Meeting Summary

Given the progressive nature of ulcerative colitis (UC), Prof Colombel argued that effective therapy is warranted early in the disease course, especially for patients judged at a high risk of colectomy. To slow disease progression clinicians should aim for complete recovery or absence of inflammation in the gut mucosa. This goal has recently been recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) who advised that endoscopy should be used in conjunction with histology for the assessment of mucosal healing in UC.

Considering remission in UC, Prof Feagan explained that while there is clear evidence that endoscopic remission is associated with better outcomes, challenges remain in achieving remission with current agents. Studies show utility for incorporating histopathological activity into clinical trials, but there are concerns regarding the lack of agreement among pathologists. Two newly validated indices for evaluating histologic disease activity in UC (Robarts Histopathology Index [RHI] and Nancy Histopathology Index) open the way for histopathology to be introduced in early drug development.

Prof Schreiber reviewed vedolizumab, a gut-selective α4β7 integrin antagonist recommended by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) guidelines as a first-line biologic therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe UC. Data from clinical trials showed that vedolizumab has the greatest efficacy in anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-naïve patients and early in the disease course. Histologic healing, reported in >50% of UC patients with endoscopic remission taking vedolizumab, is likely to be a new endpoint in clinical trials. Vedolizumab has a favourable risk-benefit profile, with >77,382 patient years of post-marketing exposure worldwide.1

Resetting Expectations for Therapy in Ulcerative Colitis

Professor Jean-Frédéric Colombel

For a long time it has been known that UC has a variable course, with some patients displaying chronic intermittent symptoms, some chronic continuous symptoms (a type of malignant UC), some with a flat disease course at the beginning with sudden flares, and some that show no disease activity after initial flares. The Danish IBSEN study, which followed 423 UC patients for 10 years, found that 1% showed increases in symptom intensity, 6% in chronic continuous symptoms, and 37% in chronic intermittent symptoms.2 The study revealed over half of UC patients had an unfavourable disease course that needed to be controlled.

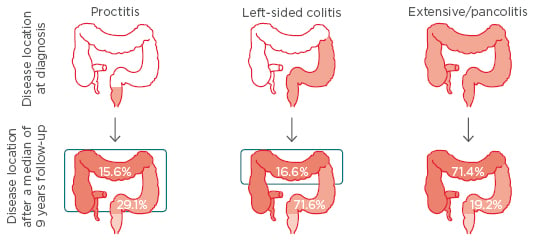

Like Crohn’s disease (CD), UC is a progressive condition. The Swiss Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Cohort study, which followed 918 UC patients, showed that in patients with disease limited to proctitis at diagnosis, 29.1% had their disease extend into left-sided colitis and 15.6% to pancolitis after a median of 9 years (Figure 1).3

Figure 1: Ulcerative colitis as a progressive disease: Proximal extension over a median of 9 years.3

Results from the Swiss IBD Cohort Study (N=918).

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

The extent of colonic involvement in UC has implications for the severity/activity of the disease, the need and type of medication for therapy, the rates of colectomy/hospitalisation, the risk for cancer, and mortality.

Significant associations have been found between an increased width of the presacral space (a diagnostic indicator of pelvic and rectal pathology) and disease duration, with one study showing UC patients with presacral widths >16 mm had a mean disease duration of 10.5 years compared to 4.5 years for patients with widths <16 mm.4,5 Indeed, computed tomography (CT) scans suggest presacral morphological changes arise from the proliferation of perirectal fat and fatty infiltration of the submucosal layer.4 Other consequences of long-term inflammation include strictures, pseudopolyposis, bridging fibrosis, dysmotility, and altered colonic permeability.4

Several surveys indicate that the effects of UC can be underestimated, with disconnects between doctors and patients. For example, one USA survey (involving 451 UC patients and 300 gastroenterologists) revealed that 21% of patients felt their symptoms to be “completely or mostly under control” compared with 48% of physicians.6 Once again, 42% of patients said symptoms caused disruption to daily activities compared with 17% of physicians.

