Abstract

Objectives: To understand the experiences of patients with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis (AD) and their caregivers, the impact on everyday life, and identify unmet needs throughout the care journey.

Methods: This was a qualitative study including 120 patients aged ≥3 months–17 years with mild-to-moderate AD and their caregivers, conducted across China, Saudi Arabia, Spain, and Portugal. Participants were recruited from both public and private healthcare settings. Data were collected through 75-minute remote, semi-structured interviews and three 5-minute video diaries. Data were coded and analysed using an inductive and deductive thematic approach.

Results: AD significantly impacted patients and caregivers across three key areas: lifestyle adjustments, emotional well-being, and future concerns. Reported challenges included activity limitations, food restrictions, and disruptions to caregiver work–life balance. Emotional impacts such as anxiety, bullying, self-image concerns, and peer avoidance were common. Caregivers also expressed concerns about disease chronicity and academic success. Unmet needs included: limited knowledge and information, restricted access to specialists and government aid, insufficient support for disease management, inconvenient emollients, lack of support for positive self-image, inadequate life-stage guidance, and lack of recognition of gender norms.

Limitations: The retrospective design may have introduced selection and misclassification biases. In addition, asking participants to recall their full care journey adds a relevant risk of recall bias, particularly for those with a longer disease history. This reliance on long-term memory may have affected the accuracy of reports about early symptoms, decisions, or emotions. Virtual interviews may also have increased social desirability bias and limited non-verbal observations.

Conclusions: This study reveals that AD affects not only daily life but also emotional well-being and future outlook. Addressing the unmet needs requires holistic strategies combining education, improved communication, and digital tools across life stages.

INTRODUCTION

AD is a chronic, relapsing inflammatory skin disorder characterised by eczematous lesions and persistent pruritus, beginning in early childhood.1 It is one of the most common skin diseases globally, with a prevalence estimated to be up to 20% in children.2 The AD prevalence has increased over the last 40 years, a trend that has been associated with an urban environment, higher socioeconomic status, higher level of family education, family history of AD, female sex (≥6 years), and smaller family size.3

Beyond its clinical manifestations, AD greatly impacts the quality of life, affecting not only patients but also their caregivers, with management often requiring careful attention to addressing lifestyle factors like diet, clothing, and environmental triggers.2,4-8 Thus, a holistic approach involving a regular skincare routine, trigger avoidance, and lifestyle adjustments is key for effective AD management. These demands can be physically, emotionally, and socially burdensome, especially in paediatric cases where caregivers often take on the primary responsibility for disease management. Although existing research has examined the effects of AD on patients’ lives, the emotional and practical toll on caregivers is less well understood.

Several studies in mild-to-moderate AD emphasise patients’ low adherence to topical treatments and highlight the importance of patient and caregiver education to improve this aspect, particularly by informing them about the mechanisms of action and importance of these medications, and by scheduling a follow-up visit shortly after the first consultation to better discuss long-term AD management.9,10 Yet these interventions often fail to address broader concerns related to psychosocial well-being, daily life limitations, and the long-term nature of the disease. Age-related differences in treatment expectations and needs have been addressed in some studies.11,12 The impact of AD extends into areas such as social interactions, participation in school or recreational activities, and self-esteem, especially in adolescents and young adults.13,14 Therefore, the aim of this study was to gain an understanding of the patient and carer experiences of living with AD, the impact on their everyday life, and to identify unmet needs throughout the care journey.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This was a qualitative study including patients with mild-to-moderate AD and their caregivers. They were recruited via secondary care-based services (dermatology, allergy, paediatric departments) from both public and private healthcare settings located in China, Saudi Arabia, Spain, and Portugal from April–June 2023. These countries were purposefully selected as study sites to enable meaningful cross-cultural comparison, especially of the impact of AD on patients and their caregivers. Country selection was informed by both practical and scientific considerations. From an operational perspective, qualitative interviews were conducted by trained ethnographers who were native speakers and nationals of the countries in which the research took place, ensuring linguistic accuracy, cultural sensitivity, and contextual depth in data collection. The availability of trained, native-speaking ethnographers in these countries supported rigorous and culturally grounded data collection. From a conceptual standpoint, these countries collectively represent distinct and complementary cultural regions, including Western Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East. This design allowed the study to capture perspectives from regions with differing sociocultural norms, family structures, and healthcare systems, while also addressing a notable gap in the literature regarding patient and caregiver experiences of AD in Middle Eastern settings, which remain comparatively underrepresented in qualitative research.

