BACKGROUND AND AIMS

As many as 250,000 Canadians are living with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection,1 and specific populations, such as people who use drugs (PWUD), make up a large proportion of prevalent infections.2 PWUD are largely excluded from receiving HCV care, in part due to provider concerns regarding adherence and therefore treatment efficacy in this population.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) has outlined goals for the elimination of HCV as a public health concern by 2030.4 To achieve this, attention must be paid to these vulnerable populations. This analysis was conducted to document the efficacy of the three most-prescribed all-oral HCV treatment regimens in Canada (elbasvir/grazoprevir [EG], sofosbuvir/ledipasvir [SL], and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir [SV]) among a large population of PWUD, to further support campaigns for the diagnosis and treatment of HCV infection in this priority population.

METHODS

The study was a retrospective analysis of all HCV-infected PWUD (positive urine drug screen <6 months) initiating HCV treatment at our centre between June 2015 and February 2019. All subjects were enrolled in a multidisciplinary model of care, addressing medical, psychologic, social, and addiction-related needs. The primary outcome was achievement of sustained virological response 12 weeks after treatment (SVR12) (i.e., undetectable HCV RNA ≥12 weeks after the completion of HCV therapy).

RESULTS

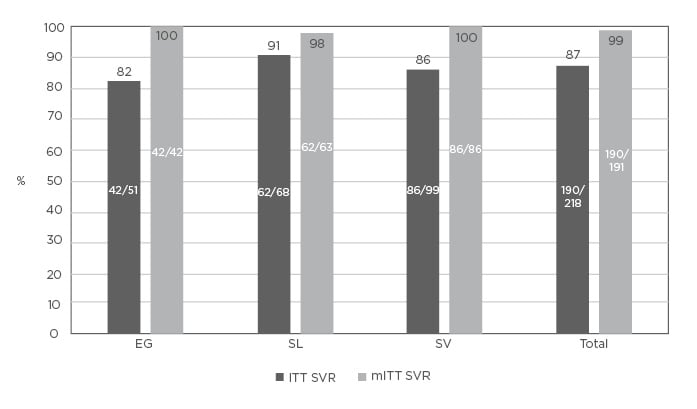

A total of 265 individuals initiated therapy with one of the regimens of interest, 218 of whom had reached sufficient follow-up for SVR12 analysis. In the EG cohort (n=61), 11% were HIV positive, 57% were on opiate substitution therapy (OST), and 3% were cirrhotic. In the SL cohort (n=74), 16% were HIV positive, 31% were on OST, and 20% were cirrhotic. Finally, in the SV cohort (n=130), 12% were HIV positive, 58% were on OST, and 17% were cirrhotic. Of those eligible for intention-to-treat SVR analysis to date, SVR12 rates are EG: 82% (42/51), SL: 91% (62/68), and SV: 87% (86/99). There was one virologic failure (in the SL group) and two deaths (one in each of the EG and SL groups); both deaths were related to opioid overdose. A total of 25/218 (11.5%) did not present for SVR12 evaluation. All are still alive, and active processes are underway to ascertain the outcome of HCV therapy and to re-engage them in long-term care. Thus, when excluding losses to follow-up and deaths (modified ITT analysis), SVR rates are EG: 100% (42/42), SL: 98% (62/63), and SV: 100% (86/86). These results can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Hepatitis C virus treatment outcomes.

EG: elbasvir/grazoprevir; ITT: intention-to-treat; mITT: modified intention-to-treat; SL: sofosbuvir/ledipasvir; SV: sofosbuvir/velpatasvir; SVR: sustained virologic response.

CONCLUSION

The authors found that the currently available regimens for the treatment of HCV appear to be highly successful among PWUD populations in this multidisciplinary care setting. Virologic failure has only been documented in one case, attesting to the efficacy of the therapeutic options, as well as the robust nature of the model of care during therapy. This might include, as needed on an individual basis, the daily dispensing of HCV medications with OST, weekly delivery of pills to shelters, and other strategies to enhance adherence. Despite these measures, about 10% of the cohort was ‘lost to follow-up’ with respect to SVR12 determination. This is not only important to ascertain outcome (although 17/25 were HCV RNA negative at last measure, including 9 at 1–11 weeks after the end of therapy), but also for long-term follow-up among cirrhotic patients and those at risk of reinfection. Going forward, the authors plan to enhance their model of care to address this important issue. These results support provision of HCV treatment to PWUD for the achievement of the WHO’s global elimination targets.