In recent years, the risk of colectomy in UC has plateaued. A comparison of three cohorts from the Dutch IBDSL study showed that the rates of early colectomy decreased between the first (1991–1997) and second cohorts (1998–2005), but no further decrease was found for the third (2006–2010).7

Cohort studies deliver more promising news for colorectal cancer (CRC) risk. A Danish nationwide study, following 47,374 IBD patients over 30 years, showed that while CRC risk was increased for UC patients diagnosed in the 1980s, the current risk was the same as people without IBD.8 Increased CRC risk however persists for certain subgroups of UC patients, including those who are older, have primary sclerosing cholangitis, or severe inflammation. One study showed significant correlations between colorectal neoplasia and inflammation (odds ratio [OR]: 2.54 for each one-point increase in colonoscopical inflammation scores).9

Taken together, such data indicate a need to ‘reset’ therapeutic expectations for UC. Effective therapies, said Prof Colombel, should be initiated early in the disease course, especially for patients at risk of fast progression and colectomy, with the objective of achieving and maintaining complete recovery of inflammation in the colonic mucosa long-term.

More data is available for CD than UC to demonstrate how better outcomes are achieved when biological therapies are initiated early in the disease course. For example, in CD for patients with disease duration <1 year at study entry10,11 >70% achieve remission while for patients with disease duration >7 years at entry, only around 40% achieve remission.12,13 Similar studies exploring disease duration and biological therapy effectiveness are now needed in UC, Prof Colombel suggested.

The heterogeneity of UC makes it important to understand which patients are at greatest risk of colectomy, who merit receiving intensive treatment from the outset. The Norwegian IBSEN cohort study, a multivariate analysis of 464 UC patients (including 49 who underwent colectomy), revealed that the extent of disease, age, need for systemic steroids, and C-reactive protein (CRP) biomarkers/or erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESRs), were all independently associated with colectomy risk.14 From this, Solberg and colleagues calculated that the highest risk of colectomy occurs in a patient aged <40 years with extensive colitis, ESR/CRP ≥30, and systemic steroids at diagnosis, with a 40.1% risk of undergoing colectomy within 10 years.

Last year a literature review identified predictors for proximal disease extension (disease progressing to more extensive UC) including: delays in diagnosis >6 months, a family history of IBD, a young age at diagnosis, disease severity at onset, a need for steroids at diagnosis, a poor response to therapy (>3 relapses per year), and concurrent primary sclerosing cholangitis.15

The latest ECCO guidelines, published in 2012, state that the goal of UC maintenance therapy is to maintain both clinically and endoscopically defined steroid-free remission.16 Such guidelines raise important questions of whether clinical and endoscopic remissions represent adequate treatment targets in UC. Data from an observational multicentre study by Prof Colombel shows that despite being judged as endoscopically healed (Mayo Clinic endoscopic subscores [MCSe]), around 20% of patients experience clinical symptoms, including rectal bleeding and increased stool frequency.17 Furthermore, a chart review of 152 IBD patients judged as being in clinical remission undergoing surveillance colonoscopy showed 31% (n=47) had no signs of inflammation during endoscopy and 49% of the remaining patients (n=105) had endoscopic and/or histologic inflammation.18 Together, such data suggests many UC patients considered to have achieved clinical remission still have evidence of active disease.

A recent observational multicentre study by Prof Colombel showed that even among UC patients with the most stringent criteria for endoscopic healing (MCSe: 0) 9% had a stool frequency score of ≥2 and 3% had rectal bleeding scores >2.17

Such data suggest that while endoscopical healing shows good correlations with rectal bleeding, the relationship may not be so clear for stool frequency. Indeed, discrepancies may exist between inflammation and clinical symptoms, with the patient’s actual experience differing markedly from endoscopy and histology findings. Indeed, endoscopy and histology remission may not represent the final answer. To slow UC disease progression there is a need to aim for complete recovery, or absence of inflammation, in the long term in the colonic mucosa. In August 2016, the FDA recommended that in UC, “endoscopy should be used in conjunction with histology for an assessment of mucosal healing”.19 Undoubtedly, when this new recommendation is incorporated into clinical trials it will raise the bar for IBD drugs.

