Interview Summary

While awareness of the issues facing women leading up to, during, and following the menopause has increased in recent years, it remains a condition of significant unmet need. Reasons include a stigma around asking for help, and a lack of awareness of the symptoms and associated risks among women and healthcare professionals alike. Standard medical training includes limited education on perimenopausal and post-reproductive healthcare, meaning clinicians are often ill-prepared to intervene. However, there is much that healthcare professionals, regardless of their specialty, can do to help women entering their post-reproductive years, say Rossella Nappi, Chief of the Research Centre for Reproductive Medicine and Director of the Gynecological Endocrinology and Menopause Unit at IRCCS San Matteo Foundation, University of Pavia, in Italy; and Katrin Schaudig, co-founder of the Centre for Gynaecological Endocrinology, Hormone Hamburg, Germany, and President of the German Menopause Society. Moreover, perimenopause represents an important opportunity to engage, inform, and empower women to take charge of their health for years to come. In this key opinion leader interview, Nappi and Schaudig explain the physiological changes associated with menopause, their clinical manifestations, and their associated risk factors. They talk about the need to tackle the stigma that is often attached to this phase of life, and why healthcare professionals have a duty to work with women to spot the signs of menopausal transition from an early stage. They argue that holistic care, which focuses as much on the prevention of chronic disease as it does on the treatment of menopausal symptoms, is key to ensuring women stay physically and mentally fit and healthy as they get older.A NATURAL EVENT

Menopause is the last menstruation in a woman’s life. It corresponds to the cessation of ovarian function, comprising loss of reproductive hormone production, and the irreversible loss of fertility.1 It is a natural event that occurs in all women, but Nappi said there were a “wide rainbow of possibilities” in terms of phenotypes. In Western countries, early menopause is defined as occurring between the ages of 40–45 years, and menopause before the age of 40 years as premature menopause or premature ovarian insufficiency.1,2 In some women, menopause is induced by surgical removal of the ovaries, or pharmacological interventions delivered with the aim of temporarily or permanently stopping the production of reproductive hormones.

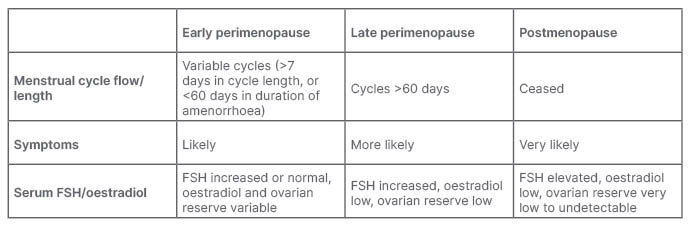

It is usually not a sudden occurrence. Women tend to enter the menopausal transition slowly, and “it can be a long journey,” said Schaudig. Perimenopause is defined as the time between the onset of menstrual irregularities and 12 months after the last menstrual period, which is the official definition of menopause.3 It tends to start between the ages of 45–55 years and, on average, lasts for about 7 years.4 Twelve months after the last menstrual period, the woman enters postmenopause.

Explaining the physiology of the process, Schaudig said that a woman’s life could be divided into three chapters: childhood, a reproductive stage, and a post-reproductive stage. At puberty, women have around 300,000 ovarian follicles.5 During this time, a feedback loop between the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the ovaries is established,6 resulting in a single follicle, containing a single oocyte, being released each month. This process is responsible for the release of reproductive hormones, including oestradiol and progesterone,7 as well as anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH).8 By the age of around 37 years, the number of ovarian follicles, which are the source of AMH secretion, will have reduced to around 25,000. As the follicle reservoir depletes, so do AMH levels, leading to an increase in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), resulting in fluctuations in hormone production and irregular cycles.5,9

“The production of sexual hormones becomes like a roller coaster,” said Schaudig. “During the perimenopause, we can sometimes see two or even three developing follicles in 4 weeks with untimely ovulations, even during menstruation. There may also be months without a complete follicle maturation at all. It means there might be periods of oestradiol deficiency, followed by periods of elevated oestradiol levels, all accompanied by an elevation in FSH, as the body tries to normalise the cycle. At the same time, the secretion of progesterone that usually takes place after ovulation is impaired, which may lead to a dominance of oestradiol and bleeding disorders.” The eventual exhaustion of the follicle reservoir leads to the almost complete depletion of oestradiol, progesterone, and AMH in the postmenopausal stage (Table 1).5,6

Table 1: Menopausal stages.5,9

FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone.