The inclusion criteria were patients aged ≥3 months and ≤17 years (with their carers) who agreed to participate, provided informed consent, had a documented diagnosis of mild-to-moderate AD for 12 months prior to the study, and exhibited signs or symptoms suggestive of AD. Exclusion criteria included patients with severe AD, patients <3 months old, and those who had not used any form of treatment for more than 3 months.

Participants were contacted and interviewed by an anthropologist, and the subsequent research was conducted by a team of ethnographers specialising in qualitative studies. All participants gave their informed consent before they were included in the study, with legal guardians responsible for providing consent on behalf of the children. The study was conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices. As this was a non-interventional study that did not involve clinical procedures, it did not undergo review by an institutional review board or ethics committee.

Data Collection

Data from participants were obtained through a 75-minute, remote, semi-structured interview moderated by an ethnographer. These qualitative interviews were based on an interview guide consisting of open-ended questions to elucidate the lived experiences of individuals dealing with mild-to-moderate AD, allowing participants to share insights about their condition. Patients aged ≥13 years were asked to join their caregivers or complete the interview alone. The interviews were followed by three 5-minute video diaries to capture spaces, objects, and daily situations linked to their emotions and experiences with AD. These video diaries were created by caregivers, with input from ≥13-year-old patients if they wished to participate. This helped to understand how the disease affects their everyday life and how they cope with it.

The outcomes of interest included description of patient characteristics, patients’ medical experience, and emotional perception (values, attitude, feelings) during the AD journey, including the role of the carer, main barriers experienced by patients in the healthcare pathway, and general unmet patient needs (cognitive, emotional, and functional) associated with AD.

Data Analysis

Data from the interviews were coded independently by three researchers. Each researcher initially analysed the interviews they had conducted, after which codes and analysis were reviewed and discussed with the rest of the team. The coding methodology involved the application of categories or themes, providing a structured analytical framework grounded in thematic analysis that enabled both a flexible and systematic examination.15 The process of coding was conducted using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) following an inductive and deductive approach. After an initial reading of all transcripts, the research team defined the preliminary analytical categories based on the study objectives (deductive) as well as enabling the emergence of additional themes from the data (inductive). These categories were organised into an Excel table, and interview excerpts were distributed among the thematic columns according to their content. In a subsequent analytical step, a second Excel file was created to capture common patterns among data, which were organised to generate the key insights of the study. To ensure analytical consistency, the three researchers conducted this process independently and compared their coding outputs regularly. Any discrepancies were discussed in joint analysis sessions, during which the raw data were revisited until consensus was reached. All themes included in this manuscript had reached empirical saturation, defined as the point at which no new data emerged from interviews.16 In line with the evidence showing that multisite and cross-cultural studies require between 20–40 interviews per site to reach saturation of metathemes, saturation in the authors’ study began to be observed after approximately 20–25 interviews per country and was confirmed when subsequent interviews did not generate additional concepts.17

Participants were recruited using a purposive sampling strategy in order to capture a wide range of patient experiences across different contexts within each country. The total sample of 120 patients with 30 patients from each country was considered appropriate to ensure qualitative rigour, while providing sufficient representative data in each country. Purposive sampling was implemented with the objective of ensuring variation in treatment status (70% of the patients expected to be on treatment and 30% off treatment), and area of residence (70% from urban settings and 30% from rural areas). Treatment was defined as the use of at least one topical anti-inflammatory medication and one emollient. Categorical variables were described as frequencies and percentages.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