Remission in Ulcerative Colitis: Has it Been Achieved and for How Long?

Professor Brian G. Feagan

Regarding the definitions for UC remission, Prof Feagan said “the devil lies in the detail”. Currently, three definitions for UC remission exist: clinical, endoscopic, and histopathological. A study by Higgins et al.,20 published in 2005, showed high correlations between clinical and endoscopic remissions in UC, leading many clinicians to believe there was no need to worry about endoscopy. This, explained Prof Feagan, was a false message.

While the two non-invasive indices correlate well with the invasive St Mark’s Index (simple clinical colitis activity index [SCCAI]: 0.86; Seo index: 0.70); the correlation was not nearly so high for the Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index (UCDAI) index, which takes into consideration clinical bleeding and stool frequency. One concern is that terms used in clinicians’ endoscopy reports are vague (e.g. friability and granularity), which results in high inter-observer variability.

The latest ECCO statement on the diagnosis and management of UC incorporates endoscopic findings into treatment success definitions, although no endoscopic feature is specific for UC. The statement suggests: “the most useful endoscopic features of UC are considered to be continuous and confluent colonic involvement with clear demarcation of inflammation and rectal involvement”.16 The statement continued: “Endoscopic severity of UC may be best reflected by the presence of mucosal friability, spontaneous bleeding, and deep ulcerations”.16

For the STRIDE programme, a consensus steering committee of 28 IBD specialists agreed the definition for UC remission should be a combination of clinical/patient reported outcomes (including resolution of rectal bleeding and diarrhoea/altered bowel habits) and endoscopic remission (defined as a MCSe: 0–1).21 It is noteworthy, said Prof Feagan, how new clinical definitions of UC resolution mirror regulatory definitions. Gastroenterologists, he added, may need to justify the need for endoscopy to health payers.

Notably, STRIDE does not advocate faecal calprotectin, CRP or cross-sectional imaging as adjunctive measures of disease activity. With studies showing faecal calprotectin to be 90% sensitive and 90% specific for detecting endoscopic disease in UC, clinicians must consider whether 10% is an acceptable rate of error in making treatment decisions.

Endoscopic remission is important in UC because a large number of studies have demonstrated that the achievement of mucosal healing is associated with better outcomes. First, a Norwegian population-based cohort study of 513 UC patients (diagnosed 1990–1994) showed mucosal healing in UC was significantly associated with a low risk of future colectomy (p=0.02).22 Second, an Italian study of 157 moderate-to-severe newly diagnosed UC patients showed lack of mucosal healing following corticosteroid treatment (defined by endoscopy) was associated with negative outcomes at 5 years, including colectomy (p=0.0191), immunosuppressant therapy (p<0.0001), systemic relapse (p<0.0001), and hospitalisation (p=0.0001).23 Finally, a case-control study matching patients developing colorectal neoplasia (n=68) with two control patients from the same cohort (n=136) showed highly significant correlations between the risk of colorectal neoplasia and colonoscopical inflammation score (OR: 2.54; p=0.001) and histologic inflammation score (OR: 5.13; p<0.001).9

