BACKGROUND

As persons with HIV (PWH) age, non-AIDS-defining cancers (NADC) are emerging as a leading cause of morbidity and mortality.1 Simultaneously, BMI among PWH is increasing, with a growing proportion of individuals being categorized as overweight or obese at the time of ART initiation and while on ART.2,3 Breast cancer (BC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) are the most common obesity-related cancers among females and males, respectively, and have increased cancer-specific mortality in PWH compared to individuals without HIV.4,5 Strategies to optimize screening practices for early detection while maintaining equitable access is essential in managing the care of this aging population. With healthcare digitalization, evolving HIV care models, and anticipated AI integration, the authors investigated BC and CRC screening rates, along with individual and system-level factors associated with screening completion.

METHODS

This single center, retrospective cohort study took place between 1 July 2022–1 July 2023, among PWH aged 40–75 years at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Infectious Diseases Clinic (OSUWMC IDC), Columbus, Ohio. Established PWH (≥3 appointments between 1 July 2020–1 July 2023 with ≥1 within the study period) were included. The primary outcome was ordering and completion of BC and CRC screenings based on the United States Preventative Services Taskforce guidelines. Demographics were summarized as frequencies and percentages across groups with different screening status. Associations between factors and outcomes were assessed using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Descriptive statistics and p values were considered for evaluating associations between characteristics and screening status.

RESULTS

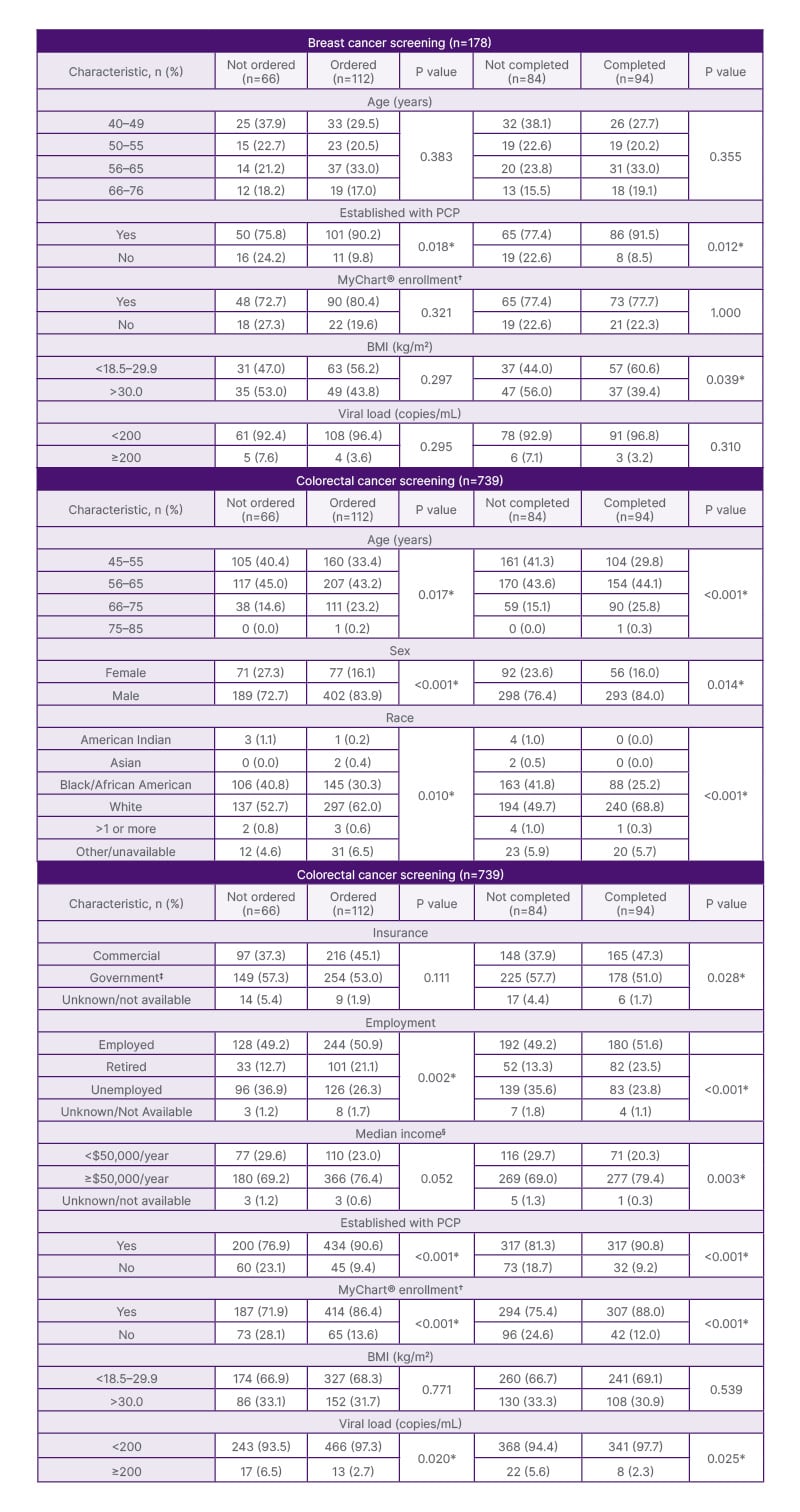

A total of 178 PWH were eligible for BC screening. Of these, 62.9% (112/178) had BC screening ordered and 52.8% (94/178) had BC screening completed. One hundred and thirteen (63.5%) were of Black or African American race, 151 (84.8%) had a primary care physician (PCP), and 138 (77.5%) were enrolled in an electronic medical record application (MyChart®, Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, Wisconsin). There was a statistically significant association between having a PCP (90.2% versus 75.8%; p=0.018) and ordering of BC screening. Additionally, PWH who completed BC screening were less likely to have obesity (39.4% versus 56.0%; p=0.039) and were more likely to be established with a PCP (91.5% versus 77.4%; p=0.012).

Of those enrolled, 739 PWH were eligible for CRC screening, of whom 64.8% (479/739) had CRC screening ordered and 47.2% (349/739) had CRC screening completed. Five hundred and ninety-one (80.0%) were assigned male at birth, 634 (85.8%) had a PCP, and 601 (81.3%) were enrolled in MyChart. Significant associations were observed between having a PCP (90.8% versus 81.3%; p<0.001), higher median income (79.6% versus 69.9%; p=0.003), and MyChart enrolment (88.0% versus 75.4%; p<0.001) and CRC screening completion. Other notable variables are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Notable characteristics by differing screening status for breast and colorectal cancer.

*p<0.05 is considered significant.

†MyChart® is an electronic medical record application.

‡Government insurance represents: Medicare, Medicaid, and Ryan White coverage.

§Median income was estimated by zip code.

PCP: primary care provider.

CONCLUSION

Improving BC and CRC screening rates is essential for reducing morbidity, mortality, and disparities of these cancers among PWH. The authors’ study highlights opportunities for large-scale integration of electronic interventions to improve screening rates. It also identifies marginalized populations that may benefit from additional resource allocation and targeted interventions to ensure equitable access and delivery of preventative care services. This framework may be considered for expansion to other preventative care measures to improve overall health of aging PWH.