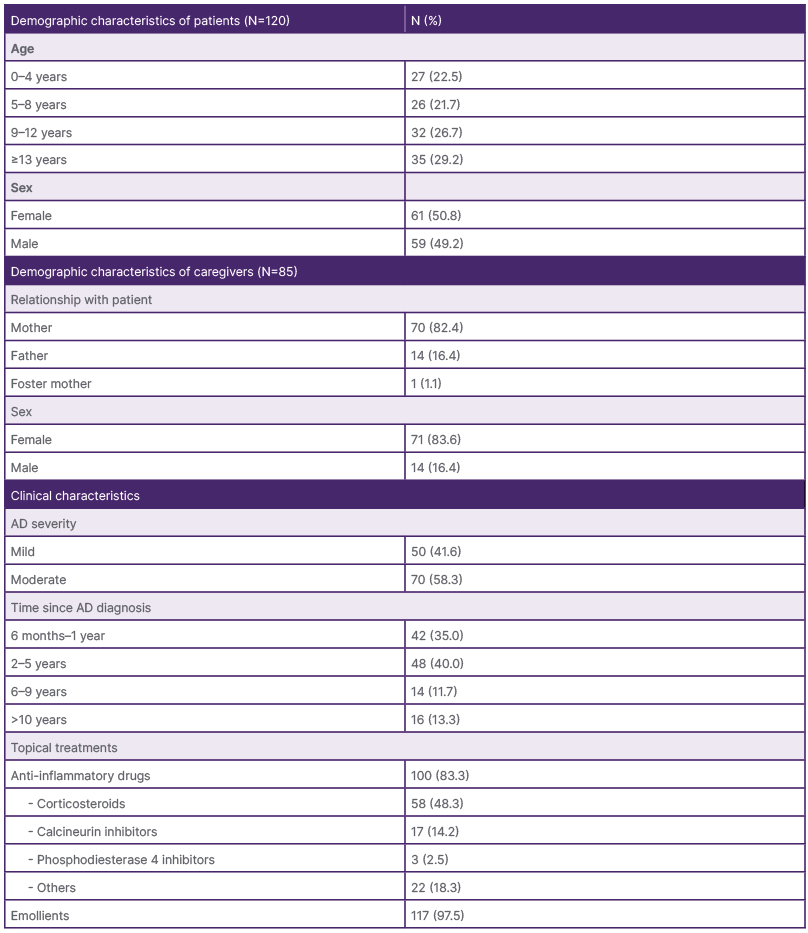

A total of 120 patients and caregivers were included in the study, equally distributed across four countries (30 per country). Of these, 61 (50.8%) were females and 59 (49.2%) were males. The main demographic characteristics of patients and caregivers are summarised in Table 1. More than 50% of the patients were aged ≥9 years and had moderate AD. Most of them had been diagnosed with AD between 2–5 years before being included in the study. Additionally, the majority of patients were currently under treatment for their condition with either topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of study participants.

AD: atopic dermatitis.

Care Journey

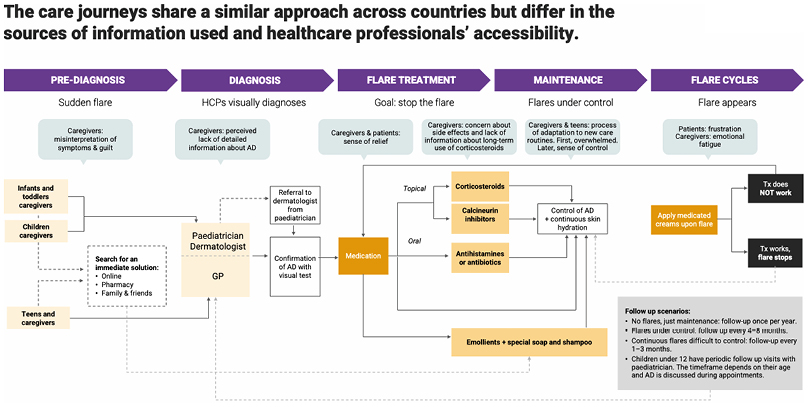

Participants’ accounts described different temporal phases within the AD care journey. When these accounts were compared across participants, a recurring temporal structure emerged from the data, consisting of six phases: pre-diagnosis, diagnosis, flare treatment, maintenance, and flare cycles (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1: Atopic dermatitis care journey.

Representation of patients’ and caregivers’ experiences across phases of AD management, including clinical follow-up and treatment-related decisions. The phases were inductively identified through thematic analysis of participant interviews and reflect distinct actions, perceptions, and emotional responses experienced by both patients and caregivers.

AD: atopic dermatitis; GP: general practitioner; HCP: healthcare provider; Tx: treatment.