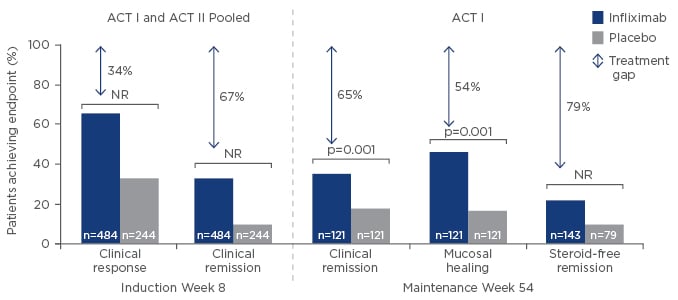

While there is clear evidence that mucosal healing is beneficial, challenges remain in achieving and maintaining remission. Pooled data from the Active UC Trials (ACT I and ACT II) showed that even among patients randomised to infliximab, 34% do not achieve a clinical response and 67% do not achieve clinical remission (Figure 2).24 The same holds true for adalimumab, with the ULTRA I study showing at induction Week 8, 45% of patients randomised to adalimumab did not show a clinical response.25 Furthermore, ULTRA II showed that after 54 weeks of maintenance therapy, 75% of patients randomised to adalimumab did not achieve mucosal healing.26 Even for the most effective therapies there is room for improvement.

Figure 2: What is the treatment gap?24

Infliximab efficacy data in UC.

UC: ulcerative colitis; ACT: Active UC Trials; NR: not reported.

Step-Care, a therapeutic pyramid with 5-aminosalicyclic acid (5-ASA) at its base followed by corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, biologics, and surgery at the top, still has a place in UC.16 5-ASA drugs are highly effective for induction and maintenance in mild-to-moderate disease; corticosteroids are also effective for short-term induction. However, many clinicians are now moving away from azathioprine to TNF antagonists and more recently, vedolizumab.

In CD, studies show the earlier and more frequent use of immunosuppressants and biologics to be associated with reduced rates of surgery.27 The basic paradigm of UC treatment has for the most part remained intact. Traditionally, UC is perceived as a benign, more forgiving disease than CD, resulting in therapy delays. The SUCCESS study, which showed that UC patients benefit from combination treatments, suggests that such views are no longer appropriate.28 SUCCESS showed that mucosal healing at Week 16 occurred in 62.8% of patients receiving the combination of infliximab/azathioprine, compared with 54.6% receiving infliximab (p=0.295) and 36.8% receiving azathioprine monotherapy (p=0.001).28 Corticosteroid-free remission at Week 16 was achieved by 39.7% of patients receiving infliximab/azathioprine, compared with 22.1% receiving infliximab alone (p=0.017), and 23.7% receiving azathioprine alone (p=0.032).

Risk of serious infection has been a major factor limiting the use of anti-TNF-αs. The TREAT™ Registry, which followed 6,273 CD patients >5 years, showed factors predisposing individuals to serious infection, including disease activity (hazard ratio [HR]: 2.239), narcotic analgesics (HR: 1.980), prednisone (HR: 1.571), and infliximab (HR: 1.431).29 However, if therapies help patients achieve remission and stop taking steroids, Prof Feagan explained that this was likely to offset increased risks leading to a neutral infection situation.

Turning to the future, Prof Feagan explained that US regulatory authorities are considering incorporating histopathology into remission definitions for drug approval. Evidence for histopathology comes from several studies, including the finding that in 1 in 129 patients with extensive UC, CRP levels >23 mg/L at diagnosis are predicted to have subsequent surgery (p=0.02).30 Faecal calprotectin can also be used, with one study showing levels to be significantly lower in UC patients judged to have inactive disease compared to mild, moderate, and severe disease.31

Current research suggests that histopathology may prove dominant over endoscopy as a marker for prognosis. A study following 91 patients for a median of 72 months, showed that histologic remission predicted reduced rates of hospitalisation, whereas endoscopic remission did not.32 Also, a univariate analysis of a single-centre cohort study in 418 UC patients demonstrated significant relationships between histologic inflammation and progression to advanced neoplasia.33

Such compelling data begs the question why histopathological activity has not already been introduced to clinical trials? Prof Feagan explained the reasons included: a lack of validated instruments, disagreement among pathologists in rating inflammation, and sampling errors. UC is a ‘patchy’ disease, making it possible to take two adjacent biopsies and achieve different results. Such variation was one of the reasons the STRIDE guidelines did not incorporate histopathology into its definition of remission.21

Recently, two new instruments have been developed for evaluating histologic disease activity in UC: the RHI34 and the Nancy Histological Index.35 Since both are well validated and sensitive to change,it is likely they will soon be introduced for early drug development. He concluded that endoscopic assessment is reliable and has prognostic value, but that histologic remission was the “new frontier” and may better predict long- term outcomes in UC.