SYMPTOMS AND RISK FACTORS

Menopause symptoms vary between individuals,1 as well as the stage of transition.5 During the early stage of perimenopause, when there is fluctuating ovarian hormone production, women may experience symptoms related to oestrogen excess (such as breast tenderness, menorrhagia, migraine, nausea, or a shorter cycle length), oestrogen insufficiency, or a mixture of both.5 Oestrogen deficiency symptoms, which can include vasomotor symptoms (VMS) like hot flashes and night sweats, and urogenital symptoms like vaginal dryness, urinary tract infections, and urge incontinence, are more common in the later stages and postmenopause.10,11 In perimenopause, women may experience ‘cognitive fog’, fatigue, irritability, disturbed sleep, joint pain, anxiety/depressive moods, and loss of libido.5 Such symptoms can be insidious in nature, explained Nappi. “It is not a sleep disorder, or depression, it’s more that you just do not feel yourself; you do not feel okay,” she said, adding that some women may have the appearance of having severe premenstrual syndrome.

Such symptoms can have a significant impact of health-related quality of life and wellness, Nappi went on.12 She explained that the symptoms impacted on multiple domains of health-related quality of life, including working capacity, social activity, sport/exercise, emotional wellbeing, and pain, as well as self-esteem and self-perception.

The peri- and postmenopausal stage of life is associated with a range of evolving risk factors. Some of these are linked to changes in hormone levels, and others to simply getting older. Women may also experience iron deficiency as a result of heavy and irregular menstrual periods during the transition phase.13

Furthermore, the fall in oestradiol levels has a number of adverse metabolic effects. During the reproductive stage of life, reproductive hormones help to balance bone loss, but their depletion at menopause can contribute to the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. Women tend to experience increases in insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia, and endothelial dysfunction, as well as an increase in abdominal fat deposition.14 Such changes increase the likelihood of conditions, including cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and Type 2 diabetes.5,14 The CVD-protective effect of oestrogen is lost around 10 years after the onset of menopause.14 Cancers, both age- and hormone-related, are another important consideration. While menopause is not directly related to cancer, the risk increases with age15 and obesity,16 explained Schaudig. With CVD and cancer being the leading causes of mortality worldwide,17 she went on, understanding and working to mitigate such risks, is key.

Nappi added that the age of onset of menopause was another element to the risk profile. Early menopause, for example, is associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer, but increased risks of premature osteoporosis, CVD, and premature death.2

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS

Traditionally, perimenopausal and postmenopausal healthcare has not received the attention it deserves, due in part to the stigma of the condition and of asking for help. Menstrual bleeding is often a symbol of femininity for women, and many perceive their inability to cope with symptoms on their own as a sign of weakness, said Nappi. “Sometimes, women do not want to ask for help because they do not want to be judged,” she added.

High-profile awareness campaigns have, in recent years, gone some way to raising awareness and dispelling the stigma, but there is still work to be done. Schaudig said women in their mid-40s were often shocked when she told them they could be perimenopausal. “They say they are too young for that. They think that being menopausal means to be grumpy, and unattractive, and that it is synonymous with being old,” she said. While it is, of course, still possible for women going through perimenopause to become pregnant, “it can be hard for women to accept they may not be fertile anymore,” she went on.

However, menopause does not mean “the end,” said Nappi, describing it instead as the “start of a new era.” “Menopause is a natural part of being a woman. Longevity has increased so much that women of this age are active members of society, they have jobs and young children. They should not be ashamed of menopause symptoms, and they need to be aware that some of them will not just go away; in fact, they may go on for a long time. So why should they have to suffer?”

Yet, even when women do ask for help, it may not always be forthcoming. Healthcare professionals tend to receive limited training on post-reproductive health, meaning they do not always feel qualified to intervene, explained Nappi and Schaudig. As such, many will wait until 12 months after the last menstrual bleeding, i.e., until the person has entered the postmenopause period, before offering advice or treatment. Nappi said: “This is a common but important mistake. You need to start taking care of your patient as soon as you realise that they are experiencing perimenopause.” Early intervention, both in terms of helping women to cope with the direct symptoms and to manage their future health, is critical.

THINK PERIMENOPAUSE

Nappi advised healthcare professionals to “think about perimenopause,” and ask about bleeding cycles in all women over 40. It is important to note, she went on, that they may present with symptoms such as mood or sleep disturbances, having no idea they could be related to the perimenopause.