Pre-diagnosis

The skin suddenly flared, showing itchiness, dryness, redness, and skin bumps. Caregivers often misinterpreted the symptoms with allergy or heat rash and had a sense of guilt and doubted whether they have been negligent. Caregivers suddenly faced the urgency of relieving their children’s discomfort and searched for an immediate solution online, consulting retail pharmacists, family members, and friends, hoping for some guidance. In China and Saudi Arabia, caregivers commonly consulted online sources experimenting with dietary restrictions (e.g., avoiding dairy, eggs, seafood) or traditional home remedies, including herbal baths or olive oil. In contrast, caregivers in Spain and Portugal were more likely to consult retail pharmacists for over-the-counter solutions.

Diagnosis

Caregivers visited their paediatrician or a dermatologist who visually diagnosed AD and recommended specific skincare routines. Caregivers felt at ease with a mild-moderate diagnosis, yet many caregivers reported that the communication with healthcare professionals (HCP) was limited and they often did not receive detailed information about AD, its nature, characteristics, and what to expect. Furthermore, they reported lacking reassurance on proper management of AD.

In China and Saudi Arabia, caregivers directly visited dermatologists as the online appointment system allowed agile direct access. In contrast, in Portugal and Spain, the initial point of contact was almost always the paediatrician, following healthcare system protocols. Paediatricians then referred the patient to a dermatologist, in case of severe flares.

Flare treatment

HCPs usually prescribe topical corticosteroids during flares and recommend emollients for daily management. An effective flare treatment provided caregivers and patients with a sense of relief. Dermatologists trusted and prescribed calcineurin inhibitors with confidence, especially when corticosteroids had not achieved expected results. However, caregivers often hesitated to use corticosteroids due to concerns about potential side effects, aiming to minimise harm by limiting their duration of use. These concerns were further reinforced by their perception of not receiving clear and assertive information regarding the potential long-term effects of corticosteroid use.

In China, caregivers expressed particular concern about side effects that may affect physical appearance, especially in girls, such as skin darkening and unwanted hair growth. In Portugal and Spain, the primary concerns revolved around increased skin sensitivity and thinning of the skin.

Maintenance

During the maintenance phase, caregivers and older patients learnt how to self-manage and prevent symptoms with bath gels, emollients, or moisturising creams. Initially, patients were overwhelmed by routines, but as they got older and became responsible for their self-management, they felt more confident and in control. This phase was when most caregivers and patients truly felt in control, yet it took some time for patients to get used to emollients and for caregivers to gain confidence in their child’s ability to self-manage.

Flare cycles

Caregivers addressed flares with prescribed medicated creams and skin hydration routines, seeking medical help only if necessary. Although experienced, both patients and caregivers felt frustrated when the flare became unmanageable, having to seek consultation from HCPs and to begin a new trial-and-error process to identify an effective topical treatment. Experienced caregivers may discontinue medication once they observe visible improvement in the skin. Patients felt frustrated upon a new flare, while caregivers experienced emotional fatigue.