Anti-TNF-αs are effective for the treatment of UC, but a sizeable portion of patients may not achieve adequate induction efficacy or maintain long-term clinical remission and mucosal healing.24,26 Early intensive treatment with anti-TNF-α and immunosuppressant combination therapy may improve outcomes, but there are safety issues with their long-term use.8,9 Efficacious and well-tolerated therapy is needed for early treatment to achieve mucosal healing of UC in the long term.

Meeting Expectations for Therapy: Do Gut-Selective Biologics Deliver?

Professor Stefan Schreiber

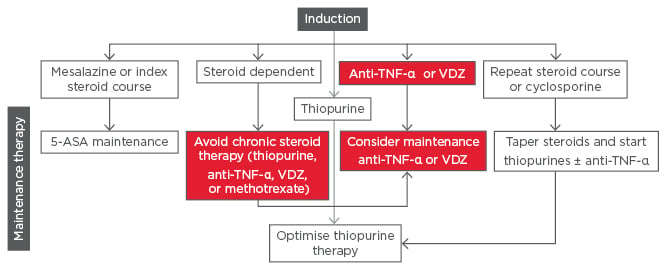

Starting his presentation, Prof Schreiber explained the gut-selective mechanism of action of vedolizumab. α4β7 integrin (a cell surface glycoprotein expressed on circulating B and T lymphocytes) interacts with the mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) on the intestinal vasculature. Vedolizumab is a humanised monoclonal antibody that specifically recognises the α4β7 integrin blocking gut lymphocyte trafficking, leading to reduced intestinal inflammatory responses.36,37 The ECCO 2016 Guidelines position vedolizumab as a first-line biologic for use in patients with moderate-to-severe UC (Figure 3).

Figure 3: ECCO Guidelines 2016 for Vedolizumab – First-line biologic for moderate-to-severe UC.51

5-ASA: 5-aminosalicyclic acid; EL: evidence level; TNF: tumour necrosis factor; UC: ulcerative colitis; VDZ: vedolizumab.

The GEMINI 1 trial led to the strong recommendation for vedolizumab inclusion within the guidelines.38 For the induction therapy at Week 6, a total of 106 of the 225 patients receiving vedolizumab (47.1%) and 38 of the 149 patients receiving placebo (25.5%) had a clinical response (p<0.001). A total of 38 patients receiving vedolizumab (16.9%) and 8 receiving placebo (5.4%) had clinical remission (p=0.001). Rates of mucosal healing were 40.9% (92 of 225 patients) with vedolizumab and 24.8% (37 of 149) with placebo (p=0.001). For the maintenance therapy part of the trial (52 weeks), patients who responded to vedolizumab at Week 6 were randomly assigned to continue receiving therapy every 4 (n=125) or 8 weeks (n=122) or switch to placebo (n=126). Results of maintenance at Week 52 showed 41.8% of patients who continued to receive vedolizumab every 8 weeks and 44.8% of patients who continued to receive vedolizumab every 4 weeks were in clinical remission, compared to 15.9% who switched to placebo. The high rate of steroid-free remission was particularly noteworthy and was observed in 31.4% of patients who received vedolizumab every 8 weeks, 45.2% of those treated every 4 weeks, and 13.9% who received placebo.38,39

Real-world data in UC confirm the benefits with vedolizumab seen in clinical trials. A meta-analysis of studies reporting vedolizumab effectiveness over 1 year, involving 1,714 patients from 98 studies (UC: 704, CD: 1,010), showed clinical remission was achieved in 24% at Week 6, 32% at Week 14, 31% at Month 6, and 51% at Year 1.40 Furthermore, the study, presented by Prof Schreiber at ECCO 2017 showed steroid-free remission in 14% at Week 6, 26% at Week 14, 31% at Month 6, and 48% at Month 12. He said that the data pointed to excellent maintenance capabilities for vedolizumab.

