INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) care among women experiencing incarceration is rarely addressed in the literature. Although women comprise a minority of persons experiencing incarceration in the USA,1 studies have shown higher HCV seroprevalence among women in this population compared with men.2-4 In the New York City (NYC) jail system, women make up 7% of the population but represent 18% of individuals diagnosed with active HCV. This study describes the HCV care cascade for women and men in the NYC jail system and examines potential gender-related factors in outcomes.

METHODS

Persons admitted to the NYC jail system and who completed a medical intake between October 2019–December 2023 were included in this retrospective cohort analysis.

The authors constructed a care cascade including:

1. HCV screening (HCV rapid test through universal opt-out testing, HCV RNA or genotype test, or HCV self-report)

2. Confirmatory HCV testing (HCV RNA or genotype test)

3. Diagnosis (detectable confirmatory test result)

4. Linkage to jail-based clinical HCV care

5. Jail-based HCV treatment initiation

6. On-site completion of HCV treatment

7. On-site SVR12 test ≥64 days after treatment completion

8. On-site undetectable SVR12 test

Descriptive statistics, Chi-Square analysis, and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to examine differences between men and women in demographic characteristics, medical history, and rates of progress through the HCV care cascade.

RESULTS

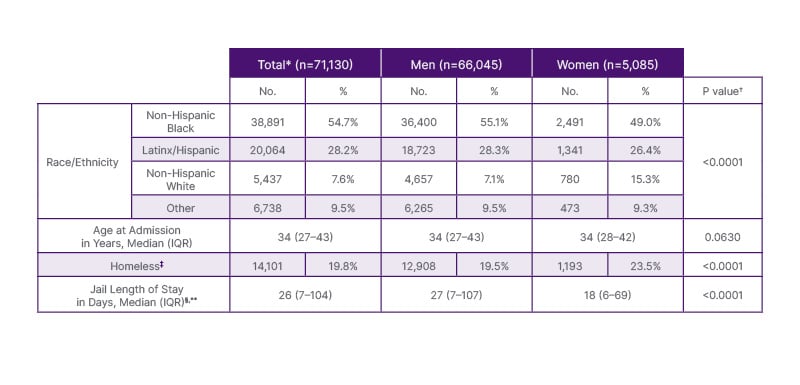

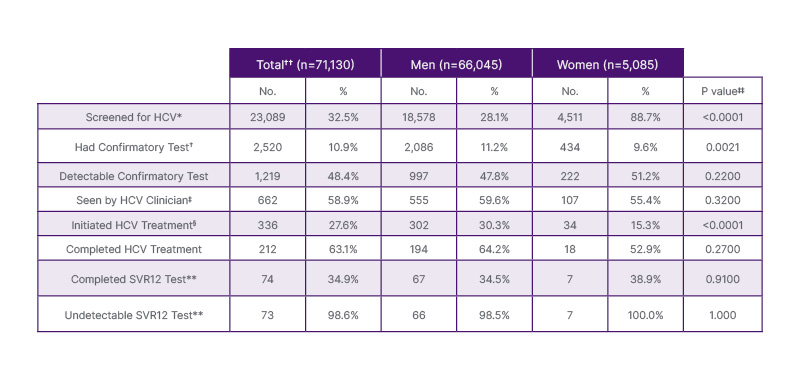

The study included 71,130 people, and 5,085 (7.1%) were women (Table 1). Compared to men, women had higher rates of screening (88.7% versus 28.1%; p<0.0001) and lower rates of confirmatory testing (9.6% versus 11.2%; p=0.002) (Table 2). Both groups had similar rates of active HCV (51.2% versus 47.8%; p=0.22) and linkage to on-site HCV care (55.4% versus 59.6%; p=0.32).

Table 1: Population demographics, stratified by documented gender.

*Analysis is at the incarceration, not person level.

† Chi-Square testing was used for categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney U testing was used for continuous variables. Comparison was between gender groups.

‡Patient indicated being homeless prior to incarceration through self-report during medical intake.

§Each date was counted as a separate day.

**Does not include individuals currently incarcerated with no discharge date (n=3734).

No: number; IQR: interquartile range.

Table 2: Hepatitis C care cascade outcomes, stratified by documented gender.

Percentages for each step were based on prior step, except where otherwise noted.

*HCV screening was defined as having an HCV antibody, RNA, or genotype test, or self-reporting HCV.

†HCV confirmatory test was defined as having an HCV RNA or genotype test.

‡Among patients with a length of stay ≥6 days.

§Percentage was based on patients with a detectable confirmatory test.

**SVR12 tests to confirm cure were defined as an HCV RNA test ≥64 days and ≤6 months after treatment completion.

††Analysis is at the incarceration, not person level.

‡‡Chi-square testing was used for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U testing was used for continuous variables.

The comparison was between gender groups.

Women initiated HCV treatment at nearly half the rate of men (15.3% versus 30.3%; p<0.0001). Women and men completed HCV treatment, SVR12 testing, and on-site cure confirmation at similar rates.

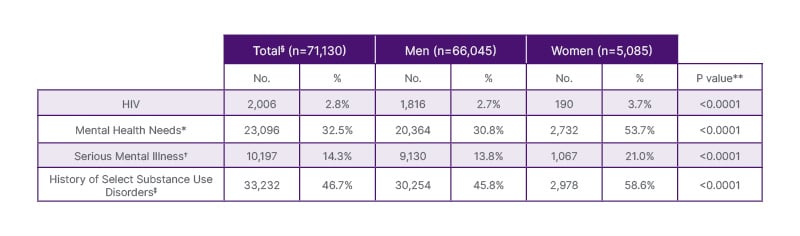

Women in the NYC jails had significantly higher rates of homelessness (23.5% versus 19.5%), HIV (3.7% versus 2.7%), mental health needs (53.7% versus 30.8%), and history of select substance use disorders (58.6% versus 45.8%) when compared to men (p<0.0001) (Table 3). Women had significantly shorter median length of stay in jail than men (18 days versus 27 days; p<0.0001).

Table 3: Population health characteristics, stratified by documented gender.

*Patient was enrolled in mental health services during incarceration.

†Patient has serious mental illness diagnosis during incarceration. CHS defines SMI to include (a) schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, (b) bipolar and related disorders, (c) depressive disorders, or (d) post-traumatic stress disorder, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5), or individuals who do not meet the above diagnostic criteria but experience severe functional impairment or clinical distress as a result of a DSM-5 diagnosis. These exclude diagnoses resulting from substance use or medical condition.

‡Defined as any one or multiple of alcohol use disorder, opioid use disorder, and cocaine use disorder.

§Analysis is at the incarceration, not personal, level.

**Chi-square testing was used for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U testing was used for continuous variables. The comparison was between gender groups.

CONCLUSION

Large HCV treatment gaps exist between women and men experiencing incarceration. Disproportionally higher rates of medical, mental health, and history of substance use disorders, as well as shorter lengths of stay, are associated with treatment differences among women. Further work is needed to elucidate the individual impacts of these factors on HCV care outcomes among women.

Gender-specific strategies centered on the needs of women with justice involvement are required to improve the uptake of jail-based HCV treatment. In light of notably short lengths of stay in municipal jail systems, optimizing treatment access for all persons with justice involvement is critical for HCV elimination efforts