Impact of Atopic Dermatitis on Patients and Caregivers

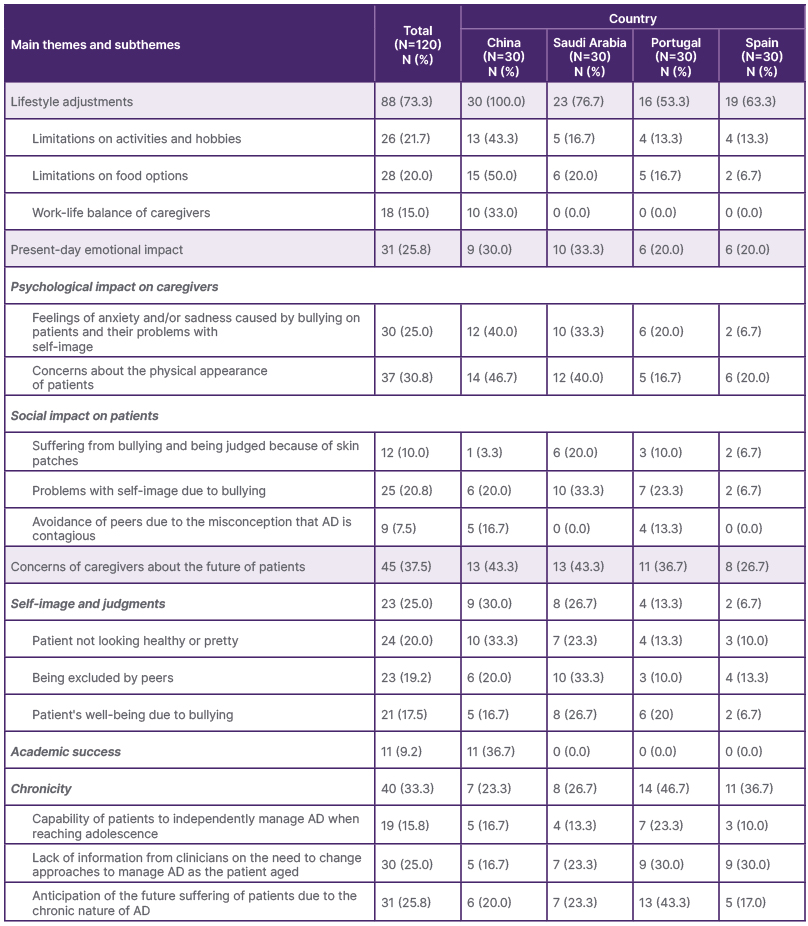

The authors identified the main themes and subthemes impacting patients with AD and their caregivers, and these are summarised in Table 2. The most common themes were lifestyle adjustments, present-day emotional impact, and concerns about the future.

Lifestyle adjustments

Patients

Most participants (all of them, in the case of China) found that lifestyle adjustments due to AD were challenging both physically and emotionally. Lifestyle adjustments were greatly stemming from limitations on activities and hobbies, which affected a considerable number of participants, especially in China (Table 2). These limitations involved avoiding environmental triggers (i.e., heat, cold, humidity, dryness) and prohibiting patients’ activities, such as swimming to avoid pool chemicals, or playing football or going to dance classes to avoid sweat. Many patients also faced limitations on clothing, make-up, and food options imposed by caregivers. Illustrative quotes on this topic can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2: Main themes and subthemes identified as impacting patients with atopic dermatitis and their caregivers in the total study population.

AD: atopic dermatitis.

Caregivers

Lifestyle adjustments also affected caregivers. Many Chinese caregivers, all of them mothers, reported having their work-life disrupted or completely giving up work due to their child’s condition. However, this issue was not identified in Saudi Arabia, Portugal, or Spain (Table 2).

Furthermore, limitations on activities and food also had an impact on caregivers. For example, placing restrictions on children’s activities and hobbies made many Chinese caregivers feel inadequate as parents due to not being able to provide a well-rounded childhood experience. For their part, some Saudi Arabian caregivers, all of them mothers, reported that restricting their children’s food negatively impacted their sense of motherhood. However, Portuguese and Spanish caregivers did not express being affected by the limitations imposed on their children.

Present-day emotional impact

Approximately a quarter of the participants reported that AD had a negative impact on the emotional well-being of both patients and caregivers. Illustrative quotes on this topic can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

Patients

The emotional impact on patients encompassed bullying and judgement by school peers and family members because of visible skin patches, problems with self-image, especially during flare-ups, and avoidance from peers due to the misconception that AD is contagious. Saudi Arabian participants reported experiencing the highest levels of bullying and struggles with self-image, while Spanish participants appeared to be the least impacted by these issues. The proportion of female patients suffering from bullying was approximately seven times that of male patients. The avoidance of peers was only reported by Chinese and Portuguese participants (Table 2).

Caregivers

The psychological impact on caregivers included feelings of anxiety and/or sadness associated with the patient being bullied and having a lowered self-image, along with concerns about the physical appearance of patients. Both issues mainly affected Chinese and Saudi Arabian caregivers. Notably, while judgement was primarily passed by school peers in most countries, in Saudi Arabia, many mothers reported that judgments on how females physically looked were mainly passed on by relatives.