Focussing on early treatment with vedolizumab, Prof Schreiber said that there is need to select patients who do best on this treatment. Another study showed that patients with extensive colitis (E3) were more prone to colectomy than patients with non-extensive colitis (E1, E2), at all timepoints following diagnosis.41 Treatment of early disease is therefore key to prevent complications, he argued. While there is not yet data in UC, several studies on CD indicate that disease duration is an important determinant of the chance of treatment success. Anti-TNF-α therapy is more effective started in early disease (Step-Up Top-Down,42 SONIC,43 GETAID44) than later disease (CHARM,13 ACCENT I12). Such data suggests anti-TNF-α therapy should be started at the front end of the disease.

Data from GEMINI I in UC patients show anti-TNF-α naïve patients do better than anti-TNF-α failures regarding clinical responses at Week 6, and clinical remission at Week 52 for Week 6 responders.45 Such results speaks for higher chances of success when vedolizumab is the first-choice use. A post hoc analysis of GEMINI I, presented at ECCO 2017,46 showed that in patients who achieve remission at Week 14 (defined according to partial MCSe and rectal bleeding sub score of 0), sustained remission was maintained at Weeks 26, 38, and 52. Notably, anti-TNF-α naïve patients did better than those who had already experienced failure on anti-TNF-αs. Prof Schreiber said that sustained remission should be considered a major goal, because it meant the patient would be in remission at all timepoints.

Next, Prof Schreiber considered the impact of vedolizumab on complete healing of the mucosa. A post hoc analysis of GEMINI I showed while endoscopic healing (MCSe: 0 or 1) was achieved in 56% of patients receiving vedolizumab (every 4 weeks), 51.6% of patients receiving vedolizumab (every 8 weeks), and 19.8% of patients receiving placebo (who had received vedolizumab for up to 6 weeks).38 A completely normal mucosa (MCSe: 0) was achieved in only 33.6% of patients receiving vedolizumab (every 4 weeks), 28.7% (every 8 weeks), and 8.7% receiving placebo (who had received vedolizumab for up to 6 weeks).39

Real-world data from the US VICTORY Consortium, presented at ECCO 2017, showed the number of prior anti-TNF-α agents used in UC was associated with incremental reductions in patients achieving mucosal healing (HR: 0.697).47 Increased efficacy in real-world settings may relate to better patient selection and use of co-therapies, suggested Prof Schreiber. Histologic healing, requiring complete recovery of the colonic mucosa with absence of inflammation or structural changes, represents a new endpoint for UC. Potential benefits include patients being more likely to be symptom-free, and reduced risks of relapse, CRC, and surgery or hospitalisation.32,48

Although mucosal healing is undoubtedly an important goal, it is only a starting to be incorporated as an endpoint in clinical trials.

The latest data presented at ECCO 2017 suggest that vedolizumab delivers long-term benefits. Of the 68 patients in the GEMINI open-label extension study with data at Week 248, 98% had a clinical response and 90% were in remission.49 Five-year safety analysis of continuous vedolizumab treatment showed no increase in the incidence of adverse events over time. Of interest, the exposure-adjusted incidence rates for infections were lower with vedolizumab than placebo, and serious infections showed the same rate with vedolizumab as placebo.50 Prof Schreiber suggested this was likely to be due to vedolizumab bringing IBD under control, as IBD itself is a risk factor for infection. Notably, as of November 2016, vedolizumab has 77,382 patient years of post-marketing exposure worldwide.1