildrakizumab), and IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, bimekizumab, netakimab). Improvement tends to be slower than in cutaneous psoriasis, closely linked to the skin and joint response, and is typically faster in fingernails than in toenails.75

TNF-α inhibitors were the first biologic agents approved for the treatment of nail psoriasis.76 Etanercept, a TNF-α inhibitor, reduced the NAPSI score by 50–90%, with a significant improvement in quality of life. Notably, etanercept combined with MTX resulted in greater NAPSI score reductions than MTX alone.73 On the other hand, combining adalimumab and ciclosporin can achieve a 100% NAPSI score improvement.77 A prospective study demonstrated that infliximab was more effective than adalimumab and etanercept by Week 14.78 Simultaneously, a network meta-analysis showed the superiority of infliximab among TNF-α inhibitors in improving nail psoriasis both in the short and long term, likely due to higher blood concentrations achieved through its intravenous administration.79,80 Among IL-17 inhibitors, a network meta-analysis found that ixekizumab was superior to brodalumab and bimekizumab. Additionally, the rates of complete nail cure followed the order of efficacy: ixekizumab, adalimumab, brodalumab, bimekizumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab.81 Multiple trials have shown that ixekizumab yields higher response rates in nail psoriasis compared to etanercept, guselkumab, ustekinumab, and adalimumab.82-85 Similarly, a systematic review emphasised the superiority of ixekizumab over other biologics.86 Huang et al.79 found that infliximab ranked first among biologics for short-term nail psoriasis treatment (10–16 weeks), while ixekizumab outperformed other agents in the long term (24–26 weeks). A network meta-analysis by Khan et al.87 in 2024 reported the greatest mean improvements in NAPSI scores at 24 weeks with brodalumab and etanercept, while complete nail psoriasis resolution was achieved with ixekizumab and adalimumab. These findings suggest that ixekizumab may be the most effective biologic for achieving complete nail psoriasis resolution over the long term. Nail psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are closely related both anatomically and clinically, a connection further supported by the superior efficacy of ixekizumab and infliximab, leading agents among IL-17 and TNF-α inhibitors, respectively. The TRANSFIGURE trial studied secukinumab, an IL-17A inhibitor, specifically in patients with nail psoriasis, and found sustained long-term efficacy.76 Both secukinumab and brodalumab were considered superior to ustekinumab.88

Biologic treatments carry many risks; therefore, the choice should be tailored to the patient’s comorbidities and medical history. Common adverse events range from mild signs, such as injection site reactions and upper respiratory tract infections, to serious complications like severe infections or allergic reactions. Special consideration should be given to the relative safety of TNF-α inhibitors during pregnancy, while caution is advised with IL-17 inhibitors because of their potential to exacerbate inflammatory bowel disease. In summary, biologics represent an effective treatment option with an acceptable safety profile and a remarkable improvement in quality of life. All articles discussing biologic treatments in nail psoriasis are compiled in Supplementary Table 4.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVE

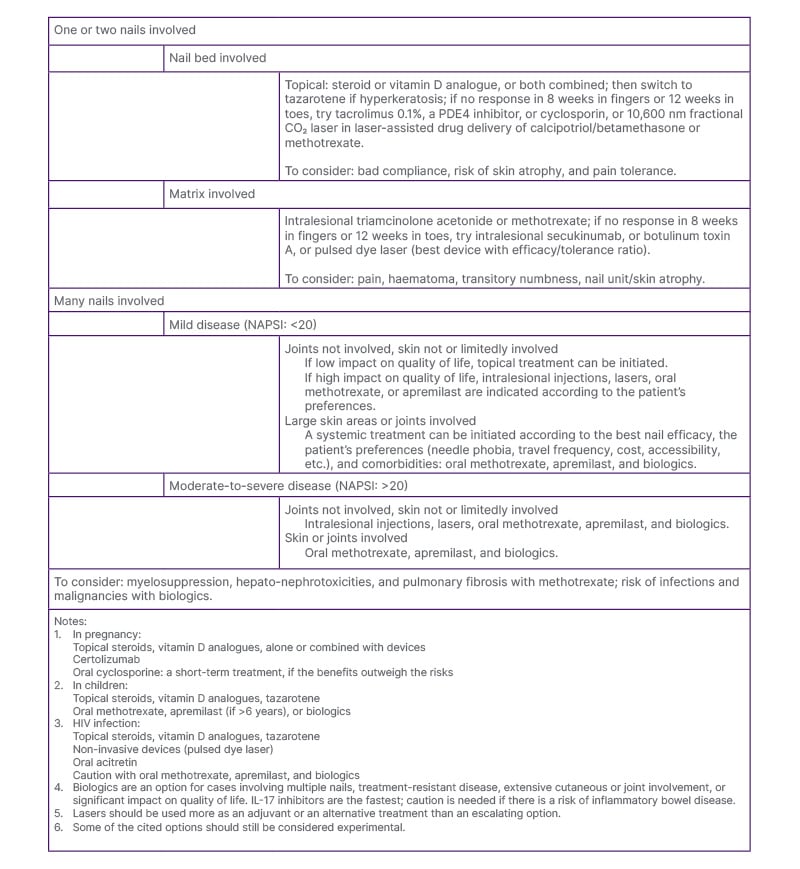

As the authors’ understanding of the condition evolves, it becomes increasingly clear that no single intervention is suitable for all patients. A tailored treatment approach, guided by disease severity, number and location of affected nails, joint or skin involvement, impact on quality of life, and patient-specific factors such as comorbidities, preferences, and treatment access, is crucial (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Suggestions for nail psoriasis treatment in daily practice.

NAPSI: nail psoriasis severity index; PDE4: phosphodiesterase-4.

First-line treatment usually involves topical agents such as calcipotriol, high-potency corticosteroids, or tacrolimus. If these fail or if the disease severity requires escalation, systemic options like biologics (TNF-α inhibitors, ustekinumab, secukinumab, or ixekizumab) are preferred. When biologics are neither feasible nor desired, alternatives include MTX, apremilast, intralesional corticosteroid injections, PDL, or other therapies. In this context, personalised medicine is not just ideal; it is crucial for optimising clinical outcomes, reducing adverse effects, and enhancing both functional and psychosocial well-being.