Concerns about the future

Caregivers

More than a third of caregivers expressed concern about the future of their children living with AD, which also negatively affected their current emotional well-being, especially in China and Saudi Arabia, where almost half of the caregivers expressed being affected. Regarding self-image and judgments, some caregivers thought that their children did not look healthy (both male and female patients) or pretty (only female patients), feared their children would be excluded by their peers, making the patient feel self-conscious, and reported being worried about their children’s mental well-being due to bullying. These concerns were expressed much more by caregivers in China and Saudi Arabia than by caregivers in Portugal and Spain.

The question of academic success was brought up several times by Chinese caregivers. Many of them thought that not being able to participate in certain hobbies or family activities, as well as the impact of lack of sleep due to AD, would negatively affect their children’s future academic success.

Regarding chronicity, approximately one-third of caregivers across all countries did not perceive AD as a chronic condition until their child reached adolescence, and this realisation instilled a sense of concern and apprehension. In this regard, some caregivers expressed concerns about their child’s capability to independently manage AD and adopt effective self-care and hygiene practices. Additionally, many caregivers from all countries said their doctor did not provide information on the need to change topical treatments or introduce stress-management techniques as children aged. Similarly, many caregivers across the countries expressed a sense of distress for their children, anticipating their future suffering due to the chronic nature of AD. This issue was especially frequent in Portugal, affecting nearly half of the caregivers (Supplementary Table 1). Illustrative quotes on this topic can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

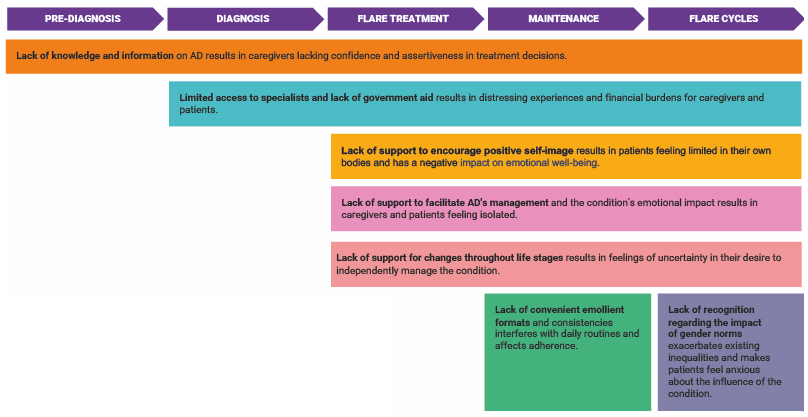

Unmet Needs Across the Care Journey

Across the AD care journey, several key unmet needs, both functional and emotional, emerged that affected both patients and caregivers (Figure 2). Illustrative quotes on the unmet needs across the care journey can be found in Supplementary Table 5.

Figure 2: Unmet needs across care journey.

Key unmet needs identified through thematic analysis of patients and caregiver interviews during each phase of AD clinical management. These unmet needs reflect participants’ experiences and highlight the multidimensional impact of AD on daily life, emotional well-being, and long-term challenges.

AD: atopic dermatitis.

Lack of knowledge and information

One significant issue was the lack of knowledge and information on AD, leading to caregivers lacking confidence and assertiveness in treatment decisions. Caregivers often confuse symptoms with allergies or environmental rash. Caregivers and patients did not receive detailed information about AD, its nature, characteristics, treatment path, or what to expect. In addition, caregivers and patients did not receive assertive information on the potential long-term effects of using corticosteroids. Often, caregivers and patients lacked comprehensive information about non-steroidal treatment options, which hindered their ability to make well-informed decisions and try alternative, less aggressive treatment approaches. Pre-teens and teenagers wanted to receive advice and information from HCPs, preferably dermatologists, to avoid flares and know how to treat them.

Limited access to specialists and a lack of government aid

Another unmet need arises from limited access to specialists and a lack of government aid, resulting in distressing experiences and financial burdens for caregivers and patients. Patients visited HCPs with unrelatable language and unwelcoming offices for young children. Caregivers often felt uncertain about the diagnosis and management plan provided by paediatricians or general practitioners, leading to a lack of reassurance. Many caregivers reported that there was a lack of government subsidies to access costly, quality skincare products.