According to the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) staging system, if the length of a woman’s consecutive cycles differs by 7 days or more over at least 10 months, she is likely to be in the early stage of perimenopause.18 In this phase, FSH may still be in the normal range, which may lead to the incorrect assumption that the woman has not yet entered early perimenopause. AMH levels are already low in this phase, and so is the antral follicle count.18 The STRAW system further defines late stage perimenopause as amenorrhoea of 60 days or longer, with a now increased FSH level, increased variability in cycle length, extreme fluctuations in hormonal levels, and the increased prevalence of anovulation.18

Hormonal tests, however, are not always recommended to diagnose menopause, particularly in those aged over 45 years.5 The 2023 Practitioner’s Toolkit for Managing Menopause, which has been endorsed by the International Menopause Society (IMS), explains the tests are uninformative in those using systemic hormonal contraception that suppress ovulation, have a progestin intrauterine device, or have been prescribed progestogen following an endometrial ablation, for example.5

The toolkit states that hormonal measurements “may be useful” in women aged between 4 0–45 years, and amenorrhoeic women with subtle or fluctuating symptoms, such as mood changes, with no or few VMS.5 However, it also notes that a single observation of normal FSH and oestradiol would not exclude perimenopause, a period during which hormone levels are known to fluctuate.5 It recommends hormonal testing when there is a suspicion of premature ovarian insufficiency (menopause before the age of 40 years), and explains that elevated FSH and low oestradiol on at least two occasions between 4–6 weeks apart is indicative of premature menopause.5

Depending on clinical assessment, healthcare professionals will also need to exclude other causes of amenorrhoea, such as pregnancy, hypothalamic amenorrhoea, hyperprolactinaemia, or thyroid disease.5 In those experiencing fatigue, changes in mood, and hot flashes, Nappi also recommended measuring thyroid stimulating hormone for thyroid disease, haemoglobin for iron deficiency, and fasting blood glucose for Type 2 diabetes.5

“It is important that healthcare professionals recognise when women are in the perimenopause so that they can offer help, and at least give them a clue as to what is going on,” said Schaudig. While some issues will require specialist gynaecological input, there is much that can be done in primary care to help women remain physically and mentally healthy as they transition to postmenopause. Symptoms such as vaginal dryness, for example, “can, and should” be treated relatively simply. Just being able to reassure women that symptoms, such as cognitive fog or low mood, are part of the process, rather than signs of a more serious underlying condition like dementia or depression, can be critical to their wellbeing, Nappi and Schaudig agreed.

HEALTHY AGEING

Nappi referred to this period as a “golden moment” to engage women to focus on primary prevention. Schaudig agreed. “It is the perfect opportunity to ask women to reflect on what they want from the next, often longest, stage of their lives,” she said, adding that most will answer that they want to live long and healthy lives. “Explain that there is nothing to be scared of, but that they are at a turning point; that the reproductive hormones that have protected them from some chronic conditions for the last 35 years or so are no longer there,” Nappi went on.

She highlighted a care pathway from the European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS), which recommends a battery of screening and investigations aimed at assessing an individual’s risk of long-term health conditions.3 Smoking status, diabetes history, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels, as well as the family history can be used to estimate CVD risk, while BMI and waist-to-hip ratio are useful for predicting the risk of metabolic syndromes.3 Not only will this information help to inform prevention strategies, but it will also guide any decisions on menopausal hormone therapy (MHT).3

Peri- and postmenopausal women should also be stratified for fracture risk, using, in those over the age of 40 years, the FRAX® calculator (University of Sheffield, UK).3 Thresholds for bone mineral density assessment by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry vary by country.3 In the UK, for example, all postmenopausal women >65 years of age should be screened.3 Clinicians, Nappi said, should follow their own national guidelines. The EMAS pathway also states that older postmenopausal women can experience an age-related decline in muscle strength and mass, and decreased physical performance.3 Handgrip strength, gait speed, and the SARC-F questionnaire are useful sarcopenia evaluations, she went on.3

Clinicians have an important educational role to play, said Schaudig, referencing a 2004 survey that found 35% of women identified breast cancer as their most important health threat,19 despite the condition carrying survival rates of up to 93%.20 “The data is quite old now, but I think it still holds true,” Schaudig said, adding that while breast cancer was the most common cancer in women, mortality was low. Conversely, just 13% of survey respondents thought they would die from CVD, despite it being one of the leading causes of death in men and women, worldwide.17