Lack of support to facilitate atopic dermatitis management

The lack of support to help facilitate AD’s management and cope with its emotional impact resulted in caregivers and patients feeling isolated. Caregivers lacked support to motivate their children to use medication and hydrate their skin. Additional unmet needs included treatments that yielded slow results and not having other tools to control AD beyond prescribed therapies. Caregivers and patients lacked assertiveness about chosen self-management pathways, as they hardly received new information in follow-up visits and, as a result, needed comprehensive support to self-manage the condition and cope with the emotional burdens.

Lack of convenient emollients

Another challenge is the lack of convenient emollients, which interfered with daily routines and negatively affected adherence. Caregivers thought there was a lack of fast-absorbing emollients, and limited availability of smaller, portable emollient bottles added to the challenge for many families.

Lack of support to encourage a positive self-image

Caregivers thought that the lack of support to encourage a positive self-image had a detrimental effect on patients, making them feel limited by their condition and negatively impacting their emotional well-being. Patients could not participate in some active and outdoor activities. Caregivers also reported there was a lack of emotional support to deal with their affected physical appearance when they experienced a patch or flare-up.

Lack of support for changes throughout the life stages

As children with AD grew older, particularly during adolescence, caregivers reported a lack of support to help them navigate the changes in their personal care routines. Adolescents often began experimenting with cosmetics and skincare products, but they lacked guidance from HCPs on how to incorporate these products with their existing treatments. Additionally, during stressful periods such as exams, patients may experience flare-ups that worsen due to academic pressure, yet there is little support available during these life stage transitions.

Lack of recognition of gender norms

The lack of recognition regarding the impact of gender norms exacerbated existing inequalities and made patients feel anxious about the influence of the condition. Caregivers and patients were concerned about school performance, specifically with boys. In societies with strong gender differences, such as Saudi Arabia, adolescent girls and mothers were asked about their condition.

DISCUSSION

This multi-country qualitative study, conducted across Spain, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, and China, offers in-depth insights into the experiences of patients with AD and their caregivers, shedding light on how the condition affects their everyday lives.

This study reaffirms the profound burden that AD imposes not only on patients but also on their caregivers, especially parents. This study identified three main themes related to AD that reflect different dimensions of participants’ experiences and how AD significantly impacts both patients and their caregivers: lifestyle adjustments, present-day emotional impact, and concerns about the future.

Lifestyle adjustments refer to the practical changes that patients and caregivers must implement to manage day-to-day life with AD. These changes in turn shape the emotional well-being of participants, who adapt their routines and activities to control the disease. Present-day experiences also give rise to concerns about the future, related to disease progression and the potential implications of the chronic nature of the disease. The three main themes identified capture AD experiences across immediate practical challenges and long-term outlooks, underscoring how AD extends beyond physical symptoms to affect psychological, social, and economic well-being.

Lifestyle adjustments were the most common challenge reported, highlighting the extensive day-to-day burden of AD on both patients and caregivers and echoing prior research showing how AD can interfere with activities, hobbies, and dietary patterns of many patients as well as mental health, finances, and family and worklife of caregivers.13,14,18-20

Patients often avoided physical activities or outdoor exposure due to discomfort or fear of flare-ups. Limitations on activities and hobbies had a greater impact on Chinese patients, followed by Saudi Arabian, Spanish, and Portuguese patients in that order. The case of China may be explained by the fact that in recent years, there has been a trend towards children to have a greater participation in sports, particularly as a way to mitigate the overburdening of children with academic work.21,22

Caregivers, on their side, imposed dietary restrictions to manage triggers. Restricting food intake had a negative impact on many Saudi Arabian mothers, compromising their sense of being a good mother, an issue that was not identified in China, Spain, and Portugal. This difference may be explained by the cultural role food plays in both the family unit and wider Saudi Arabian society, where the cultural significance of generosity with food cannot be underestimated.23 The act of restricting food is seen as inhospitable and a blight on the family unit, contrary to what it means to be a good Muslim.24 In this context, limiting food to their children can impact mothers’ sense of identity, as well as make them the target of judgement by other mothers, family members, and society as a whole.

Caregivers in this study, especially Chinese mothers, reported work disruptions or leaving employment altogether, highlighting the socioeconomic toll and gendered impact of caregiving. In a global survey addressing the impact of AD on caregivers, it was discovered that for approximately one-third of families, their child’s AD impacted their decision to work outside the home.5 The authors’ study identified a similar issue in China: 16% of the Chinese mothers in their sample saw their worklife impacted by their children’s AD, with many having to stop work altogether. However, the authors did not identify this issue in Spain, Portugal, and Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, for Saudi Arabia, the role of mothers as housewives could also explain this result, as has been reported in other studies with mothers on maternity leave or unemployed.25 Few studies have considered the impact on caregiver work to estimate indirect AD costs.26,27 The results of this study highlight the importance of considering the sociocultural background of each country when estimating indirect AD costs on work.

Present-day emotional impact was another significant burden for both patients and caregivers. Caregivers reported anxiety or sadness, often tied to their child’s experiences of bullying, stigma, or negative self-image. This was especially pronounced in China and Saudi Arabia. Patients themselves faced emotional challenges due to bullying, social avoidance, and stigma, especially in China and Portugal, where AD was sometimes misunderstood as contagious. Xie et al.28 showed that AD could result in caregiver/child conflicts, alongside children being bullied, discriminated, and stigmatised, resulting in a traumatic life experience. Additionally, there is literature which addresses children’s feelings of being discriminated and isolated due to their skin condition in both Hong Kong and Poland, demonstrating how self-esteem and stigmatisation are central features of a patient’s life with dermatological issues.28,29 The authors’ study adds to this body of literature, showing that the prevalence of some of these issues may be context and gender dependent.

Together, these findings highlight the need for holistic AD care that addresses not only physical symptoms but also emotional well-being and social stigma.

Concerns about the future was another notable area of impact, often contributing to their current emotional distress. Caregivers feared their children might face social exclusion, mental health challenges, or academic setbacks, particularly in China, where academic achievement is highly emphasised. AD flares may impact academic success, particularly if students have to go to the doctor or the school nurse frequently or have poor attendance.30 Many caregivers, especially across Portugal, also worried about their child’s ability to manage AD independently as they aged. Across countries, caregivers expressed a lack of guidance from HCPs on evolving care strategies. These findings underscore the need for anticipatory guidance and support to help families prepare for the evolving nature of AD, as it is paramount to adapt AD impairments to each stage of life.31

This study highlights several unmet needs faced by patients with AD and their caregivers. These include a lack of knowledge and accessible information about the condition, limited access to specialists, insufficient government aid, and a lack of tools to facilitate day-to-day management. Practical barriers such as inconvenient emollients further hinder adherence. In addition, social and emotional aspects remain under-addressed. Patients often experience a lack of recognition of gender norms, limited support for maintaining a positive self-image, and minimal guidance through key life transitions such as adolescence or periods of academic stress.

To address these challenges, several strategies could be helpful. First, awareness campaigns and informational materials can help patients and caregivers feel reassured, better understand AD, identify early signs, track disease progression, and actively participate in treatment decisions. Second, enhanced training for paediatricians and general practitioners is essential to equip them with the skills needed to meet patients’ and caregivers’ expectations regarding communication, engagement, information, and treatment. Third, support beyond treatment should be prioritised through the creation of digital tools, such as mobile apps, websites, videos, and games, to facilitate routine disease management, decision-making, and patient education, as suggested in the literature.32,33 Finally, raising awareness and facilitating access to support programmes can help ease the emotional burden carried by patients and caregivers, offering both practical guidance and much-needed psychosocial support throughout the AD journey.

This study has some limitations. First, its retrospective design may have led to selection and misclassification biases. Second, the interviews were performed virtually and not face-to-face, which potentially may have increased social desirability bias and limited observation of non-verbal cues. Third, the relatively small sample size and inclusion of a limited number of countries may limit the generalisability of the findings. However, despite these limitations, the authors’ study has allowed us to deepen our knowledge of the patient and caregiver journey, understand the impact of AD on individuals in culturally diverse countries, and identify their unmet needs.

CONCLUSION

This multi-country qualitative study reveals the complex journey of patients with mild-to-moderate AD and their caregivers across diverse cultural settings. AD impacts daily life, emotional well-being, and future outlook. Key unmet needs include limited knowledge, emotional support, access to care, and self-management tools. Addressing these requires holistic, country-specific strategies that combine education, improved communication, and digital tools across life stages.