Based on these assessments, healthcare professionals can engage, inform, and empower women to manage their long-term health, both doctors argued. “If you are around 50, you may live until you are 90 or 100, which means you still have 40 or 50 years,” said Schaudig. It makes it a good time for women to consider, with their healthcare professional, what they can do to improve their quality of life, and reduce their risk of conditions such as CVD and cancer. “There are all kinds of things we can do in terms of lifestyle: physical exercise, nutrition, minimising alcohol, and stopping smoking.” Clinicians should also encourage women to undergo regular blood pressure checks and engage with national cancer screening campaigns, including for breast and colon cancer,5 which account for more than 40% of malignancies in women across Europe.21

Prevention advice, Nappi argued, should be “first-line.” “We should empower women by informing them of the best things they can do around the time of menopause,” she said.

PERI- AND POSTMENOPAUSE MANAGEMENT

Managing menopause symptoms starts with a conversation about which are the most burdensome, both Nappi and Schaudig agreed. “I call it the fairy godmother question,” said Schaudig. “I ask, ‘if you had one wish, which symptom would you make disappear?’ Then, ‘what if you had two wishes?’ and so on, until we have a list.” This, combined with a holistic understanding of women, their lifestyle, and their goals, will help to build a treatment plan.

According to the 2023 Practitioner’s Toolkit for Managing Menopause, the most robust menopause clinical practice guidelines support MHT as the most effective treatment to alleviate VMS, and individual risk factors will guide selection of the most appropriate approach.5 “When we think that the lack of hormones is the reason for many of these symptoms, it is quite logical to at least think about replacing these hormones,” said Schaudig. “However, this is tricky in the perimenopausal period, when the levels are going up and down.”

For some perimenopausal women, combined hormonal contraceptives can be useful for regulating hormonal cycles and, therefore, relieving symptoms.5 However, it will not be suitable for those who wish to become pregnant, and the appropriate type of agent will depend on the individual’s risk factors.5 For women with contraindications for combined hormonal contraceptives, progestin-only pills, in combination with transdermal oestradiol during periods of oestrogen depletion symptoms, can be useful. Bleeding disorders can be treated with levonorgestrel intrauterine devices.

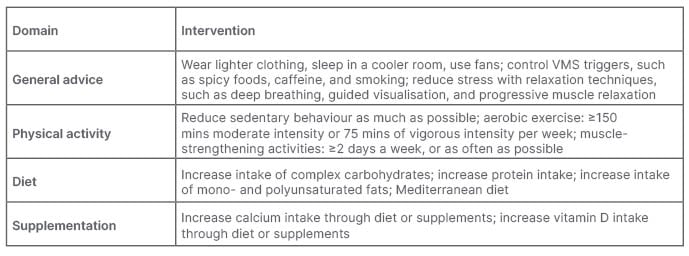

Non-hormonal interventions often mirror those employed for the prevention of chronic conditions, and include a focus on diet and exercise, as well as removing VMS triggers, such as caffeine and alcohol (Table 2). Being overweight and smoking are risk factors for VMS, for example, so encouraging weight reduction and smoking cessation can help.2,5 Exercise, yoga, mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques, and relaxation may improve sleep, and, by extension, fatigue, mood, and general wellbeing.2 Food supplements,1,2 such as black cohosh, calcium, and vitamin D, may have a “mild effect,” said Schaudig. Cognitive behavioural therapy may also be useful for VMS, and may also provide benefits in terms of sleep and mood.1 Gabapentin, as well as some antidepressants, such as venlafaxine and paroxetine, can sometimes be efficacious.2

Table 2: Lifestyle advice for the management of menopausal symptoms, and for prevention of chronic disease associated with ageing and the menopause.3

Nappi said there were also a number of novel non-hormonal agents for VMS, one of which has now been approved by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration).22,23,24,25 These neurokinin B receptor antagonists target the KNDy neurons, which are involved in the release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone and temperature regulation. 22,23,24,25 This new class of drugs will help those women who are considered unsuitable for MHT, or for those who are simply averse to its use, said Nappi.

MAKING A DIFFERENCE

Summing up, both doctors offered their topline advice to clinicians. “Don’t miss the early signs of menopause; don’t leave women to their fate,” said Schaudig. “At the beginning there will be cycle irregularities, mood swings, a lack of concentration, depressive mood, and sleeplessness, but without hot flashes. These come later.” Nappi said they should not miss any opportunity to talk about menopause and healthy ageing, because “it will always be time well spent.”